Defining "Fair Price" in Shareholder Appraisal Rights: A 2011 Japanese Supreme Court Clarification on Valuation

Judgment Date: April 19, 2011

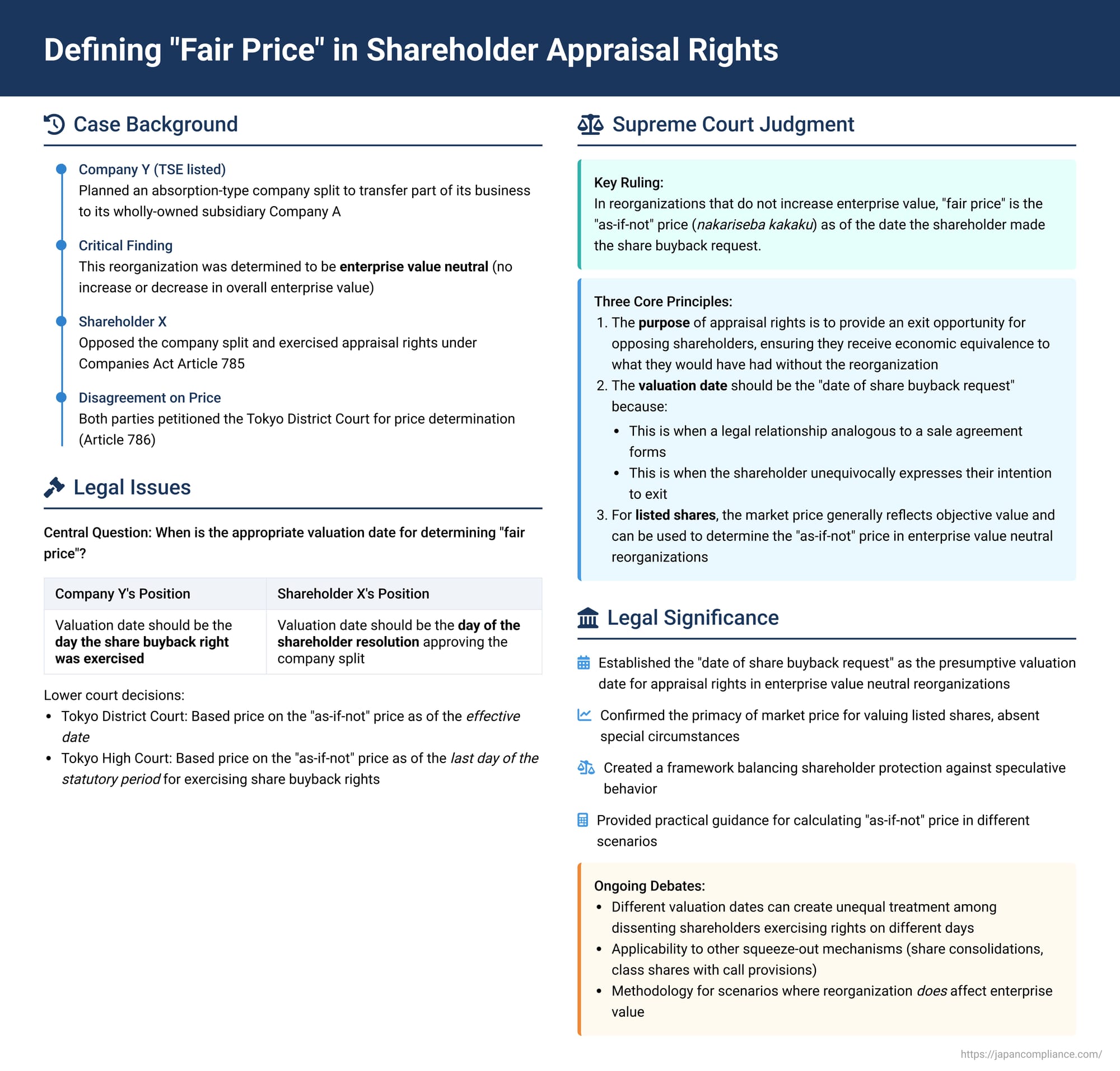

When a Japanese company undergoes a major corporate reorganization, such as a merger, demerger (company split), or share exchange, shareholders who oppose the transaction are often granted a statutory "appraisal right" (株式買取請求権 - kabushiki kaitori seikyūken). This right allows them to demand that the company buy back their shares at a "fair price." However, the Companies Act itself does not explicitly define "fair price" or detail the precise methodology for its calculation, particularly the crucial "valuation date" (算定基準日 - santei kijunbi) on which this price should be based. A 2011 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided significant clarification on these points, especially in scenarios where the reorganization does not generate any synergistic value or increase in the company's enterprise value.

The Corporate Reorganization and the Dissenting Shareholder

The case involved Y Kabushiki Kaisha (Y KK), a company whose shares were listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Y KK planned an absorption-type company split (吸収分割 - kyūshū bunkatsu), a form of demerger where Y KK (the splitting company) would transfer a portion of its business to its wholly-owned subsidiary, A Kabushiki Kaisha (A KK, the successor company). The primary purpose of this reorganization was to enable Y KK to transition into a "certified broadcasting holding company" (認定放送持株会社 - nintei hōsō mochikabu gaisha) under Japan's Broadcasting Act.

A critical finding of fact by the lower courts, and accepted by the Supreme Court, was that this particular absorption-type company split neither increased nor decreased Y KK's overall enterprise value ("enterprise value neutrality" - 企業価値不変 - kigyō kachi fuhen). Consequently, the reorganization itself did not cause any change in the intrinsic value of Y KK's shares.

X Kabushiki Kaisha (X KK), a shareholder of Y KK, opposed this absorption-type company split. As permitted by the Companies Act (Article 785), X KK exercised its appraisal right, demanding that Y KK buy back its shares at a "fair price." When Y KK and X KK could not agree on this price, both parties petitioned the Tokyo District Court to make a determination, as provided for in Article 786 of the Companies Act.

A key point of contention was the appropriate valuation date for determining the fair price. Y KK argued that the valuation date should be the day X KK formally exercised its share buyback right. X KK, on the other hand, contended that the valuation date should be the day of the shareholder resolution approving the absorption-type company split.

The Tokyo District Court, in its initial ruling, determined the buyback price based on what it considered the "as-if-not" price (nakariseba kakaku – the hypothetical price the shares would have had if the reorganization had not occurred) as of the effective date of the company split. However, the actual price it set was a higher figure that Y KK had offered. The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, modified this, basing its calculation of the "fair price" on the nakariseba kakaku as of the last day of the statutory period during which shareholders could exercise their share buyback rights. X KK, still dissatisfied, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Key Principles on "Fair Price" and Valuation Date

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated April 19, 2011, dismissed X KK's appeal, but in doing so, it laid down several important principles regarding the determination of a "fair price" and the appropriate valuation date under the appraisal right statute.

1. The Purpose of Shareholder Appraisal Rights

The Court began by outlining the legislative intent behind granting appraisal rights to dissenting shareholders:

- To provide an opportunity for shareholders who oppose a fundamental corporate change (like a merger or demerger, which is typically approved by a majority shareholder vote) to exit the company.

- To ensure that shareholders who choose to exit are placed in an economically equivalent situation to what they would have been in had the reorganization not occurred. This often involves determining the nakariseba kakaku.

- Furthermore, if the reorganization results in synergy or other increases in enterprise value, to allow these exiting shareholders to also receive an appropriate share of such increased value. This serves to protect the interests of these dissenting shareholders to a certain extent.

2. Determining "Fair Price" When No Enterprise Value Increase Occurs

Building on this understanding of purpose, the Court addressed how to determine "fair price" when the reorganization does not generate any increase in enterprise value:

- In such cases, there is no increased enterprise value to distribute to the dissenting shareholders.

- Therefore, the "fair price" should be determined by calculating the "as-if-not" price (nakariseba kakaku) – that is, the price the shares would have had if the shareholder resolution approving the absorption-type company split (or other similar reorganization) had not been passed.

3. The Valuation Date: The "Date of Share Buyback Request"

This was a central issue. The Supreme Court concluded that the "fair price" should, in principle, be determined based on the circumstances existing on a specific day:

- The date the share buyback request is actually made by the dissenting shareholder is the most rational valuation date.

- The Court provided two main reasons for this choice:

- This is the point in time when a legal relationship analogous to a sale and purchase agreement comes into existence between the shareholder and the company due to the exercise of the appraisal right. The company becomes obligated to buy, and the shareholder (generally) cannot unilaterally withdraw their request (Companies Act Article 785, Paragraph 6).

- This is also the point at which the shareholder has unequivocally expressed their intention to exit the company.

- The Court rejected later valuation dates (such as the last day of the request period or the effective date of the reorganization). It reasoned that using a date after the shareholder has made their buyback request would inappropriately subject the shareholder (who cannot then withdraw their request without company consent) to the risks of share price fluctuations caused by general market factors or other events unrelated to the specific reorganization, occurring after they had already committed to selling.

- The Court also rejected earlier valuation dates, such as the date of the shareholder resolution approving the reorganization. It noted that the statutory period for exercising the buyback right typically starts much later (e.g., 20 days before the reorganization's effective date). If the resolution date were used, the shareholder would bear no risk from general market fluctuations unrelated to the reorganization that occur in the potentially lengthy intervening period between the resolution and their actual buyback request. The Court deemed this also to be inappropriate.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that in cases where a corporate reorganization (like an absorption-type merger, demerger, or share exchange under Article 782, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act) does not result in any increase in synergy or other enterprise value, the "fair price" for a dissenting shareholder's shares is, in principle, the nakariseba kakaku as of the date the shareholder made their share buyback request.

4. Using Market Price in Value-Neutral Reorganizations

The Court then addressed how to determine the nakariseba kakaku when shares are publicly traded and the reorganization itself is value-neutral:

- For publicly listed shares, their market price generally reflects the company's objective value, considering its assets, financial status, profitability, and future prospects, as evaluated by investors. Thus, using the market price as a basis for calculating the nakariseba kakaku on the date of the buyback request is reasonable, unless there are special circumstances suggesting the market price does not reflect objective value.

- Typically, the market price on the date of a buyback request would already incorporate the market's reaction to the announced reorganization. Therefore, directly using this market price as the nakariseba kakaku might not be appropriate if the reorganization itself is expected to affect share value. In such cases, to eliminate the reorganization's influence, courts might refer to pre-announcement market prices (as a "reference share price") or adjust such pre-announcement prices for general market movements that occurred up to the date of the buyback request. The specific methodology is within the court's reasonable discretion.

- However, in a specific situation like the present case, where the absorption-type company split was found to have neither increased nor decreased the company's enterprise value and thus had no impact on its share value, the Court reasoned that the actual market share price itself could be considered not to have been influenced by the reorganization.

- Therefore, in such instances of value neutrality, using the actual market price on the date of the share buyback request (or an average of market prices over a period close to that date) to determine the nakariseba kakaku is within the court's reasonable scope of discretion.

Application to the Facts of the Case

Applying these principles to Y KK and X KK:

- The absorption-type company split involving Y KK and A KK did not generate synergy, nor was it found to have increased Y KK's enterprise value.

- Thus, the "fair price" for X KK's shares was the nakariseba kakaku as of March 31, 2009, the date X KK made its buyback request.

- Since there were no circumstances suggesting Y KK's market share price did not reflect its objective value, and given that this specific reorganization did not alter Y KK's share value, the High Court's decision to use the closing market price of Y KK's shares on the Tokyo Stock Exchange on March 31, 2009 (which was ¥1,294 per share) as the nakariseba kakaku was deemed by the Supreme Court to be a reasonable exercise of judicial discretion and was upheld.

Separate Judicial Opinions

The Supreme Court's decision included a concurring opinion from Justice Mutsuo Tahara and a separate opinion from Justice Kohei Nasu.

- Justice Tahara's Concurring Opinion: Agreed with the majority's adoption of the "date of share buyback request" as the valuation date. He elaborated on the legislative history, noting that the old Commercial Code referred to the "fair price the shares would have had if the resolution had not been passed," which led many to use the resolution date. He argued that the Companies Act, by simply stating "fair price," intended to allow for the inclusion of synergy. He supported the "date of request" because it avoids shareholder speculation (which could occur if the resolution date were used, allowing shareholders to observe market movements before deciding) and because it aligns with the point at which the shareholder commits to selling. He also critiqued other potential dates (resolution date, effective date, end of request period) as having various drawbacks concerning risk allocation and shareholder incentives.

- Justice Nasu's Opinion: While concurring with the ultimate outcome (dismissing the appeal), Justice Nasu expressed disagreement with the majority's establishment of the "date of share buyback request" as the principal or default valuation date. He argued that the determination of the valuation date should fall within the broader discretion of the court hearing the price determination petition, based on the specific facts of each case. He suggested that other dates, such as the "last day of the share buyback request period" (as used by the High Court in this case), could also be deemed reasonable. He questioned the necessity and rigidity of the majority's "date of request" principle, suggesting that the courts should have more flexibility in selecting a valuation point that best achieves a "fair price" in the given circumstances, potentially even considering price movements up to the effective date of the reorganization, with appropriate adjustments.

Broader Implications and Ongoing Discussion

This 2011 Supreme Court decision has significantly shaped the landscape for determining fair value in appraisal right cases in Japan.

- The "Date of Share Buyback Request" as the Benchmark: The ruling establishes the "date of request" as the presumptive valuation date, at least in reorganizations where no new enterprise value is created. This provides a degree of predictability for companies and shareholders.

- Calculating Nakariseba Kakaku:

- The case's unique factual finding – that the reorganization itself had no impact on the company's share value – allowed for a straightforward use of the contemporaneous market price as the nakariseba kakaku.

- In more typical scenarios where a reorganization announcement does affect the market price (either positively due to expected synergy, or negatively due to perceived risks or value destruction), calculating the nakariseba kakaku as of the "date of request" becomes more complex. The Court itself alluded to this, suggesting that in such cases, one might need to use pre-announcement market prices as a starting point and potentially adjust them for general market trends that occurred between the announcement and the date of the buyback request, to isolate and remove the effect of the reorganization itself. Subsequent Supreme Court jurisprudence (e.g., a decision on April 26, 2011, concerning a case of enterprise value destruction) has further explored these methodologies.

- The Role of Market Price: The decision reaffirms the importance of market share prices as a primary reference for valuation of listed companies, provided there are no special circumstances indicating that the market price is not reflective of objective corporate value.

- Ongoing Debates: Despite the Supreme Court's guidance, debates continue among scholars and practitioners regarding the optimal valuation date and methodology. Key considerations include:

- Balancing shareholder protection and preventing speculative behavior: An early valuation date (like the resolution date) might shield shareholders from all subsequent market risks but could encourage them to wait and see how the market moves before deciding whether to exercise their appraisal rights.

- Fairness among different dissenting shareholders: Using the "date of request" means that shareholders who submit their requests on different days (within the allowed 20-day window) might receive different "fair prices" if the market is volatile. Some see this as an acceptable reflection of their individual decision-making, while others argue for a single valuation date (like the end of the request period, as the High Court used) for all dissenting shareholders in a given transaction to ensure equality of treatment. Justice Tahara's opinion, however, supports the individual "date of request" approach.

- Applicability to Different Squeeze-Out Scenarios: The valuation date for other types of minority squeeze-outs or appraisal events (e.g., acquisitions of shares with class-wide call provisions, or cash-outs following share consolidations) continues to be a subject of case law development, with courts considering whether the "date of request" principle from this case should apply or if other dates (like the "acquisition date") are more appropriate depending on the specific statutory mechanism.

Conclusion

The April 19, 2011, Supreme Court decision marked a significant step in clarifying the complex issue of determining a "fair price" under Japanese shareholder appraisal rights. By defining "fair price" in no-synergy reorganizations as the "as-if-not" price (nakariseba kakaku), and establishing the "date of share buyback request" as the principal valuation date for such scenarios, the Court provided important guidance. The ruling emphasized that the ultimate determination involves a careful consideration of the reorganization's impact (or lack thereof) on enterprise value and, for listed companies, a nuanced use of market share prices, all within the court's reasonable discretion to ensure an economically equivalent position for dissenting shareholders choosing to exit.