Defining "Continuing Act" in Unfair Labor Practices: The Beniya Shoji Case (Supreme Court of Japan, June 4, 1991)

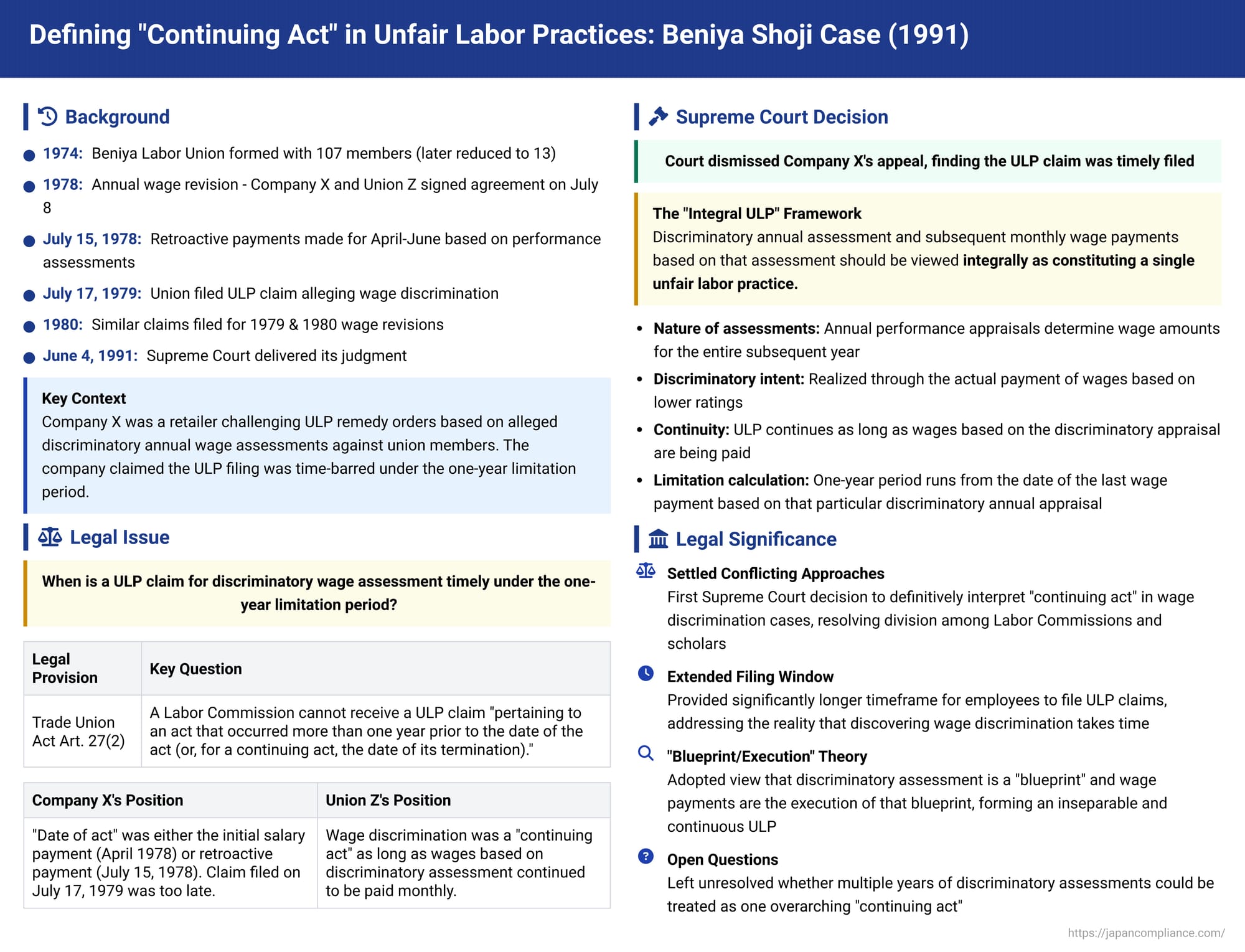

On June 4, 1991, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered an important judgment in the Beniya Shoji case. This ruling provided crucial clarification on the interpretation of "continuing act" under Article 27, Paragraph 2 of the Trade Union Act (TUA), which sets a one-year limitation period for filing unfair labor practice (ULP) claims. The case specifically addressed how this limitation applies to situations involving alleged discriminatory annual wage assessments and subsequent monthly wage payments.

Case Reference: 1989 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 36 (Petition for Rescission of Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order)

Appellant (Original Plaintiff): Company X (Beniya Shoji Co., Ltd.)

Appellee (Original Defendant): Commission Y (Aomori Prefectural Labor Commission)

Appellee-Intervenor: Union Z (Beniya Labor Union)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal concerning the 1978 wage revision ULP claim (First Case) was dismissed, upholding the High Court's finding that the claim was timely. The appeal concerning the 1979 and 1980 wage revisions (Second Case) was dismissed for procedural reasons (failure to submit a statement of grounds for appeal).

Factual Background: Allegations of Wage Discrimination and the Limitation Period

Company X was a retailer operating large stores. Union Z was an enterprise union representing employees of Company X. At the time of the dispute, Union Z was a minority union with 13 members, down from 107 at its formation in December 1974, out of a total workforce of about 170.

The core of the dispute revolved around annual wage revisions and the timeliness of ULP claims:

- The 1978 Wage Revision (First Case):

- Following several rounds of collective bargaining concerning the fiscal year 1978 wage revision, Company X and Union Z signed an agreement on July 8, 1978.

- Based on this agreement and the company's annual performance appraisals (考課査定 - kōka satei), wages for union members were determined. On July 15, 1978, retroactive differential payments for April to June 1978 were made.

- Union Z, believing its members were subjected to discriminatory wage treatment in this revision, filed a ULP claim with Commission Y on July 17, 1979.

- The 1979 and 1980 Wage Revisions (Second Case): Similar wage revisions and subsequent ULP claims by Union Z followed for fiscal years 1979 (claim filed July 22, 1980) and 1980 (claim filed October 2, 1980).

- Company X's Defense – Statute of Limitations: For the First Case (1978 wage revision), Company X argued that the ULP claim was time-barred. It contended that the "date of the act" for the alleged ULP was either the date the initial salaries based on the new assessment were paid (April 28, 1978) or, at the latest, the date the retroactive differential sum was paid (July 15, 1978). Since Union Z's claim was filed on July 17, 1979, Company X asserted it was beyond the one-year limitation period stipulated by TUA Article 27, Paragraph 2, and should be dismissed.

Legal Background: TUA Article 27, Paragraph 2 – The Limitation Period

Article 27, Paragraph 2 of the Trade Union Act states that a Labor Commission "cannot receive an application for a remedy pertaining to an act that occurred more than one year prior to the date of the act (or, for a continuing act, the date of its termination)." This one-year period is generally interpreted as an exclusion period (joseki kikan).

The legislative intent behind this limitation, introduced in a 1952 TUA amendment, was twofold:

- Evidentiary Difficulties: For incidents over a year old, evidence collection and understanding the factual circumstances become exceedingly difficult for the Labor Commission during its investigation and hearings.

- Stability of Labor Relations: Issuing orders long after the fact could potentially disrupt, rather than stabilize, labor relations, and the practical benefit of such late orders might be minimal.

In the context of discriminatory wage assessments, which often involve subjective performance evaluations and non-transparent processes, the interpretation of "continuing act" becomes critical, as union members may not immediately realize that discrimination has occurred.

Rulings of the Labor Commission and Lower Courts

- Commission Y (Aomori Prefectural Labor Commission): Found that wage disparities existed between Union Z members and non-union members, concluding that this constituted ULP under TUA Article 7(1) (disadvantageous treatment) and 7(3) (domination/interference). It ordered Company X to redo the evaluations and pay the wage differentials. The Labor Commission, in determining the ULP, reportedly used a statistical "mass observation method" (大量観察方式 - tairyō kansatsu hōshiki) to infer discrimination from the wage gaps.

- District Court (Aomori District Court): Regarding the limitation period, it held that "a ULP claim is timely if filed within one year from the wage payment of the month preceding the next wage assessment or wage increase decision." It largely upheld Commission Y's orders, except for a part related to position allowances.

- High Court (Sendai High Court): While it modified some aspects of the District Court's judgment, it maintained the lower court's interpretation regarding the timeliness of the ULP claim.

Company X appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily challenging the interpretation of the limitation period and the "continuing act" concept.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Defining "Continuing Act" in Wage Discrimination

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal concerning the First Case (1978 wage revision), upholding the lower courts' view that the ULP claim was timely.

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of Annual Wage Assessments: Company X's annual performance appraisals (考課査定 - kōka satei) determine the rating values that form the basis for employees' monthly wage amounts for the entire subsequent year.

- Realization of Discriminatory Intent: If an employer, during such an appraisal, gives union members lower ratings because of their union membership compared to other employees, this discriminatory intent is concretely realized through the actual payment of wages based on these lower ratings.

- Integral Nature of Assessment and Payment: The discriminatory appraisal and the subsequent monthly wage payments based on that appraisal should be viewed integrally as constituting a single unfair labor practice.

- ULP Continues as Long as Discriminatory Wages are Paid: Consequently, as long as wages based on the discriminatory appraisal are being paid, the unfair labor practice is considered to be continuing.

- Calculating the Limitation Period: Therefore, a ULP claim seeking correction of such wage discrimination based on a specific annual appraisal is timely under TUA Article 27, Paragraph 2, if it is filed within one year from the date of the last wage payment made based on that particular discriminatory annual appraisal.

Applying this reasoning, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment that Union Z's ULP claim for the 1978 wage revision was filed within the permissible period. The appeal regarding the Second Case (1979 and 1980 wage revisions) was dismissed because Company X did not submit a statement of reasons for appeal for that portion of the case.

Analysis and Significance

The Beniya Shoji decision is a landmark ruling for its clear interpretation of "continuing act" in the context of ULP claims related to discriminatory wage assessments.

- Settling Conflicting Views: This was the first Supreme Court decision to directly address this specific issue, providing a definitive stance amidst previously divided opinions among Labor Commissions and legal scholars. The PDF commentary outlines three main pre-existing views on whether discriminatory appraisals and subsequent payments constitute a "continuing act":

- Separate Acts View: The appraisal is a one-time, completed act, and subsequent payments are merely its effects, not a continuation of the ULP. (Example: Uchida Yoko case, CLC 1971)

- Blueprint/Execution View: The appraisal is a "blueprint" for discrimination, and the wage payments are the execution of that blueprint, making them an inseparable and continuous ULP. (Example: IBM Japan case, Kanagawa LRC 1976)

- Continuing Omission View: As long as the wage differential due to the discriminatory appraisal is not paid (i.e., the correct amount is omitted), the ULP continues. (Example: Radio Kansai case, Hyogo LRC 1976)

The Supreme Court's decision in Beniya Shoji aligns most closely with the "Blueprint/Execution View," treating the discriminatory assessment and the resulting payments as an integrated whole.

- Extended Period for ULP Claims: By defining the ULP as continuing until the last wage payment based on a specific discriminatory annual appraisal, the ruling provides a significantly longer window for employees and unions to file ULP claims compared to if the period started from the date of the appraisal itself or the first discriminatory payment. This is crucial because discovering and proving such discrimination can take time.

- Balancing Statutory Aims: The decision strikes a balance between the objectives of the TUA Article 27(2) limitation period (ensuring evidentiary reliability and stable labor relations) and the overarching goal of the ULP system to protect workers from anti-union discrimination.

- Unresolved Issues and Future Considerations:

- Cumulative Discrimination Over Multiple Years: The Beniya Shoji case dealt with a ULP claim related to a single year's wage assessment. The PDF commentary notes that it remains an open question whether a series of discriminatory annual appraisals across multiple years could be treated as one single, overarching "continuing act." Some legal scholars argue this might be possible under "special circumstances," such as when the annual assessments are demonstrably interrelated and form part of a consistent discriminatory pattern. Others, however, have cautioned against overly broad interpretations, emphasizing that each year's assessment might still be a distinct act unless clear linkage is proven.

- Application to Promotion and Other Forms of Discrimination: While this case specifically addressed wage discrimination stemming from annual appraisals, its fundamental logic – that an initial discriminatory decision and its ongoing implementation can form an integral ULP – has influenced thinking in other areas. The PDF commentary mentions that lower courts have applied a similar framework to cases of discriminatory promotion decisions that are made annually.

- Maintaining the Limitation Period's Integrity: The PDF commentary also refers to a more recent Tokyo District Court decision (Meiji University case, 2018) which, while acknowledging Beniya Shoji, reiterated that the interpretation of "continuing act" must still respect the underlying purpose of the one-year limitation period. This suggests a need to carefully examine the specific intent, connection, and temporal proximity of acts before broadly categorizing them as "continuing."

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Beniya Shoji case marked a significant step in clarifying the application of the statute of limitations for unfair labor practice claims involving ongoing wage discrimination. By holding that a discriminatory annual wage assessment and the subsequent series of monthly payments based on it constitute a single, "continuing act," the Court provided a more practical and protective timeframe for workers and unions to seek remedies. This interpretation ensures that the one-year limitation period under TUA Article 27(2) does not unduly hinder redress for discrimination that unfolds over time, while still acknowledging the need for claims to be brought within a reasonable period after the harm ceases. The ruling remains a key precedent in navigating ULP claims related to systematic wage discrimination.