Defining Corporate Boundaries: Japan's Supreme Court on Company Purpose and Transaction Validity

The question of a company's legal capacity—what it can and cannot legally do—is fundamental to corporate law. Traditionally, this capacity has often been linked to the "purpose" for which the company was established, as stated in its articles of incorporation. Acts deemed outside this purpose could be considered ultra vires (beyond its powers) and potentially void. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 15, 1952, provided crucial clarification on how to interpret a company's scope of purpose, particularly concerning the validity of its transactions with third parties.

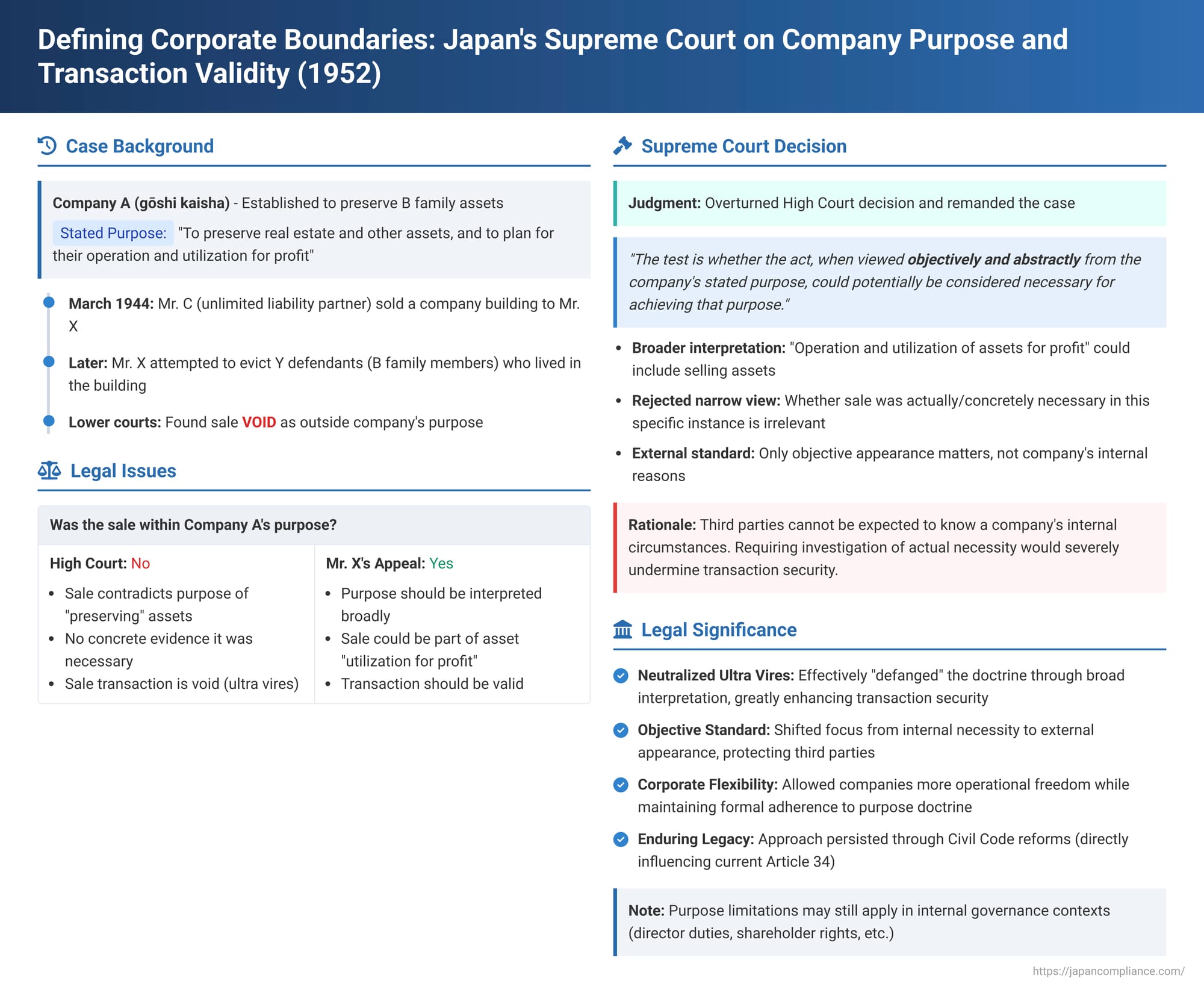

The Factual Background: A Family Company and a Property Sale

The case involved a gōshi kaisha (a form of limited partnership company under Japanese law), referred to as Company A. Company A was established with the objective of preserving the assets of a family, the B family. Its articles of incorporation explicitly stated its purpose as "to preserve real estate and other assets, and to plan for their operation and utilization for profit."

Mr. C was an unlimited liability partner of Company A. In March 1944, acting on behalf of Company A, Mr. C sold a building owned by the company to Mr. X (the plaintiff). However, several members of the B family, the Y defendants, had been residing in this building since before the sale. Following his purchase, Mr. X initiated legal proceedings to evict the Y defendants from the property.

The Lower Courts' Stance: A Strict Interpretation of Purpose

The initial court dismissed Mr. X's claim. On appeal, the Hiroshima High Court upheld this decision. The High Court reasoned that the sale of the building, which was an asset of Company A, did not fall within the company's stated purpose of preserving assets and planning for their operation and utilization for profit. Furthermore, the High Court found no evidence to suggest that, at the time of the sale, it was necessary for Company A to sell the building in order to fulfill its stated objectives. Consequently, the High Court concluded that Company A lacked the authority to sell the building, rendering the sale transaction to Mr. X void. Mr. X appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification: An Objective Approach

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. Its judgment provided a nuanced interpretation of a company's purpose and the validity of its actions.

1. Interpreting the Stated Purpose:

The Court began by examining Company A's stated purpose: "to preserve real estate and other assets, and to plan for their operation and utilization for profit." It found that the High Court was too quick to conclude that selling the building was outside this purpose. The Supreme Court reasoned that "to plan for the operation and utilization of assets for profit" could, at times, involve selling existing assets. For instance, one might sell existing securities to reinvest in others as a method of profitable operation, and the same logic could apply to real estate.

2. Acts Necessary for Fulfilling the Purpose:

Beyond acts that directly fall within the literal wording of the stated purpose, the Court affirmed a broader principle: acts that are necessary for achieving a company's stated purpose are also considered to be within the scope of that purpose, even if not explicitly listed in the articles of incorporation. This principle had been developing in earlier Great Court of Cassation (the predecessor to the Supreme Court) jurisprudence.

3. The "Objective and Abstract Necessity" Test:

This was the most critical part of the Supreme Court's reasoning. The Court established a specific standard for determining whether an act is "necessary" for the fulfillment of a company's purpose:

- The determination should not be based on whether the act in question was actually and concretely necessary for the company in that particular instance, given its internal circumstances at the time.

- Instead, the test is whether the act, when viewed objectively and abstractly from the description of the company's purpose in its articles of incorporation, could potentially be considered necessary for achieving that purpose.

4. Rationale for the Objective Standard: Security of Transactions:

The Supreme Court emphasized the importance of protecting the security of commercial transactions. It reasoned that whether a particular act is genuinely and concretely necessary for a company's purpose from an internal perspective is a matter of the company's internal affairs. Third parties dealing with the company cannot reasonably be expected to know or adequately investigate such internal circumstances. If third parties had to verify the actual, internal necessity of every transaction before they could safely deal with a company, it would severely hamper business dealings and undermine transactional safety.

5. Application to the Case:

Applying this objective and abstract test, the Supreme Court found that the sale of the building by Company A, when viewed in this light, could indeed be considered an act potentially necessary for the preservation, operation, and profitable utilization of the company's assets, as stated in its articles of incorporation. Therefore, the High Court had erred in summarily concluding that the sale was outside Company A's purpose and that Company A consequently lacked the power to sell the building.

(The Supreme Court also noted that the High Court's additional point about the lack of consent from other partners, while potentially relevant to restrictions on Mr. C's representative authority, did not in itself mean the company lacked the capacity or power to sell the building if the act was within its purpose. )

The Doctrine of Ultra Vires in Japan: Context and Evolution

This Supreme Court decision is best understood in the context of the ultra vires doctrine—the legal principle that a corporation cannot engage in acts beyond the scope of powers and purposes granted by its articles of incorporation or founding statutes.

- Origins and Rationale: This doctrine, originating in English law, was incorporated into Japanese law via the Civil Code. When applied to companies, a primary rationale was the protection of shareholders and members who invested their capital with the expectation that company funds would be used only for the specific business purposes outlined in the articles of incorporation.

- Problems with Strict Application: A strict application of the ultra vires doctrine meant that any act deemed outside a company's purpose was absolutely void, irrespective of whether the third party dealing with the company acted in good or bad faith. For commercial companies engaged in a wide array of activities, this rigidity posed significant problems: it could unduly restrict a company's operational flexibility and, more critically, jeopardize the security of transactions by allowing companies to evade contractual obligations by claiming their own actions were ultra vires. Recognizing these issues, both English and American company law substantially moved away from or abolished the strict ultra vires doctrine for companies.

- Japanese Civil Code and Scholarly Debate:

- The pre-2006 Japanese Civil Code (Article 43) stated that a juridical person "has rights and assumes duties within the scope of its purpose as prescribed by laws and regulations and by its articles of incorporation or act of endowment." While this provision was primarily aimed at non-profit corporations, a significant debate arose in commercial law scholarship as to whether it applied by analogy to companies. Initially, the majority view, aligning with earlier case law, affirmed such an analogous application. However, by the period leading up to the 2006 Civil Code reforms, the dominant scholarly opinion had shifted to deny the analogous application to companies. The main arguments against application were the severe harm to transaction security (as third parties would need to verify the purpose for every transaction, and even then, judging if a specific transaction fell within that purpose could be difficult) and the inappropriateness of prioritizing shareholder interests (in limiting purpose) at the expense of innocent third parties.

- Despite this scholarly trend and criticism from company law experts, the 2006 reforms to Japan's legal framework for juridical persons resulted in the enactment of Article 34 of the current Civil Code. This article contains language similar to the old Article 43 and is positioned as a general rule applicable to all juridical persons. Thus, under the current legal structure, unless specific provisions in the Companies Act dictate otherwise (which they generally do not on this specific point of capacity), Civil Code Article 34 is considered to apply directly to companies.

- Evolution of Japanese Case Law: Expanding "Purpose":

The Japanese courts, while formally acknowledging the principle that a company's legal capacity is limited by its stated purpose, progressively broadened the interpretation of what falls "within the scope of purpose" to ensure the security of transactions.- In the Meiji era (late 19th to early 20th century), the Great Court of Cassation adopted a very strict stance: any matter not explicitly stated as a purpose in the articles of incorporation was considered outside the company's legal capacity.

- From the Taisho era (1912-1926) onwards, the interpretation became more flexible. The courts began to hold that:

- The scope of the stated purpose includes matters that can be "inferred or deduced" from the literal text of the articles, recognizing that articles of incorporation aim for conciseness.

- Acts necessary to carry out such an interpreted purpose are also considered within the scope, even if not explicitly mentioned. The 1952 Supreme Court judgment discussed here explicitly affirmed this second criterion.

- Furthermore, regarding what constitutes an act "necessary for the fulfillment of the purpose," Showa-era (1926-1989) Great Court of Cassation decisions had already moved towards an external, objective standard: if an act, judged by its external appearance, could be considered necessary for carrying out the company's stated business, it was deemed within the company's purpose. The 1952 Supreme Court decision emphatically adopted this objective standard, stressing the need to protect transaction security.

The 1952 judgment is thus seen as a crucial step where the Supreme Court clearly endorsed and solidified these evolving interpretative standards. This approach has been consistently followed in subsequent case law. The practical effect of this broad, objective interpretation is that almost any act undertaken by a commercial company can now be considered within its purpose. This has led to the assessment that, for companies, the ultra vires doctrine has been effectively "defanged" or rendered largely non-functional through judicial interpretation, a situation unlikely to change despite the direct applicability of Civil Code Article 34.

Implications of the Objective Standard

The adoption of the "objective and abstract necessity" test by the Supreme Court had significant implications:

- Enhanced Security for Third Parties: It greatly increased the security for third parties dealing with companies. They no longer needed to delve into a company's internal rationale or the actual, subjective necessity of a transaction. If a transaction appeared objectively related to the company's stated business purposes, it was likely to be considered valid.

- Focus on External Appearance: The test shifted the focus from a company's internal decision-making processes and its subjective state of mind regarding a transaction's necessity to the external appearance of the act and its potential connection to the broadly interpreted purposes stated in the articles of incorporation.

Distinction from Internal Governance and Other Contexts

It is important to note that this broad interpretation of a company's purpose, designed to protect external transactions, does not necessarily apply in the same way when issues of internal corporate governance arise. Deviations from the stated purpose can still be relevant in contexts such as:

- Directors' duty of loyalty.

- Shareholders' rights to seek injunctions against directors' actions.

- Shareholders' requests to convene board meetings.

- Auditors' reports to the board.

- Lawsuits for the dismissal of officers.

- Court orders for company dissolution.

- Criminal liability for endangering company assets.

In these internal or regulatory contexts, the interpretation of the "scope of purpose" should not be as extremely broad as it is for validating external transactions. Instead, it should be interpreted reasonably in line with the original intent of the "purpose," taking into account the specific objectives of the relevant legal provision.

Moreover, even if an act is deemed within the company's purpose, if it constitutes an abuse of representative authority by a director (e.g., the director acts for personal gain rather than for the company), the transaction might still be invalidated with respect to a third party who knew or should have known of the director's improper intent, based on general principles of agency law.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 15, 1952, decision represents a critical juncture in Japanese company law. By establishing the "objective and abstract necessity" test for determining whether an act falls within a company's stated purpose, the Court effectively prioritized the security of commercial transactions and the protection of third parties. While formally upholding the principle that a company's legal capacity is defined by its purpose, the Court's expansive interpretative approach significantly curtailed the practical impact of the ultra vires doctrine on the validity of a company's external dealings. This judgment, building on earlier case law trends, has had a lasting legacy, ensuring that companies can operate with greater flexibility in the marketplace while third parties can engage with them with a higher degree of confidence.