Defining 'Fair Market Value' for Property Tax: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Official Standards vs. Objective Value

Date of Judgment: June 26, 2003

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Fixed Assets Taxation Review Committee's Dismissal Decision (平成10年(行ヒ)第41号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

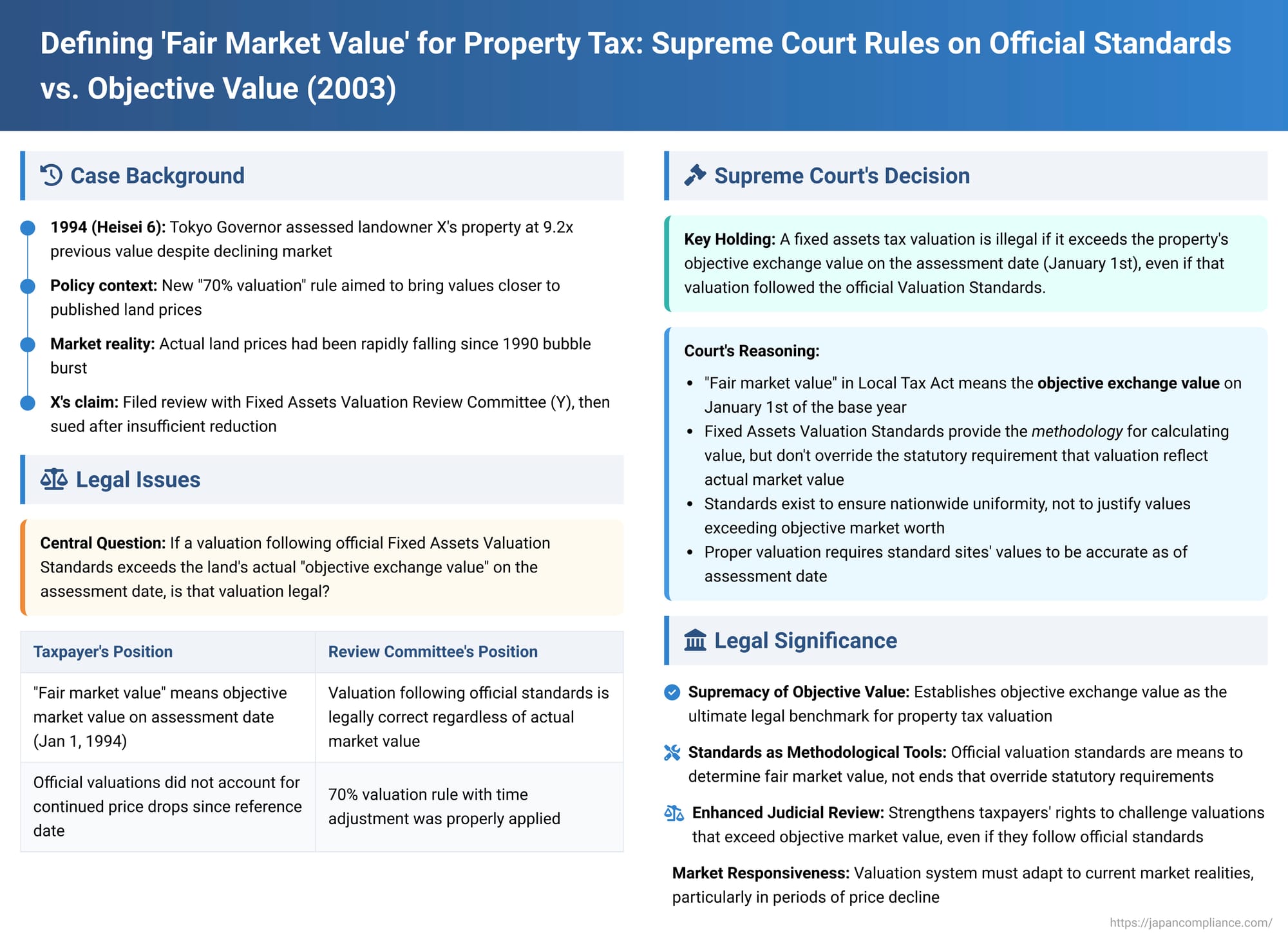

In a landmark judgment on June 26, 2003, the Supreme Court of Japan provided critical clarification on the determination of "fair market value" (適正な時価 - tekisei na jika) for fixed assets tax purposes. The case arose when a landowner challenged a significantly increased property valuation made during a period of declining land prices, arguing that the valuation, despite being based on official government standards, exceeded the land's actual objective market worth. The Supreme Court affirmed that the ultimate benchmark for fixed assets tax valuation is the property's objective exchange value on the assessment date, and that official valuation standards cannot justify a value exceeding this.

The Valuation Shock: Soaring Property Taxes Amidst Falling Prices

The plaintiff, X, was the owner of two parcels of land located in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo ("Land 1" and "Land 2," collectively referred to as "the subject lands"). The dispute concerned the fixed assets tax valuation for the fiscal year 1994 (Heisei 6), which was a "base year" (基準年度 - kijun nendo) for a triennial revaluation of properties across Japan. For this fiscal year, the Tokyo Governor determined the values of X's properties, which were then registered in the land tax ledger by the Chiyoda Ward Tax Office Head. The assessed value for Land 1 was approximately ¥1.255 billion, and for Land 2, approximately ¥12.68 million. This represented a dramatic increase of about 9.2 times their assessed values for the previous fiscal year (FY1993).

X contended that these new valuations were excessively high, exceeded the actual fair market value of the lands, and were therefore illegal. X filed a request for review with Y, the Tokyo Metropolitan Fixed Assets Valuation Review Committee (東京都固定資産評価審査委員会 - Tōkyō-to Kotei Shisan Hyōka Shinsa Iinkai). The Review Committee (Y) subsequently issued a decision slightly reducing the valuations to approximately ¥1.098 billion for Land 1 and approximately ¥11.03 million for Land 2 ("the subject valuation decision"). Still dissatisfied, X initiated a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of Y's decision to the extent that the revised values still exceeded the FY1993 valuations.

The background to this sharp increase in official valuations was a significant policy shift. Historically, fixed assets tax valuations in Japan had often been considerably lower than actual market prices, sometimes estimated at only 10-20% of market value. However, following the asset bubble period of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and amidst calls for strengthening land taxation, a new guideline known as the "70% valuation" rule (7割評価通達 - nana-wari hyōka tsūtatsu) was introduced for the FY1994 revaluation cycle. This administrative circular, issued by the then-Ministry of Home Affairs, instructed local authorities to aim for land valuations that were approximately 70% of the officially published land prices (kōji kakaku - 公示価格, which are official benchmark prices published annually by the Ministry of Land).

Compounding the issue for taxpayers like X, actual land prices in Japan had begun to fall sharply from their peak around 1990. While the 70% valuation policy aimed to bring assessed values closer to (a percentage of) official benchmark prices, these benchmark prices themselves did not always immediately or fully reflect the ongoing rapid decline in the actual transaction market. Furthermore, another administrative notice concerning "time adjustment" (時点修正通知 - jiten shūsei tsūchi) had been issued, instructing consideration of land price trends between the official price survey date for the FY1994 revaluation (July 1, 1992) and January 1, 1993, when applying the 70% guideline. However, X argued that even these adjusted figures did not accurately capture the further decline in market values up to the actual assessment date for FY1994, which was January 1, 1994.

The lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) partially sided with X. They found that the official valuation, even after the Review Committee's revision, still exceeded the objective market value of the lands as of January 1, 1994. The courts recalculated the values based on what they determined to be the actual objective exchange values of the "standard sites" (標準宅地 - hyōjun takuchi) used as benchmarks for valuing X's properties, taking into account the continued price decline up to the assessment date. The Review Committee (Y) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Battle: "Fair Market Value" vs. Fixed Assets Valuation Standards

The core legal dispute revolved around the interpretation of "fair market value" (tekisei na jika) under the Local Tax Act and the legal status of the Fixed Assets Valuation Standards (固定資産評価基準 - Kotei Shisan Hyōka Kijun).

- The Local Tax Act (Article 349, paragraph 1) stipulates that the tax base for fixed assets tax is the "price" (kakaku) of the fixed asset as registered in the tax ledger on the assessment date (January 1st) of the base year. Article 341, item 5 of the Act defines this "price" as the "fair market value".

- Article 388, paragraph 1 of the Local Tax Act mandates that the Minister of Home Affairs (now the Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications) shall establish the standards for the valuation of fixed assets and the methods and procedures for their implementation, and issue these as a public notice (告示 - kokuji). Municipal heads must then determine property values in accordance with these Fixed Assets Valuation Standards (Article 403, paragraph 1).

The critical question was: If a valuation determined by strictly following the official Fixed Assets Valuation Standards (including administrative guidelines like the 70% rule and any prescribed time adjustments) nevertheless results in a value that is higher than the land's actual "objective exchange value" on the statutory assessment date, is that valuation legal? In essence, what is the hierarchy between the statutory mandate to assess at "fair market value" and the administrative requirement to follow the Valuation Standards?

The Supreme Court's Decision: Objective Exchange Value is Paramount

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by the Tokyo Metropolitan Fixed Assets Valuation Review Committee (Y), thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of the taxpayer (X). The Supreme Court ruled that a fixed assets tax valuation is illegal if it exceeds the property's objective exchange value on the assessment date, even if that valuation was derived by adhering to the official Fixed Assets Valuation Standards.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Meaning of "Fair Market Value": The term "price" in Article 349, paragraph 1 of the Local Tax Act, which constitutes the tax base, explicitly means the "fair market value" as of the assessment date of the relevant base year. There is no legal basis for using a value from any other point in time for registration in the land tax ledger. The Court characterized fixed assets tax on land as a type of property tax, levied on the asset value of the land and recognizing the taxable capacity inherent in its ownership, irrespective of the individual land's current profitability. Therefore, this "fair market value" must be understood as "the transaction price that would be formed under normal conditions, that is, the objective exchange value (客観的な交換価値 - kyakkanteki na kōkan kachi)" of the land. Consequently, if the price registered in the land tax ledger exceeds this objective exchange value as of the assessment date, the determination of that price is illegal.

- Legal Status of the Fixed Assets Valuation Standards: The Local Tax Act indeed delegates to the Minister the authority to establish the Fixed Assets Valuation Standards (Art. 388(1)) and requires municipal heads to use these Standards in determining property values (Art. 403(1)). The purpose of this mandate is to ensure nationwide uniformity and consistency in valuation, thereby achieving equity in assessments across all municipalities and eliminating disparities that might arise from the subjective judgments of individual assessors. However, the Supreme Court clarified the limits of this delegation. While the Act delegates the authority to establish "technical and detailed standards for calculating" fair market value, it does not delegate the authority to prescribe standards that would result in determining a price exceeding the objective exchange value as of the assessment date. The Valuation Standards are a tool to ascertain the objective exchange value, not to supplant it.

- Application to the Valuation Method: The "urban land valuation method" (市街地宅地評価法 - shigaichi takuchi hyōka hō) within the Valuation Standards prescribes that individual land parcels should be valued based on the fair market value of designated "standard sites". For the value thus calculated for an individual parcel to be presumed not to exceed its objective exchange value, it is essential that the fair market value determined for the benchmark "standard sites" does not itself exceed their objective exchange value as of the actual assessment date (January 1st).

- Illegality in X's Case: In X's case, the lower courts had found that the values determined for the relevant standard sites (Standard Site 甲 and Standard Site 乙), after applying the 70% Valuation Guideline and the Time Adjustment Notice (which used a reference point prior to the January 1, 1994 assessment date), did in fact exceed the actual objective exchange values of those standard sites as of January 1, 1994. When the lower courts recalculated the values of X's lands by applying the Valuation Standards' methodology but using the correct, actual objective exchange values of the standard sites as of January 1, 1994, they arrived at lower figures for X's properties. The Supreme Court affirmed that the Review Committee's (Y's) valuation decision, to the extent it exceeded these correctly recalculated figures, was illegal because it was ultimately based on standard site values that were themselves inflated above their objective exchange value on the crucial assessment date.

Key Principles and Implications

This Supreme Court judgment is a leading case in Japanese fixed assets tax law and has several important implications:

- Supremacy of Objective Exchange Value: The ruling firmly establishes that the ultimate legal benchmark for the valuation of property for fixed assets tax is its "objective exchange value" as of the assessment date (January 1st of the base year). Any valuation, even one meticulously following official administrative standards, that exceeds this objective value is illegal.

- Fixed Assets Valuation Standards as Methodological Tools, Not Determinants of Value: The decision clarifies that the Fixed Assets Valuation Standards are legally binding as the methodology for achieving fair and uniform valuations. However, they are tools to arrive at the statutorily mandated "fair market value" and do not have the authority to define or legitimize a value that is demonstrably higher than the actual objective exchange value of the property on the assessment date.

- Impact on the "70% Valuation" Policy: The judgment was particularly significant in the context of the "70% valuation" policy. It implicitly confirmed that this policy (or any other adjustment mechanism within the Valuation Standards) cannot be applied in such a way as to justify assessing a property at a value greater than what it would objectively fetch in a normal market transaction on January 1st.

- Judicial Review of Official Valuations: The decision reinforces the power of judicial review over administrative valuations. Taxpayers have the right to challenge fixed assets tax valuations in court if they can provide evidence that the assessed value exceeds the property's true objective exchange value, even if the assessing authorities assert that they have correctly applied the official Valuation Standards. This provides an essential check on potentially arbitrary or outdated administrative valuation practices.

- Context of Falling Land Prices: The case arose during a period of significant land price decline following Japan's asset bubble. The rigid application of valuation methodologies based on earlier, higher price levels (even with some adjustments) without full regard to the actual market conditions on the assessment date led to the kind of overvaluation challenged in this case. This ruling underscored the need for the valuation system to be responsive to actual market dynamics up to the assessment date.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2003 decision serves as a critical affirmation of taxpayer rights and provides an essential check on the application of administrative standards in fixed assets tax valuation. It ensures that while national standards are vital for achieving uniformity and fairness in property assessment across Japan, these standards must ultimately operate within the statutory mandate that valuations reflect the property's genuine "objective exchange value" as of the legally prescribed assessment date. This prevents a situation where taxpayers could be subjected to taxation based on inflated or outdated property values that do not correspond to economic reality. The ruling emphasizes that the law requires valuation at fair market value, and administrative standards are the means to that end, not an end in themselves that can override this fundamental legal requirement.