Defining "Retirement" for Tax Purposes: The Japanese Supreme Court's 10-Year Retirement Allowance Case

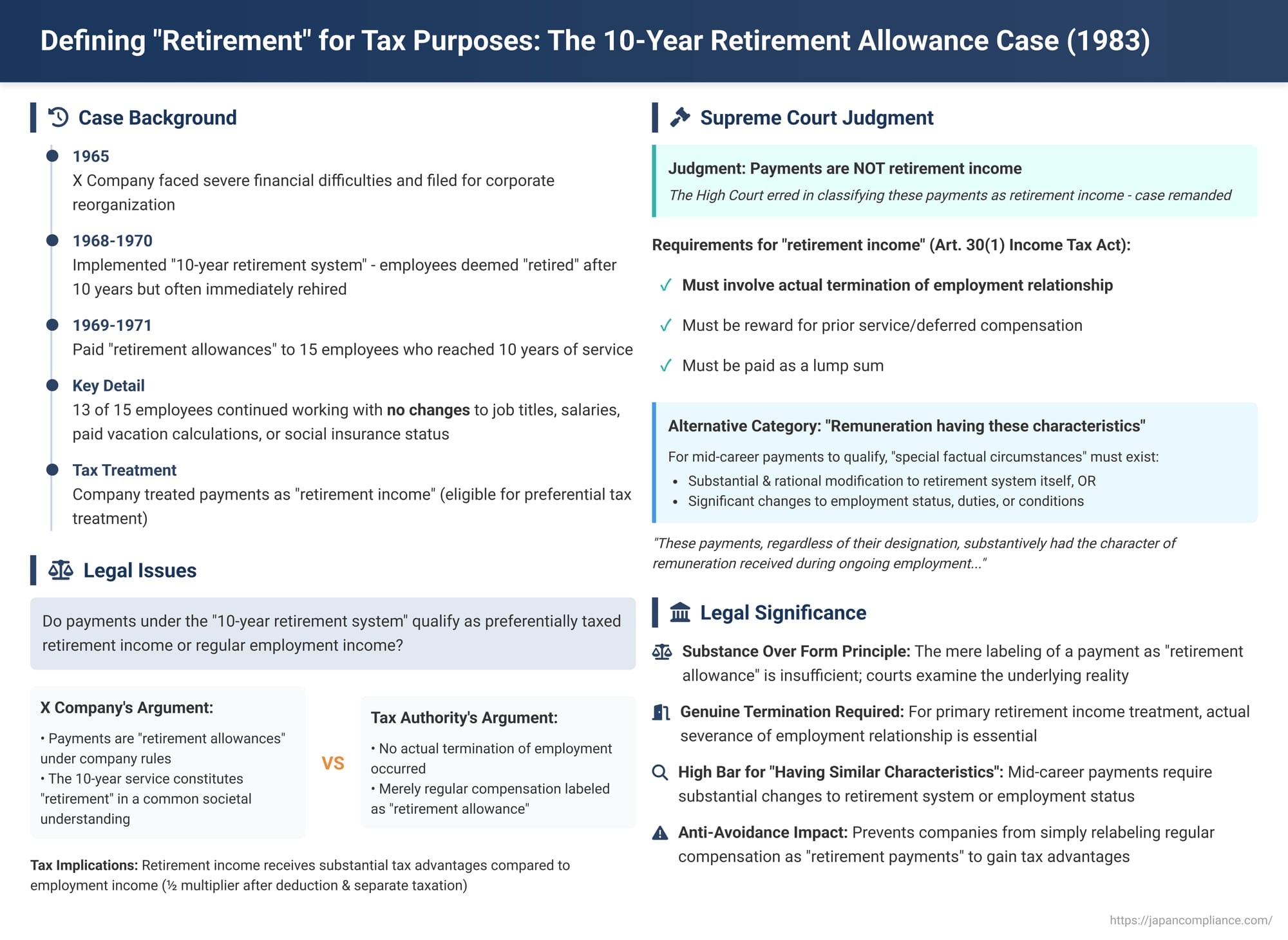

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of December 6, 1983 (Showa 54 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 35: Action for Rescission of Withholding Tax Payment Obligation Notice, etc.) – Commonly known as the "10-Year Retirement Allowance Case"

Introduction

On December 6, 1983, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a crucial judgment that clarified the definition of "retirement income" (退職所得, taishoku shotoku) for Japanese income tax purposes. This case, known as the "10-Year Retirement Allowance Case" (10年退職金事件), examined whether payments made to employees by X Company under a newly instituted "10-year retirement system" – where employees were nominally retired after ten years of service but often immediately re-employed without significant changes to their working conditions – qualified for the preferential tax treatment afforded to retirement income, or if they should be taxed as regular employment income (給与所得, kyūyo shotoku). The Supreme Court's decision delved into the substance of what constitutes "retirement" and set forth stringent criteria for classifying payments as genuine retirement income.

The core issue revolved around the interpretation of Article 30, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act, which defines retirement income and distinguishes it from other forms of compensation. The ruling emphasized that for a payment to be considered retirement income, it must genuinely arise from the termination of an employment relationship or possess characteristics substantively equivalent to such a payment due to special circumstances.

Facts of the Case

X Company (the appellee), which had previously implemented a mandatory retirement age of 55 for its employees, began experiencing severe financial difficulties around 1965. The company accumulated substantial debt and, in September of that year, filed for corporate reorganization under Japan's Corporate Reorganization Act. In this precarious situation, the company's employees proposed a change to the retirement system: they suggested that reaching 10 years of continuous service should be considered retirement, at which point a retirement allowance would be paid. If employees wished to continue working thereafter, they would be formally "re-employed." X Company also found this proposal potentially beneficial, as it could alleviate the burden of higher salaries for long-serving, older employees.

Following this alignment of interests, X Company decided to implement the 10-year service retirement system. This was first incorporated into its Retirement Allowance Regulations in October 1968. Subsequently, in November 1970, the company's Work Rules were amended. Article 28 of the revised Work Rules stipulated: "The retirement age for employees shall be 55 years of age, or upon completion of 10 full years of continuous service. However, even if an employee reaches retirement age, the company may, if there is an operational necessity, newly employ the individual after considering their ability, performance, health condition, etc."

Between March 1969 and November 1971, X Company paid "retirement allowances" to 15 employees who had reached 10 years of continuous service, as per the new Retirement Allowance Regulations. The company treated these payments as retirement income for the purpose of withholding income tax. Of the 15 employees who received these payments, two retired shortly thereafter. However, the remaining 13 employees continued to work for X Company. For these continuing employees, there were no changes to their job titles, salary levels, the method of calculating their paid vacation days, or their social insurance status (i.e., no switch indicating a termination and re-hire).

Y, the director of the competent tax office (the appellant), determined that these "retirement allowances" actually constituted employment income under the Income Tax Act, not retirement income. Consequently, Y issued a withholding tax payment obligation notice and a non-payment penalty assessment against X Company. X Company contested these dispositions. After its objections and administrative appeals were dismissed, X Company filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the tax authority's actions.

The Osaka District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled in favor of X Company. It held that "retirement based on X Company's 10-year continuous service retirement system should be recognized as having the character of retirement in common societal understanding, regardless of subsequent re-employment." Thus, the payments were deemed retirement income. The Osaka High Court upheld this decision, dismissing the tax authority's appeal. Y, representing the tax authority, then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the judgment of the High Court and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court provided a detailed exposition of the legislative intent behind the preferential tax treatment for retirement income and established specific criteria for classifying payments under Article 30, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act.

Legislative Intent of Preferential Tax Treatment for Retirement Income

The Court began by explaining the rationale for the special tax treatment afforded to retirement income, which is defined in Article 30, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act as income pertaining to "retirement allowance, lump-sum pension, other remuneration received at one time due to retirement, and remuneration having these characteristics."

- This preferential treatment exists because lump-sum payments made at the time of retirement, regardless of their specific name (e.g., retirement allowance, severance pay), generally possess two key characteristics:

- Nature/Content: They serve as (a) a reward for the retiree's long-term service to a particular employer or entity, and (b) an accumulation of a portion of the compensation for labor provided during that period (i.e., deferred wages).

- Function: They function to (c) provide for the recipient's livelihood after retirement, often serving as the primary means of support during old age.

- The Court reasoned that taxing such lump-sum payments uniformly with other types of general employment income, using progressive tax rates that would apply to the entire amount at once, would lead to unfairness and produce socially undesirable outcomes from a policy perspective. The preferential measures for retirement income are intended to avoid such consequences.

- Therefore, whether a payment made to an employee upon retirement qualifies as retirement income under the Income Tax Act must be determined not merely by its name, but by reference to the literal wording of Article 30, Paragraph 1, and the aforementioned legislative intent.

Requirements for "Remuneration Received at One Time Due to Retirement"

Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court laid out three essential requirements for a payment to qualify as "retirement allowance, lump-sum pension, other remuneration received at one time due to retirement" under Article 30, Paragraph 1:

- The payment must be made for the first time due to the fact of "retirement," meaning the termination of the employment relationship.

- The payment must have the nature of a reward for previous continuous service or a deferred payment of a portion of the remuneration for labor during that service period.

- The payment must be made as a lump sum.

Requirements for "Remuneration Having These Characteristics"

Article 30, Paragraph 1 also includes "remuneration having these characteristics" within the definition of retirement income. For this category, the Court stated:

- Even if a payment does not formally satisfy all three of the above requirements, it must substantively conform to what these requirements demand and be such that it is appropriate to treat it, for tax purposes, in the same manner as "remuneration received at one time due to retirement".

Application to the Facts – Regarding "Termination of Employment"

The Supreme Court then applied these criteria to the facts of X Company's case:

- The Court found that, based on the facts established by the High Court, it could not immediately be concluded that the employees who received the payments termed "retirement allowances" had actually retired upon reaching 10 years of service and that their employment relationship with X Company had terminated at that point.

- The Court noted that while the 10-year retirement system was adopted due to the concurring opinions of both labor and management and not for tax avoidance purposes, the direct motivation for employees was primarily to secure a retirement payout given the company's financial instability, rather than an expectation of actual retirement. For many, continued employment was anticipated. The company, too, seemed to have implemented the system mainly as a mechanism to pay out these sums, intending for employment to continue for most.

- The fact that the majority of those who received the payment continued to work without any change in their job roles, salaries, paid leave calculations, or social insurance status strongly indicated a continuity of employment.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that these payments, regardless of their designation, substantively had the character of remuneration received during ongoing employment. They lacked the first essential requirement for primary retirement income: being a payment triggered by the fact of retirement, i.e., the termination of the employment relationship.

Application to the Facts – Regarding "Remuneration Having These Characteristics"

Next, the Supreme Court considered whether these mid-career payments, though not meeting the primary definition, could qualify as "remuneration having these characteristics":

- For a payment made during the course of continuous employment (even if called a retirement allowance) to substantively meet the requirements of the three criteria and be treated identically to "remuneration received at one time due to retirement," certain special factual circumstances must exist.

- The Court provided examples of such special circumstances:

- The payment is made due to the necessity of a financial settlement arising from a substantial and rational modification of the retirement allowance payment system itself, such as extending the formal retirement age or adopting a new retirement pension scheme.

- There are significant changes in the nature, content, or working conditions of the employment relationship, such that the formally continuing employment cannot be regarded as a mere extension of the previous employment relationship.

- The Supreme Court found that the facts established by the High Court in X Company's case did not demonstrate the existence of such special circumstances that would justify classifying the disputed payments as "remuneration having the nature of remuneration received at one time due to retirement".

The Court concluded that the High Court erred in its interpretation and application of the law and had failed to conduct a sufficient examination of the facts. Therefore, the High Court's judgment was overturned, and the case was remanded for further proceedings.

Commentary Insights

This 1983 Supreme Court decision, often discussed alongside the similar "5-Year Retirement Allowance Case" (Supreme Court judgment, September 9, 1983), provides critical guidance on distinguishing retirement income from employment income.

The Core Problem: Distinguishing Employment and Retirement Income

The central issue in this case was the classification of payments made under X Company's 10-year service retirement system. As the commentary notes, the Income Tax Act provides various tax burden reduction measures for retirement income due to its special characteristics. These include applying a 1/2 multiplier to the income amount after deducting a substantial retirement income allowance (though this 1/2 multiplier has been restricted for certain high-income, short-service executives since 2012 and further for other short-service employees for amounts over 3 million yen since 2021), and applying progressive tax rates separately from other income.

However, both employment income and retirement income fundamentally arise as consideration for labor or services within an employment or similar relationship. Their qualitative nature is similar; the main difference lies in the timing and mode of payment – employment income is typically paid periodically during ongoing employment, while retirement income is paid as a lump sum upon termination of employment. This makes the distinction difficult in borderline cases like the present one.

Requirements for "Remuneration Received at One Time Due to Retirement"

The Supreme Court, in this judgment, explicitly derived the three conditions for a payment to be "remuneration received at one time due to retirement" (termination of employment, nature as reward/deferred pay, lump-sum payment) from the legislative intent behind the preferential tax treatment of retirement income. As mentioned, these aims are recognizing retirement payments as a reward for long service and accumulated deferred compensation, and acknowledging their function in securing post-retirement livelihood. This portion of the ruling directly quoted the Supreme Court's earlier decision in the "5-Year Retirement Allowance Case".

Regarding the first condition, "retirement" (termination of employment), there are differing academic views. The dominant theory considers "retirement" a unique tax law concept signifying a departure from previous employment. An alternative view treats it as a borrowed concept from private law, equating it with the termination of the employment contract. The former interpretation allows for consideration of broader circumstances, such as the purpose of the retirement allowance payment and changes in working conditions, while the latter focuses more narrowly on the legal status of the employment contract (though still emphasizing substance over mere form).

Requirements for "Remuneration Having These Characteristics"

Retirement income under Article 30, Paragraph 1 also encompasses "remuneration having these characteristics," not just payments strictly meeting the primary definition. The Supreme Court, again following the "5-Year Retirement Allowance Case," stated that even if a payment doesn't fulfill all three formal requirements, it can still qualify if it substantively aligns with what those requirements demand.

There is academic debate on the scope of this secondary category. The majority view, which this Supreme Court ruling appears to align with, interprets this category narrowly and still generally requires a factual basis of retirement or something very close to it. An alternative view argues that if a payment has the same economic substance as a normal retirement allowance, the actual fact of formal retirement is not indispensable. A dissenting opinion by Justice Yokoi in this very case leaned towards this latter interpretation, highlighting changes in Japan's traditional lifetime employment system and emphasizing the reward aspect of such payments.

This Supreme Court judgment notably elaborated on the "special factual circumstances" required for a mid-career payment to qualify under this secondary category, citing examples such as a substantial modification of the retirement allowance system or significant changes in employment conditions. It's noted that tax administration practice (e.g., Income Tax Basic Directives 30-2 and 30-2-2) also allows for retirement income treatment under certain conditions in these specific scenarios.

Context of the "10-Year" and "5-Year" Retirement Allowance Cases

Both this case and the "5-Year Retirement Allowance Case" involved situations where companies adopted schemes to pay out "retirement allowances" at 5 or 10-year intervals, often with formal "re-employment" but without significant alterations to the employees' actual working conditions. These were effectively methods of pre-paying retirement benefits. In such scenarios, the primary legal question was whether a genuine retirement (termination of employment) had occurred, making the applicability of the primary definition of "remuneration received at one time due to retirement" the main point of contention.

In contrast, the commentary points to more recent court cases that focus on the secondary category – "remuneration having these characteristics" – where an employee continues with the same company, but a payment is triggered by significant changes in their duties or employment conditions. Several lower court decisions have classified such payments as retirement income where substantial changes were found. Examples include:

- A school director retiring as head of junior and senior high schools to become president of the university run by the same educational institution (Osaka District Court, February 29, 2008).

- A company employee becoming an executive officer of the same company and receiving a retirement payment for their period as an employee (Osaka High Court, September 10, 2008).

- A director of an educational institution who also served as principal of one of its schools receiving a retirement payment upon relinquishing these specific roles (Kyoto District Court, April 14, 2011).

These cases indicate a judicial willingness to recognize payments as retirement income when there is a substantive change in employment status or role, even without a complete severance from the employing entity.

Broader Implications and Discussion

The Supreme Court's 1983 decision carries several broader implications:

- Substance Over Form: The ruling strongly affirms the principle of "substance over form" in tax law. The mere labeling of a payment as a "retirement allowance" is insufficient; its true nature, determined by the surrounding facts and circumstances, is paramount.

- Genuine Termination Required: For a payment to qualify as retirement income in its primary sense, a genuine termination of the employment relationship is essential. Schemes that involve nominal retirement followed by immediate re-employment without substantive changes to work conditions are unlikely to meet this criterion.

- Narrow Scope for "Having the Nature Of" Retirement Income: The Court established a high bar for mid-career payments to be treated as "remuneration having these characteristics." Such classification requires proof of "special factual circumstances," such as a fundamental and rational overhaul of the retirement system or a truly significant transformation in the employee's working conditions or status, making the ongoing employment substantively different.

- Challenges for Employers: This decision poses challenges for employers wishing to design flexible compensation or early payout schemes. Simply calling a payment a "retirement allowance" will not secure preferential tax treatment for employees if the underlying conditions of genuine retirement or qualifying special circumstances are not met.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary prompt further reflection on the relationship between the legislative aims of retirement income preference and specific tax relief measures, the alignment of the three formal requirements with these legislative aims, and the precise distinctions between "remuneration received at one time due to retirement" and "remuneration having these characteristics". These questions highlight the ongoing need to interpret these provisions in light of evolving employment practices.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 6, 1983, judgment in the "10-Year Retirement Allowance Case" significantly clarified the criteria for classifying payments as retirement income under Japanese tax law. By emphasizing the necessity of an actual termination of the employment relationship for the primary definition of retirement income, and by strictly defining the "special factual circumstances" required for mid-career payments to be treated as having the nature of retirement income, the Court reinforced a substance-based approach to income classification. This ruling underscores the difficulty of obtaining preferential tax treatment for payments that are effectively made during an ongoing employment relationship without a genuine severance or a profound, objectively justifiable change in the employment framework or retirement system.