Defective Work, Unpaid Price: When Can a Customer Withhold Full Payment in Japan?

Date of Judgment: February 14, 1997

Case Name: Claim for Construction Price

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

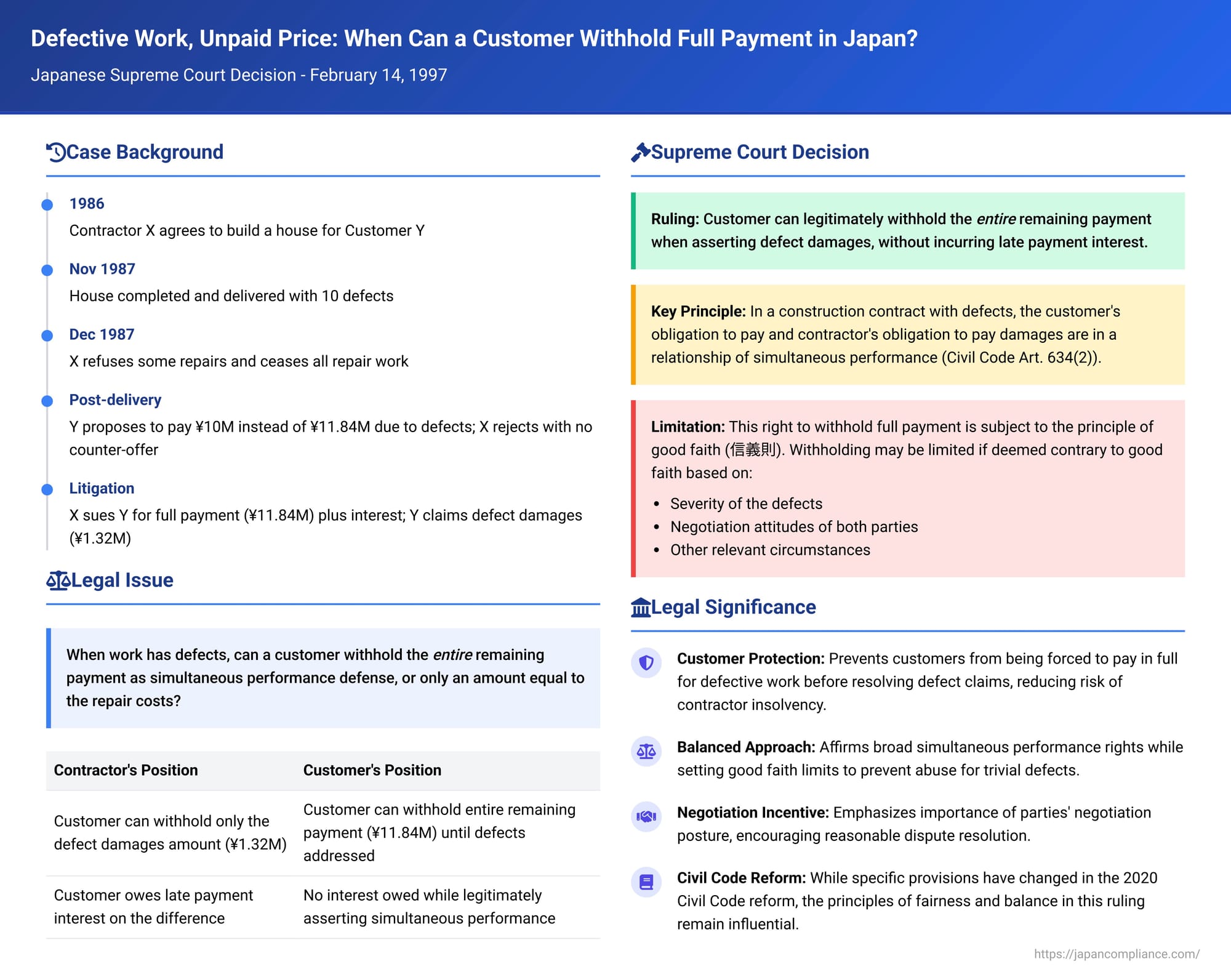

In construction projects, disputes often arise when the completed work has defects. The customer, faced with imperfections, may have a claim for repairs or monetary damages. Simultaneously, the contractor will be seeking payment of the remaining contract price. This scenario begs a critical question: can the customer withhold the entire outstanding payment, even if their damage claim is for a lesser amount, until the defect issue is resolved? Or are they only entitled to withhold an amount equivalent to their damages? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from February 14, 1997, tackled this issue, clarifying the application of the defense of "simultaneous performance" in such situations under the then-prevailing Civil Code.

A House Built with Flaws, A Payment Dispute: The Factual Setting

The case involved a contract for the construction of a residential house:

- The Contract and Completion: In 1986, X (the contractor) agreed to build a house for Y (the customer). The house was completed and delivered to Y by the end of November 1987. After an initial contract price, additional works, and a mid-term payment by Y, the remaining balance owed to X was approximately ¥11.84 million.

- Discovery of Defects: Upon inspection at the time of delivery, ten defects were found in the completed house. The cost to repair these defects was later assessed at approximately ¥1.32 million.

- Failed Negotiations: Y requested X to carry out the necessary repairs. X, however, refused to perform some of them and eventually ceased all repair work around December 10, 1987. Subsequently, Y proposed to settle the entire matter by paying ¥10 million (implicitly suggesting a reduction from the ¥11.84 million balance to account for the defects). X rejected this proposal but did not offer any counter-proposal regarding the repair costs or a suitable price reduction.

- Litigation: X sued Y for the full remaining contract price of approximately ¥11.84 million, plus substantial contractual late payment interest (calculated at a rate of 0.1% of the unpaid amount per day from the day after delivery).

Y, in defense, asserted a claim for damages in lieu of defect repair (for the ~¥1.32 million) and invoked the defense of simultaneous performance. Y argued that their obligation to pay the remaining contract price was conditional upon X fulfilling its obligation to compensate for the defects, and thus Y should not be liable for late payment interest while this standoff persisted. - Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court recognized Y's damages claim at ~¥1.32 million. It ordered Y to pay X the remaining contract price in exchange for X paying Y the damages amount (this is known as a "barter performance judgment" - 引換給付判決, effectively creating a simultaneous performance situation). Critically, the court dismissed X's claim for late payment interest. (Following this, X provisionally enforced the judgment by offering its counter-performance – the damages – and Y made the corresponding payment of the balance).

- The High Court upheld the first instance decision, meaning X lost again on the late interest claim. X's attempts to declare a set-off (offsetting the damages against the price) at various stages were not deemed effective by the courts.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that Y's right to claim simultaneous performance should be limited to the actual amount of the damages. X contended that Y should have paid the difference between the remaining price and the damages immediately and should be liable for late payment interest on that difference.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the core of the lower courts' decisions that X was not entitled to late payment interest for the period Y withheld payment pending resolution of the defect claim.

Core Rulings of the Supreme Court:

- Simultaneous Performance as a General Rule (under Former Civil Code Art. 634(2)):

The Court held that in a contract for work, if the completed work has defects and the customer claims monetary damages in lieu of repair, and assuming neither party has validly effected a set-off of these claims, then the customer's obligation to pay the contract price and the contractor's obligation to pay damages for the defects are generally in a relationship of simultaneous performance. This was based on the then-existing Article 634, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, which made provisions for simultaneous performance in sales applicable to such situations in contracts for work.

Consequently, one party (e.g., the customer) can refuse to perform their obligation (payment of the full price) until the other party (the contractor) performs their counter-obligation (payment of damages or, by implication, remedy of defects if still possible and demanded). During the period this standoff is legitimately maintained, the refusing party is not considered to be in default and thus does not incur liability for late performance (e.g., late payment interest). - The Good Faith Limitation:

This right to assert simultaneous performance for the entire remaining contract price is not absolute. The Court introduced an important qualification: if, considering the actual severity of the defects, the negotiation attitudes of both parties, and other relevant circumstances, it would be contrary to the principle of good faith (信義則 - shingisoku) for the customer to refuse payment of the entire outstanding remuneration based on their (potentially much smaller) damages claim, then the scope of the simultaneous performance defense may be limited. - Not Necessarily Limited to the Offset Amount:

Crucially, the Court did not agree with X's argument that the simultaneous performance defense is automatically limited to the amount where the two claims would offset each other (i.e., that Y should only have withheld ~¥1.32 million and paid the balance immediately). The right to withhold payment can, in principle, extend to the entire remaining contract price, provided exercising this right is not a breach of good faith. - Relevance of Triviality of Defects (Former Civil Code Art. 634(1) Proviso):

The Court also touched upon the proviso in former Article 634, Paragraph 1, which stated that if defects were not material and their repair would involve excessive cost, the customer could only claim damages, not demand repair. The Supreme Court clarified that even in such situations (where only damages can be claimed for non-material but costly-to-repair defects), it doesn't automatically mean simultaneous performance for the full remuneration is always affirmed. Other factors still need to be considered, and asserting such a defense could still be denied as contrary to good faith if the circumstances warrant. - Rationale for this Balanced Approach:

The Court explained that this interpretation is necessary to strike a fair balance. If simultaneous performance for the full amount were not generally recognized (subject to good faith), customers receiving defective work would be unfairly disadvantaged (e.g., forced to pay in full and then separately sue for damages, risking contractor insolvency). Conversely, if customers could always withhold the entire payment even for extremely minor or trivial defects where they were being unreasonable, it would lead to an unfair outcome for contractors.

Application to the Facts of This Case:

The Supreme Court found that, in this specific instance:

- The defects in Y's newly built house were not trivial. They included significant issues like uneven floors causing difficulties with doors and windows, substandard concrete work leading to cracks, and even a missing shed that was supposed to have been built. The repair costs (~¥1.32 million) were substantial.

- Regarding negotiation attitudes, Y had attempted to reach a settlement by proposing to pay ¥10 million of the outstanding ~¥11.84 million. X, however, rejected this proposal without offering any concrete counter-offer concerning the defect compensation amount and quickly resorted to litigation.

Considering these factors – the nature of the defects and the parties' negotiation history – the Supreme Court concluded that Y's assertion of a simultaneous performance defense for the entire remaining contract price, pending resolution of the ~¥1.32 million damages claim, was not contrary to the principle of good faith. Thus, Y was not liable for late payment interest during the period this defense was validly maintained.

Legal Landscape: Defects, Damages, and Payment

This 1997 Supreme Court ruling provided significant confirmation that, under the legal framework of the former Civil Code, a customer receiving defective work could, in many circumstances, be justified in withholding the entire remaining contract price until their claim for damages due to defects was addressed, without being penalized for the delay in payment.

The Role of Former Civil Code Article 634

The statutory backbone for this decision was former Article 634 of the Civil Code, which dealt with a contractor's warranty against defects in the completed work.

- Paragraph 1 allowed the customer to demand repair, unless the defect was trivial and repair would be disproportionately expensive (in which case, only damages could be claimed).

- Paragraph 2 allowed the customer to claim damages either instead of, or in addition to, repair. Crucially, this paragraph also stated that the Civil Code provisions concerning simultaneous performance in sales contracts (Article 533) applied mutatis mutandis (with necessary changes) to the relationship between these defect-related claims (repair or damages) and the customer's obligation to pay the contract price. This cross-reference was the direct legal basis for the Supreme Court recognizing the simultaneous performance defense.

"Weak" Simultaneous Performance to Facilitate Set-Off

Legal commentary suggests that the "simultaneous performance" relationship established under former Article 634(2) was perhaps a special, somewhat "weaker" form compared to the typical robust standoff in other bilateral contracts. Its primary function was arguably to protect the customer from being considered in default (and thus liable for delay interest) while the value of the defect claim was being ascertained and negotiated. It provided a legitimate basis for the customer to pause full payment, thereby encouraging both parties to move towards a practical resolution, often through a set-off (where the damages are deducted from the remaining price). The framers of the original Civil Code provision (Dr. Ume Kenjirō) noted that it would be harsh for a customer to either pay in full for defective work (and risk the contractor's insolvency when trying to recover damages) or to be penalized for delay if they withheld payment while legitimately disputing defects.

Importance of Negotiation Posture

The Supreme Court's explicit inclusion of "negotiation attitudes" as a key factor in assessing whether withholding full payment breaches good faith is highly significant. It serves as a judicial nudge for both contractors and customers to engage in reasonable discussions to resolve defect disputes, rather than adopting intransigent positions.

Impact of the 2017/2020 Civil Code Reforms

The Japanese Civil Code underwent major revisions, many of which came into effect in 2020. Former Article 634 was repealed, and the rules concerning a contractor's liability for non-conforming work are now primarily governed by applying (mutatis mutandis) the provisions for non-conformity in sales contracts (Article 559 of the Civil Code, which in turn applies Articles 562-564).

- Under the new Article 562, a customer (as a buyer of work) can demand repair, replacement, or, if the non-conformity is not minor, a reduction in price.

- The explicit cross-reference to the simultaneous performance provisions (Article 533) that was present in former Article 634(2) is no longer there in the same direct way for claims relating to non-conforming work.

However, the general principle of simultaneous performance for reciprocal obligations (now new Article 533) remains a fundamental part of Japanese contract law. It is widely expected by legal commentators that the spirit of the 1997 Supreme Court ruling – particularly its emphasis on fairness and protecting a customer from being penalized for withholding payment when faced with significant defects, while also guarding against bad faith by the customer – will continue to be influential. The availability of a direct claim for price reduction under the new law, for instance, naturally implies a simultaneous relationship with the payment of the (now reduced) price. The underlying equitable concerns that the 1997 judgment sought to address remain highly relevant.

Conclusion

The 1997 Supreme Court decision provided crucial protection for customers who receive defective work from contractors. It affirmed that, under the legal framework of the former Civil Code, customers could generally withhold the entire remaining contract payment until their claim for damages due to defects was resolved, without incurring penalties for delay, as long as this stance was not taken in bad faith. This ruling highlighted the importance of the contractor addressing defects or compensating for them before being entitled to the full final payment. While the specific statutory provisions have since been reformed, the core principles of fairness, the need to balance the interests of both parties, and the encouragement of reasonable negotiation in resolving defect disputes continue to shape Japanese contract law.