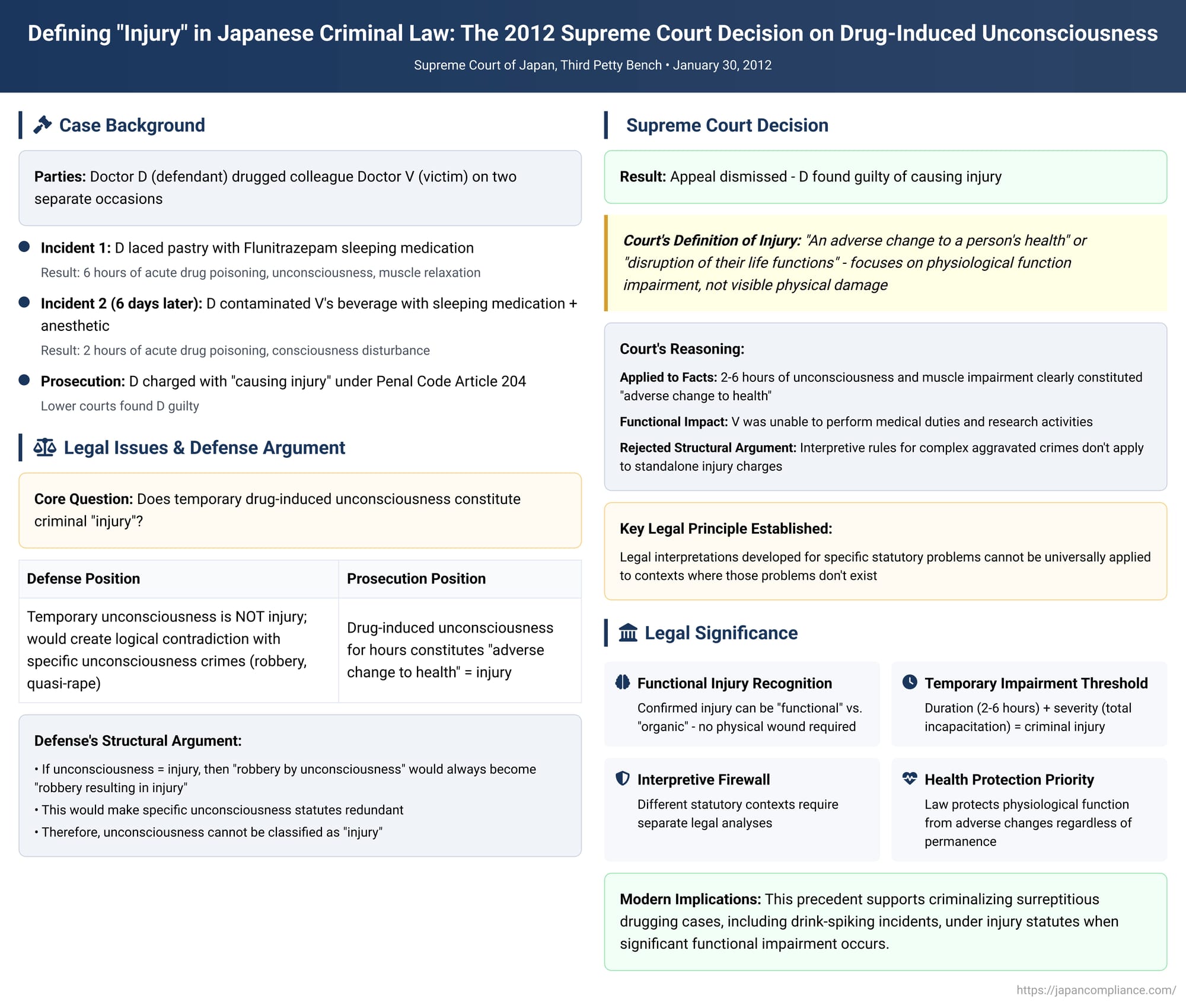

Defining "Injury" in Japanese Criminal Law: The 2012 Supreme Court Decision on Drug-Induced Unconsciousness

Case Title: Case of Causing Injury

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Decision Date: January 30, 2012

Introduction

What constitutes a criminal "injury" under the law? While a physical wound like a cut or a broken bone is straightforward, the legal boundaries become less clear when dealing with temporary, non-permanent conditions. In a significant 2012 decision, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this very issue, clarifying whether inducing a temporary state of unconsciousness and muscle impairment through surreptitious drugging qualifies as "causing injury" under the Penal Code.

The case involved a doctor who, on two separate occasions, drugged a colleague, resulting in hours-long episodes of acute drug poisoning. The defendant’s novel legal defense argued that such a temporary state, if it were considered an injury, would create a logical contradiction within the structure of Japan's Penal Code. The Supreme Court's rejection of this argument and its reaffirmation of the core principles defining "injury" provide crucial insight into the Japanese legal system's approach to bodily harm. This decision not only solidifies the legal understanding of injury but also delineates the boundaries between different, yet related, criminal offenses.

Facts of the Case

The defendant, D, and the victim, V, were both doctors affiliated with the same university hospital. The events unfolded over two separate incidents.

Incident One:

The first incident occurred while V was on holiday duty at the university hospital. D prepared a pastry laced with powdered sleeping medication containing Flunitrazepam. D then offered this pastry to V, who, unaware of its contents, consumed it. As a direct result, V fell into a state of acute drug poisoning, suffering from a disturbance of consciousness and significant muscle relaxation for approximately six hours.

Incident Two:

Six days later, D struck again. V was in a research laboratory at the hospital, engaged in medical research. V had a partially consumed canned beverage on a desk. Seizing the opportunity, D adulterated the drink with a similar sleeping medication powder, this time also adding an anesthetic. V later drank the contaminated beverage, again without any knowledge of its contents. This led to a second bout of acute drug poisoning, with symptoms of disturbed consciousness and muscle relaxation lasting for about two hours.

In both instances, V’s ability to function was severely impaired, though the effects were temporary and did not result in permanent organic damage. The lower courts, both the District Court and the High Court, found that D's actions constituted the crime of causing injury under Article 204 of the Penal Code of Japan. D appealed this verdict to the Supreme Court.

The Defendant's Argument: A Structural Conundrum

The defendant’s appeal to the Supreme Court was not a simple denial of the facts. Instead, the defense constructed a sophisticated legal argument based on the internal logic and structure of the Penal Code. The core of this argument rested on the relationship between the general crime of "causing injury" (傷害罪, shōgai-zai, Article 204) and other, more complex offenses.

The defense's argument proceeded in the following steps:

- Uniform Definition of "Injury": The defense began by asserting that, according to established case law and prevailing legal theory, the definition of "injury" is consistent across the Penal Code. That is, what constitutes an "injury" for the crime of robbery-resulting-in-injury should be the same as what constitutes an "injury" for the standalone crime of causing injury.

- The Existence of Specific "Unconsciousness" Crimes: The defense then pointed to two specific types of crimes in the Penal Code:

- Robbery by Causing Unconsciousness (昏睡強盗罪, konsui-gōtō-zai, Article 239): This crime punishes robbery committed by making the victim unconscious (e.g., through drugs).

- Quasi-Rape by Causing Loss of Mind (準強制性交等罪, jun-kyōsei-seikō-tō-zai, Article 178, Paragraph 2): This provision criminalizes sexual intercourse with a person by taking advantage of their state of unconsciousness or inability to resist.

- The Logical Contradiction: This led to the crux of the argument. If causing a temporary state of drug-induced unconsciousness (konsui) were legally classified as an "injury," a logical paradox would emerge.

- Every single instance of "Robbery by Causing Unconsciousness" (Art. 239) would necessarily fulfill the criteria for the more serious offense of "Robbery Resulting in Injury" (強盗致傷罪, gōtō-chishō-zai, Article 240). The act of causing the unconsciousness (the means of the robbery) would itself be the "injury."

- Similarly, every act of "Quasi-Rape" accomplished by drugging the victim into unconsciousness would automatically become "Rape Resulting in Injury" (強制性交等致傷罪, kyōsei-seikō-tō-chishō-zai, Article 181).

- Conclusion of the Defense: The defense argued that this outcome would render the specific statutes for robbery-by-unconsciousness and quasi-rape effectively redundant. The legislature must have intended for these statutes to have a distinct purpose. Therefore, to preserve the structural integrity of the Penal Code, the kind of temporary unconsciousness "contemplated" by these specific statutes should not be considered an "injury" in the legal sense. As such, the defendant argued that V's temporary symptoms did not amount to a criminal injury, and D should be acquitted of the charge under Article 204.

The Supreme Court's Ruling and Rationale

The Supreme Court unanimously decided to dismiss the appeal, upholding the guilty verdicts of the lower courts. While the technical grounds for the appeal were found to be invalid, the Court took the opportunity to address the substance of the defendant's argument ex officio (on its own authority), providing a definitive clarification of the law.

The Court’s reasoning was direct and elegantly sidestepped the complex structural trap posed by the defense.

First, the Court reiterated the long-standing judicial definition of a criminal injury. Citing precedent, it defined an injury as "an adverse change to a person's health" or a "disruption of their life functions" (被害者の健康状態を不良に変更し、その生活機能の障害を惹起した). This definition, known as the "physiological function impairment theory" (seiriteki-kinō-shōgai-setsu), focuses on the negative impact on the victim's bodily health and ability to function, rather than requiring visible physical damage.

Second, the Court applied this definition directly to the facts of the case. The defendant, by administering sleep medication and anesthetics, caused the victim to suffer from acute drug poisoning. The symptoms—a disturbance of consciousness and muscle relaxation lasting for approximately six hours in the first instance and two hours in the second—were a clear "adverse change" to the victim's health. They were also a manifest "disruption" of the victim's life functions; V was a doctor on duty and later engaged in research, activities that were rendered impossible by the induced state.

Third, and most crucially, the Court directly addressed and dismissed the defendant's central argument regarding other statutes. The Court stated:

"The interpretation concerning the relationship between crimes such as robbery by causing unconsciousness and crimes such as robbery resulting in injury, as pointed out in the argument, does not affect the disposition of the present case, in which the establishment of the crime of causing injury is at issue. It cannot be said that the establishment of the crime of causing injury is to be denied in the present case for the reasons asserted in the argument."

In this single, decisive statement, the Court severed the link the defense had tried to create. The Court's logic is that the special interpretive rules that might apply to result-based aggravated crimes (結果的加重犯, kekkateki-kajū-han), like robbery-resulting-in-injury, are not transferable to a standalone charge of causing injury. The reason one might hesitate to classify unconsciousness as an "injury" in a robbery case is to avoid a logical redundancy specific to that context. However, in a case where only injury is charged, that structural concern is absent. The only question is whether the defendant's actions caused an adverse change to the victim's health. Here, the answer was an unequivocal yes.

Legal Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's decision carries several important implications for the understanding of criminal law in Japan.

1. Reaffirmation of the "Physiological Function Impairment" Theory

The cornerstone of Japanese law on criminal injury is the "physiological function impairment theory." This stands in contrast to a "completeness impairment theory" (kanzensei-kison-setsu), which would criminalize acts that mar the body's physical integrity without necessarily harming its function, such as cutting off someone's hair. By focusing on the "adverse change in health," the Court reinforced that the essence of injury lies in the degradation of the body's ability to operate normally.

This case further clarified that an injury can be "functional" (kinō-teki-shōgai) as opposed to purely "organic" (kishitsu-teki-kison). There was no physical wound or tissue destruction. The harm was the temporary but total incapacitation of the victim’s consciousness and motor control. The Court recognized this functional impairment as a genuine injury, adding it to a list of other non-organic harms previously recognized by Japanese courts, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), general malaise from poisoning, and pain without any visible external signs.

2. The Threshold for "Transitory" Impairment

A key question is what level of temporary impairment qualifies as a criminal injury. A fleeting moment of dizziness is unlikely to suffice. Legal scholars and courts have considered two main factors in such cases: duration and severity ("depth").

Past case law has been nuanced. For example, a 1926 decision found that a 30-minute fainting spell following an assault was not an injury because the victim recovered quickly with no after-effects. However, other cases found conditions like dizziness and vomiting from nicotine poisoning to be injuries.

In the present case, both factors weighed heavily in favor of finding an injury.

- Duration: The impairment lasted for two and six hours, respectively. These are substantial periods, far exceeding a momentary lapse.

- Severity: The "depth" of the impairment was significant. The victim was not merely drowsy; V experienced a "disturbance of consciousness" and "muscle relaxation" severe enough to require being relieved from medical duties and rendering them unable to perform complex tasks. Compared to a brief fainting spell or minor擦過傷 (abrasions) that have been held to be injuries, the state induced in V was arguably much more severe.

3. The Separation of Statutory Interpretations

The most legally innovative aspect of the decision is its firewalling of legal interpretations. The Court confirmed that the logic used to interpret one set of statutes (result-based aggravated crimes) does not automatically apply to another (a simple, standalone offense).

The reason for treating unconsciousness differently in the context of a robbery-by-unconsciousness charge is to prevent the base crime from being automatically and always subsumed by the aggravated version, a principle aimed at avoiding double jeopardy for the same element and maintaining a coherent statutory hierarchy. It is a specific limiting principle for a specific legal problem.

The Supreme Court declared that this limiting principle has no place in a straightforward injury case under Article 204. In such a case, the court's task is not to navigate complex relationships between different crimes, but simply to apply the definition of injury to the facts at hand. The defendant's actions caused a serious, albeit temporary, impairment of the victim's health. That is an injury, full stop.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2012 decision in this case is a landmark clarification of the concept of "injury" in Japanese criminal law. It robustly affirms that the core of the offense is the impairment of physiological function, not necessarily the presence of a physical wound. By finding that a drug-induced state of unconsciousness lasting several hours constitutes a legally cognizable injury, the Court adapted the law to harms that are functional rather than organic.

Most significantly, the ruling provides a vital lesson in statutory interpretation. It demonstrates that legal principles developed to solve specific structural problems within one area of the Penal Code cannot be universally applied to contexts where those problems do not exist. By rejecting the defendant's intricate but ultimately irrelevant structural argument, the Court ensured that the fundamental goal of the law—protecting a person's health from adverse changes—was upheld, providing a clear and pragmatic precedent for future cases.