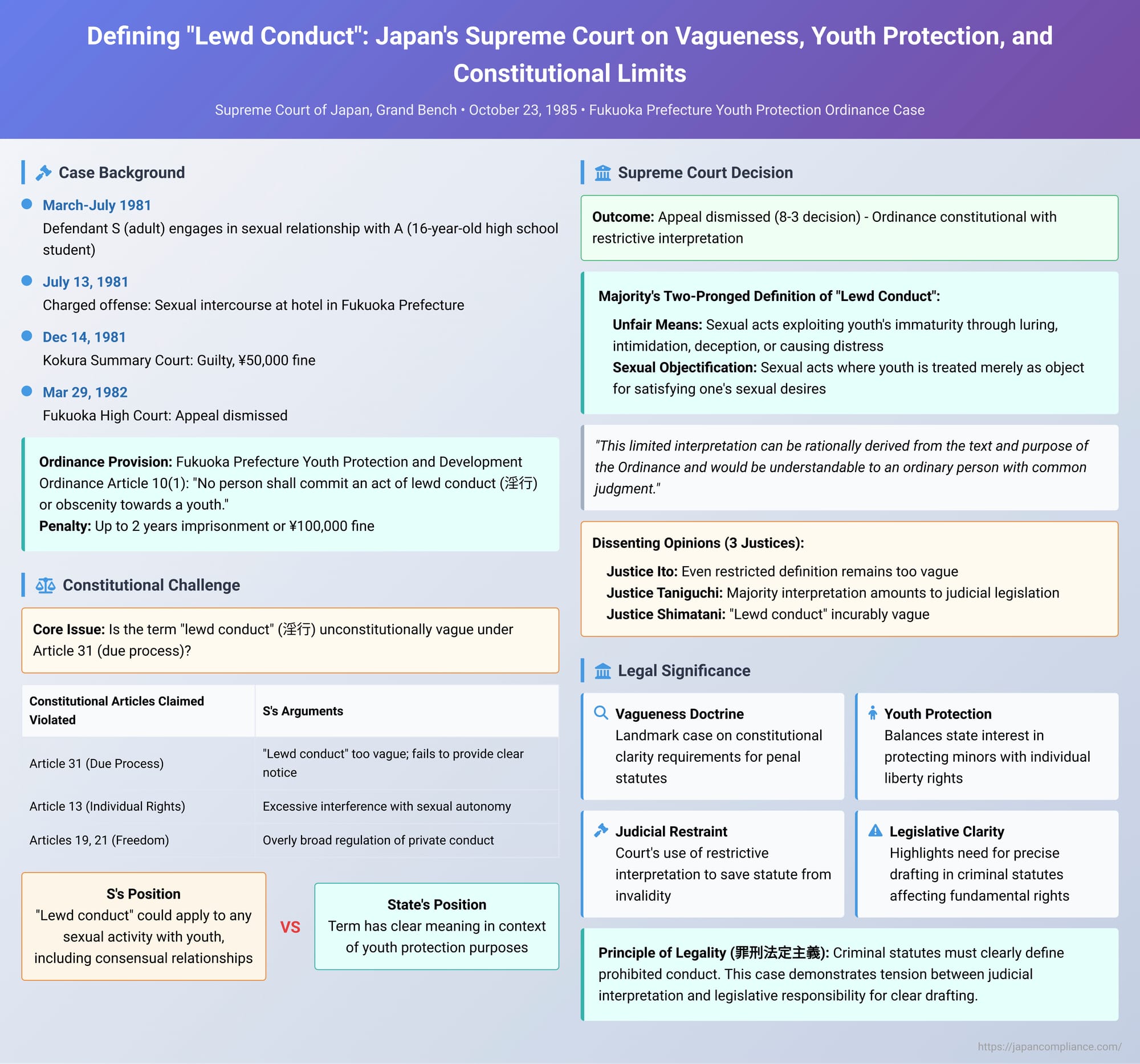

Defining "Lewd Conduct": Japan's Supreme Court on Vagueness, Youth Protection, and Constitutional Limits

Date of Judgment: October 23, 1985

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Case Name: Fukuoka Prefecture Youth Protection and Development Ordinance Violation Case

Case Number: 1957 (A) No. 621

I. Introduction: The Ordinance, "Lewd Conduct," and a Constitutional Test

On October 23, 1985, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision concerning the Fukuoka Prefecture Youth Protection and Development Ordinance. The case revolved around the prosecution of a man, S, for engaging in "lewd conduct" (inkō) with a 16-year-old girl. Beyond the specific facts, the judgment grappled with fundamental constitutional issues: the clarity required of penal statutes, the extent to which laws can regulate private sexual behavior in the name of youth protection, and the delicate balance between legislative power and judicial interpretation. At its heart, the case questioned whether the term "lewd conduct," as used in the ordinance, was unconstitutionally vague or overly broad, thereby violating Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution, which guarantees due process of law.

II. The Accusation and the Ordinance

The defendant, S, was charged under Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Fukuoka Prefecture Youth Protection and Development Ordinance (hereafter, "the Ordinance"). This provision stated: "No person shall commit an act of lewd conduct (inkō) or obscenity towards a youth." A "youth," according to Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the Ordinance, was defined as any person from the commencement of elementary school age until reaching 18 years of age, excluding those who possessed the same legal capacity as adults under other laws (e.g., married minors). Violations were punishable under Article 16, Paragraph 1 with imprisonment for up to two years or a fine of up to 100,000 yen. The Ordinance also stipulated in Article 17 that if the violator was themselves a youth, the penal provisions would not apply.

The prosecution stemmed from S's relationship with A, a girl born on July 1, 1965. The specific offense occurred on July 13, 1981, when A was 16 years old. The first instance court found that S, knowing A was a youth under 18, had sexual intercourse with her in a hotel room in Fukuoka Prefecture, thereby committing "lewd conduct."

Further details emerged at the appellate stage. S had first met A in late March 1981, shortly after she had graduated from junior high school. Aware of her age, he invited her for a drive and initiated sexual intercourse in his parked car. This encounter was the first of at least fifteen such instances leading up to the charged offense. Their meetings were reportedly focused solely on sexual activity, with no discussions of marriage or a deeper relationship. At the time of the charged incident, A was 16 and a first-year high school student.

III. Lower Court Decisions

The Kokura Summary Court, serving as the court of first instance, found S guilty of violating the Ordinance and imposed a fine of 50,000 yen on December 14, 1981. S appealed this decision.

The Fukuoka High Court, on March 29, 1982, dismissed S's appeal. The High Court affirmed the lower court's findings, emphasizing that S had treated A merely as an object for the gratification of his own sexual desires. This characterization of S's conduct became a pivotal point in the subsequent Supreme Court deliberations.

IV. The Constitutional Challenge at the Supreme Court

S appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the relevant provisions of the Fukuoka Ordinance (Articles 10(1) and 16(1)) were unconstitutional. He contended that these provisions violated several articles of the Constitution, including:

- Article 11 (guarantee of fundamental human rights).

- Article 13 (respect for the individual and the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness).

- Article 19 (freedom of thought and conscience).

- Article 21 (freedom of assembly, association, speech, press, and all other forms of expression).

- Most significantly, Article 31 (due process of law), which is understood in Japanese jurisprudence to encompass the principle that penal statutes must be clear and not overly broad.

The core of S's constitutional challenge was that the term "lewd conduct" (inkō) was excessively vague, failing to provide clear notice of what actions were prohibited. This vagueness, he argued, meant the Ordinance could be applied to a wide array of conduct, including consensual sexual activity between older youths or those in genuine romantic relationships, thus making the scope of punishment unreasonably broad.

V. The Supreme Court's Majority Opinion: A Restrictive Interpretation to Save the Ordinance

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court ultimately dismissed S's appeal, upholding the constitutionality of the Ordinance provisions, but only by significantly narrowing the interpretation of "lewd conduct."

The majority opinion began by acknowledging the purpose of the Ordinance: to promote the sound development of youths by protecting them from harmful influences, given their physical and mental immaturity and emotional vulnerability. Sexual acts, the Court noted, can inflict significant psychological harm on youths, from which recovery can be difficult. The Ordinance, therefore, aimed to prohibit sexual acts directed at youths that could impede their healthy development and are generally condemned by societal norms.

To address the concerns of vagueness and overbreadth, the Court declared that "lewd conduct" under Article 10, Paragraph 1 should not be interpreted as encompassing all sexual acts with youths. Such a broad interpretation, the majority reasoned, would not only deviate from the inherent meaning of "lewd" (in) in "lewd conduct" (inkō), which implies something illicit or immoral, but would also criminalize acts generally considered outside the scope of punishment, such as those between youths in a betrothed relationship or a similarly serious romantic commitment. Furthermore, merely defining "lewd conduct" as "immoral" or "impure" sexual acts would be too indefinite to serve as a clear standard for criminal liability.

Instead, the Supreme Court offered a two-pronged restrictive definition of "lewd conduct":

- Sexual intercourse or similar acts performed by taking advantage of the youth's physical or mental immaturity through unfair means such as luring, intimidation, deception, or causing the youth distress or confusion.

- Sexual intercourse or similar acts where it can only be recognized that the youth is being treated merely as an object for satisfying one's own sexual desires.

The Court asserted that this limited interpretation could be rationally derived from the text and purpose of the Ordinance and would be understandable to an ordinary person with common judgment. With "lewd conduct" thus defined, the majority concluded that the Ordinance provisions were neither unconstitutionally vague nor overly broad in their scope of punishment. Consequently, they did not violate Article 31 of the Constitution. The claims based on Articles 11, 13, 19, and 21 were also dismissed as lacking foundation once the primary Article 31 challenge failed.

Applying this interpretation to S's specific case, the Court reviewed the facts established by the lower courts: the respective ages of S and A, the circumstances leading to their sexual relationship, and the overall nature of their interactions. Based on these factors, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts' finding that S had indeed treated A merely as an object for his sexual gratification. Therefore, S's actions fell within the second prong of the newly articulated definition of "lewd conduct," and the lower court's judgment was deemed correct.

The Court also addressed and dismissed S's other constitutional arguments, such as claims of unequal treatment under Article 14 due to regional variations in youth protection ordinances, alleged age discrimination, the ordinance purportedly exceeding the scope of national law (Article 94), and the ordinance being a special law requiring a local referendum under Article 95.

VI. Concurring Voices: Supplementary Opinions

Two Justices provided supplementary opinions, concurring with the majority's conclusion and its restrictive interpretation of "lewd conduct."

One supplementary opinion underscored the significant disparities and lack of uniformity among youth protection ordinances across different prefectures. It argued that this situation, while not necessarily violating Article 14 (equality under the law), was undesirable for a national legal system. Consequently, a cautious and restrictive approach to interpreting "lewd conduct" provisions was warranted, limiting punishable acts to those that would find a consensus of condemnation among the majority of citizens nationwide. This Justice found the majority's two-pronged definition appropriate, specifically affirming that treating a youth merely as an object for sexual gratification—typified by casual encounters where the youth is exploited—is widely considered reprehensible and deserving of punishment. Such an interpretation, it was argued, did not stray too far from the ordinary meaning of "lewd conduct" and was consistent with the ordinance's protective aims.

The other supplementary opinion also endorsed the majority's definition. It elaborated that "lewd conduct" is a normative legal concept requiring a value judgment based on prevailing societal norms at the time of the act. For such normative elements to satisfy the clarity requirement, it must be possible for an ordinary person, guided by societal norms, to discern what conduct is punishable. This opinion discussed the relationship between the Ordinance and national laws like the Penal Code (which addresses offenses like rape) and the Child Welfare Act. It viewed the Ordinance as supplementing these national laws by targeting acts that exploit the immaturity of youths, even if such acts don't meet the criteria for crimes under national statutes. The age threshold of 18 for "youth" was deemed a matter of reasonable legislative discretion. It also acknowledged that while this restricts the sexual freedom of youths, prioritizing their protection from the potential negative impacts of sexual experiences, given their general immaturity in judgment, is a permissible legislative policy.

VII. Dissenting Voices: Concerns over Vagueness and Judicial Overreach

Three Justices dissented, expressing strong reservations about the majority's approach and the constitutionality of the Ordinance provision.

Justice Ito, in his dissent, agreed with the majority's intent to limit the scope of "lewd conduct" to prevent arbitrary application. However, he found the majority's solution inadequate. He argued that the second prong of the majority's definition—"treating the youth merely as an object for satisfying one's own sexual desires"—remained problematic in terms of clarity and was not an appropriate criterion for limiting the scope of punishment, especially considering its relationship with national law. More fundamentally, Justice Ito doubted whether an ordinary person could reasonably derive either of the majority's interpretive prongs from the simple term "lewd conduct" (inkō). He favored an even narrower interpretation, suggesting that only acts involving "unfair means" (similar to the majority's first prong) could potentially be considered, but ultimately concluded that even this was an untenable stretch of the term's meaning. Therefore, he found the term "lewd conduct" incurably vague and the Ordinance provision unconstitutional under Article 31. Justice Ito also highlighted the significant and problematic lack of uniformity in how different prefectural ordinances addressed "lewd conduct," which he felt undermined the rationality of the legal framework.

Justice Taniguchi's dissent argued that the majority's restrictive interpretation went beyond the legitimate bounds of judicial interpretation and amounted to judicial legislation, which is improper. He asserted that the term "lewd conduct" itself inherently lacked the clarity required for a criminal statute. Furthermore, Justice Taniguchi contended that Article 31 of the Constitution encompasses a principle of "substantive due process" or "appropriate punishment." From this perspective, he argued that uniformly criminalizing all sexual acts with older youths (specifically those 16 years of age and older, who have the legal capacity to marry under the Civil Code, albeit with parental consent if minors) was an excessive and unconstitutional infringement on personal liberty. He suggested that for sexual acts with older youths to be punishable, additional elements demonstrating clear illegality (such as the use of unfair means) would need to be explicitly part of the offense.

Justice Shimatani, in a separate dissent, also found the term "lewd conduct" to be excessively vague and therefore unconstitutional under Article 31. He criticized the majority's attempt to salvage the provision through restrictive interpretation, stating that the interpretation offered went far beyond what an ordinary person could possibly understand from the word "lewd conduct." He emphasized that criminal statutes must clearly inform citizens of prohibited conduct, a function that a vague term like "lewd conduct" fails to fulfill.

VIII. The Constitutional Crucible: Clarity, Due Process, and Penal Law in Japan

This case brought to the forefront key principles of Japanese constitutional and criminal law, particularly those flowing from Article 31's due process guarantee. These include:

- The Principle of Legality (罪刑法定主義 - Zaikyōhōteishugi): This is a cornerstone of modern criminal justice, demanding that crimes and punishments be clearly defined by law. Several sub-principles emanate from it:

- Requirement of Clarity/Definiteness (明確性の原則 - Meikakusei no Gensoku): Penal statutes must be drafted with sufficient clarity so that individuals can understand what conduct is prohibited. This is often referred to as the "void-for-vagueness" doctrine. The leading Japanese case on this, the 1975 Tokushima City Public Safety Ordinance decision, established the standard: a penal statute is unconstitutionally vague if an ordinary person of common intelligence cannot determine from its language whether their conduct would fall within its scope. Despite this standard, the Japanese Supreme Court has rarely invalidated statutes on vagueness grounds.

- Prohibition of Overly Broad Penal Statutes (過度広汎性の原則 - Kado Kōhansei no Gensoku): A law must not be so broad as to sweep within its ambit constitutionally protected conduct or a range of innocent activities far beyond what is necessary to achieve its legitimate purpose.

- Principle of Appropriate Punishment / Substantive Due Process (適正処罰の原則 - Tekisei Shobatsu no Gensoku): This principle, which some dissents explicitly linked to Article 31, suggests that the substance of a penal law must be reasonable and not impose punishments that are grossly disproportionate or unduly infringe upon fundamental rights. The Sarufutsu case (1974) and later cases like the Hiroshima City Bōsōzoku Expulsion Ordinance case (2007) have touched upon this, evaluating regulations based on their purpose, rationality, and balance of interests.

The Fukuoka Ordinance case highlighted the inherent tension between the state's legitimate interest in protecting vulnerable youths and the individual's right to liberty and clear notice of what the law proscribes. The majority sought to resolve this tension through restrictive interpretation (限定解釈 - gentei kaishaku), a common judicial technique where courts narrow the scope of broadly worded statutes to bring them into conformity with constitutional requirements. However, this practice itself raises questions about the separation of powers: how far can the judiciary go in "rewriting" or "curing" a vague statute before it encroaches upon the legislative domain? The dissenting opinions, particularly Justice Taniguchi's, voiced strong concerns about this very issue.

IX. "Lewd Conduct" (Inkō): A Term Laden with Ambiguity

The term "lewd conduct" (inkō) proved to be the linchpin of the constitutional debate. Its inherent ambiguity presents a significant challenge for legal definition. The characters forming the word – 淫 (in, meaning lewd, licentious, excessive) and 行 (kō, meaning act, conduct) – suggest a type of behavior that is morally disapproved of, but translating this into a precise legal standard is fraught with difficulty.

The majority's two-pronged definition was an attempt to inject concreteness into this nebulous term. The first prong, focusing on "unfair means" that exploit a youth's immaturity (luring, intimidation, deception, etc.), offers relatively objective criteria. However, the second prong—"treating the youth merely as an object for satisfying one's own sexual desires"—drew considerable criticism, both from the dissenting Justices and in subsequent legal commentary. Critics argued that this standard is itself vague, relying heavily on subjective judgments about the nature of a relationship and the motivations of the individuals involved. It risks veering into the "enforcement of morals" by the criminal law, punishing relationships deemed insufficiently "genuine" or "loving," which is generally considered problematic from a liberal legal perspective.

The problem was compounded by the lack of national uniformity. As Justice Ito's dissent detailed, prefectural ordinances across Japan exhibited wide variations in whether and how they regulated "lewd conduct," the definitions employed, and the penalties imposed. This inconsistency raised questions about fairness and the rationality of the overall legal landscape concerning youth protection.

X. Concluding Reflections: Judicial Power, Legislative Responsibility, and the Rule of Law

The Supreme Court's 1985 decision in the Fukuoka Prefecture Youth Protection and Development Ordinance case remains a significant judgment in Japanese constitutional law concerning the clarity of penal statutes. It showcases the Court's tendency to employ restrictive interpretation to uphold the constitutionality of laws, rather than striking them down for vagueness – a practice that has been both praised for its judicial restraint and criticized for potentially papering over legislative deficiencies.

The sharply divided opinions within the Grand Bench highlight the profound disagreements over the judiciary's proper role in such cases. Should courts actively "cure" vaguely drafted laws to make them constitutional, or should they invalidate such laws, thereby compelling legislatures to draft clearer and more precise statutes? The latter approach would place a stronger emphasis on the legislative branch's primary responsibility for defining criminal conduct in a manner that respects the principle of legality and provides clear guidance to citizens.

Ultimately, the case underscores the enduring tension between the societal imperative to protect vulnerable groups like youths and the fundamental principles of criminal justice that safeguard individual liberty. It serves as a potent reminder of the critical importance of clear legislative drafting, especially in the realm of penal law, where the power of the state is brought to bear most forcefully upon the individual. The debate over what constitutes "lewd conduct" and how it should be regulated continues to resonate, reflecting evolving societal norms and the ongoing quest for a just and clear legal framework.