Defining "Gift" in Capital Gains: The Japanese Supreme Court on Gifts with Assumed Debts

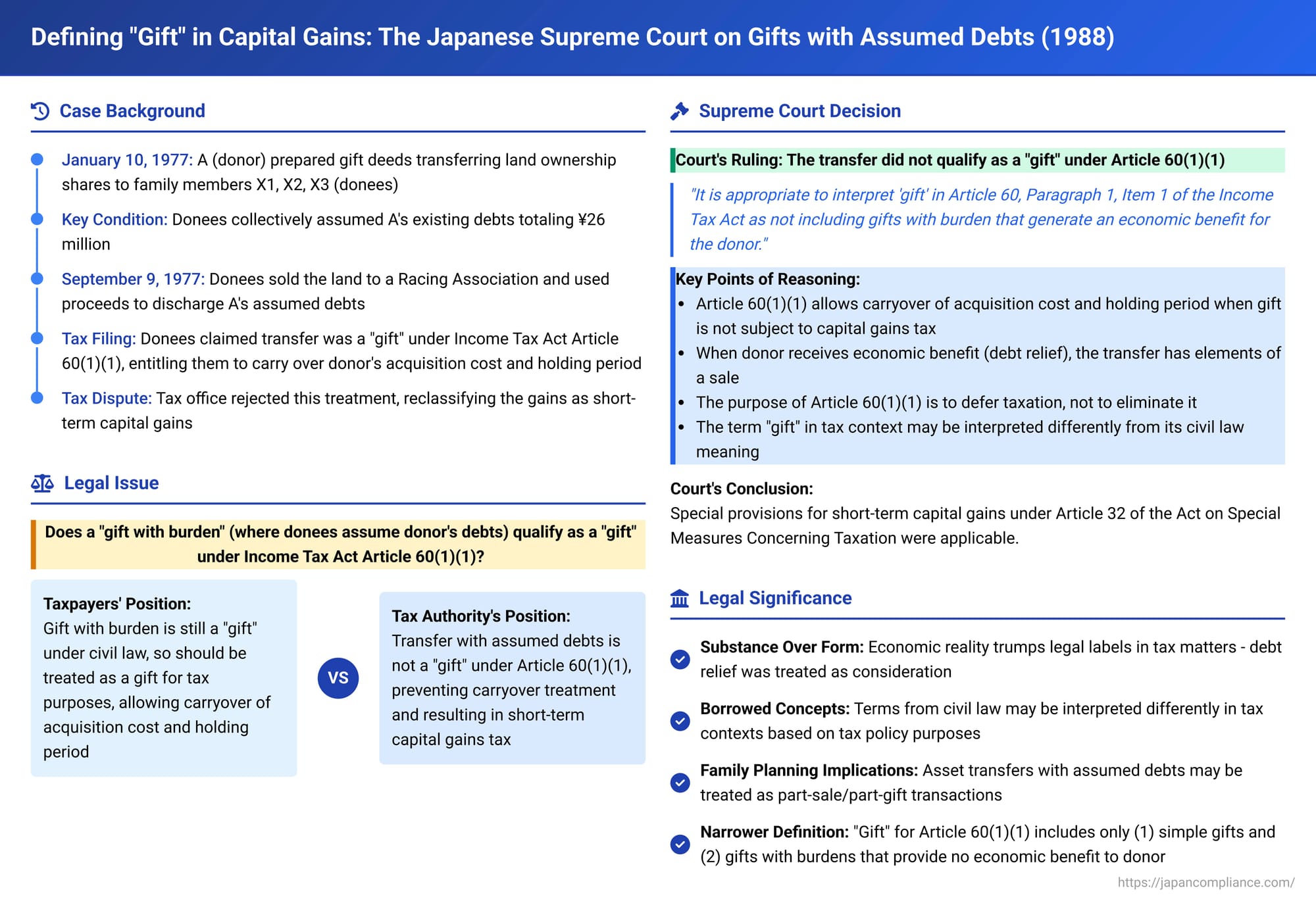

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of July 19, 1988 (Showa 62 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 142: Action for Rescission of Taxable Disposition)

Introduction

On July 19, 1988, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the definition of "gift" (贈与, zōyo) for the purposes of Japanese capital gains tax, specifically in the context of a "gift with burden" (負担付贈与, futantsuki zōyo). This type of transaction involves a donor transferring an asset to a donee, with the donee simultaneously agreeing to assume certain obligations or debts of the donor. The central issue was whether such a transfer qualifies as a "gift" under Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act, which, if applicable, allows the donee to carry over the donor's original acquisition cost and holding period for the asset. This carryover treatment can significantly impact the calculation of capital gains tax upon the donee's subsequent sale of the asset, particularly affecting whether the gain is classified as long-term (often taxed more favorably) or short-term.

The case involved family members where land was transferred with the recipients assuming substantial debts of the donor. The tax authorities challenged the donees' claim that this transaction was a "gift" qualifying for the carryover of basis and holding period.

Facts of the Case

A, the donor (not a party to this specific appeal but central to the transaction), owned two parcels of land, referred to as Parcel 甲 and Parcel 乙 (collectively, "the Land"), situated near the Hamana Lake boat race course. A had inherited the Land on March 31, 1965, from his father, who had originally acquired it prior to December 31, 1952.

In early 1977, discussions between A and the local Boat Race Enterprise Group ("the Racing Association") regarding the sale of the Land to the Association became concrete. On February 28, 1977, the Racing Association's plenary council decided that there was no objection to acquiring the Land.

Concurrently, gift deeds dated January 10, 1977, were prepared. These deeds stipulated the following transfers:

- A 1/2 co-ownership share of Parcel 甲 was gifted by A to X1 (A's wife, an appellant in this case) and A's eldest son.

- A 1/2 co-ownership share of Parcel 乙 was gifted by A to X2 (A's child, an appellant) and another 1/2 co-ownership share of Parcel 乙 to X3 (also A's child, an appellant).

Crucially, these gift deeds contained a special provision: the donees (X1, X2, X3, and A's eldest son) collectively agreed to assume A's existing debts to third parties, which totaled 26 million yen.

At the time of this transfer, the inheritance tax valuation (a proxy for fair market value in some contexts) of the co-ownership share received by X1 was 10,066,337 yen. The shares received by X2 and X3 were each valued at 8,400,125 yen.

Subsequently, A sold his remaining interest in other land to the Racing Association. X1, X2, and X3 also proceeded to sell their newly acquired co-ownership shares in the Land to the Racing Association under a sale and purchase agreement. On September 9, 1977, X1, X2, and X3 received the sale proceeds from the Racing Association for their shares of the Land, and on the same day, they discharged A's debts that they had assumed.

In their income tax returns for the 1977 tax year, X1, X2, and X3 calculated their capital gains from the sale of the Land on the premise that they had acquired their shares by "gift" from A. They therefore contended that Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act applied. This provision allows a donee to inherit the donor's acquisition cost (basis) and holding period. This treatment, in turn, would have allowed them to classify their gains as long-term capital gains, making them eligible for preferential tax treatment under Article 31 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (as it stood before its 1980 amendment).

However, Y, the director of the competent tax office (the appellee), disagreed with this assessment. Y asserted that the land transfer from A to X1, X2, and X3 was not a "gift" for the purposes of Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1. Consequently, the carryover of A's acquisition cost and holding period was not permissible. Instead, Y calculated the gains based on the donees' own acquisition cost (effectively, the amount of debt they assumed) and a short holding period. This resulted in the gains being classified as short-term capital gains, subject to less favorable tax treatment under Article 32 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation. Y issued reassessment dispositions reflecting this increased tax liability and also imposed underpayment penalties. X1, X2, and X3, after unsuccessful administrative appeals, filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of these dispositions.

The Shizuoka District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled against the appellants. It interpreted "gift" in Article 59, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act (which deals with deemed income in certain transfers) as encompassing only (a) simple gifts where the donee bears no burden, and (b) gifts with a burden where the burden provides no economic benefit to the donor. The court reasoned that Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 (the provision at issue here) defers capital gains tax for the donor on the premise that no such tax is imposed on the donor at the time of the gift. It concluded that "gift" in both Article 59 and Article 60 should have the same narrow meaning, thereby excluding gifts with a burden that confer an economic benefit on the donor.

The appellants appealed to the Tokyo High Court, arguing that since "gift" in private law ordinarily includes gifts with burden, it should also be interpreted this way for tax law purposes unless explicitly stated otherwise. The High Court, however, dismissed their appeal. While acknowledging that "gift with burden" is a type of gift under private law and that Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 does not explicitly exclude it, the High Court stated that "even in the interpretation of tax laws, one should not necessarily be bound only by the literal wording of the legal text, but should consider the substantive meaning of the said legal provision and interpret it reasonably in light of that meaning". It concluded that "gift" in Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 does not include gifts with burden that result in an economic benefit to the donor, and that this interpretation does not violate the principle of nulla poena sine lege in taxation (租税法律主義, sozei hōritsu shugi, meaning taxation must be based on law).

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1, X2, and X3, thereby upholding the decisions of the lower courts. The Court's reasoning was concise, largely affirming the High Court's interpretation:

"The land ownership (co-ownership share) transfer agreement, which caused the appellants X1, X2, and X3 to assume the non-party A's total debts of 26 million yen, constitutes a gift with burden agreement". "It is appropriate to interpret 'gift' in Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act as not including gifts with burden that generate an economic benefit for the donor". "Furthermore, the said land ownership (co-ownership share) transfer agreement does not fall under a transfer as stipulated in Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the same Article". "Therefore, Paragraph 1 of the said Article does not apply to the capital gains of the appellants for the 1977 tax year, and ultimately, the special provisions for taxation of short-term capital gains under Article 32 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (prior to the 1980 amendment by Law No. 9) are applicable". The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's findings and judgment, based on the evidence and reasoning presented in the High Court's decision, were correct and could be affirmed.

Commentary Insights

This Supreme Court decision is a key ruling on the interpretation of "gift" within the specific context of Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act, which deals with the carryover of basis and holding period in certain non-taxable or tax-deferred transfers.

The Core Issue: Meaning of "Gift" in Article 60(1)(1)

The central point of contention was the interpretation of the term "gift" in Income Tax Act Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1. If a transaction qualifies as a "gift" under this provision, the donee is allowed to "step into the shoes" of the donor, inheriting the donor's original acquisition cost and holding period for the asset. This is particularly important because it can affect whether a subsequent sale by the donee results in a long-term capital gain (often taxed at lower rates) or a short-term capital gain. The application of special tax rate provisions under the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation also hinges on this classification.

"Gift" as a Borrowed Concept from Civil Law

The commentary accompanying the case notes that "gift" is generally understood in tax law as a "borrowed concept" (借用概念, shakuyō gainen) from the Civil Code. Regarding the interpretation of such borrowed concepts, a prevailing view, as articulated by scholar Hiroshi Kaneko, is that "unless it is clear from the explicit provisions of tax statutes or their legislative intent that they should be interpreted otherwise, it is preferable from the standpoint of legal stability to interpret them in the same sense as in private law".

Based on this general principle, some scholars argued that "gift" in Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act should naturally include "gift with burden," as this is consistent with its meaning in private (civil) law. However, another perspective is that the meaning of borrowed terms in tax law should be interpreted in a way that aligns with the unique objectives and purposes of the tax legislation itself.

The High Court in this case acknowledged that "a gift with burden is a type of gift under private law, and there is no provision in the text of Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act that excludes gifts with burden". Despite this, the High Court, and subsequently the Supreme Court by affirming it, opted for a narrower interpretation for tax purposes. The High Court emphasized that "even in the interpretation of tax laws, one should not necessarily be bound only by the literal wording of the legal text, but should consider the substantive meaning of the said legal provision and interpret it reasonably in light of that meaning," thereby concluding that "gift" in this context "does not include gifts with burden that generate an economic benefit for the donor". This interpretation also found support among some legal scholars.

The commentary further elaborates that while "gift" in a broad sense can encompass gifts with burden, there are distinct differences even within civil law. A "simple gift" (単純贈与, tanjun zōyo) under Article 549 of the Civil Code is contrasted with a "gift with burden" under Article 553, which cross-references rules applicable to bilateral contracts, such as warranty against defects, right to claim simultaneous performance, and allocation of risk. This suggests that "it is not inevitable that 'gift' in its narrow sense (Civil Code Art. 549) must include gift with burden" for tax law purposes if the specific context and purpose of the tax provision warrant a distinction.

The Purpose and Significance of Income Tax Act Article 60(1)(1)

To understand the courts' restrictive interpretation, it's crucial to consider the purpose of Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1. The High Court provided an insightful explanation, which the Supreme Court implicitly endorsed:

- "Capital gains taxation under Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act is intended to tax, as income, the increase in value (appreciation) of an asset that has accrued to its owner, taking the opportunity of the asset being transferred from the owner's control to another to liquidate and tax this gain". Importantly, "the transfer of an asset as referred to in this provision is not limited to onerous transfers (sales, exchanges) but can also include gratuitous transfers such as gifts and other acts of uncompensated rights transfer" (referencing a Supreme Court judgment from May 27, 1975).

- Article 60, Paragraph 1, however, "establishes an exception to this general principle". For cases specified in its subparagraphs (which, when read in conjunction with Article 59, Paragraph 1, clearly exclude gifts to corporations), "capital gains tax is not imposed at the time of the transfer".

- Instead, "when the transferee of the asset later transfers it and becomes subject to capital gains tax, for the purpose of calculating the amount of capital gains, it is deemed that the transferee had continuously owned the asset from the time of the original transferor's acquisition, and acquired it at the transferor's acquisition cost". This mechanism is known as "carryover of acquisition cost," which results in a "deferral of the timing of taxation".

- Crucially, "therefore, for this deferral of taxation timing to be permitted, it must be a case where, even if an asset is transferred, capital gains tax is not imposed at that time".

In essence, Article 60(1)(1) aims to avoid imposing capital gains tax on a donor who makes a purely gratuitous transfer (receiving no actual income), while ensuring that the accrued gain does not escape taxation altogether by transferring the tax liability (based on the original cost and holding period) to the donee upon their eventual sale of the asset.

Considering this purpose, the High Court reasoned that "in a gift with burden, there may be cases where the donor receives an economic benefit, such as an 'amount to be received as revenue' as defined in Article 36, Paragraph 1". "In such cases, if it falls under Article 59, Paragraph 2 (related to transfers at a significantly low price), transfer losses are not recognized, but it may qualify under Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 2 as a transfer not subject to immediate capital gains tax (meaning the gain is not liquidated at that time)". "Otherwise," the High Court continued, "the economic benefit to the donor is subject to capital gains tax according to general principles".

Based on this framework, the prevailing interpretation is that "gift" as used in Income Tax Act Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1, encompasses only (a) simple gifts where the donee undertakes no burden, and (b) those gifts with a burden where the burden assumed by the donee does not result in any economic benefit to the donor. This interpretation is seen as consistent with the general understanding of borrowed legal concepts and the principle of legality in taxation (sozei hōritsu shugi).

Significance and Remaining Issues of the Supreme Court Ruling

This Supreme Court decision therefore clarified that "gift" in the context of Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Income Tax Act is limited to simple gifts and those gifts with burdens that do not provide an economic benefit to the donor.

However, the commentary points out a potential lack of clarity, as the Supreme Court's ruling did not explicitly engage with the theoretical debate surrounding "borrowed concepts" but instead interpreted Article 60(1)(1) based on its "substantive meaning". This has led some scholars to argue for the necessity of an explicit statutory provision stating that "gift" under this article excludes gifts with burden that result in an economic benefit to the donor, to remove any ambiguity.

Related Case Concerning the Donor

It is also noted that a separate lawsuit was filed by A (the donor in this transaction) concerning his own capital gains tax liability arising from this transfer. His claims were dismissed at all levels of the court system, consistent with the outcome of the present case. This implies that the portion of the transfer corresponding to the assumed debt was likely treated as a taxable sale by A.

Broader Implications and Discussion

This 1988 Supreme Court decision has several broader implications for tax law and planning in Japan:

- Substance Over Form: The ruling underscores the importance of economic substance over mere legal form in tax law. Even though a transaction might be labeled a "gift" and involve donative intent, if it includes elements of consideration (like debt assumption benefiting the donor), the tax treatment may deviate from that of a pure gift.

- Family Asset Transfers: The case highlights the complexities involved in structuring intra-family asset transfers. Achieving specific tax outcomes, such as the carryover of basis and holding period to defer or minimize capital gains tax, requires careful planning and adherence to the nuanced interpretations of tax law provisions. A gift with a burden that relieves the donor of significant debt is likely to be treated, at least in part, as a sale by the donor and an acquisition by the donee at a cost equivalent to the debt assumed.

- Interaction of Tax Law Provisions: The decision demonstrates the intricate interplay between different articles of the Income Tax Act, such as Article 59 (which can deem certain transfers at low consideration or no consideration to corporations as taxable events at fair market value for the transferor) and Article 60 (which provides for tax deferral and carryover basis in specific non-recognition transfers between individuals). The underlying policies of these provisions – such as taxing deemed income versus deferring tax – must be considered together.

- "Economic Benefit" as Consideration: The ruling implicitly treats the assumption of the donor's debt by the donee as an "economic benefit" to the donor, which can be equated to sale proceeds for the portion of the asset corresponding to the value of the debt relieved. This aligns with general tax principles where relief from liability can constitute income or proceeds.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary prompt further examination of when it is appropriate not to interpret a borrowed legal concept in the same way as in its original field of law, and whether "consideration" can be found in a "burden" that provides an economic benefit to the donor. These questions point to the ongoing refinement of tax law principles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 19, 1988, judgment provides a critical interpretation of "gift" for the specific purpose of Income Tax Act Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 1. By excluding gifts with burdens that confer an economic benefit upon the donor from the scope of this provision, the Court prioritized the substantive economic reality of the transaction and the legislative intent behind the tax deferral mechanism. This decision means that for a donee to benefit from the carryover of the donor's acquisition cost and holding period, the transfer must essentially be a pure gift or one where any burden assumed by the donee does not translate into a tangible economic gain for the donor. This ruling serves as a key precedent in understanding the tax implications of encumbered donative transfers in Japan.