Defining Public Service Employment: A 1974 Supreme Court Look at "Operational" Workers

Judgment Date: July 19, 1974

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

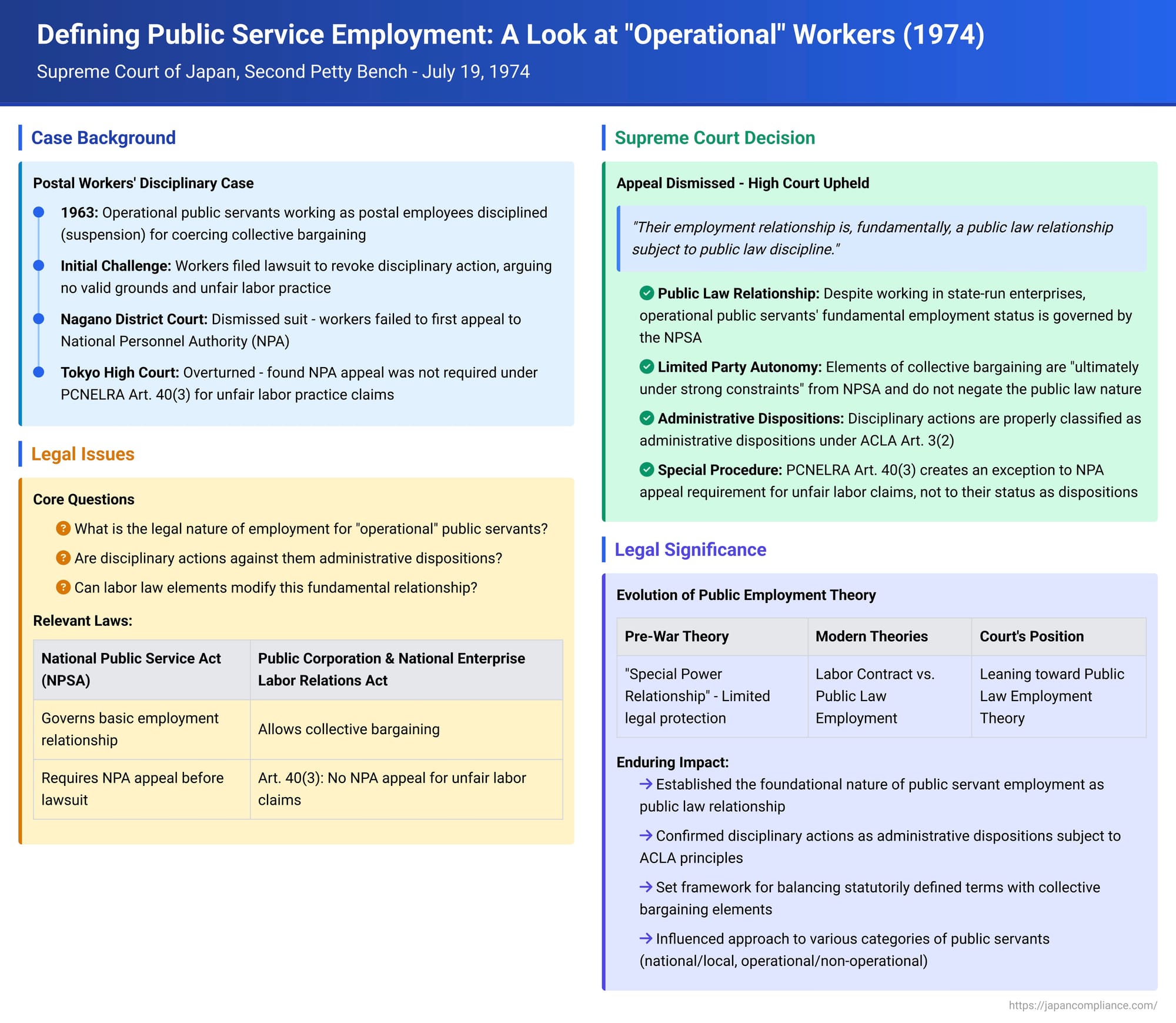

The legal nature of the employment relationship for public servants in Japan has long been a subject of debate. A pivotal 1974 Supreme Court decision involving disciplined postal workers provided crucial insights, particularly concerning "operational" public servants—those engaged in state-run enterprises. The ruling clarified that their employment is fundamentally a public law relationship, and disciplinary actions against them constitute administrative dispositions, even amidst a complex web of labor laws and procedural requirements.

The Postal Workers' Disciplinary Action and the ensuing Legal Challenge

The case involved X et al., who were "operational" general-category national public servants working as postal employees. In 1963, they were subjected to disciplinary suspension orders by Y, the then-Director of the Post Office. The grounds for discipline, invoked under Article 82, Paragraph 1 of the National Public Service Act (NPSA), included allegations of coercing collective bargaining.

X et al. launched a legal challenge to revoke these disciplinary actions. They argued two main points: first, that there were no valid grounds for the disciplinary measures, and second, that the actions constituted unfair labor practices, which are prohibited under Article 7 of the Labor Union Act.

The procedural journey of the case was complex:

- The Nagano District Court (First Instance) dismissed their lawsuit. It found the suit unlawful because the plaintiffs had not first appealed the disciplinary actions to the National Personnel Authority (NPA), a body responsible for overseeing public service personnel matters. This prior internal appeal was generally required by NPSA Article 92-2 before a court case could be initiated.

- The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance) overturned the District Court's decision. The High Court focused on a provision in the then-existing Public Corporation and National Enterprise Labor Relations Act (PCNELRA). Article 40, Paragraph 3 of the PCNELRA stipulated that if a challenge to an adverse disposition against an operational national public servant was based on the claim that it constituted an unfair labor practice, an appeal to the NPA could not be filed. Given this specific provision, the High Court concluded that the requirement for a prior NPA review did not apply in this instance and remanded the case back to the District Court for a hearing on the merits. The Post Office Director (Y) then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Affirming the Public Law Nature

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y, thereby upholding the High Court's decision to allow the case to proceed without prior NPA review on the unfair labor practice claim. In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court extensively discussed the legal nature of the employment relationship for operational public servants and the character of disciplinary actions against them.

1. A Public Law Relationship at its Core:

The Court began by establishing that operational public servants, like the postal workers in this case who worked for a state-run enterprise (as defined in PCNELRA Art. 2(1)(ii)(a)), are indeed general-category national public servants under the NPSA (Art. 2(2)). They are employed by national administrative organs. Critically, the fundamental aspects of their employment relationship—including appointment, status guarantees (分限 - bungen), discipline (懲戒 - chōkai), and service duties (服務 - fukumu)—are almost entirely governed by the detailed provisions of the NPSA and the rules issued by the NPA. Based on these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that "their employment relationship is, fundamentally, a public law relationship subject to public law discipline".

2. Limited Party Autonomy Doesn't Change Fundamental Nature:

The Court acknowledged certain unique aspects of operational public servants' employment. They work in enterprises engaged in economic activities, even if these are state-run. Furthermore, the PCNELRA, which applied to them, allowed for collective bargaining over terms and conditions of employment and the conclusion of collective labor agreements (PCNELRA Art. 8). The PCNELRA also partially excluded the application of the NPSA while making other labor laws—such as the Labor Standards Act, the Labor Union Act, and the Labor Relations Adjustment Act—applicable to these workers (PCNELRA Art. 40(1)). These elements suggested that, unlike "non-operational" national public servants to whom the NPSA applied in full, the employment relationship of operational public servants possessed "aspects left to party autonomy to some extent".

However, the Supreme Court emphasized that even these elements of party autonomy were "ultimately under strong constraints from the NPSA and NPA rules". Therefore, these aspects could not "negate the fundamental public law nature of their employment relationship".

3. Disciplinary Actions as Administrative Dispositions:

The Supreme Court then addressed the nature of adverse dispositions (like the disciplinary suspensions in this case). The NPSA stipulates that individuals subjected to adverse dispositions can file a request for review (an administrative appeal) with the NPA under the Administrative Appeal Act. Moreover, a lawsuit seeking the revocation of such a disposition generally cannot be filed until after the NPA has rendered a decision on that appeal (NPSA Art. 92-2).

Considering these statutory provisions in conjunction with the established public law nature of the employment relationship, the Supreme Court found it inescapable that "current positive law naturally presupposes that such adverse dispositions are administrative dispositions" (as defined in Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act - ACLA). The Court explicitly stated that PCNELRA Article 40, Paragraph 3 (which barred NPA appeals for unfair labor practice claims) "does not indicate an intention to deny that adverse dispositions are administrative dispositions".

Unpacking the Judgment: Historical Context and Legal Theories

The Supreme Court's 1974 decision is a cornerstone in the Japanese legal understanding of public service employment, marking a departure from older theories and navigating complex statutory interactions.

From "Special Power Relationship" to Modern Understandings:

Before World War II, the dominant legal theory, inherited from German public law, characterized the relationship between public servants and the state as a "special power relationship" (tokubetsu kenryoku kankei). This theory, also applied to relationships like prison incarceration and enrollment in state schools, posited that once such a relationship was established (through law or consent), the ordinary principles of the rule of law (legality) were largely excluded. The state could issue unilateral commands and impose duties without specific statutory grounding, and access to judicial remedies for the individual was severely limited. Public servant appointments under this theory were viewed as administrative acts based on consent.

However, this "special power relationship" theory is widely considered incompatible with Japan's post-war Constitution and the modern public servant system. Post-war legislation, like the NPSA, meticulously defines the terms and conditions of public employment (a principle known as kinmu jōken hōtei shugi, or the system of legally defined working conditions). Moreover, laws explicitly state that adverse dispositions against public servants (like dismissals or suspensions) are "administrative dispositions" subject to judicial review via revocation lawsuits (NPSA Art. 92-2; Local Public Service Act Art. 51-2). This has led to extensive academic debate about the precise legal nature of public employment under current law.

Competing Theories on Public Employment:

- Labor Contract Theory (rōdō keiyaku setsu): This theory views public service employment as a "special labor contract relationship heavily regulated by law". Proponents argue that public servants, like private-sector employees, are "workers" under Article 28 of the Constitution (which guarantees labor rights). The employment relationship is formed by mutual agreement, and its essence, despite state control, is not fundamentally different from private employment. There's also room for collective agreements within the statutory framework. This theory tends to see appointment and dismissal as contractual acts, with specific laws "artificially" constituting them as administrative dispositions for procedural purposes (this is sometimes called the "formal administrative disposition theory").

- Public Law Employment Relationship Theory (kōhōjō no kinmu kankei setsu): While acknowledging that the "special power relationship" concept is largely obsolete under current law, this theory rejects equating public employment with private labor contracts. It emphasizes the public nature of a public servant's duties and argues that this warrants a special legal status. Thus, public employment is a "special public law employment relationship". Like the older theory, it still often describes appointment as an administrative act based on consent.

- Modern Prevailing View (kyō no yūryoku setsu): A significant strand of modern scholarship questions the practical utility of rigidly adhering to either the labor contract or the public law employment theory. Since the employment relationship is so comprehensively detailed by statutes, the choice of underlying theory rarely leads to different concrete legal interpretations. For instance, both theories would likely agree that an appointment lacking the individual's consent is void, and that adverse actions like dismissal are administrative dispositions as per statute.

The Supreme Court's Leanings and Emphasis on Statutory Framework:

While some pre-1974 Supreme Court decisions had explicitly used the term "special power relationship," this particular judgment, and subsequent ones, have refrained from using it. The 1974 decision clearly establishes the "public law nature" of the employment relationship for operational national public servants. The Court's investigating judge for this case suggested that this finding (Point I of the judgment) is the primary basis for universally treating adverse dispositions as administrative acts, regardless of whether an NPA appeal is available. This interpretation would imply a rejection of the Labor Contract Theory, which might only consider such acts as administrative dispositions if a specific law (like one providing for an NPA appeal) designates them as such. Thus, the judgment appears to lean towards the Public Law Employment Relationship Theory.

However, commentators also point to a Supreme Court decision issued just six months prior (February 28, 1974), which denied the administrative disposition nature of disciplinary actions against employees of the then-Japan National Railways (JNR). JNR employees were not NPSA public servants but were covered by the PCNELRA. That decision reasoned that JNR's actions were generally private law acts, and for them to be treated as quasi-administrative acts would require an explicit statutory basis, which was lacking for disciplinary measures. While the logic regarding the public law nature (Point I) and the statutory framework for appeals (Point III) in the current postal workers' case aligns with the JNR case, the JNR case investigator reportedly emphasized the lack of statutory basis for administrative act characterization in that instance. Given that other areas of administrative law often look to statutory appeal procedures to determine if an act is a "disposition," some scholars argue that the 1974 postal workers' judgment, too, places more weight on the NPSA's general framework treating adverse actions as administrative dispositions (Point III) than on the abstract "public law relationship" (Point I). This interpretation might align the decision more closely with the Modern Prevailing View, which emphasizes adherence to the specific provisions of positive law.

The Judgment's Reach: Implications for Different Types of Public Servants

The system of "operational national public servants" as it existed in 1974 (e.g., postal workers) has largely been dismantled due to privatizations and reforms. Today, the ruling directly applies to national public servants covered by the Act on Labor Relations of Administrative Execution Corporations, which succeeded the PCNELRA.

However, the judgment's logic has broader implications:

- "Non-operational" General-Category Public Servants (National and Local): These public servants generally do not have the right to conclude collective bargaining agreements (meaning less party autonomy). Their employment relationship is undoubtedly one of public law. Adverse dispositions against them are comprehensively subject to administrative appeal processes. Therefore, under the logic of this Supreme Court judgment (especially Point III), such dispositions are clearly administrative dispositions.

- "Operational" Local Public Servants: This category presents a slightly different picture. They are generally granted the right to conclude collective bargaining agreements. However, unlike their national counterparts under the NPSA, adverse dispositions against them are often not subject to review through general administrative grievance systems. While their capacity for collective bargaining does not negate a public law relationship (as per Point II of the judgment), the absence of appeal routes (a key element in Point III) could, arguably, lead to a different conclusion on the administrative disposition status if Point III is given primary weight. Despite this, Supreme Court precedents have consistently affirmed that adverse dispositions against operational local public servants are administrative dispositions. This consistent affirmation for local operational staff might suggest the Supreme Court fundamentally leans towards the Public Law Employment Relationship Theory (Theory 2), which posits an inherent public law nature to the relationship and its consequences, irrespective of specific appeal routes for every type of dispute.

In summary, the prevailing stance in Japanese case law today, influenced by this 1974 decision, is to treat the employment relationship of almost all public servants—whether national or local, operational or non-operational—as a public law relationship, and to consider all adverse dispositions against them as administrative dispositions subject to judicial review.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance in Defining Public Employment Law

The 1974 Supreme Court decision concerning disciplined postal workers remains a critical judgment in Japanese public employment law. It firmly established the public law character of the employment relationship for operational national public servants and affirmed that disciplinary actions against them are administrative dispositions. While navigating a complex statutory landscape that included elements of both public service law and general labor law, the Court prioritized the overarching public law framework governing such employment. The decision also provided a key interpretation regarding procedural pathways for challenging these dispositions, particularly when allegations of unfair labor practices intersect with standard disciplinary grounds. Its reasoning continues to inform the understanding of public service employment and the rights and obligations of public servants in Japan.