Defining Responsibility: The Duty of Explanation in Japanese Team-Based Medical Care – A Supreme Court Perspective

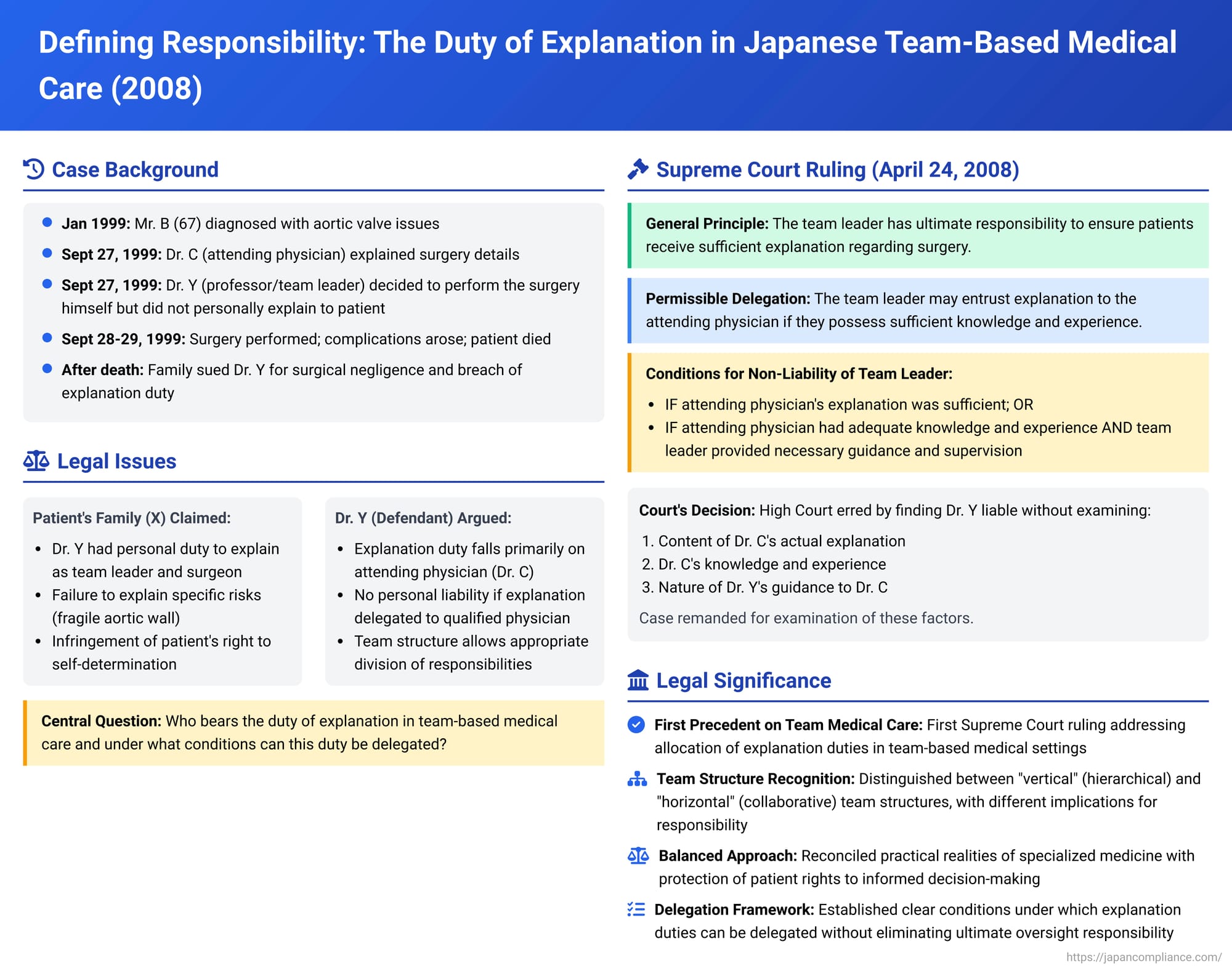

Date of Judgment: April 24, 2008, Supreme Court of Japan (First Petty Bench)

In the increasingly specialized and collaborative environment of modern medicine, "team-based care" has become a cornerstone of patient treatment. While this approach offers numerous benefits by pooling diverse expertise, it can also complicate lines of responsibility, particularly concerning the crucial duty of providing patients with adequate information to make informed decisions about their medical care—often referred to as informed consent. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 24, 2008, delved into these complexities, specifically addressing how the duty of explanation is allocated within a medical team and the extent of the team leader's personal responsibility.

The Case: A Fatal Heart Surgery and Questions of Responsibility

The case concerned Mr. B, a 67-year-old man, who was diagnosed in January 1999 with aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation, requiring aortic valve replacement surgery. In September 1999, he was admitted to the cardiac surgery department of A University Hospital for this procedure.

At A University Hospital, Dr. C, an assistant professor (hospital lecturer) in cardiac surgery, was assigned as Mr. B's attending physician (主治医 - shujii). On September 27, 1999, Dr. C met with Mr. B and his family (his wife X1, and children X2 and X3, collectively referred to as X) to explain the necessity of the surgery scheduled for the next day, its details, and the associated risks.

Dr. Y was a professor in the same cardiac surgery department at A University and was the overall supervising physician for Mr. B's surgical team. Initially, another doctor, Dr. D, was slated to be the lead surgeon. However, on the afternoon of September 27, Dr. Y informed Dr. C that he (Dr. Y) would personally perform the surgery as the lead surgeon. Dr. Y himself never directly provided any explanation about the surgery to Mr. B or his family, X.

The surgery commenced on September 28, 1999. Dr. C initially began the operation, but after extracorporeal circulation (heart-lung machine) was initiated, Dr. Y took over as the lead surgeon, with Dr. C and Dr. D assisting. During the procedure, it was found that Mr. B's aortic wall was unusually thin and fragile. After the artificial valve was sutured and the aortic wall was closed, bleeding occurred from the suture sites as blood pressure was gradually increased. Despite repeated efforts and additional sutures, the bleeding persisted. Dr. Y left the operating room around 3:00 PM after the bleeding appeared to have stopped. Later, Dr. D and another doctor, E, continued the surgery. Around 5:00 PM, Dr. C briefly left the OR to update X, explaining that Mr. B's blood vessels were more fragile than expected, causing persistent bleeding from the suture lines. An aortic patch was eventually sutured in. However, difficulties arose in weaning Mr. B from the heart-lung machine. Dr. Y was called back to the OR around 9:20 PM. Mr. B was suspected of suffering a myocardial infarction due to right coronary artery occlusion, necessitating a coronary artery bypass graft, which was started around 10:36 PM by Dr. E and others. Dr. Y left the operating room at this point.

Despite these interventions, Mr. B was unable to overcome circulatory failure after being weaned off the heart-lung machine and passed away on September 29, 1999.

Mr. B's heirs, X, filed a lawsuit against Dr. Y, alleging both surgical negligence and a breach of the duty of explanation regarding the surgery, seeking damages based on tort.

The Legal Journey: Lower Courts and Diverging Views

- District Court (Osaka District Court, Sakai Branch): The trial court rejected all of X's claims. It found no evidence of surgical negligence on the part of Dr. Y and also concluded that there was no breach of the duty of explanation.

- High Court (Osaka High Court): X appealed to the Osaka High Court. The High Court also denied the existence of surgical negligence. However, it found Dr. Y liable for a breach of the duty of explanation.

The High Court reasoned that Dr. Y, as the overall head of the medical team and the one who ultimately performed the surgery, had a duty to explain to Mr. B and his family, X, that Mr. B's severe aortic regurgitation and other factors (age, hypertension, enlarged aorta visible on pre-operative imaging) indicated a significant possibility of a fragile aortic wall. This fragility, in turn, meant there was a risk of severe bleeding during the surgery, potentially leading to a critical situation, including the need for bypass surgery. Since Dr. Y admittedly never provided such specific explanations himself, the High Court concluded he had violated his duty of explanation under the principle of good faith and trust. It awarded X damages for the infringement of Mr. B's right to self-determination (i.e., the right to make an informed choice about his treatment).

Dr. Y then appealed this part of the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the duty of explanation in this team medical care setting should primarily be the responsibility of Dr. C, the attending physician.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling (April 24, 2008)

The First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision regarding Dr. Y's liability for breach of the duty of explanation and remanded the case back to the Osaka High Court for further proceedings.

The Supreme Court laid out general principles concerning the duty of explanation in the context of team-based medical surgery:

- Overarching Responsibility of the Team Leader: As a matter of general principle derived from natural justice (jōri), the chief or overall leader of a medical team performing surgery has a duty to ensure that the patient and/or their family receive a sufficient explanation regarding the necessity of the surgery, its contents, associated risks, and other relevant factors.

- Permissibility of Delegation: However, this does not mean the team leader must always provide this explanation personally. If the attending physician, who has been involved in the patient's care leading up to the surgery, possesses sufficient knowledge and experience to provide the necessary explanations, the team leader is permitted to entrust this task to the attending physician. In such cases, the team leader's role may be limited to guiding and supervising the attending physician as necessary.

- Conditions for Non-Liability of the Team Leader:

- If the explanation provided by the attending physician is sufficient, the team leader cannot be held liable in tort for a breach of the duty of explanation merely because they did not provide the explanation themselves.

- Furthermore, even if the attending physician's explanation is found to have been insufficient, the team leader will still not be held liable for a breach of the duty of explanation if it is established that:

- The attending physician possessed sufficient knowledge and experience to give a proper explanation, AND

- The team leader provided necessary guidance and supervision to that attending physician.

- These principles apply even if the team leader is also the one who performs the surgery.

Application to Dr. Y's Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred. The High Court had held Dr. Y liable solely because he did not personally explain the specific risks associated with Mr. B's potentially fragile aortic wall. It did so without adequately examining:

- The specific content of the explanation that Dr. C (the attending physician) actually provided to Mr. B and X.

- Dr. C's knowledge and experience concerning the type of surgery and its risks.

- The nature and extent of any guidance or supervision Dr. Y provided to Dr. C regarding the explanation process.

The Supreme Court reasoned that if Dr. C's explanation was indeed sufficient, Dr. Y would not be liable. Even if Dr. C's explanation was insufficient, Dr. Y would still not be liable if Dr. C was adequately qualified (in terms of knowledge and experience) and Dr. Y had fulfilled his supervisory duties. Because the High Court failed to deliberate on these crucial factual elements, its judgment was flawed. The case was therefore sent back to the High Court for a re-examination of these points.

Understanding "Team Medical Care" and Its Implications for Explanation Duties

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision was significant as it was the Court's first explicit ruling on the allocation of the duty of explanation within what it termed "team medical care" (チーム医療 - chīmu iryō). This term itself is broad and can encompass various collaborative structures in healthcare.

Commentary surrounding this judgment suggests that "team medical care" can manifest in different forms, which can influence how responsibilities, including the duty of explanation, are distributed:

- "Vertical" Team Care (Hierarchical Structure): This model aligns with the circumstances of the Supreme Court case. It typically involves a team of medical professionals within a single specialized department (like cardiac surgery in a university hospital) operating under a clear hierarchy. The team leader (often a senior professor like Dr. Y) holds ultimate authority and responsibility. This structure is characterized by unity in purpose and a defined sharing of roles. The duty of explanation, while ultimately an obligation of the team overseen by its leader, is often practically delegated to the attending physician (like Dr. C) who has the most direct and ongoing contact with the patient. The team leader’s responsibility is to ensure that an adequate explanation occurs, which involves selecting competent physicians for such tasks and providing appropriate guidance and supervision. The Supreme Court's ruling implies that if the delegated physician is well-qualified and properly supervised, the leader might avoid liability even if an explanation is flawed. However, some legal commentators suggest that in such integrated "vertical" teams, where the team's actions are highly unified, it might be practically difficult for a team leader to be entirely absolved of responsibility if a patient is ultimately found to have been inadequately informed, given the leader's overarching duty of care. The leader's duty to supervise has been likened by some to an employer's vicarious liability for their employees, where complete exoneration is rare.

- "Horizontal" Team Care (Collaborative Structure): This model involves collaboration between medical professionals from different specialties who work together on a patient's care (e.g., a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, and an oncologist). This structure is often characterized by the relative independence and distinct expertise of each specialist. In such "horizontal" teams, the duty of explanation might be more nuanced. While a primary attending physician or surgeon might explain the overall treatment plan, specialists involved in specific parts of the care (like an anesthesiologist regarding anesthesia risks, or a radiologist regarding interventional radiology procedures) may have a more direct and independent duty to explain the particular risks, benefits, and alternatives related to their specific area of expertise. This is especially true if these specialized risks are not, or cannot be, adequately covered by the primary physician.

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision primarily addresses the "vertical" team model. It affirms that the team leader isn't merely a figurehead but bears a substantive responsibility to ensure the patient's right to information is upheld. The practical mechanism for this is often delegation, but this delegation must be reasonable (to a qualified individual) and accompanied by necessary oversight.

The Attending Physician's Critical Role

Regardless of the team leader's oversight responsibilities, the Supreme Court's framework implicitly underscores the paramount importance of the explanation provided by the physician who actually interacts with the patient for this purpose. In many hospital settings, and certainly in the case of Dr. C, this is the attending physician. This physician is at the frontline of patient communication. Their ability to convey complex medical information clearly, to assess the patient's understanding, and to address their concerns and questions is fundamental to the principle of informed consent. The adequacy of their knowledge, experience, and communication skills is therefore a central factual element in determining whether the overall duty of explanation owed to the patient has been met.

Practical Considerations and Unresolved Questions

The Supreme Court's decision highlights several practical considerations for hospitals and medical teams:

- Clear Internal Protocols: Medical institutions, particularly those employing team-based care models, need clear internal protocols regarding who is responsible for providing explanations, what information must be conveyed, and how this process should be documented.

- Effective Delegation and Supervision: Team leaders must be diligent in delegating the task of explanation only to colleagues who possess the requisite knowledge, experience, and communication skills. Furthermore, ongoing supervision and guidance, especially for complex cases or less experienced physicians, are crucial. This doesn't necessarily mean the leader must be present for every explanation, but they must foster a culture where comprehensive and understandable information is consistently provided.

- Specialized Information in Multi-Specialty Teams: While the 2008 ruling focused on a single-department surgical team, its principles raise questions about more complex "horizontal" collaborations. In such scenarios, it is vital to ensure that all relevant specialists contribute to the informed consent process for their respective interventions. For instance, an anesthesiologist would typically be best placed to explain the specific risks and alternatives related to anesthesia, even if the surgeon provides the overall explanation for the surgical procedure itself. Coordinated explanations, perhaps involving joint consultations in some instances, might be desirable to provide the patient with a comprehensive picture for decision-making.

Conclusion: Balancing Responsibility and Practicality in Team Medicine

The Supreme Court's April 24, 2008, judgment offers a nuanced framework for understanding the duty of explanation within team-based medical care in Japan. It reaffirms that the leader of a medical team carries an ultimate responsibility to ensure patients are adequately informed. However, it also acknowledges the practical realities of specialized medical practice by permitting delegation of the explanation task to a qualified attending physician, provided there is appropriate guidance and supervision.

The decision underscores that a determination of liability for breach of this duty cannot be made superficially based on who did or did not speak to the patient. Instead, a thorough factual inquiry is required, focusing on the content and sufficiency of the explanation actually given, the qualifications of the physician who provided it, and the nature of the supervision by the team leader. Ultimately, the ruling emphasizes the critical importance of ensuring that every patient receives comprehensive and understandable information, enabling them to make genuinely informed decisions about their medical treatment, regardless of the organizational structure of the medical team providing their care.