Defense Counsel vs. Juvenile Attendant: Japan Supreme Court Sets Boundary in 1957 Ruling

1957 Supreme Court ruling clarified that defense counsel status doesn't automatically continue as 'attendant' in Japan's juvenile proceedings.

TL;DR

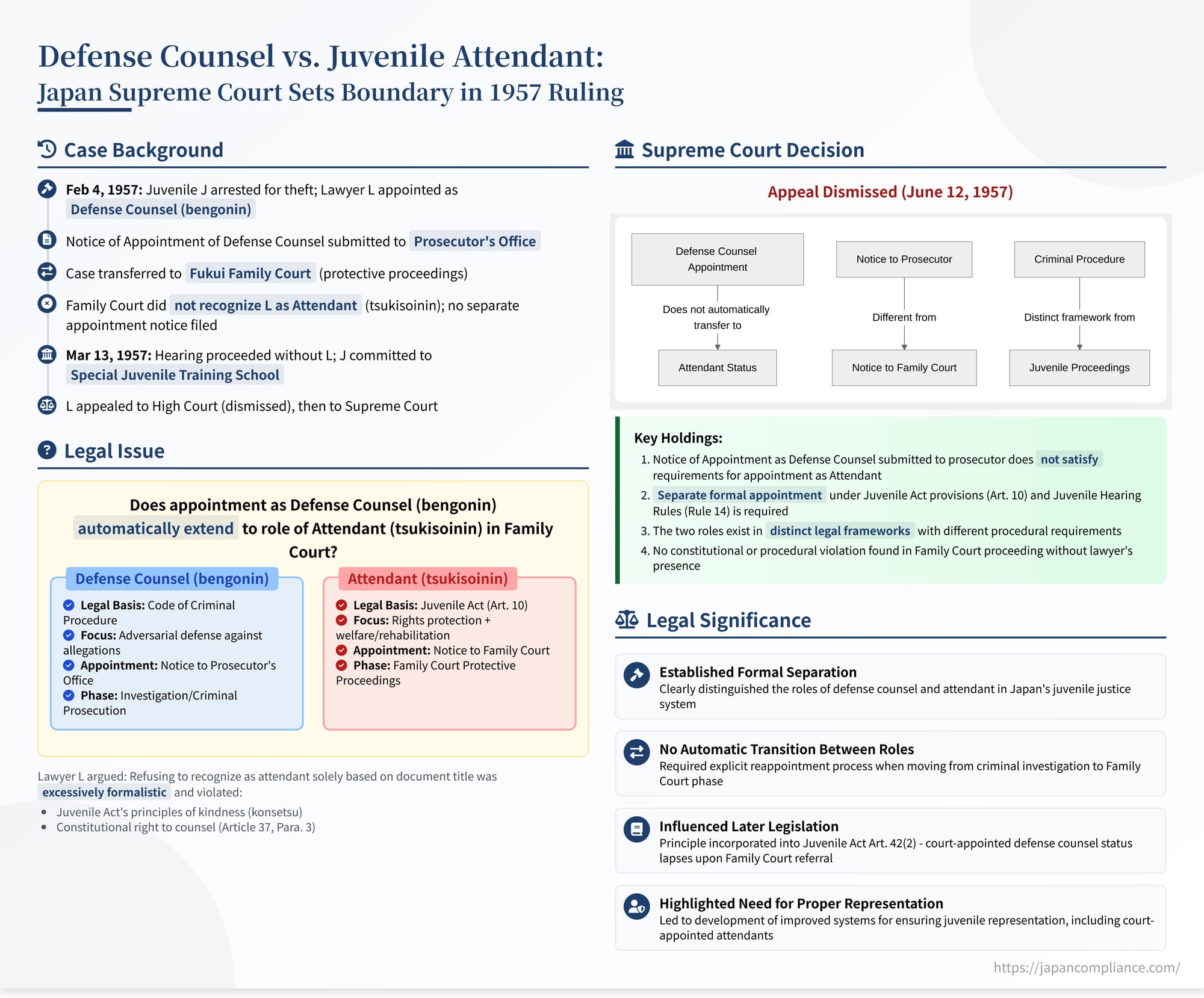

In 1957, Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that a lawyer appointed as bengonin (defense counsel) during a criminal investigation does not automatically become the tsukisoinin (attendant) in subsequent Family Court juvenile proceedings. A separate, formal appointment is legally required, a principle that still shapes juvenile justice practice and legislation today.

Table of Contents

- Case Background: Representation Denied in Family Court

- The Legal Distinction: Bengonin vs. Tsukisoinin

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: No Automatic Transition

- Rationale, Debate, and Subsequent Developments

- Significance of the 1957 Ruling

Japan's system for handling juvenile delinquency operates on a distinct track compared to adult criminal procedure. While initial investigations into suspected offenses by minors often involve police and prosecutors, similar to adult cases, the subsequent proceedings typically shift to the Family Court. This court focuses not just on fact-finding but primarily on the juvenile's welfare, protection, and rehabilitation, employing measures distinct from adult criminal sanctions. This procedural shift raises important questions about legal representation. Does a lawyer appointed as "defense counsel" (bengonin) during the initial investigation phase automatically continue to represent the minor in the Family Court phase, where the lawyer's role is termed "attendant" (tsukisoinin)? A foundational decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 12, 1957, addressed this precise issue, establishing a clear demarcation between these two roles.

Case Background: Representation Denied in Family Court

The case involved a juvenile, J, who was arrested on suspicion of theft. During the investigation phase, on February 4, 1957, lawyer L was appointed as J's defense counsel. A formal "Notice of Appointment of Defense Counsel" (bengonin sennin todoke), signed by both J and L, was duly submitted to the Fukui District Public Prosecutors Office on February 5th.

Following the investigation, the prosecutor's office referred J's case to the Fukui Family Court, initiating protective proceedings (hogo jiken) under the Juvenile Act. The notice appointing L as defense counsel was included in the case file transferred to the Family Court. However, neither J nor L submitted a separate document explicitly appointing L as J's "attendant" (tsukisoinin) for the Family Court proceedings, as stipulated by the Juvenile Hearing Rules.

Consequently, the Fukui Family Court did not formally recognize L as J's attendant. It did not notify L of the scheduled hearing date (shinpan kijitsu) and proceeded with the hearing without L being present. On March 13, 1957, the Family Court issued a disposition ordering J to be committed to a Special Juvenile Training School (tokubetsu shōnen'in), a secure facility for juveniles deemed to have serious delinquent tendencies.

Lawyer L, acting on J's behalf, appealed this disposition to the Nagoya High Court (Kanazawa Branch), arguing it was significantly inappropriate. The High Court dismissed the appeal. L then filed a further appeal (a re-appeal or saikōkoku) to the Supreme Court. The primary ground for this final appeal was procedural: L argued that the Family Court's refusal to recognize L as the attendant and allow participation in the hearing – merely because the submitted document was titled "Notice of Appointment of Defense Counsel" rather than "Notice of Appointment of Attendant" – was excessively formalistic. L contended this violated the Juvenile Act's principles emphasizing the juvenile's welfare and requiring proceedings to be handled with kindness (konsetsu), and also infringed upon the constitutional right to counsel (Article 37, Paragraph 3).

The Legal Distinction: Bengonin vs. Tsukisoinin

Understanding the Supreme Court's decision requires appreciating the distinct legal roles of a bengonin and a tsukisoinin:

- Defense Counsel (Bengonin): This role exists within the framework of the Code of Criminal Procedure, primarily during the investigation and potential criminal prosecution phases. The focus is adversarial – defending the suspect or accused against criminal allegations. In the adult system, under Article 32(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, a lawyer appointed as defense counsel before indictment generally continues in that role automatically into the trial phase.

- Attendant (Tsukisoinin): This role is specific to Family Court proceedings under the Juvenile Act. While it encompasses protecting the juvenile's legal rights and ensuring due process (similar to a defense counsel), its scope is often considered broader. The attendant may also play a role in cooperating with the court to determine the most appropriate protective measures for the juvenile's rehabilitation and welfare. This can sometimes involve activities more akin to social work or casework. Critically, formal appointment as an attendant requires submitting a specific notice to the Family Court, as per Article 10 of the Juvenile Act and Rule 14(2) of the Juvenile Hearing Rules. While lawyers are automatically qualified to be attendants without needing special court permission (unlike non-lawyer attendants), the formal appointment step remains.

The Supreme Court's Decision: No Automatic Transition

The Supreme Court dismissed J's (and L's) re-appeal, firmly rejecting the argument that appointment as defense counsel automatically confers attendant status in Family Court.

Formal Appointment Required:

The Court's core reasoning was straightforward:

- The "Notice of Appointment of Defense Counsel" was submitted to the prosecutor during the investigation phase for the specific role of bengonin.

- Acting as an attendant (tsukisoinin) in Family Court proceedings requires a separate appointment process under the distinct provisions of the Juvenile Act (Art. 10) and its associated rules (Rule 14).

- Therefore, the prior appointment as defense counsel, documented by a notice filed with the prosecutor, does not automatically satisfy the requirements for appointment as an attendant in Family Court. Lawyer L, despite the prior role, was not formally appointed as J's attendant according to the applicable juvenile procedure rules.

Procedural Arguments Dismissed:

The Court characterized L's arguments about constitutional violations and procedural failures as essentially derivative of the central claim that L should have been automatically recognized as the attendant. Since the Court rejected this premise, the related arguments regarding improper procedure were deemed insufficient grounds for a re-appeal. The Court noted that the arguments were, in substance, new challenges to the Family Court's original procedure, not flaws in the High Court's decision dismissing the initial appeal, making them inappropriate for the re-appeal stage.

Rationale, Debate, and Subsequent Developments

The 1957 decision sided with the view (the "Negative view" in subsequent commentary) that emphasized the distinct legal frameworks, the formal requirements for appointing an attendant, and the potentially different nuances of the attendant's role compared to a purely adversarial defense counsel. The need to confirm the lawyer's and the juvenile's specific intent to continue the relationship in the Family Court setting under the attendant framework was likely also a consideration.

However, the decision drew criticism. Some argued that given the Family Court's awareness of L's prior involvement (the notice was in the file) and the Juvenile Act's emphasis on conducting proceedings with "kindness," the court could, or perhaps should, have proactively inquired whether L intended to continue representing J as an attendant.

This ruling established a clear legal boundary but highlighted a potential gap in continuous representation. While legally distinct, the defense counsel and attendant roles often require similar skills and knowledge, and continuity can be highly beneficial for the juvenile.

Later developments and practices have somewhat addressed the practical issues raised by this decision, even while upholding its core legal principle:

- Legislative Confirmation: When Japan later introduced a system for court-appointed defense counsel (kokusen bengonin) for suspects (not just defendants), the Juvenile Act was amended (adding Article 42, Paragraph 2). This amendment explicitly states that a court-appointed defense counsel's status lapses upon the case's referral to Family Court, directly reflecting the principle established in the 1957 decision – no automatic transition.

- Court-Appointed Attendants: Japan subsequently introduced and expanded systems for court-appointed attendants (kokusen tsukisoinin) in certain serious juvenile cases (e.g., where the juvenile is detained or facing severe charges).

- Practical Facilitation: Although automatic transition is not legally mandated, Family Courts in practice often facilitate continuity. If a juvenile had court-appointed defense counsel during the investigation, and an attendant is needed in Family Court, courts frequently appoint the same lawyer as the attendant, provided the lawyer files the necessary request or the court exercises its discretion to appoint them. Similarly, if a lawyer was privately retained as defense counsel, courts often prompt them to file the formal attendant appointment notice if they intend to continue.

Significance of the 1957 Ruling

This relatively brief 1957 decision remains significant for several reasons:

- Established Formal Separation: It clearly established that, under Japanese law, the role of defense counsel (bengonin) in the criminal procedure phase is legally distinct from the role of attendant (tsukisoinin) in the Family Court's juvenile protection phase.

- No Automatic Carry-Over: It confirmed that formal appointment as the former does not automatically grant status as the latter; separate procedural requirements under the Juvenile Act must be met.

- Influenced Later Legislation: Its principle directly influenced the drafting of Juvenile Act Article 42(2) concerning the lapsing of court-appointed defense counsel status upon Family Court referral.

- Highlighted Need for Attendant System: By clarifying the lack of automatic carry-over, the decision implicitly highlighted the importance of the attendant role and potentially contributed to the later development of systems for ensuring attendant representation, including court appointments.

While modern practice often aims for continuity in representation for the juvenile's benefit, this 1957 Supreme Court ruling established the enduring legal principle that the transition from defense counsel in the investigation phase to attendant in the Family Court requires a distinct, formal step under the procedures governing juvenile justice.

- Understanding Compensation for Detention in Japanese Juvenile Cases: The 1991 Supreme Court Decision

- How Much Re‑Investigation on Remand? Japan Supreme Court Limits Scope in Juvenile Case (July 11 2008 Decision)

- The Witness as Evidence: How Japan's High Court Ruled on the Crime of Hiding a Witness

- Juvenile Act (English Translation) – Japanese Law Translation

- Judgments of the Supreme Court of Japan (English Interface)