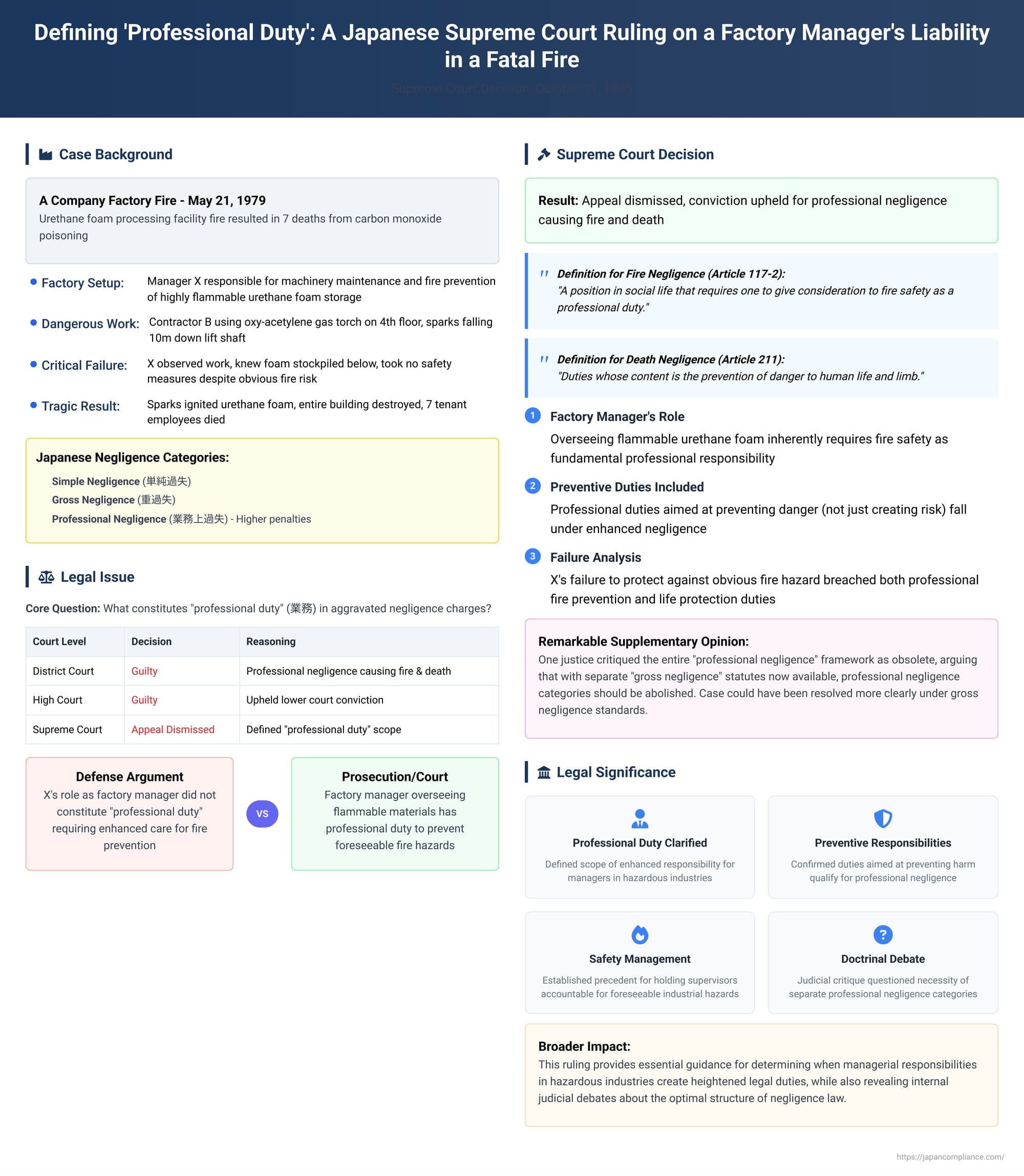

Defining 'Professional Duty': A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on a Factory Manager's Liability in a Fatal Fire

On October 21, 1985, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a decision that, while confirming the criminal conviction of a factory manager in a fatal fire, also laid bare a deep-seated doctrinal debate within Japanese negligence law. The case is pivotal not only for how it defines the scope of "professional duty" in the context of aggravated negligence but also for a remarkable supplementary judicial opinion questioning the very necessity of the legal category itself. The ruling provides a fascinating look into how Japanese law holds supervisors accountable for failing to prevent foreseeable tragedies.

The Incident: A Predictable Tragedy

The case originated from a catastrophic fire at a factory owned by Company A, a business engaged in the processing and sale of urethane foam. The defendant, referred to as X, was the manager of the factory division. His responsibilities explicitly included the maintenance of the factory's machinery and, crucially, the management and storage of the highly flammable urethane foam, which encompassed all related fire prevention duties.

On May 21, 1979, a contractor, Company B, was on-site to perform repair work on a simple freight lift. The work, supervised by the contractor's foreman, involved using an oxy-acetylene gas torch to cut and expand a hole in a steel plate on the fourth floor of the factory.

Defendant X was present on the fourth floor, personally observing and monitoring this hazardous work. Directly below the cutting operation, the lift shaft was open down to the first floor, a drop of approximately 10 meters. On that first floor, adjacent to the lift shaft opening, massive quantities of raw and semi-finished urethane foam were piled high in a materials storage area.

X was fully aware of the situation. He knew that using the cutting torch would generate a large shower of sparks and molten metal. He knew these sparks would fall directly down the open lift shaft. He was also fully aware of the large stockpiles of highly flammable foam on the first floor directly in the line of fire. The court found that X could have, and should have, easily foreseen that falling sparks would ignite the foam, leading to a major fire.

Despite this clear and immediate danger, X took no preventative measures. He did not order a fire-resistant sheet to be placed over the opening, nor did he ensure the foam was moved to a safe distance. He did not even conduct a safety check of the first-floor area. Instead, he implicitly permitted the contractor to begin and continue the dangerous cutting work.

The inevitable happened. A shower of sparks rained down the lift shaft, igniting the urethane foam below. The fire spread with incredible speed, fueled by the foam. The entire factory building was destroyed. Tragically, seven employees of a tenant in the building were unable to escape and died from carbon monoxide poisoning.

The District Court and the High Court both found X guilty of professional negligence in causing a fire (業務上失火) and professional negligence causing death (業務上過失致死), sentencing him to prison. He subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Legal Question: What Constitutes a "Professional" Duty?

The central legal issue before the Supreme Court was not whether X was negligent—his fault was plain—but whether his negligence rose to the level of "professional" negligence. In Japanese criminal law, negligence is typically divided into three tiers:

- Simple Negligence (単純過失)

- Gross Negligence (重過失), involving a severe lack of care.

- Professional Negligence (業務上過失), which applies to negligence committed in the course of one's "gyōmu" (業務)—a term encompassing one's profession, business, or duties.

Both professional negligence and gross negligence are "aggravated" forms of negligence, carrying significantly heavier penalties than simple negligence. The prosecution had charged X under the professional negligence statutes. Therefore, the appeal hinged on the precise legal definition of "gyōmu" as it applied to X's role and his failure to act. The court had to determine if his position as a factory manager overseeing flammable materials and supervising a contractor constituted a "professional duty" under two distinct articles of the Penal Code: one concerning the negligent spread of fire, and the other concerning negligently causing death.

The Supreme Court's Definitions

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal and upheld the conviction. In its reasoning, the court provided clear and authoritative definitions for "professional duty" in these contexts, effectively unifying the concept around the idea of preventing foreseeable harm.

1. "Professional Duty" in Causing a Fire (Article 117-2)

The court defined the term "業務" (gyōmu) for the crime of professional negligence in causing a fire as:

"...a position in social life that requires one to give consideration to fire safety as a professional duty."

The court found that X's position fit this definition perfectly. As the manager of a factory whose core business involved handling and storing a notoriously flammable substance like urethane foam, a duty to prevent fire was not merely an incidental task but a fundamental part of his professional responsibilities. His role inherently and continuously demanded a high level of attention to fire safety. Therefore, his failure to act in the face of an obvious fire hazard was a direct breach of this professional duty.

2. "Professional Duty" in Causing Death (Article 211)

Next, the court defined "gyōmu" for the crime of professional negligence causing death. It stated that the term:

"...includes duties whose content is the prevention of danger to human life and limb."

This was a significant clarification. Previous judicial interpretations often focused on "professional duties" that themselves created a risk to others (e.g., driving a vehicle, performing surgery). This decision explicitly affirmed that duties aimed at preventing danger are also included. X's responsibility for fire prevention was precisely such a duty; its entire purpose was to avert a disaster that could foreseeably harm or kill people. By failing in his fire prevention duty, he simultaneously failed in his professional duty to protect human life.

The court concluded that X, as the person responsible for the factory division, was engaged in the professional duty of managing flammable urethane foam, a duty that naturally entailed the prevention of fire. When he failed in this duty, leading to a fire that caused fatalities, he was correctly found liable for both professional negligence in causing the fire and professional negligence causing death.

A Judge's Critique: The Redundancy of "Professional Negligence"

While the majority opinion was straightforward, the case is most remembered for the supplementary opinion written by one of the justices. This opinion, while agreeing with the final verdict, presented a powerful critique of the very legal framework the court was applying.

The justice began by questioning the fundamental reason for punishing "professional negligence" more harshly. The justification, he noted, is that a person engaged in a professional duty has a higher duty of care than an ordinary person, and a breach of that heightened duty warrants a stiffer penalty.

However, he then launched into a historical and legislative critique. He pointed out that the statute for professional negligence causing death existed in the Japanese Penal Code for over 30 years before a separate statute for gross negligence causing death was introduced. During that long period, when faced with egregious cases of carelessness that seemed to deserve more punishment than "simple negligence," courts had only one tool to work with: the "professional negligence" statute. Consequently, to achieve what they felt was a just outcome, judges often stretched the definition of "professional duty" to its limits, applying it to situations far removed from any conventional understanding of a profession.

The problem, the justice argued, is that this historical artifact persists today. The Penal Code now contains distinct articles punishing "gross negligence" for both causing a fire and causing death. In his view, this makes the separate category of "professional negligence" largely obsolete and doctrinally confusing.

He applied this critique directly to the case at hand. X's conduct, he argued, was a textbook example of gross negligence. He foresaw that his inaction would likely lead to a fatal fire and yet did nothing to take even the most basic precautions. The case could have been resolved cleanly and directly under the gross negligence statutes. Instead, he lamented, the court was forced to engage in "fruitless" and laborious interpretive exercises to fit the facts into the "professional negligence" box, simply because the law exists.

He concluded with a striking thought: while he personally believes the "professional negligence" statutes have "lost their reason for being" and should be abolished, the court must apply the law as written. Therefore, as long as the statutes and the body of precedent supporting them exist, the only viable path is to interpret them as the majority did—in a way that essentially treats "professional negligence" and "gross negligence" as provisions aimed at the same target: a degree of carelessness so severe that it demands heightened punishment.

Conclusion: A Dual Legacy

The 1985 factory fire decision stands as a landmark for two distinct reasons. First, it provides a clear and practical definition of the "professional duty" that attaches to managers and supervisors in hazardous industries. It confirms that the responsibility for safety is not a passive role but an active, professional duty to prevent foreseeable harm to both property and, most importantly, human life.

Second, through its incisive supplementary opinion, the case offers a rare window into the internal debates of Japan's highest court. It highlights the tension between applying established law and questioning its contemporary relevance. The decision is thus both a guide for how to interpret the law of professional negligence and a powerful argument that the law itself may be in need of reform, suggesting that a more streamlined focus on the degree of negligence—simple versus gross—might serve justice more effectively.