Defining "Known Creditors" in Corporate Capital Reductions: A 1932 Japanese Precedent

Judgment Date: April 30, 1932

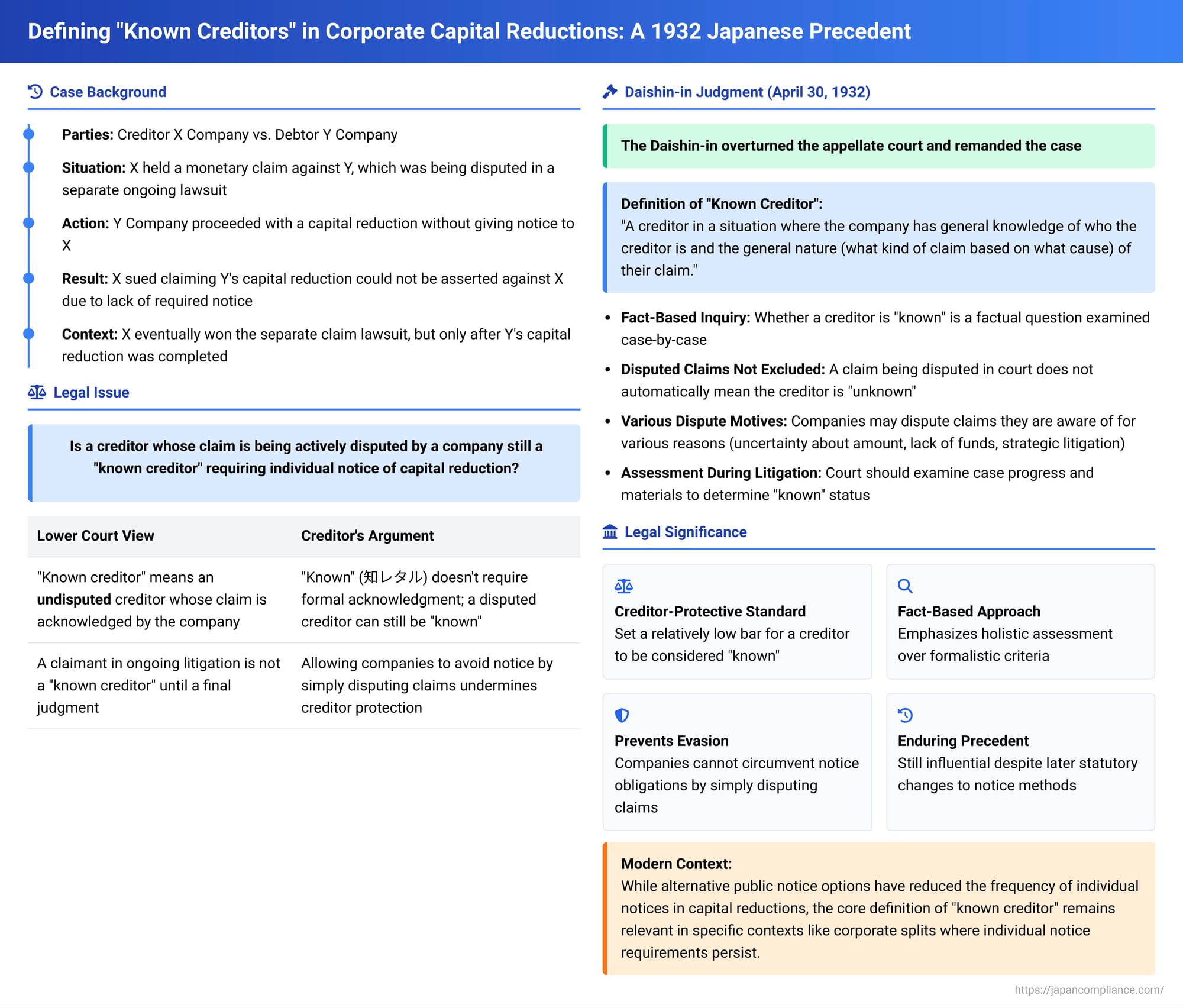

When a company undertakes significant structural changes, such as a reduction in its capital, the law mandates procedures to protect the interests of its creditors. A crucial aspect of these procedures has historically been the requirement for the company to give individual notice to its "known creditors," allowing them an opportunity to object. A seminal decision by the Daishin-in (Japan's Supreme Court before the current Constitution) on April 30, 1932, in the "Capital Reduction Non-Assertability Confirmation Claim Case," delved into the definition of a "known creditor," particularly when the creditor's claim was actively being disputed by the company. This ruling, despite its age, remains a foundational piece of jurisprudence in Japanese corporate law.

Factual Background: A Disputed Debt and a Capital Reduction

The case involved two companies: X Company (the plaintiff creditor) and Y Company (the defendant debtor). X Company held a monetary claim against Y Company. While this claim was the subject of a separate, ongoing lawsuit initiated by X Company to demand payment, Y Company proceeded with a resolution to reduce its capital.

Under the Commercial Code provisions applicable at the time (specifically Article 78, which has parallels with Article 449, Paragraph 2 of the current Companies Act concerning creditor objection procedures), companies reducing their capital were required to provide individual notice (a formal call or saikoku) to their "known creditors." Y Company, however, carried out its capital reduction and registered it without providing such individual notice to X Company.

Consequently, X Company filed another lawsuit – the one leading to this Daishin-in decision. X Company sought a court confirmation that Y Company's capital reduction could not be asserted against X Company due to the failure to provide notice. This was based on Article 80 of the then-Commercial Code (related to Article 449, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, though the legal effect of non-compliance later shifted from the capital reduction being "non-assertable" against the unnotified creditor to the creditor being able to "dispute the invalidity" of the reduction in a 1938 amendment ).

A critical fact was that the separate lawsuit concerning X Company's underlying claim against Y Company was only finalized—with X Company ultimately winning—after the period for Y Company's creditors to object to the capital reduction had already expired.

Y Company's defense against X Company's claim (that the capital reduction was non-assertable) hinged on the argument that X Company was not a "known creditor" at the time of the capital reduction process. Y Company contended that because the claim was actively being disputed in court, it did not fall under the category of claims held by "known creditors" requiring individual notice.

The court of first instance found in favor of X Company. However, the appellate court reversed this decision, siding with Y Company. The appellate court held that a "known creditor" for the purposes of this notice requirement must be one whose claim is clear and undisputed by the debtor company. Since X Company's claim was under litigation, X Company was deemed not to be a "known creditor."

X Company appealed to the Daishin-in, arguing that:

- The term "known" (知レタル - shiretaru) creditor does not equate to the company having formally acknowledged the debt.

- The appellate court's interpretation—that a company can simply dispute a claim to avoid the notice obligation—undermines the legislative intent of creditor protection.

The Daishin-in's Landmark Definition of a "Known Creditor"

The Daishin-in, in its judgment of April 30, 1932, overturned the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court provided a clear and enduring definition of a "known creditor":

A "known creditor" (知レタル債権者 - shiretaru saikensha) is a creditor in a situation where the company has general knowledge of who the creditor is and the general nature (what kind of claim based on what cause) of their claim.

The Daishin-in further elaborated:

- Factual Inquiry: Whether a creditor is "known" is a question of fact to be determined by examining all relevant circumstances in each individual case.

- Disputed Claims Are Not Automatically Excluded: Critically, the Court stated that even if a company is actively disputing a claim asserted against it in a lawsuit, this does not necessarily mean that the claimant is not a "known creditor" until a final judgment is rendered against the company.

- Assessment During Pending Litigation: It is possible to determine that a litigating claimant is a "known creditor" even while the lawsuit is still pending. This determination should be made by investigating the progress of the case, the litigation materials already presented, and other various circumstances.

- Companies Dispute Claims for Various Reasons: The Daishin-in reasoned that a company might dispute a creditor's claim for several reasons. It could be because the company genuinely believes the claim is non-existent. However, a company might also dispute a claim even if it is generally aware of it but is uncertain about the precise scope or amount pending a court's determination. Furthermore, a company might contest a claim it fully knows to be legitimate due to a lack of funds for payment or other internal reasons. Therefore, the mere fact that a claim is being disputed is not conclusive evidence that the creditor is "unknown" to the company.

The Daishin-in found that the appellate court had erred in law by interpreting "known creditor" as requiring the claim to be clear and undisputed by the company, and by concluding that a creditor whose claim is under litigation is not a "known creditor."

Enduring Relevance and Modern Context

While this Daishin-in decision is nearly a century old, it remains a leading case on the interpretation of "known creditor." However, the legal landscape surrounding creditor protection in corporate restructuring has evolved.

Changes in Notice Requirements

A significant change occurred with amendments to the Commercial Code (prior to the current Companies Act of 2005). These reforms introduced an alternative to individual notices for capital reductions. If a company publishes a notice in the Official Gazette and also provides notice through a method stipulated in its articles of incorporation (such as a designated daily newspaper or electronic public notice), it can generally dispense with the need for individual notices to "known creditors" (this principle is found in the former Commercial Code Article 100, Paragraph 4, and influences Article 449, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act).

Consequently, the direct question of whether a creditor is "known" for the purpose of individual notice in a capital reduction now primarily arises if the company does not utilize these alternative, broader public notice methods. However, the concept of "known creditor" has not become entirely obsolete. For instance, in the context of company demergers (corporate splits), the Companies Act still explicitly requires individual notice to "known creditors" concerning tort claims against the demerging company (see Article 789, Paragraph 3, proviso, and Article 810, Paragraph 3, proviso of the Companies Act).

The Prevailing Interpretation and Its Roots

The prevailing academic view on the definition of a "known creditor" aligns with the Daishin-in's 1932 judgment. It is understood as a creditor whose identity, and the general cause and content of whose claim, are known to the company. This knowledge is often inferred from objective circumstances that should have made the company aware of the claim. Thus, even before a lawsuit regarding the claim is finalized, a creditor might be considered "known." Conversely, even if a company loses a lawsuit, if it was objectively reasonable at the time of the creditor protection procedures to believe the claim did not exist, the creditor might not have been "known" for notice purposes.

The 1932 Daishin-in judgment's definition is abstract enough that it wasn't directly invalidated by later statutory changes regarding notice methods. However, the practical context for applying this definition has shifted. Before the broader public notice options became available, interpreting "known creditor" too broadly could place a significant burden on companies undertaking restructuring. This might have led to a more restrictive interpretation to allow companies to omit individual notices in certain cases (e.g., for minor claims, or claims certain to be paid before the restructuring took effect). With the availability of alternative public notice, any assessment of "known" status in the limited scenarios where individual notice is still pivotal might be approached differently.

Broader Issue: Scope of Claims for Objection

While the specific trigger for individual notice to a "known creditor" is less frequent now, the underlying issue of the scope of claims that can entitle a creditor to object to a capital reduction (or other forms of corporate reorganization) remains highly relevant. This is because companies must document how they have dealt with any objecting creditors when they apply to register the corporate reorganization (e.g., Commercial Registry Act, Article 70). Failure to properly address valid objections can lead to administrative fines or even lawsuits seeking to nullify the entire reorganization.

If a creditor objects, the company typically must either pay the debt, provide adequate security, or entrust property of equivalent value to a trust company for the creditor's benefit. An exception exists if it can be shown that the reorganization poses no risk of harm to the creditor (e.g., if the creditor is already fully secured). This principle was explicitly included in a 1997 amendment to the Commercial Code.

The determination of what types of claims can form the basis for a valid objection is complex and involves considerations such as:

- Claims confirmed by a non-final judgment: In practice, for registration purposes, it has been suggested that the company should place the amount awarded by a non-final judgment in trust, contingent on the judgment becoming final.

- Future claims: Claims that have not yet crystallized into specific monetary amounts, such as those arising from ongoing supply contracts or employment agreements, are generally not considered valid grounds for objection by some commentators, although there are differing views and historical case law that might suggest otherwise in specific contexts.

- Non-monetary claims: There is debate as to whether only quantifiable monetary claims can be the basis for an objection, given the nature of the protective measures (payment, security). Some legal scholars and a historical Daishin-in case from 1935 (concerning an electricity supply claim) suggest that non-monetary claims could, in principle, also be grounds for objection.

Analysis and Enduring Principles

The Daishin-in's 1932 decision established a creditor-protective standard by setting a relatively low bar for a creditor to be considered "known."

- Fact-Based and Holistic Inquiry: The ruling emphasizes a holistic, fact-based assessment of the company's awareness rather than relying on a formalistic criterion like whether a claim is undisputed.

- Preventing Evasion of Notice: It prevents companies from easily circumventing their notice obligations by merely denying or disputing claims, even if such disputes are not made in good faith. The focus is on what the company generally knows or should reasonably know.

- Balancing Interests: While creditor-protective, the definition also implies that a company is not expected to give individual notice to those whose claims are genuinely unknown or so speculative that the company cannot be said to have a general awareness of them.

The current Companies Act has separate, detailed provisions for creditor protection procedures for different types of corporate actions (capital reduction, mergers, demergers, etc.), unlike the old Commercial Code which often relied on applying merger provisions mutatis mutandis. This structural change could lead to the development of nuanced interpretations specific to each type of procedure. Historically, for instance, capital reductions involving actual payouts to shareholders were sometimes viewed as having a more direct and significant impact on creditors' interests compared to other reorganizations, potentially warranting stricter adherence to notice requirements where opt-outs through newspaper announcements were not permitted.

Conclusion

The Daishin-in's 1932 ruling on "known creditors" offers a practical and enduring definition: a creditor is "known" if the company is generally aware of the creditor's identity and the broad outlines of their claim. The fact that a claim is disputed in court does not, by itself, negate the company's awareness or its obligation to treat the claimant as a known creditor if the circumstances otherwise indicate such knowledge. While statutory reforms have changed the frequency with which this specific definition is invoked for individual notice in capital reductions, the underlying principle of assessing the company's actual state of awareness remains a vital concept in the broader context of creditor protection in Japanese corporate law. It underscores that creditor rights cannot be easily dismissed through procedural maneuvers or simple denials by the debtor company.