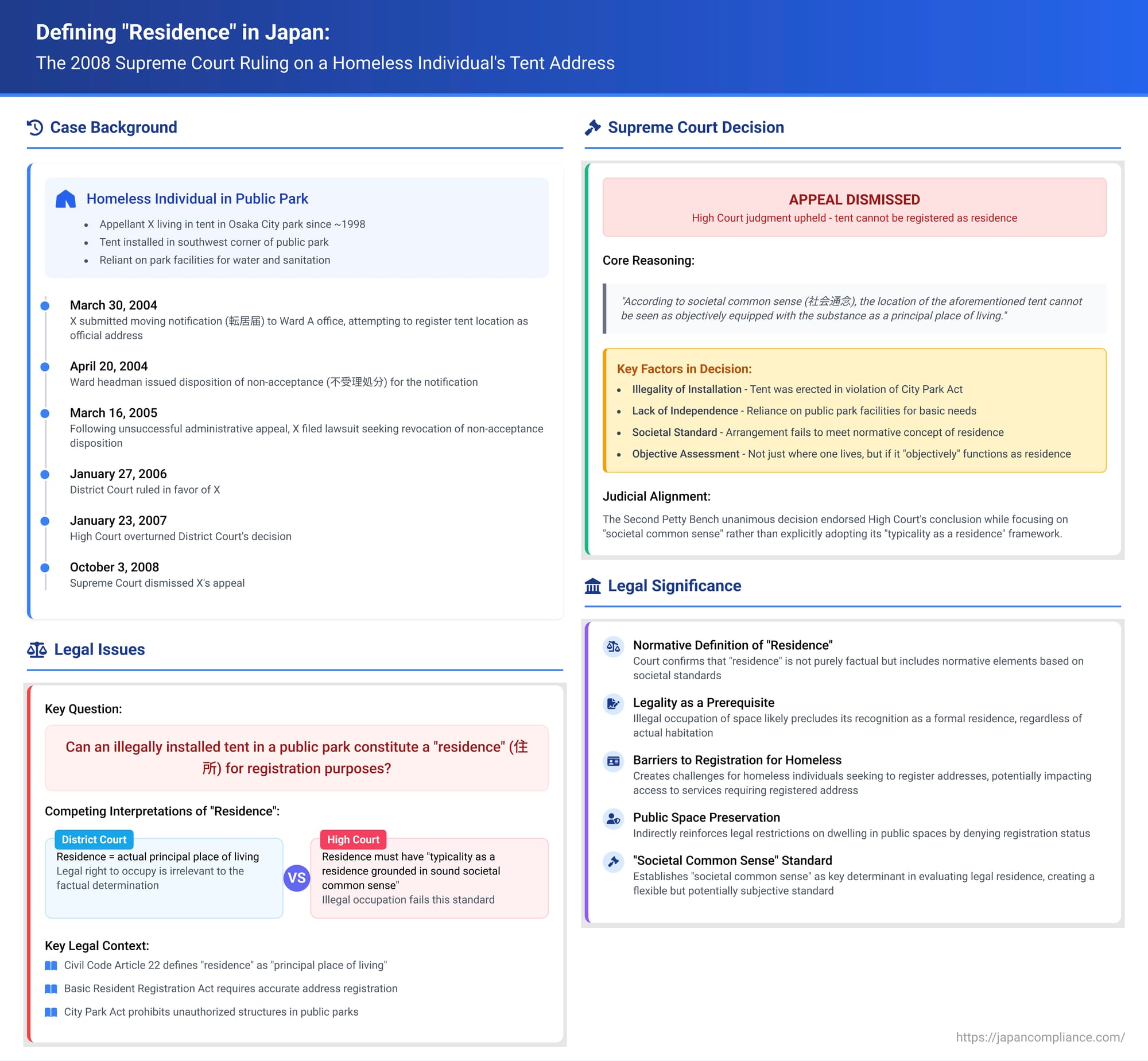

Defining "Residence" in Japan: The 2008 Supreme Court Ruling on a Homeless Individual's Attempt to Register a Park Tent as an Address

Date of Judgment: October 3, 2008

Introduction

The concept of a legal "residence" or "domicile" (住所 - jūsho) is fundamental to various aspects of legal and civic life in Japan, including resident registration, access to local government services, and voting rights. A succinct but significant judgment by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on October 3, 2008, addressed the question of whether an illegally pitched tent in a public park could be recognized as a legal residence for the purpose of a change-of-address notification under the Basic Resident Registration Act. This case, formally known as the "Action for Revocation of Disposition of Non-Acceptance of Resident Moving Notification" (Heisei 19 (Gyo-Hi) No. 137), delves into the meaning of "principal place of living" and the role of societal norms in its determination.

Background of the Dispute: Seeking Recognition of a Tent as a Home

The appellant, identified as X, had been living in a public park managed by Osaka City since approximately 1998 or 1999. From around 2000, X had been residing in a specific tent (referred to as "the tent in question") located in the southwestern corner of this park, conducting daily life there. On March 30, 2004, X submitted a moving notification (転居届 - tenkyo todoke) to the head of Ward A in Osaka City, seeking to register the location of this tent as X's official address.

However, on April 20, 2004, the ward headman issued a disposition of non-acceptance (不受理処分 - fujuri shobun) for this notification. Following an unsuccessful administrative appeal under the Administrative Complaint Review Act, X filed a lawsuit on March 16, 2005, seeking the revocation of this non-acceptance disposition.

Lower Court Decisions: A Divergence of Views

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts, reflecting the complexities in defining "residence" for individuals in unconventional living situations.

The Osaka District Court (Court of First Instance), in its judgment on January 27, 2006, ruled in favor of X. The District Court reasoned that "residence" refers to the "principal place of living" of each individual (citing Article 22 of the Civil Code). It found no specific reason to interpret "residence" under Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act differently. Thus, it defined "residence" as the center of a person's general daily life and overall existence. Whether a certain place constitutes a person's residence, the court stated, should be determined objectively by whether it substantively functions as such. The District Court concluded that the location of the tent in question objectively served as the substantive principal place of X's life. It also notably stated that whether the individual possesses a legal right of occupancy (占有権原 - sen'yū kengen) for that location is, in principle, irrelevant to the objective fact of it being the substantive principal place of living.

The Osaka High Court (Appellate Court), however, overturned this decision on January 23, 2007. While agreeing with the District Court's general definition of residence, the High Court introduced a crucial qualifier. It posited that for a location to be recognized as having the "substance as a principal place of living," it is not enough that daily life is simply carried on there. The form of that living arrangement must also possess a "typicality as a residence grounded in sound societal common sense" (健全な社会通念に基礎付けられた住所としての定型性 - kenzen na shakai tsūnen ni kisotzsuita jūsho toshite no teikeisei).

Applying this standard, the High Court found X's situation wanting. It noted that the tent was not yet considered fixed to the land. X's daily life was described as "expedient," relying entirely on public park facilities such as water supply for drinking and washing, and toilet facilities, without independent utilities like electricity. Furthermore, the High Court emphasized that the tent, a blue tarpaulin camping tent erected for X's daily living, was placed in a city park in a manner entirely unpermitted by law (specifically, the City Park Act - 都市公園法 Toshi Kōen Hō), and thus was "not in line with our sound societal common sense." Consequently, the High Court concluded that the form of X's life in the tent could not be assessed as possessing the "typicality as a residence grounded in sound societal common sense," and therefore, it did not yet have the "substance as a principal place of living." The High Court thus accepted the ward's appeal and dismissed X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court, seeking acceptance of the appeal.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Upholding Non-Acceptance

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated October 3, 2008, chose to dismiss X's appeal. The reasoning provided was concise:

The Court began by referencing the facts as lawfully established by the High Court: X was using a camping tent, illegally installed within a city park in violation of the City Park Act, as a place of abode and was carrying on daily life by utilizing park facilities such as water systems.

Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court stated that, "according to societal common sense (社会通念 - shakai tsūnen), the location of the aforementioned tent cannot be seen as objectively equipped with the substance as a principal place of living."

Therefore, the Court concluded that it could not be said that X had a residence at the location of the tent. It affirmed the High Court's judgment that the non-acceptance disposition by the ward headman was lawful. The Supreme Court found no illegality in the original (High Court) judgment as asserted by the appellant, and thus, the appellant's arguments could not be adopted.

The decision was unanimous among the justices of the Second Petty Bench. The appellant, X, was ordered to bear the costs of the appeal.

Analysis and Implications of the Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court's 2008 ruling is significant for its interpretation of "residence" in the context of Japan's resident registration system, particularly concerning individuals in precarious or legally unauthorized living situations.

- Primacy of "Societal Common Sense": The judgment places considerable emphasis on "societal common sense" as a determinant factor in assessing whether a location objectively possesses the "substance as a principal place of living." While the Civil Code (Article 22) defines a person's domicile (residence) as their "principal place of living," the Supreme Court's application suggests that this determination is not solely based on the factual observation of daily life being conducted, but is also filtered through a normative lens of what society generally accepts or recognizes as a residence.

- Illegality of Dwelling as a Key Factor: The Court explicitly highlighted that X was living in a tent "illegally installed" in a city park "in violation of the City Park Act." This illegality appears to have been a critical element in the Court's determination that the tent could not, by societal standards, be considered a principal place of living. This contrasts with the Court of First Instance's view that the legal right to occupy a place is, in principle, irrelevant to the factual determination of it being a principal place of living. The Supreme Court's reasoning implicitly links the legality of the dwelling's presence to its potential recognition as a formal residence.

- Objective Substance vs. Form of Living: The High Court had introduced the concept of "typicality as a residence grounded in sound societal common sense," focusing on the form of living. The Supreme Court, while upholding the High Court's conclusion, framed its own reasoning more directly around the lack of "objective substance as a principal place of living" when viewed through the lens of societal common sense, heavily influenced by the illegal nature of the tent's placement and use of public facilities in an unauthorized manner.

- Implications for Homeless Individuals and Resident Registration: This judgment has direct implications for homeless individuals or those living in non-traditional or unauthorized shelters who wish to register their place of abode. By endorsing the non-acceptance of a change-of-address notification for an illegally pitched tent in a public park, the Supreme Court signaled that the resident registration system may not accommodate living arrangements that significantly deviate from societally accepted norms of housing and legality. This can create barriers for individuals in accessing services that are often tied to resident registration.

- Case-Specific Ruling?: The accompanying commentary in the provided PDF suggests that while the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's decision, it did so by focusing on the evaluation of the facts of this specific case through "societal common sense," rather than by explicitly endorsing or elaborating on the High Court's more generalized and strongly normative concept of "typicality as a residence." This might suggest that the Supreme Court aimed to confine its ruling somewhat to the specific facts, where the illegality of the structure was clear and its reliance on public park amenities was total.

- The Role of "Living Base": The nature of X's living—using a camping tent and relying on public park water facilities—was central to the court's finding that it lacked the objective substance of a "principal place of living." This implies that for a location to be recognized as a residence, it must generally possess certain basic attributes typically associated with a stable living base, which the court found lacking in an illegally pitched tent reliant on public amenities.

Conclusion

The 2008 Supreme Court decision in the case of the rejected resident moving notification for a park tent underscores the complex interplay between the factual reality of where an individual lives and the legal and societal recognition of that place as a formal "residence." The Court's reliance on "societal common sense" and the emphasis on the illegality of the appellant's living situation highlight the normative considerations that can influence the determination of a "principal place of living" for resident registration purposes in Japan. While concise, the judgment provides a clear indication that living arrangements deemed to be in contravention of law and lacking the basic, socially recognized attributes of a home are unlikely to be accepted as official residences within the Japanese legal framework for resident registration. This ruling has significant implications for how "residence" is defined and for the ability of individuals in non-traditional or legally precarious housing situations to access systems and services tied to having a registered address.