Defining a "Business Transfer" in Japanese Corporate Law: The 1965 Supreme Court Landmark on Shareholder Approval

Judgment Date: September 22, 1965

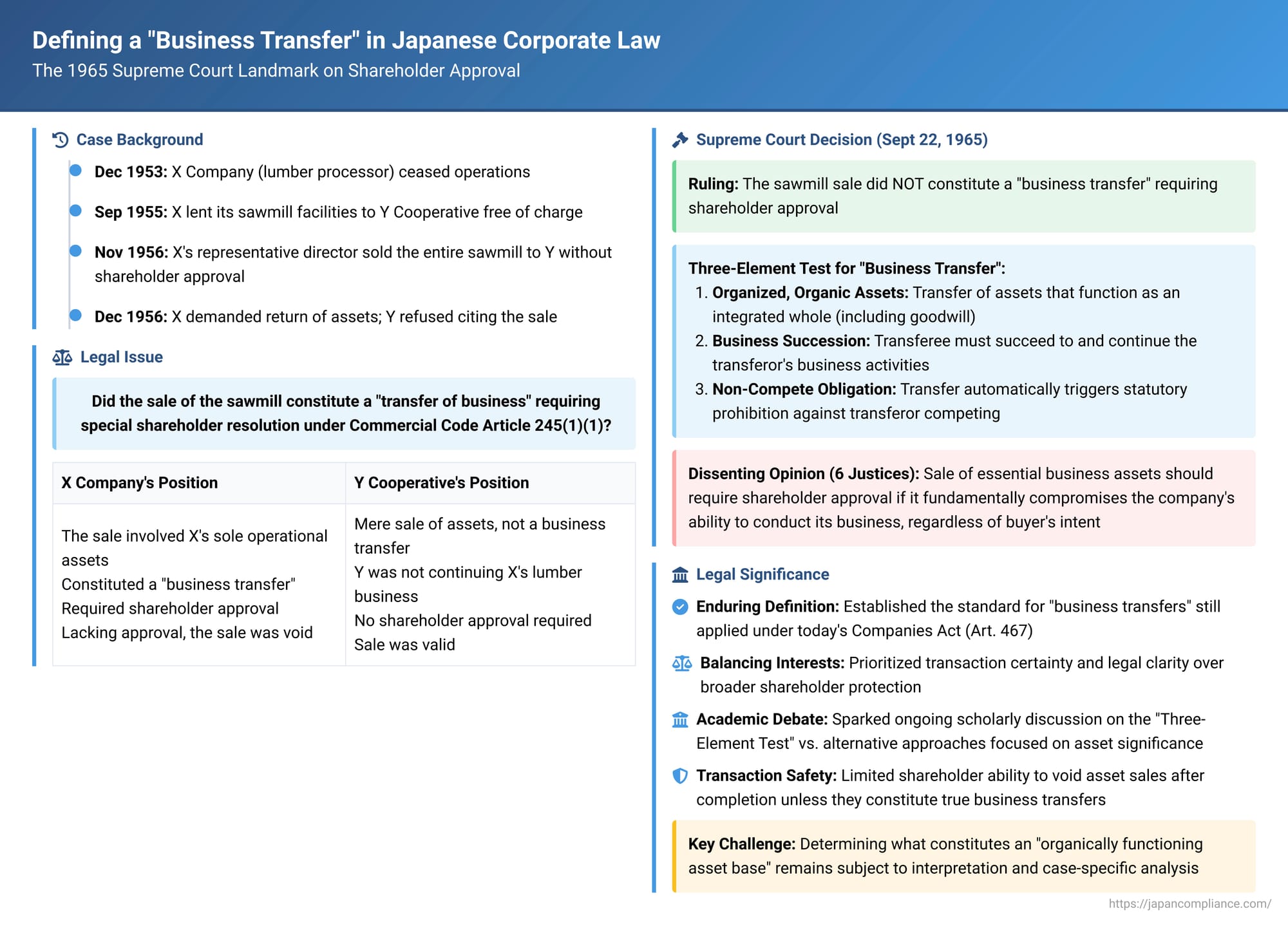

The transfer of a company's entire business, or a substantial portion of it, is a momentous event with profound implications for the company's future and its shareholders. Consequently, Japanese corporate law has long mandated that such significant dispositions require a special resolution of the shareholders' meeting. A pivotal 1965 Grand Bench decision by the Supreme Court of Japan grappled with the precise definition of what constitutes a "transfer of business" triggering this requirement, drawing a crucial distinction between the sale of mere business assets and the transfer of an integrated, operational business undertaking. This ruling continues to be a cornerstone in interpreting such transactions today.

The Factual Dispute: A Sawmill Sale and a Question of Authority

The case involved X Kabushiki Kaisha (X Company), a company primarily engaged in lumber processing and the sale of its products. Facing financial difficulties, X Company ceased its operations in December 1953. In September 1955, X Company entered into an agreement with Y Cooperative, lending its sawmill – comprising land, buildings, and essential transport rail infrastructure – to Y Cooperative free of charge. A key condition of this loan was that Y Cooperative would return these assets whenever X Company required them. Y Cooperative subsequently took possession and began using these facilities.

The pivotal event occurred in November 1956. The representative director of X Company, acting without obtaining either a special resolution from X Company's shareholders' meeting or a resolution from its board of directors, purported to sell the entire sawmill complex (land, buildings, machinery, and tools) to Y Cooperative. Y Cooperative duly paid the agreed purchase price.

Shortly thereafter, in December 1956, X Company demanded that Y Cooperative return the sawmill assets as per their initial loan agreement. Y Cooperative refused, asserting that it now owned the assets due to the sale. This led X Company to file a lawsuit seeking the return of the property and related declarations. Y Cooperative, in turn, filed a counterclaim, seeking confirmation of its ownership based on the sale.

The lower courts sided with Y Cooperative, upholding the validity of the sale. X Company appealed to the Supreme Court. Its central argument was that the sawmill assets sold to Y Cooperative constituted its sole and entire operational assets. Therefore, their sale amounted to a "transfer of all or an important part of the business" as defined in Article 245, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the then-applicable Commercial Code (a provision corresponding to what is now Article 467, Paragraph 1, Items 1 and 2 of the Companies Act). Since this alleged transfer of business lacked the statutorily required special resolution of X Company's shareholders, X Company argued the sale contract was void.

The Supreme Court's Majority Opinion: The Three-Pronged Definition

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment dated September 22, 1965, ultimately dismissed X Company's appeal, finding that the sale in question did not constitute a "transfer of business" that would necessitate a special shareholder resolution. In doing so, the majority laid down a highly influential definition:

The Court stated that a "transfer of business" requiring a special resolution under the then-Commercial Code Article 245, Paragraph 1, Item 1 is identical in meaning to the "transfer of business" (営業譲渡 - eigyō jōto) referred to in Article 24 and subsequent articles of the Commercial Code (which govern general business transfers, now found in Commercial Code Article 15 et seq. and Companies Act Article 21 et seq.).

The majority elaborated that this means:

- Transfer of Organized, Organically Functioning Assets: The transaction must involve the transfer of all or an important part of assets that are organized for a specific business purpose and function as an organic, integrated whole. This includes not only tangible assets but also intangible valuable factual relationships, such as customer connections (goodwill).

- Succession to Business Activities: Through this transfer, the transferee (buyer) must succeed to and carry on all or an important part of the business activities that the transferor (seller) had been conducting using those assets.

- Automatic Non-Compete Obligation: As a legal consequence of such a transfer, the transferor company automatically becomes subject to a statutory non-compete obligation as stipulated in Article 25 of the then-Commercial Code (which prevents the transferor from engaging in the same business within a certain area for a certain period).

The majority reasoned that the legislature used the established term "transfer of business" in Article 245(1)(1) precisely because it was a pre-existing legal concept with a relatively clear meaning. The intent was to impose the stringent requirement of a special shareholder resolution not for every sale of business assets, but only for those more significant transactions that qualified as a true transfer of the business undertaking itself. This approach, the majority believed, aimed to promote legal clarity and the safety of transactions.

The Court found that adopting X Company's broader interpretation (which would include the sale of key assets that effectively crippled the business, regardless of operational succession) would contradict the plain wording of the statute, undermine legal stability, and make the validity of such transactions dependent on the transferor's internal circumstances, which might not be apparent to the transferee, thereby harming transaction safety.

While the majority did not explicitly detail how these principles applied to X Company's specific facts beyond rejecting its claim, the High Court (whose decision was effectively upheld) had found that Y Cooperative did not intend to take over X Company's lumber business (which was outside Y Cooperative's own business purposes). Instead, Y Cooperative intended to use the real estate for its own distinct activities (as a marketplace for timber and processed wood products from its members) and had only purchased the machinery and tools out of consideration for X Company, which would have struggled to dispose of them otherwise. This suggests the transaction was viewed by the lower courts, and implicitly by the Supreme Court majority, as a sale of disaggregated assets rather than the transfer of an ongoing, organic business unit.

The Dissenting Voices: A Strong Focus on Shareholder Protection

The Grand Bench decision was not unanimous; it included two significant dissenting opinions, collectively supported by six justices. These dissents offered a different perspective, primarily emphasizing shareholder protection:

The dissenting justices argued that the definition of "transfer of business" for the purpose of requiring a special shareholder resolution (Article 245(1)(1)) should not be rigidly tied to the definition used for general business transfers in Article 24 et seq. of the Commercial Code. Specifically, they contended that elements like the "succession to business activities" by the transferee or the automatic imposition of a non-compete obligation should not be strict requirements.

Their core argument was that if the sale of essential business assets – such as the sole factory of a manufacturing company, as in X Company's case – fundamentally compromises or terminates the company's ability to conduct its intended business, then such a sale has a profound impact on the company's existence and purpose. In such circumstances, it should be treated as equivalent to a transfer of the business itself, thus necessitating a special shareholder resolution to protect the interests of the company and its shareholders. This should hold true regardless of whether the buyer intends to continue the exact same business activity.

One dissenting opinion drew a parallel with Japan's Antimonopoly Act, which at the time regulated business acquisitions and appeared to treat "transfer of business" and "acquisition of major fixed assets for business" in a similar vein. The dissenters expressed concern that the majority's narrow definition could allow a representative director to unilaterally dispose of a company's entire operational capacity without shareholder consent, provided the buyer had a different purpose for the assets. They also countered the majority's transaction safety concerns by arguing that for significant assets like a factory, a potential buyer could generally ascertain the asset's importance to the selling company's operations by reviewing publicly available financial statements.

The Enduring Legacy and Ongoing Debate

The 1965 Grand Bench decision has had a lasting impact on Japanese corporate law, though the debate surrounding its interpretation continues.

- Relevance to the Current Companies Act: Although the term "営業" (eigyō - business/enterprise) in the old Commercial Code has largely been replaced by "事業" (jigyō - business/undertaking) in the current Companies Act (e.g., Article 467 governing business transfers), this change is generally considered to be for terminological consistency rather than a substantive alteration of the underlying legal concepts. Therefore, the principles enunciated in the 1965 Supreme Court ruling are still widely regarded as applicable to the interpretation of "business transfers" under the current Companies Act.

- The "Three-Element Test": The majority opinion is often understood as establishing a three-element test for what constitutes a "transfer of business" requiring special shareholder approval: (1) the transfer of organized, organically functioning assets (including goodwill); (2) the succession to the transferor's business activities by the transferee; and (3) the automatic legal imposition of a non-compete duty on the transferor. Subsequent Supreme Court decisions have reiterated this formulation, and it remains a common point of reference in lower court judgments. For instance, one case found that the sale of a golf course's real estate and movables was not a business transfer because, among other things, club memberships were not transferred, indicating no succession of the core business activity. Conversely, another case involving the transfer of factory premises, equipment, and a clear handover of business operations was deemed a business transfer.

- Scholarly Interpretations and Debate: The academic world has engaged in extensive discussion about the precise meaning and requirements of the 1965 ruling:

- Some scholars maintain the traditional understanding that all three elements identified by the majority are indispensable requirements. This view emphasizes legal consistency and the clarity it offers for transaction safety.

- Others argue that the non-compete obligation (element 3) is a legal consequence of a business transfer, not a definitional prerequisite.

- A view closer to the dissenting opinions suggests that neither the succession of business activities (element 2) nor the non-compete obligation (element 3) should be strict requirements. This perspective prioritizes shareholder protection when a disposition of assets has a critical impact on the transferor company's operational capacity.

- Currently, a widely supported scholarly view (often described as the "Fourth View") posits that a business transfer primarily involves the transfer of an "organic, functional, organized asset base" (element 1). Elements 2 and 3 are not seen as essential requirements for all cases. However, unlike the more expansive view of the dissenters, this theory holds that merely transferring important individual assets is insufficient if those assets do not form an organically integrated business unit. This view seeks to protect shareholders when the company's fundamental operational structure is affected, without necessarily requiring that the transferee continue the exact same activities. For example, the transfer of business assets along with essential know-how might qualify, even without the transfer of customer lists or employees.

- The Challenge of "Organic Unity": A persistent difficulty with several of these interpretations is the inherent ambiguity in determining what constitutes an "organically functioning asset base" or "organic unity." This ambiguity can pose risks to transaction safety.

- Addressing Transaction Safety - "Relative Invalidity": To mitigate these risks, some scholars have proposed the concept of "relative invalidity" (sōtaiteki mukō). Under this theory, while a business transfer made without the required special shareholder resolution would be void, the transferor company could not assert this invalidity against a transferee who acquired the business in good faith and without gross negligence as to the need for such a resolution. However, if the concept of "organic unity" itself is unclear, determining the transferee's good faith or gross negligence regarding this specific legal requirement also becomes challenging, potentially limiting the effectiveness of the relative invalidity doctrine in fully securing transactions.

- Balancing Shareholder Protection and Transaction Safety: The ongoing debate ultimately revolves around finding the appropriate balance between protecting the legitimate interests of the transferor company's shareholders and ensuring the certainty and safety of commercial transactions. Additionally, considerations of the proper allocation of authority between the board of directors and the shareholders' meeting play a role.

- "Important Part of the Business" and Simplified Transfers: The Companies Act (Article 467, Paragraph 1, Item 2) also requires a special shareholder resolution for the "transfer of an important part of the business." Determining what constitutes an "important part" can be complex. To provide some clarity and ease the burden for less significant transactions, the Companies Act introduced a "simplified business transfer" mechanism: if the book value of the assets being transferred is one-fifth (or a lower threshold if stipulated in the articles of incorporation) or less of the transferor company's total assets, a shareholder resolution is not required. While exceeding this threshold does not automatically classify a transfer as "important," in practice, companies often opt to seek shareholder approval if this quantitative benchmark is surpassed.

Conclusion

The 1965 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision remains a seminal judgment in Japanese corporate law, establishing an influential (though continuously debated) framework for defining a "transfer of business" that necessitates special shareholder approval. By focusing on the transfer of an integrated, operational business unit intended to be continued by the transferee, coupled with the legal consequence of a non-compete obligation, the majority opinion prioritized legal certainty and transaction safety. However, the strong dissenting opinions and subsequent scholarly discourse have kept alive the critical debate about ensuring robust shareholder protection when asset dispositions fundamentally alter a company's operational capacity or existence. This enduring tension continues to shape the understanding and application of rules governing major corporate transactions in Japan.