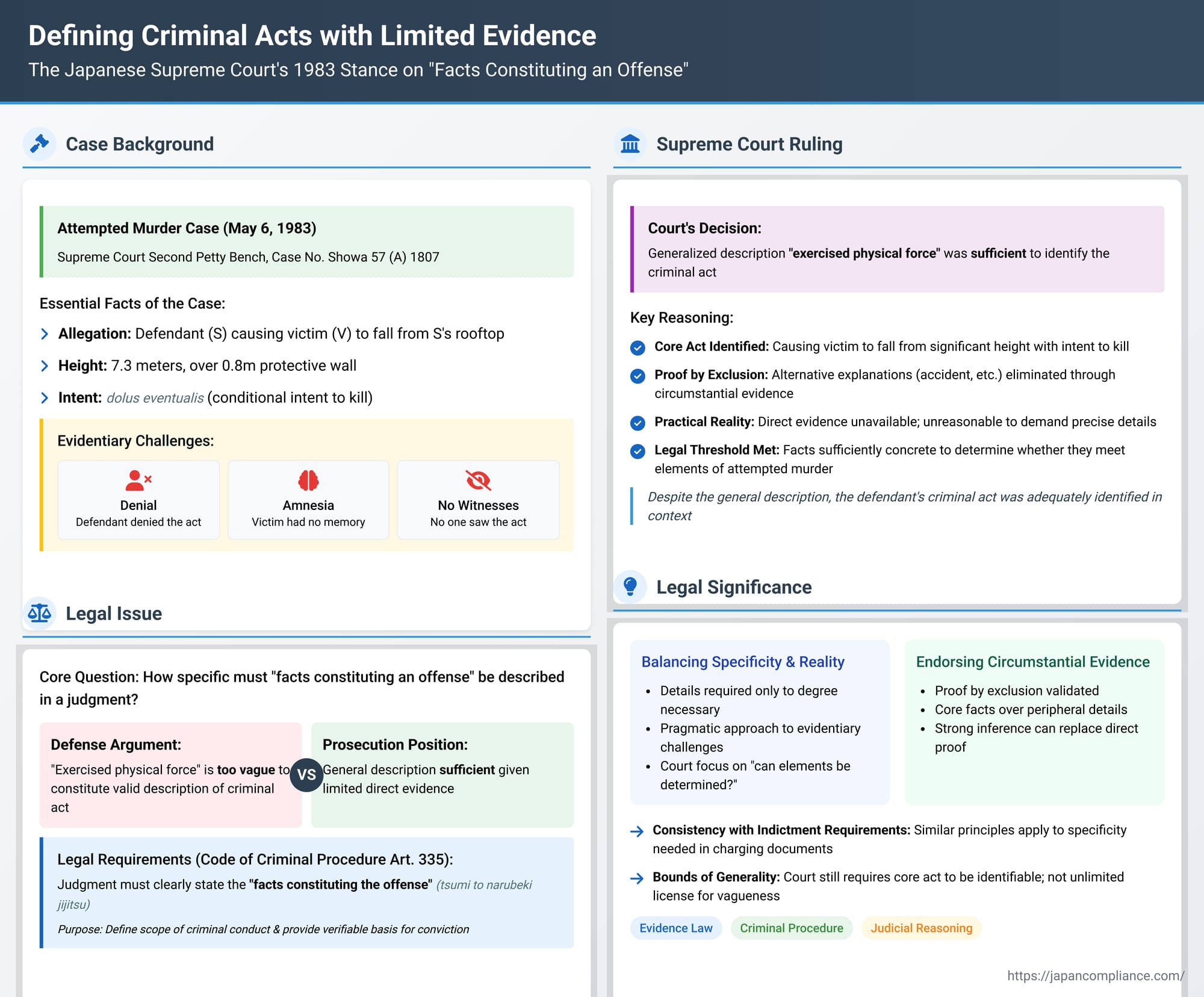

Defining Criminal Acts with Limited Evidence: The Japanese Supreme Court's 1983 Stance on "Facts Constituting an Offense"

On May 6, 1983 (Showa 58), the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant decision in an attempted murder case (Case No. Showa 57 (A) 1807). This case addressed a critical question in criminal procedure: how specifically must the "facts constituting an offense" (tsumi to narubeki jijitsu), particularly the means and methods of the alleged crime, be detailed in a judgment, especially when direct evidence is scarce? The ruling offers valuable insight into the balance between the requirement for specificity in judicial findings and the practical challenges of proving every detail of a criminal act.

Background of the Attempted Murder Case

The defendant, S, was prosecuted for the attempted murder of an individual identified as V. The prosecution's central allegation was that S, acting with conditional intent (dolus eventualis) to kill, caused V to fall from the rooftop of S’s residence. This fall was from a height of approximately 7.3 meters, over a protective wall railing about 0.8 meters high, onto the concrete-paved road on the north side of S's property, resulting in V crashing onto the road surface.

The case presented considerable evidentiary challenges. S, the defendant, denied committing the act. V, the victim, suffered memory loss concerning the incident and could not provide testimony about how the fall occurred. Furthermore, there were no eyewitnesses to the event itself. Consequently, the precise means and methods employed by S to cause V to fall from the rooftop remained unclear. Despite these challenges, S was convicted of attempted murder in the first instance, a decision later upheld by the appellate court, leading to the appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Challenge: Specificity in Describing the Criminal Act

The defense counsel, T, argued before the Supreme Court that the first-instance judgment was flawed. The core of this argument was that the judgment's description of S's actions—specifically, the means and method by which V was caused to fall—was overly general and lacked the necessary specificity. The judgment stated that S had "exercised physical force" (yūkeiryoku o kōshi shite) upon V's body to cause the fall. The defense contended that this phrase alone, without further concrete details of how this force was applied, was insufficient to properly describe the criminal act. This alleged lack of specificity, T argued, constituted a defect in the reasoning of the judgment and was a violation of legal precedent concerning the clear statement of facts constituting an offense.

This challenge touched upon a fundamental principle of Japanese criminal procedure, enshrined in Article 335, Paragraph 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. This article mandates that a judgment rendering a guilty verdict must clearly state the "facts constituting the offense." Legal precedent has established that these "facts" refer to "concrete facts falling under the constituent elements of the crime." The purpose of this requirement is twofold:

- To clearly define the scope of the criminal conduct for which the defendant is being convicted, distinguishing it from any other acts and thereby preventing confusion in legal relations.

- To provide a solid and verifiable foundation for the court's conviction, demonstrating that its finding of guilt is based on established facts that meet the legal definition of the crime.

Therefore, while every minute detail may not always be necessary, the facts must be elucidated "concretely and clearly to a degree sufficient to determine whether they fall under the constituent elements" of the charged offense. The defense's argument, in essence, was that "exercising physical force" did not meet this standard of concrete clarity.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court began by acknowledging the defense's point: the first-instance judgment did indeed describe the means and method of S's alleged action in general terms, without specifying the precise nature of the physical force used.

However, the Court ultimately rejected the defense's argument that this generality rendered the judgment defective. The Supreme Court held that, even with the description of the means and method being limited to "exercised physical force," the defendant S's criminal act was, in this specific context, adequately identified. The Court reasoned that the first-instance judgment’s statement of the facts constituting the offense did clarify the concrete facts corresponding to the constituent elements of attempted murder to a degree sufficient for a court to determine whether S's actions indeed met those legal elements.

The Supreme Court's rationale can be understood through several key considerations, further illuminated by legal commentary on this case:

- Identification of the Core Criminal Act: Despite the generality in describing the how, the judgment clearly identified what S was accused of doing: intentionally causing V to fall from a significant height from the rooftop, an act inherently dangerous to human life, coupled with the finding of conditional intent to kill. The core elements of attempted murder—an act capable of causing death and the requisite intent—were thus addressed by the described facts.

- Proof by Exclusion and Circumstantial Evidence: The PDF commentary on this case highlights a crucial aspect of the trial that likely informed the Supreme Court's decision. Given that S denied the act, V had amnesia, and no eyewitnesses were available, direct evidence of the precise method of the fall was absent. In such situations, the prosecution often relies on circumstantial evidence and a process of elimination to establish guilt.

In this specific case, while the exact method of the fall was unknown, other critical pieces of evidence were successfully proven. These included:Crucially, the prosecution was also able to exclude other possibilities, such as V accidentally falling. By demonstrating that alternative explanations for V's fall were not plausible, the court could, through a process of elimination, arrive at a firm conviction that S was responsible for the act, even if the precise mechanics of how S accomplished this remained somewhat obscure.- The circumstances leading up to the incident.

- The nature, location, and severity of the victim V's injuries, which would have been consistent with a fall from that height.

- The physical conditions and situation at the crime scene (S's rooftop and the ground below).

- Sufficiency for Legal Determination: The Supreme Court found that the level of detail provided was sufficient for the legal determination required. The phrase "exercised physical force," in the context of causing someone to fall 7.3 meters from a rooftop, clearly pointed to an action that, if performed with the requisite intent, would constitute attempted murder. The lack of further specification did not prevent the court from applying the law to the established facts.

Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court concluded that the original judgment (and by implication, the appellate judgment upholding it) was appropriate in its finding of facts. The defense's argument that the generality of the description of means and methods was a fatal flaw was dismissed as lacking a valid premise. Other arguments raised by the defense were summarily dismissed as attempts to re-argue factual errors or allege simple (non-constitutional or non-fundamental) violations of law, none of which constituted permissible grounds for a final appeal under Article 405 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision by the justices of the Second Petty Bench, therefore dismissed S's appeal. It also ordered that 50 days of S's pre-sentence detention be credited towards the final sentence.

Broader Implications of the Ruling

This 1983 Supreme Court decision carries important implications for understanding how Japanese courts approach the requirement of specificity in criminal judgments, particularly in cases where direct evidence of every detail of the offense is lacking.

- Flexibility in Factual Findings: The ruling underscores that while the "facts constituting the offense" must be clearly stated, the level of detail required for describing the means and methods can be subject to the practical realities of evidence collection. When direct evidence is sparse (e.g., due to denial by the accused, memory loss of the victim, or lack of eyewitnesses), courts may rely on a more generalized description of the act, provided that the core criminal conduct is identifiable and the essential elements of the crime are covered by the proven facts.

- The Role of "Proof by Exclusion": The case implicitly supports the validity of "proof by exclusion" or elimination. When circumstantial evidence is strong and alternative, innocent explanations for the event can be convincingly ruled out, a court can form the necessary firm conviction (kakushin) of guilt, even if some aspects of the actus reus are not detailed with precision. The focus shifts from knowing every detail of how the crime was committed to being certain that the defendant committed it.

- Consistency with Specificity in Indictments: Legal commentary suggests that the principles applied in this judgment regarding the particularization of facts in a final judgment also resonate with the requirements for specificity in the initial indictment (the prosecutor's charge sheet, or soin) under Article 256, Paragraph 3 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Prosecutors, too, may sometimes only possess a generalized conviction of guilt at the time of indictment, and the level of detail in the charges must be sufficient to notify the defendant of the accusation while reflecting the available evidence. This decision supports the idea that the legal system allows for a degree of generality if the core accusation is clear.

- Limits of Generality: It is important to note that this decision does not grant an unlimited license for vague factual findings. The Court emphasized that the defendant's criminal act was "specifically identified" and the facts were clarified to a degree "sufficient to determine whether they meet the constituent elements." The generality was permissible because, despite it, the core requirements of criminal liability could still be assessed and established to the court's firm conviction. If the description were so vague as to obscure the nature of the criminal act or prevent a determination of whether legal elements were met, the outcome would likely be different.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in this 1983 attempted murder case provides a nuanced understanding of the requirement to specify "facts constituting an offense" in Japanese criminal judgments. It affirms that while clarity and concreteness are paramount, the courts can, in circumstances where direct evidence is limited, accept a more general description of the means and methods of an offense. This is permissible provided that the overall criminal act is clearly identified, the essential legal elements of the crime are met by the facts as stated, and the court, often through a process of evaluating strong circumstantial evidence and excluding other possibilities, has formed a firm conviction of the defendant's guilt. The ruling balances the ideals of precise judicial findings with the practical necessities of adjudicating cases where evidentiary certainty on every factual detail is unattainable.