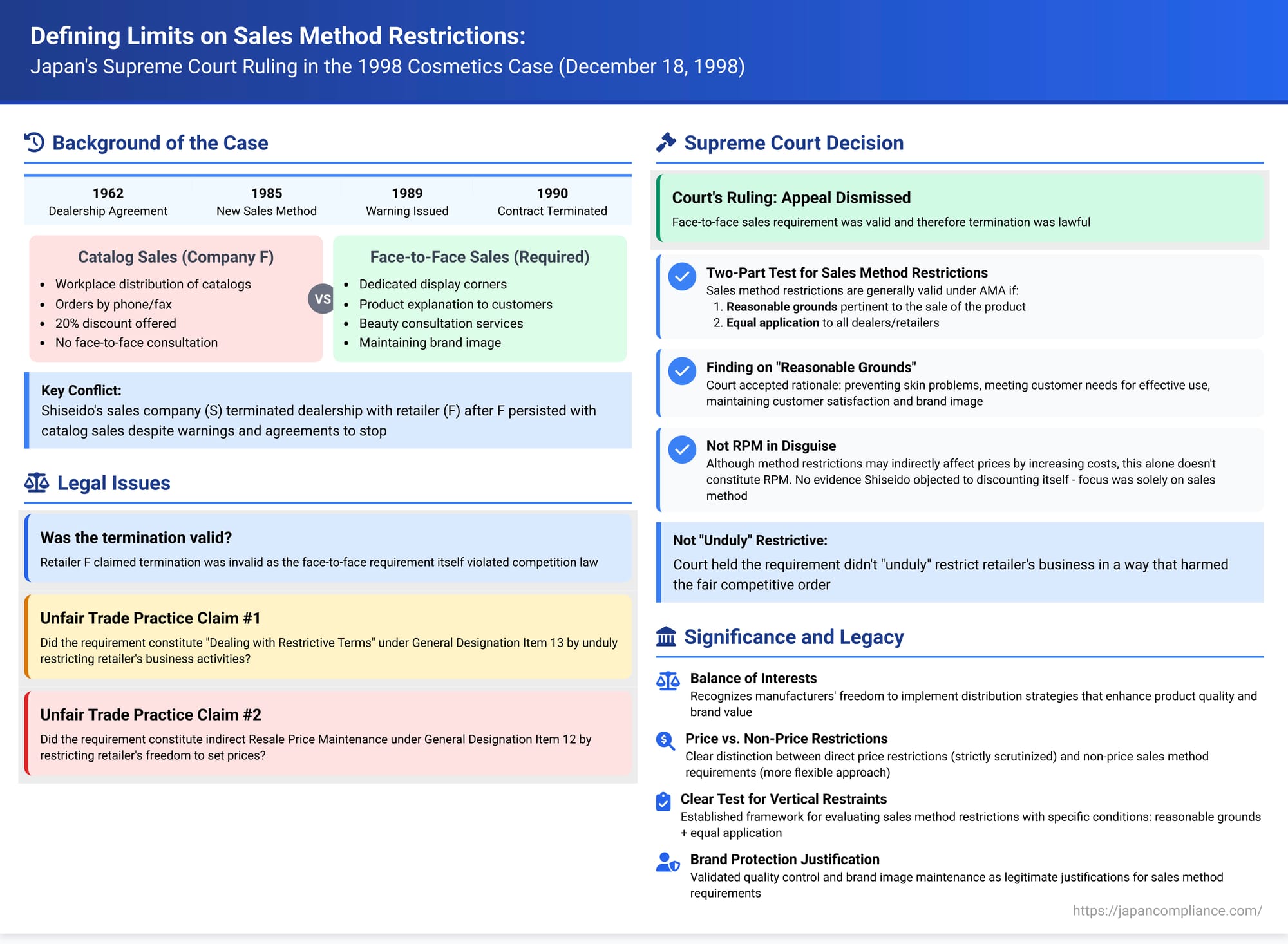

Defining Limits on Sales Method Restrictions: Japan's Supreme Court Ruling in the 1998 Cosmetics Case

Decision Date: December 18, 1998 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

Introduction

On December 18, 1998, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant ruling in a case involving Shiseido Co., Ltd., Japan's largest cosmetics manufacturer at the time, and one of its affiliated sales companies. The case centered on the legality, under Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA), of requiring authorized retailers to engage in face-to-face counseling and sales (taimen hanbai) and the subsequent termination of a long-standing dealership agreement when a retailer failed to comply with this requirement. This judgment provides important guidance on how non-price vertical restraints, specifically restrictions on sales methods, are evaluated under Japanese competition law.

Factual Background

The dispute involved Company S, a sales company specializing in cosmetics manufactured by Shiseido Co., Ltd., and Company F, a retailer engaged in the sale of cosmetics. Company S and Company F had a business relationship governed by a dealership agreement (specifically, a "Shiseido Chain Store Agreement") dating back to 1962, under which S continuously supplied F with Shiseido cosmetics.

Key elements of the relationship and the dispute include:

- The Dealership Agreement: The standard agreement used by Company S with its retailers, including Company F, contained several obligations for the dealer:

- Setting up dedicated display corners for Shiseido products.

- Attending beauty seminars organized by Company S.

- Crucially, engaging in face-to-face counseling/sales (taimen hanbai). This involved explaining product usage to customers and providing consultations regarding the cosmetics. The agreement essentially required retailers to offer (or at least be prepared to offer) this counseling service.

- The agreement had a one-year term with automatic renewal unless objected to by either party. It also included a termination clause allowing either party to terminate the agreement mid-term with 30 days' written notice.

- Company S's Rationale for Taimen Hanbai: Company S justified the requirement for face-to-face counseling based on several reasons:

- To prevent potential skin problems arising from improper cosmetic use.

- To emphasize that selling cosmetics involves selling the function of achieving beauty, not just a physical product, making instruction on proper usage essential.

- To meet customer demands for achieving enhanced beauty effects through optimal cosmetic use.

- Ultimately, to maintain customer satisfaction and trust in the distinct Shiseido brand image.

- Actual Sales Practices: While the Court acknowledged that some Shiseido cosmetics were purchased by customers without receiving counseling, a substantial volume was sold through authorized dealers who maintained dedicated corners and provided face-to-face consultations and explanations.

- Company F's Non-Compliant Sales Method: Around February 1985, Company F began employing a different sales method it termed "workplace sales" (shokuiki hanbai). This involved distributing basic catalogs (listing only product name, price, and code) to workplaces, taking bulk orders via telephone or fax, and delivering the products. Crucially, this method offered a 20% discount on the cosmetics and did not involve any face-to-face interaction, consultation, or detailed explanation beyond potentially answering questions over the phone. Company F used this method to sell various cosmetics, including those supplied by Company S.

- Discovery and Escalation: Company S discovered F's workplace sales method in late 1987.

- Initially, S requested F to remove Shiseido products from its general workplace catalog, which F did.

- However, S later found that F was using a separate, Shiseido-only catalog for the same purpose.

- In April 1989, S issued a formal written warning ("Correction Recommendation") to F, stating that the workplace sales method violated the dealership agreement's provisions requiring face-to-face counseling.

- Following negotiations between the parties' lawyers, F signed an agreement in September 1989, promising to cease catalog-based sales of Shiseido products and to conduct sales in a manner consistent with the dealership agreement terms.

- Importantly, throughout this period of negotiation and warning, Company S never raised an issue with Company F's practice of offering discounts on the products. The focus was solely on the method of sale.

- Termination of the Agreement: Despite the September 1989 agreement, Company F showed no indication of changing its sales practices. Concluding that F had no intention of complying with the taimen hanbai requirement, Company S invoked the termination clause in the dealership agreement and formally terminated the contract effective April 25, 1990, ceasing all shipments to F.

Procedural History and Legal Issues

Company F sued Company S, challenging the validity of the termination. F sought confirmation of its ongoing status as an authorized dealer entitled to receive product deliveries and demanded specific performance for products already ordered.

The trial court initially ruled in favor of Company F, finding the termination invalid largely because the taimen hanbai requirement itself might conflict with the spirit of the Antimonopoly Act by potentially aiming at price maintenance. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this decision, finding the termination valid because F had clearly breached the contractual obligation regarding sales methods. Company F appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

Before the Supreme Court, a key legal issue was whether the contractual requirement for taimen hanbai constituted an "unfair trade practice" prohibited by AMA Article 19. Specifically, Company F argued that the requirement fell under:

- General Designation Item 13 (Dealing with Restrictive Terms): Arguing it unduly restricted the retailer's freedom in its business activities. (This corresponds to Item 12 in the current General Designation).

- General Designation Item 12 (Resale Price Maintenance): Arguing it indirectly restricted the retailer's freedom to determine sales prices. (This corresponds to conduct now specified directly in AMA Article 2(9)(iv)).

Supreme Court's Analysis

The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision, finding the taimen hanbai requirement and the subsequent contract termination to be lawful under the AMA.

Issue 1: Taimen Hanbai as "Dealing with Restrictive Terms" (General Designation Item 13)

Legal Framework: The Court first outlined the relevant law. AMA Article 19 prohibits unfair trade practices. Among these, Article 2(9)(iv) (now Art. 2(9)(vi)(b)) lists conduct involving trading with a counterparty under conditions that unduly restrict the counterparty's business activities, posing a risk of impeding fair competition, as designated by the JFTC. General Designation Item 13 (now 12) specified "Dealing with the counterparty by imposing conditions that unduly restrict transactions between the counterparty and its trading partners or otherwise restrict the counterparty's business activities."

Rationale for Regulation: The Court noted that such restrictive conditions are regulated because they can artificially impede the competitive process, which should ideally function through businesses offering better quality goods and services at lower prices. Imposing restrictions, especially on the counterparty's dealings with third parties that directly affect competition, is particularly problematic.

The "Unduly Restrictive" Standard: The Court emphasized that not all restrictions are illegal. The analysis hinges on whether the restriction is "unduly" restrictive. This determination requires assessing the nature, degree, and context of the restriction to see if it genuinely risks harming the fair competitive order. Only when such a risk is identified does the condition become "unduly" restrictive.

Freedom in Sales Policy: The Court explicitly recognized that manufacturers and wholesalers should, in principle, have the freedom to choose their sales policies and methods. Therefore, imposing restrictions on retailers regarding sales methods – such as requiring product explanations, mandating quality control standards, or dictating display methods – is generally not considered "unduly" restrictive and harmful to competition provided two conditions are met:

- (a) Reasonable Grounds: The restriction must be based on "reasonable grounds pertinent to the sale of the product" (tōgai shōhin no hanbai no tame no sore nari no gōriteki na riyū).

- (b) Equal Application: The same restriction must be imposed equally on the supplier's other trading partners.

If these two conditions are satisfied, the restriction itself is unlikely to adversely affect the fair competitive order and thus does not fall under General Designation Item 13. The commentary clarifies that this framework largely follows the JFTC's Distribution Systems and Business Practices Guidelines (Ryūtsū Torihiki Kankō Gaidorain) applicable at the time, although the judgment added the nuanced phrase "sore nari no" (reasonable enough or pertinent) to the reasonableness requirement. This doesn't necessarily mean any business reason suffices; the court's analysis and the guidelines link reasonableness to factors like product safety, quality maintenance, and brand reputation – aspects connected to the competitive process and consumer benefit.

Applying the Standard to Taimen Hanbai:

- (a) Reasonable Grounds: The Court accepted Company S's justification for requiring taimen hanbai. The goal was to meet customer needs for effective cosmetic use, prevent skin trouble, and thereby maintain customer satisfaction and trust in the Shiseido brand image. Given that customer trust is crucial for competitiveness in the cosmetics market, the Court found this rationale to be reasonably grounded ("sore nari no gōrisei ga aru").

- (b) Equal Application: The Court noted that Company S used the same dealership agreement terms, including the taimen hanbai clause, with its other retailers, and that a significant amount of Shiseido cosmetics were indeed sold via this method.

Conclusion on Item 13: Since both conditions were met, the Court concluded that imposing the taimen hanbai obligation on Company F did not constitute an "unduly" restrictive condition under General Designation Item 13.

Issue 2: Taimen Hanbai as Indirect Resale Price Maintenance (General Designation Item 12)

Legal Framework: General Designation Item 12 (related to conduct now covered by AMA Art. 2(9)(iv)) prohibited, without justifiable grounds, "causing the counterparty to maintain the sales price of the goods that the designating party determines, or otherwise restricting the counterparty's free determination of sales prices". The Court acknowledged that if a restriction on sales methods is demonstrably used as a means to achieve RPM, it could be illegal from that perspective.

Analysis:

- Indirect Effect vs. RPM: The Court reasoned that while imposing specific sales methods might increase a retailer's costs, potentially leading to some stabilization of retail prices, this indirect effect alone does not automatically equate to a restriction on the free determination of sales prices (i.e., RPM).

- No Evidence of RPM Purpose: The Court affirmed the High Court's factual finding that Company S was not using the taimen hanbai requirement as a tool to enforce resale prices. The evidence, including the fact that S did not challenge F's discounting during their dispute, supported the conclusion that the termination was genuinely motivated by F's breach of the sales method requirement, not its pricing policy.

Conclusion on Item 12: Therefore, the taimen hanbai obligation did not constitute RPM under General Designation Item 12.

Validity of the Contract Termination

Having found the taimen hanbai clause itself lawful under the AMA, the Court briefly addressed the termination's validity under contract law principles. It affirmed the High Court's findings that:

- The termination was based on F's breach of the valid taimen hanbai requirement, not its discounting.

- Given F's persistent refusal to comply with the sales method requirement despite warnings and a specific agreement to do so, Company S's invocation of the contractual termination clause was not a violation of the principle of good faith (shingi-soku) nor an abuse of rights (kenri no ran'yō).

Conclusion and Significance

The Supreme Court dismissed Company F's appeal, solidifying the legality of Company S's actions. This 1998 Shiseido case (along with a similar ruling involving Kao Corporation issued the same day) provides critical precedent on the assessment of non-price vertical restraints under Japanese competition law.

The key takeaways are:

- Framework for Sales Method Restrictions: Restrictions on a retailer's sales methods imposed by a supplier are generally permissible under the AMA's prohibition on restrictive conditions if they are (a) based on reasonable grounds pertinent to the product's sale (often related to quality, safety, or brand image) and (b) applied non-discriminatorily to all dealers.

- Distinction from RPM: Such restrictions are not automatically considered RPM simply because they might increase retailer costs or indirectly stabilize prices. A clear link or intent to restrict pricing freedom must be established.

- Supplier Freedom: The ruling underscores a degree of freedom for manufacturers and suppliers in designing their distribution strategies, provided the restrictions serve legitimate purposes related to the product and competition, and are not merely arbitrary or a pretext for controlling resale prices or otherwise harming competition unduly.

This case illustrates the balancing act in competition law between protecting the business freedom of distributors and allowing suppliers to implement distribution strategies that can enhance brand value, ensure product quality, and provide consumer benefits, as long as they do not unduly harm the competitive process.