Defining Medical Responsibility in Japan: Two Landmark Supreme Court Decisions on Duty of Care and Medical Standards

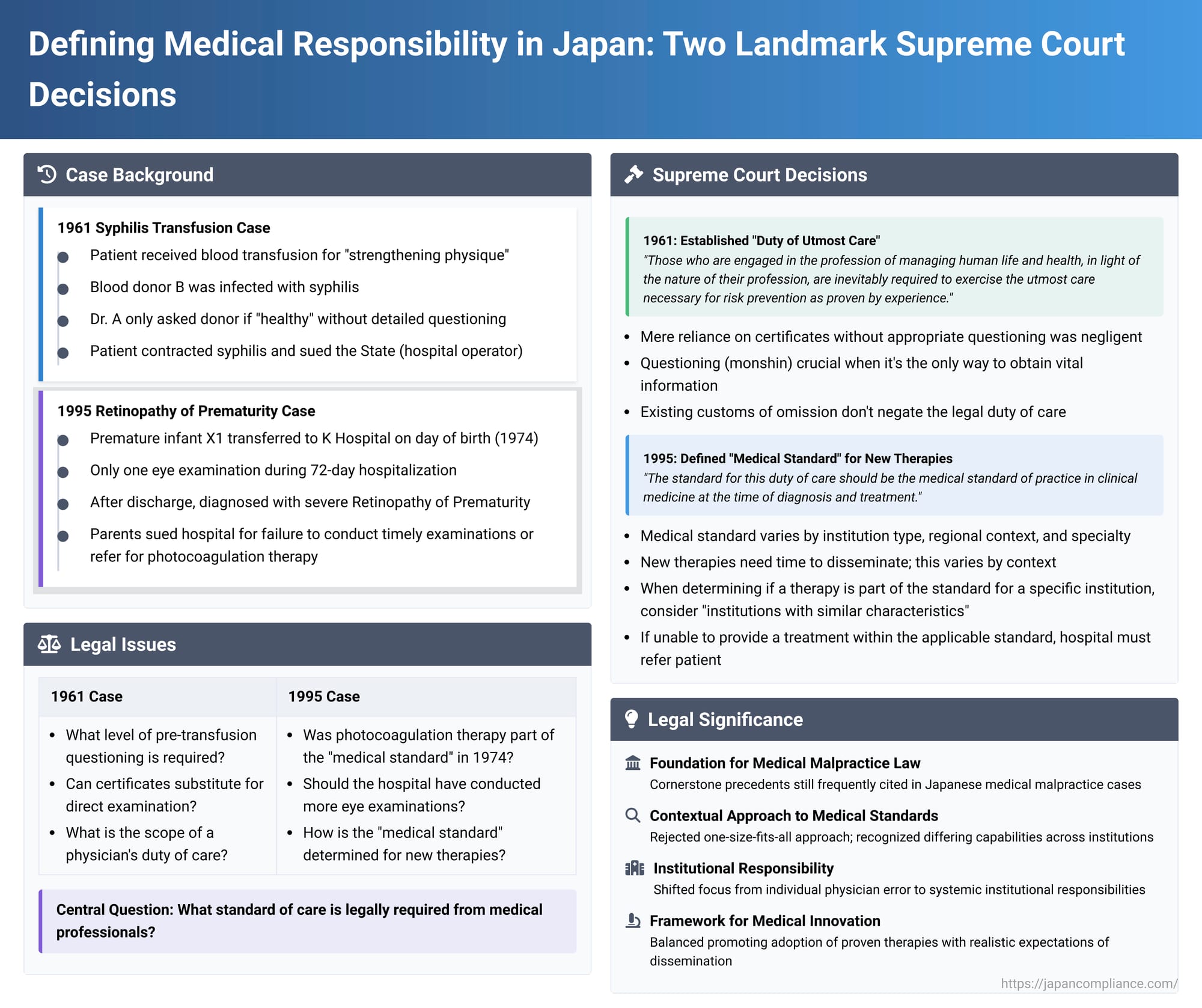

The landscape of medical liability in Japan has been significantly shaped by key judicial precedents. Among these, two Supreme Court decisions, one from 1961 and another from 1995, stand out for their profound impact on defining a physician's duty of care and the concept of the "medical standard." These cases, though decades apart, collectively articulate a high expectation for medical professionals while also acknowledging the evolving nature of medical science and practice. This article explores these two seminal rulings and their enduring legacy.

Case 1: The 1961 Syphilis Transfusion Case – Establishing the "Duty of Utmost Care"

Date of Judgment: February 16, 1961 (Showa 36)

Case Reference: Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, 1956 (O) No. 1065

The Facts:

The first case, often referred to as the "Syphilis Transfusion Case," involved a patient, Ms. X, who was admitted to a hospital operated by Y (the State) for the treatment of a uterine fibroid. During her hospitalization, she received a blood transfusion for the purpose of "strengthening her physique". The blood was sourced from a professional blood donor, B, by the attending physician, Dr. A. Tragically, donor B was infected with syphilis, and as a result, Ms. X also contracted the disease. Ms. X sued Y (the State) for damages based on vicarious liability for Dr. A's alleged negligence under Article 715 of the Civil Code.

Investigations revealed that Dr. A had not performed specific serological tests on donor B immediately before the transfusion, nor had he conducted a detailed physical examination (visual inspection, palpation, auscultation) for signs of syphilis. However, the lower courts did not find negligence in these omissions per se, likely because the donor possessed a certificate indicating a negative serological test and a blood bank membership card, suggesting prior health checks. Instead, the critical point of contention was the nature of Dr. A's questioning of the donor. Dr. A had merely asked donor B if he was "healthy" (「身体は丈夫か」) and did not pursue more specific inquiries sufficient to ascertain the potential risk of syphilis infection. The first and second instance courts found Dr. A negligent on this point of insufficient questioning and awarded partial damages to Ms. X. The State (Y) appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (February 16, 1961):

The Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, upholding the lower courts' finding of negligence. The Court's reasoning was pivotal:

- Insufficiency of Certificates and Current Diagnostic Limitations: The Court stated that even if a blood donor presents seemingly reliable documents like a negative serological test certificate and a blood bank membership card, a physician cannot immediately conclude that there is no risk of syphilis infection from a transfusion. This was particularly true given the scientific limitations at the time in definitively diagnosing syphilis in its latent or incubation stages through available methods.

- The Duty of Medical Questioning (Monshin): The Court emphasized that while information gleaned from questioning might be secondary in accuracy compared to objective tests like serological reactions, visual inspections, palpations, or auscultations, there are situations where questioning (問診 - monshin) is the only available method to gather crucial information about matters not directly perceivable from the patient's (or donor's) body. Therefore, the physician has a duty to question the blood donor—the person most likely to be aware of their own risk factors—about matters that could help infer the presence of syphilis infection risk. This duty to make such inquiries to confirm the absence of risk, as far as circumstances permit (the Court noted that Ms. X's transfusion was not an immediate, life-or-death emergency), was deemed a "natural duty of care" (当然の注意義務 - tōzen no chūi gimu) for a physician. The judgment further noted that the donor B, although a professional blood donor, was not in a situation where he absolutely had to provide blood to earn a living at that specific time, and had he been thoroughly and concretely questioned, it could not be denied that the risk of syphilis might have been inferred.

- The "Duty of Utmost Care": Addressing the appellant's argument that such detailed questioning would impose an excessive burden on physicians, the Supreme Court delivered a powerful statement that has resonated through Japanese medical law ever since: "Those who are engaged in the profession of managing human life and health (medical practice), in light of the nature of their profession, are inevitably required to exercise the utmost care necessary for risk prevention as proven by experience (危険防止のために実験上必要とされる最善の注意義務 - kiken bōshi no tame ni jikkenjō hitsuyō to sareru saizen no chūi gimu)." This established the principle of a "duty of utmost care" for medical professionals.

- Negligence in Omission: Since Dr. A failed to conduct such appropriate questioning—when doing so might have allowed him to infer the risk of syphilis from donor B—and instead proceeded with the transfusion based only on a cursory inquiry, his actions were found to constitute a breach of this duty of care, leading to liability for the resulting harm. The Court rejected the argument that a prevailing custom of omitting such questioning if certificates were present would negate this duty, stating that the existence of a duty of care is a legal judgment, and such a custom would only be a factor in assessing the degree of negligence.

Significance: The 1961 Syphilis Transfusion Case was groundbreaking for explicitly articulating this "duty of utmost care" expected of medical practitioners in Japan. It set a high bar for the level of diligence required, emphasizing the profound responsibility that comes with managing human life and health.

Case 2: The 1995 Retinopathy of Prematurity Case – Defining the "Medical Standard" for New Therapies

Date of Judgment: June 9, 1995 (Heisei 7)

Case Reference: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, 1992 (O) No. 200

The Facts:

The second key case concerns X1, an infant born prematurely (31 weeks gestation, 1508 grams) who was transferred on the day of birth to K Hospital (Himeji Red Cross Hospital), an institution operated by defendant Y (Japanese Red Cross Society). A medical care contract was established between X1's parents (X2 and X3) and Y for X1's care, diagnosis, and treatment. Dr. A (a pediatrician) and other physicians were assigned to X1's care, which included oxygen therapy as needed. X1 was hospitalized for 72 days. During this entire period, only a single eye examination was conducted by the hospital's ophthalmologist, Dr. B; this occurred 16 days after X1's birth, and Dr. B found no particular changes and deemed a follow-up unnecessary at that point. After discharge, X1 was suspected by Dr. B of having an eye abnormality during a check-up and was subsequently diagnosed with severe Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) at Z Hospital (Hyogo Prefectural Children's Hospital), to which Dr. A had referred X1. ROP is a potentially blinding eye disorder that primarily affects premature infants.

X1 and his parents sued Y for damages, alleging a breach of the medical care contract due to the negligence of its employees, Drs. A and B (vicarious liability). The central issue was whether Drs. A and B were negligent in failing to perform timely and appropriate eye examinations on X1 with photocoagulation therapy (a then-emerging treatment for ROP) in mind, or, alternatively, for failing to transfer X1 to another medical facility capable of providing such examinations and treatment. The lower courts (first instance and High Court) dismissed the plaintiffs' claim. They reasoned that at the time of X1's birth (Showa 49 / 1974), photocoagulation therapy was not yet established as an effective treatment for ROP. Therefore, Drs. A and B could not be found negligent for not considering or facilitating this specific therapy. The plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 9, 1995):

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. Its reasoning provided a sophisticated framework for understanding the medical standard of care, particularly in relation to new and evolving treatments:

- Reaffirmation of the "Duty of Utmost Care" and its Link to the "Medical Standard": The Court began by referencing its 1961 Syphilis Transfusion Case, stating that Y, through its physicians, had a contractual obligation to conduct X1's medical care by "exercising the utmost care required by experience for risk prevention." Crucially, it then linked this high duty to a more concrete benchmark: "The standard for this duty of care should be the medical standard of practice (医療水準 - iryō suijun) in clinical medicine at the time of diagnosis and treatment."

- Determining the Medical Standard for New Therapies – A Contextual Approach: The Supreme Court acknowledged the complexities of incorporating new medical advancements into the standard of care:

- Diffusion Time for New Knowledge: New therapies, even if recognized as effective and safe by specialist researchers, require a certain period to become widely adopted in general clinical practice.

- Variability in Dissemination: The time taken for such dissemination can vary significantly based on factors such as the nature of the medical institution (e.g., teaching hospital vs. local clinic), its geographical location, the prevailing medical environment in that region, the specific medical specialties involved, etc. Furthermore, there's often a lag between the spread of knowledge about a new therapy and the availability of the necessary technology, equipment, and trained personnel to implement it. The Court noted that parties typically enter into medical care contracts with an implicit understanding of these realities.

- Individualized Assessment of Medical Standard: Therefore, the Court held that when deciding whether a particular new therapy should be considered part of the expected medical standard for a given medical institution, it is improper to apply a uniform, nationwide standard. Instead, "various circumstances such as the character of the said medical institution and the characteristics of the medical environment in the region where it is located should be considered."

- When New Knowledge Becomes the Standard for an Institution: The Court provided a test: "If knowledge regarding a new therapy has disseminated to a considerable extent among medical institutions possessing characteristics similar to the medical institution in question, and it is deemed reasonable to expect the said medical institution to possess such knowledge, then, absent special circumstances, that knowledge should be considered the medical standard for that institution."

- Institutional Duties Arising from the Medical Standard:

- Duty to Ensure Doctors Acquire Knowledge: If a certain level of knowledge is deemed part of an institution's medical standard, the institution has a duty to ensure that its physicians (as vicarious performers of the institution's contractual obligations) acquire and maintain that knowledge. If a physician's lack of such knowledge results in the institution failing to implement the appropriate therapy (or take other proper measures like referral) and the patient suffers harm, the institution can be held liable for breach of contract.

- Duty Regarding Technology and Equipment: This principle extends to the availability of necessary technology and equipment. If an institution does not possess the means to implement a therapy that is part of its expected standard (e.g., due to budgetary constraints or other reasons), it then has a duty to take other appropriate actions, such as transferring the patient to another suitably equipped medical facility.

Outcome of Remand (as per PDF summary): Following the Supreme Court's guidance, the Osaka High Court, on remand, re-evaluated the case. It considered the specific role K Hospital played in neonatal care within its prefecture and the extent to which knowledge about photocoagulation for ROP had disseminated by 1974-1975. The High Court ultimately found that, at the time of X1's birth, knowledge of photocoagulation therapy did constitute the medical standard applicable to K Hospital. Consequently, it found Dr. B negligent for failing to conduct timely eye examinations and for not taking steps to transfer X1 for potential treatment, and awarded damages to the plaintiffs.

Significance: The 1995 ROP case was instrumental in refining how the "medical standard" is determined in Japan. It moved away from a potentially rigid, one-size-fits-all approach, especially for new therapies, towards a more contextual and individualized assessment that considers the specific circumstances and capabilities of the medical institution in question.

Connecting the Dots: The Evolution from "Utmost Care" to a Contextual "Medical Standard"

These two landmark judgments, while distinct in their factual contexts (one concerning a direct act of transfusion with an immediate infectious outcome, the other concerning diagnostic and management omissions for an emerging condition), are intrinsically linked in the evolution of Japanese medical liability law.

The 1961 Syphilis Transfusion Case laid down the foundational principle of a very high "duty of utmost care" for medical professionals, rooted in the profound responsibility of safeguarding patient life and health. This principle, while setting a high bar, was somewhat abstract in its practical application across diverse medical scenarios.

The 1995 ROP Case did not dilute this high duty. Instead, it provided a crucial mechanism for its practical application by tethering it to the concept of the "medical standard of practice in clinical medicine at the time." The "medical standard" thus became the concrete benchmark against which the "utmost care" is measured. The 1995 ruling further sophisticated this by clarifying that this "medical standard" is not a monolithic entity but one that must be assessed in light of the specific institution's character, its operational environment, and the reasonable expectations regarding its knowledge and capabilities, particularly concerning new and evolving medical treatments.

This evolution reflects a legal maturation, balancing the need to hold the medical profession to a very high standard of diligence with a pragmatic understanding of how medical knowledge and technology diffuse through the healthcare system. It underscores that "utmost care" does not mean doctors must always provide the newest, most advanced treatment regardless of context, but rather that they must practice in accordance with a standard reasonably expected of their institution, which includes staying abreast of relevant advancements and acting appropriately on that knowledge—whether by providing treatment directly or by ensuring the patient has access to it elsewhere.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The combined impact of these two Supreme Court decisions has been far-reaching:

- Foundation for Medical Malpractice Litigation: They remain cornerstone precedents frequently cited in Japanese medical malpractice cases, providing the essential framework for evaluating physician and hospital negligence.

- The Enduring "Duty of Utmost Care": The principle of the "duty of utmost care" established in 1961 continues to signify the high level of responsibility expected from those in the medical field.

- Flexible and Contextual Medical Standard: The 1995 ruling's nuanced approach to the "medical standard" allows for a more equitable assessment of care, recognizing that not all hospitals can or should be judged by the capabilities of leading research institutions, especially concerning cutting-edge therapies. However, it also imposes a proactive duty on institutions to be aware of and adapt to advancements relevant to their specific roles and patient populations.

- Emphasis on Institutional Responsibility: The 1995 case, particularly by framing the hospital's liability in terms of breach of contract and focusing on institutional duties (to ensure staff knowledge, provide equipment, or arrange transfers), highlights a broader trend towards recognizing that medical negligence is not solely about individual physician error but can also involve systemic or organizational failings.

- Navigating Medical Advancements: These rulings provide a legal framework for how the healthcare system should respond to medical innovations. They encourage the adoption of proven new therapies by setting expectations for knowledge acquisition and resource allocation (or referral) based on an institution's specific context.

These decisions collectively reflect a careful judicial balancing act: protecting patients by demanding a high standard of care, while also ensuring that this standard is applied in a fair and realistic manner that considers the complexities of medical practice and the gradual nature of scientific progress. The PDF commentary notes that while the 1961 case was based on tort and the 1995 case on breach of contract, the content of the duty of care is generally considered similar in both legal frameworks.

Conclusion

The 1961 Syphilis Transfusion Case and the 1995 Retinopathy of Prematurity Case are more than just historical legal decisions; they are living principles that continue to shape the contours of medical responsibility in Japan. By establishing the "duty of utmost care" and then elaborating a contextual, evolving "medical standard" as its measure, the Japanese Supreme Court has provided an enduring framework for assessing the conduct of medical professionals and institutions. These rulings underscore a commitment to patient safety and high-quality care, while acknowledging the dynamic and challenging environment in which modern medicine is practiced. They remain essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the legal underpinnings of medical liability in Japan.