Defining 'Minimum Living': Japan's Supreme Court on Welfare Standard Revisions and Ministerial Discretion

A Third Petty Bench Ruling from February 28, 2012

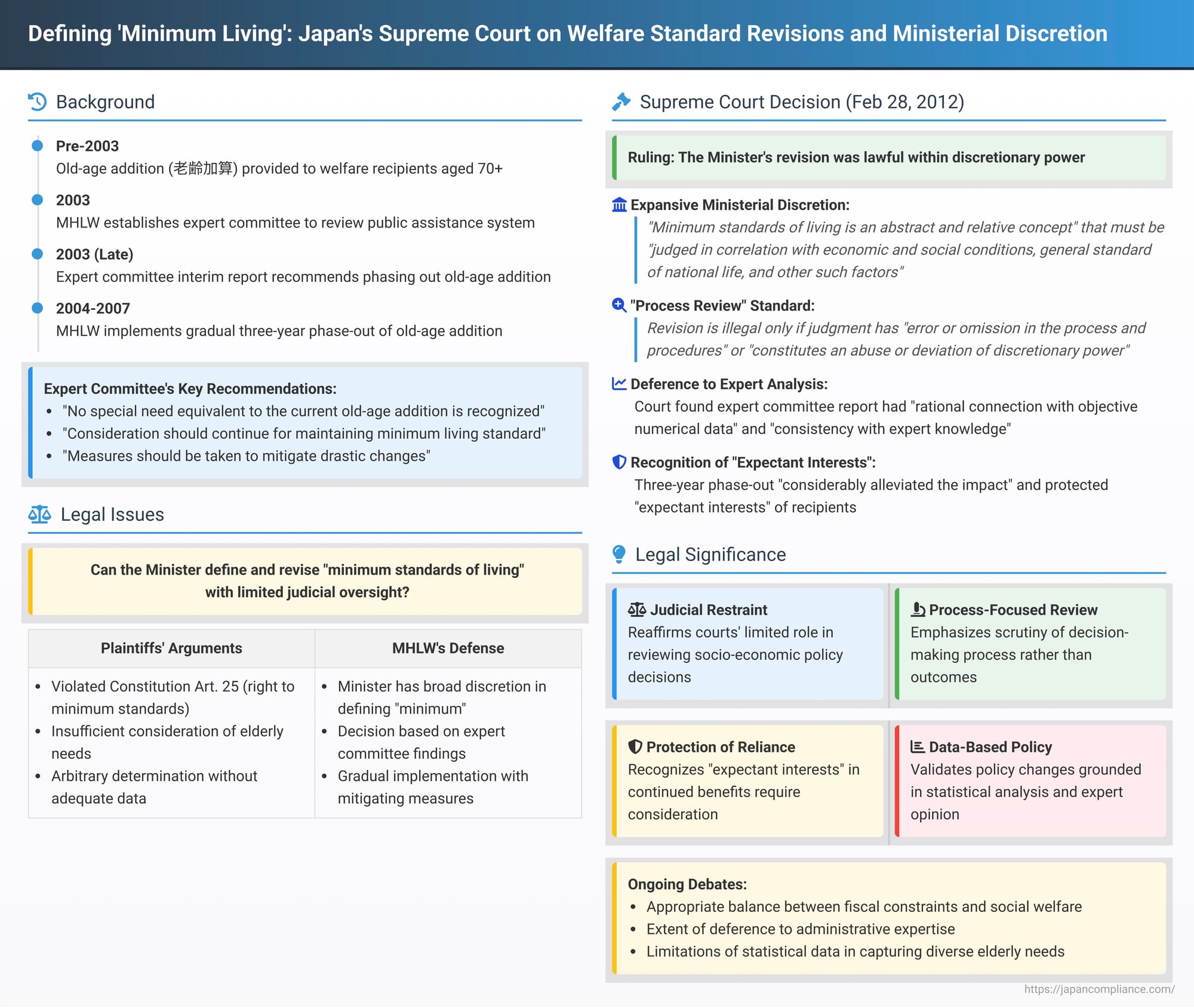

The concept of "minimum standards of living" lies at the heart of social welfare systems worldwide, yet its precise definition and implementation pose continuous challenges for governments and judiciaries alike. In Japan, this issue came under sharp focus in a series of cases culminating in Supreme Court judgments in 2012. These cases scrutinized the decision by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to phase out a long-standing "old-age addition" to public assistance benefits. This blog post will primarily examine the reasoning of the Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench in its ruling on February 28, 2012 (Heisei 22 (Gyo Tsu) No. 392, (Gyo Hi) No. 416), often referred to as Judgment ① in related legal commentaries.

The "Old-Age Addition" and Its Revision

Under Japan's Public Assistance Act (生活保護法 - Seikatsu Hogo Hō), the MHLW Minister is tasked with establishing the "public assistance standards" (保護基準 - hogo kijun) that dictate the level of support provided to those in need. These standards, typically set forth in an MHLW Notification (a form of administrative regulation), for many years included an "old-age addition" (老齢加算 - rōrei kasan). This was a supplementary payment provided as part of livelihood assistance, generally to individuals aged 70 and older.

In 2003, amid broader fiscal pressures and social security reviews, the MHLW convened an expert committee (専門委員会 - senmon iinkai) within its Social Security Council to examine the public assistance system, including the old-age addition. This committee subsequently published an interim report ("中間とりまとめ" - chūkan torimatome) containing several key points:

- (ア) After comparing the consumption expenditures of single, unemployed elderly individuals in low-income households, the committee concluded that "no special need equivalent to the current old-age addition is recognized for those aged 70 or older; therefore, the old-age addition itself should be reviewed with a view to abolition".

- (イ) However, the report also stipulated that "consideration should continue to be given to maintaining the minimum living standard of elderly households within the protection standard system, taking into account the expenses necessary for their social life".

- (ウ) Furthermore, it recommended that "measures should be taken to mitigate drastic changes so that the living standards of protected households do not decline suddenly".

Acting upon these recommendations, the MHLW Minister initiated a series of revisions to the public assistance standards from fiscal year 2004 onwards. These changes (referred to as "本件改定" - honken kaitei, or "the present revisions") involved incrementally reducing and ultimately phasing out the old-age addition over a three-year period.

The Legal Challenge by Welfare Recipients

The plaintiffs in Judgment ① were recipients of public assistance residing in Tokyo. Following the implementation of the revised standards, their local welfare offices issued decisions reducing their livelihood assistance payments due to the elimination of the old-age addition. The plaintiffs challenged these decisions in court, arguing that the MHLW's underlying revision of the public assistance standards was unlawful and unconstitutional. They asserted that the revisions violated Article 25 of the Constitution of Japan (which guarantees the right to maintain minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living) and several provisions of the Public Assistance Act, including Articles 3 and 8(2) which operationalize this constitutional right. While some lower courts in related cases found for the plaintiffs (notably the appellate court in a similar case referred to as Judgment ②), the claims of the Tokyo plaintiffs in Judgment ① had been dismissed by the lower courts.

The Supreme Court's Decision (Judgment ① - February 28, 2012)

The Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench dismissed the appeal of the Tokyo plaintiffs, thereby upholding the MHLW Minister's revision of the standards as lawful in their specific cases.

Minister's Broad Discretion Affirmed:

The Court began by reiterating the extensive discretion granted to the MHLW Minister in determining the specifics of "minimum standards of living" and setting public assistance levels.

- It stated that the "minimum standards of living" mentioned in Article 25 of the Constitution and Articles 3 and 8(2) of the Public Assistance Act is an "abstract and relative concept". Its concrete content is not fixed but must be "judged and determined in correlation with the economic and social conditions of the time, the general standard of national life, and other such factors".

- To embody this abstract concept in concrete public assistance standards necessitates "a high degree of expert technical consideration and policy judgment based thereon". This cited the Supreme Court's 1982 Grand Bench decision in the Horiki case, a landmark precedent concerning judicial review of social welfare benefits.

- Consequently, when revising parts of the standards like the old-age addition, the MHLW Minister is recognized as having discretion from an "expert technical and policy standpoint". This discretion covers judging whether a "special need" attributable to old age genuinely exists and whether the revised livelihood assistance standards for the elderly remain sufficient to "maintain a healthy and cultured living standard".

Acknowledging "Expectant Interests" of Recipients:

The Court also addressed the impact of such revisions on individuals already receiving benefits.

- It acknowledged that the "abolition of the old-age addition could not be denied to have an aspect of causing a loss of their expectant interest (期待的利益 - kitaiteki rieki), which had been concretized by the protection standards," for those recipients who had based their life plans on the assumption of its continued provision.

- In light of this, the MHLW Minister, when deciding on the specific methods of abolition, "also has discretion from the aforementioned expert technical and policy standpoint, including regarding the necessity of measures to mitigate drastic changes (激変緩和措置 - gekihen kanwa sochi), in order to give due consideration as much as possible to these expectant interests of the protected persons".

Standard of Judicial Review – "Process Review":

The Supreme Court then laid out the standard by which it would review the Minister's exercise of this discretion. The revision of the standards involving the abolition of the old-age addition would be deemed illegal if:

- The Minister's judgment (e.g., that no special need for the addition for those aged 70 and above exists, and that the revised standards are still adequate) is found to have "an error or omission in the process and procedures of judgment regarding the concretization of minimum standards of living," or if it otherwise constitutes an abuse or deviation of discretionary power. This method of review is often referred to as "process review" (判断過程審査 - handan katei shinsa).

- The Minister's decision regarding whether to adopt mitigating measures (and the specific measures chosen, if any) is found to be an abuse or deviation of discretion when viewed from the perspective of the "expectant interests of the protected persons and the impact on their lives".

Court's Application of the Standard to the Facts:

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court found the MHLW's actions in this instance to be lawful:

- Regarding the Judgment on "Special Need": The Court noted that the expert committee's interim report (specifically point (ア) recommending abolition) was based on various statistical analyses, including comparisons of consumption expenditures between different elderly age groups and income brackets, trends in assistance standards versus the CPI, and changes in Engel's coefficient. The Supreme Court found that this report exhibited "no lack of rational connection with objective numerical data such as statistics, or consistency with expert knowledge". Since the MHLW Minister's decision to abolish the old-age addition due to a lack of special need aligned with this expert opinion, and there were "no circumstances suggesting any error or omission in the judgment process and procedures," this aspect of the Minister's decision was upheld.

- Regarding the Mitigating Measures: The MHLW implemented the abolition of the old-age addition gradually over a three-year period, a method consistent with the expert committee's recommendation (point (ウ)). The Court considered data indicating that households receiving the old-age addition had net savings close to the amount of the addition and significantly higher than households not receiving it. Based on this, the Court concluded that the three-year phase-out "can be evaluated as having considerably alleviated the impact on protected households". Furthermore, ongoing periodic reviews of the overall livelihood assistance standards by the MHLW were seen as an effort to prevent sudden drops in living standards, in line with the committee's point (イ) about maintaining minimum living standards for the elderly. Therefore, the reduction in assistance resulting from the abolition of the old-age addition "cannot be evaluated as having had an undeniable impact on their lives through the loss of expectant interest".

The Supreme Court thus concluded that the MHLW Minister's revision of the public assistance standards did not constitute an abuse or deviation of discretion and was, therefore, not illegal.

Key Legal Concepts in Play

This case illuminates several important legal concepts within Japanese administrative and constitutional law:

- "Minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living": Enshrined in Article 25 of the Constitution, this right is fundamental but its specific content is deemed "abstract and relative," allowing for administrative interpretation based on prevailing conditions.

- Ministerial Discretion: The MHLW Minister enjoys broad discretion in setting public assistance standards. This is justified by the complex, technical, and policy-driven nature of defining "minimum living". The legal commentary indicates that established case law views this discretion as "extremely broad".

- "Expectant Interests" and Protection of Reliance (信頼保護 - shinrai hogo): The Court explicitly recognized that beneficiaries may have "expectant interests" in the continuation of benefits. When making adverse changes, the administration should consider these interests, often by implementing transitional or mitigating measures. This aligns with the broader administrative law principle of "protection of reliance". A separate opinion by Justice Sudō in a related case (Judgment ②) even suggested that taking such mitigating measures is a constitutional duty.

- "Process Review" (判断過程審査 - handan katei shinsa): This is the judicial methodology employed by the Court to review the Minister's discretionary decision. Instead of directly substituting its own judgment on the substance of the standards, the Court focuses on the process by which the Minister reached the decision—examining for errors, omissions, or lack of rationality in that process. This approach has been used in other landmark cases involving broad administrative discretion, such as those concerning nuclear power plant permits and textbook censorship. Its application to law-creating administrative regulations like the public assistance standards is a notable feature.

The Weight of Expert Advice and Data

The Supreme Court's ruling demonstrates significant deference to the findings of the MHLW's expert committee, provided those findings are themselves rationally derived.

- The judgment emphasizes the importance of the administrative decision-making process having a "rational connection with objective numerical data such as statistics" and "consistency with expert knowledge". The presence of these elements makes it less likely for a court to find an abuse of discretion. The commentary suggests this focus on data and expertise could be a way to enhance the density and rigor of judicial review in such cases.

Brief Comparison with Judgment ② (Decided April 2, 2012)

A similar case involving plaintiffs from Kitakyushu City (Judgment ②) was decided by the Supreme Court's Second Petty Bench shortly after Judgment ①, on April 2, 2012. Judgment ② largely adopted the same legal framework regarding ministerial discretion and the standard of judicial review. However, in that case, the Fukuoka High Court (the appellate court) had found the MHLW's revision illegal. The High Court reasoned that the Minister had rushed the decision to abolish the old-age addition shortly after the expert committee's interim report was published and had not adequately considered the report's recommendations concerning the maintenance of overall living standards for the elderly (point (イ)) and the proper implementation of mitigating measures (point (ウ)). The Supreme Court, in Judgment ②, disagreed with the High Court's assessment of the MHLW's process. It stated that the expert committee's opinion was not legally binding on the Minister but rather one important factor for consideration. The Supreme Court found that the MHLW's revision process did not, in fact, ignore the overall intent of the expert committee's report and ultimately remanded that case back to the High Court for further consideration under the framework it had established.

Discussion and Critical Perspectives

These Supreme Court judgments, while affirming the MHLW's broad discretion, have prompted further discussion and some critical perspectives among legal scholars.

- The degree of deference shown to the Minister's policy choices remains a central point of debate.

- Concerns have been voiced as to whether the MHLW, in its decision-making process, gave sufficient weight to all aspects of the expert committee's interim report, particularly the more nuanced recommendations about ensuring the overall adequacy of living standards for the elderly (point (イ)) and the thoroughness of the mitigating measures (point (ウ)), rather than perhaps focusing more heavily on the recommendation to abolish the specific "old-age addition" (point (ア)).

- Some commentators have questioned whether the statistical data and analyses used fully captured the complex realities of the living conditions and diverse needs of impoverished elderly individuals, especially those living alone, and have pointed to potential transparency issues in the underlying statistical processes.

- More broadly, these cases highlight the inherent challenges courts face when called upon to review complex socio-economic policy decisions embedded within administrative regulations, which often involve balancing competing societal values, expert assessments, and budgetary realities. The "process review" framework offers a pathway for judicial oversight, but its effectiveness can depend on the rigor with which courts scrutinize the rationality and completeness of the administrative decision-making process.

Conclusion

The 2012 Supreme Court judgments concerning the revision of the old-age addition to public assistance are significant for delineating the scope of ministerial discretion in the vital area of social welfare standard-setting in Japan. They affirm that the MHLW Minister possesses considerable authority to adapt public assistance standards based on expert advice and policy considerations. However, this discretion is not absolute and is subject to judicial review through a "process-oriented" lens, which examines the rationality and procedural integrity of the Minister's decision-making. The explicit recognition of recipients' "expectant interests" and the necessity of considering mitigating measures when making adverse changes to benefits are important acknowledgments. These rulings underscore the ongoing effort to strike a balance between the state's responsibility to ensure minimum living standards, the need for responsive and evidence-based policymaking, fiscal constraints, and the protection of individuals who rely on established social welfare provisions.