Defective Notice to Other Shareholders? You Can Still Sue to Cancel the Resolution, Says Japan's Supreme Court

Judgment Date: September 28, 1967

Case: Action for Cancellation of Shareholders' Meeting Resolution (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

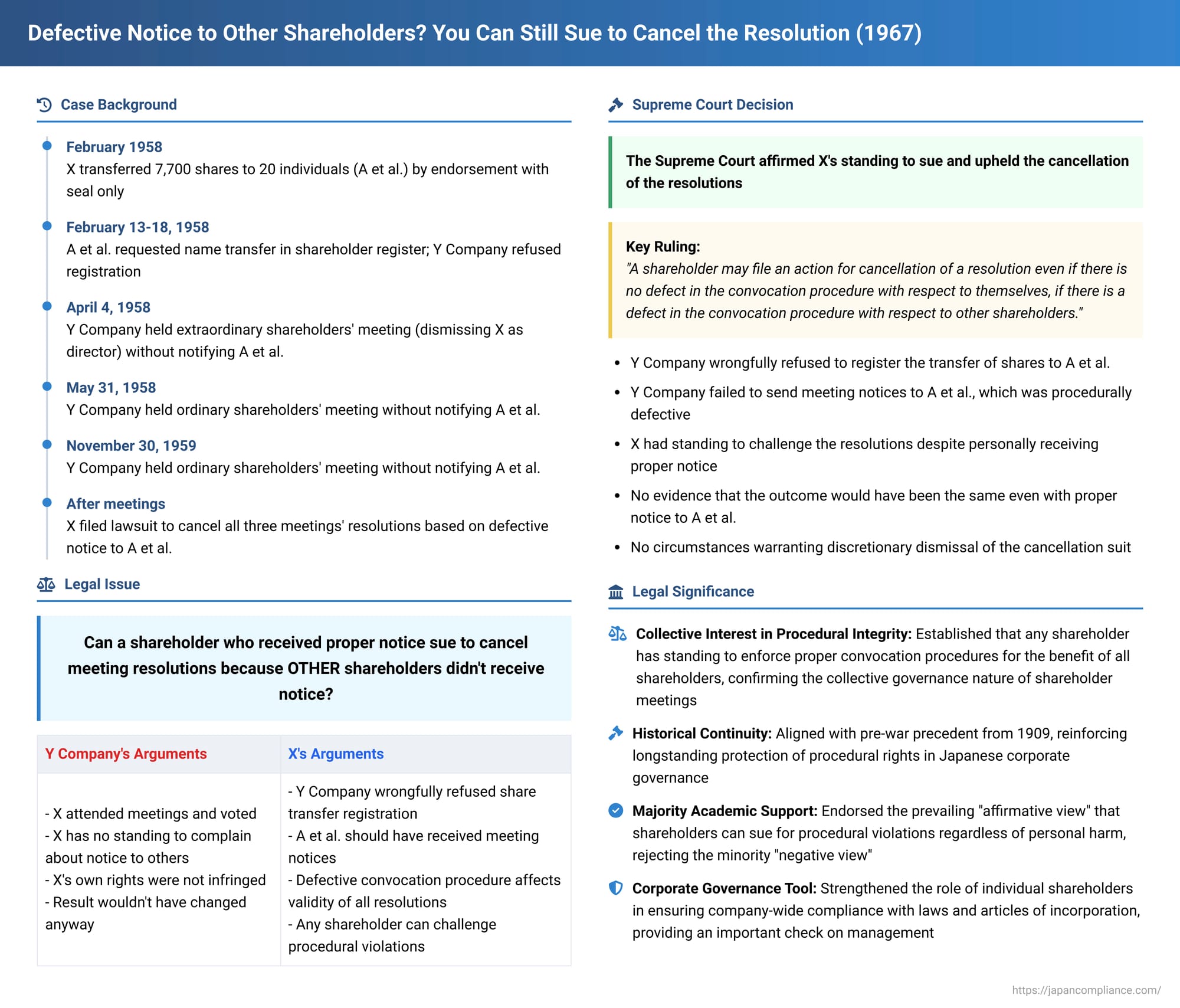

This 1967 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a significant question regarding shareholder rights: Can a shareholder, who themselves received proper notice for a shareholders' meeting, still bring a lawsuit to cancel resolutions passed at that meeting if the convocation procedures were flawed with respect to other shareholders? The Court unequivocally answered yes, emphasizing the collective interest in the lawful conduct of shareholder meetings.

Factual Background: A Disputed Share Transfer and Unnotified Meetings

The case involved X, a shareholder in Y Company, and a series of contentious shareholders' meetings.

- Challenged Resolutions: Y Company held three shareholders' meetings whose resolutions were challenged by X:

- An extraordinary meeting on April 4, 1958, which included a resolution to dismiss director X.

- An ordinary meeting on May 31, 1958, to approve financial statements and other matters.

- An ordinary meeting on November 30, 1959, also for approving financial statements.

- The Share Transfer and Refused Registration: On February 10, 1958, prior to these meetings, X had purportedly transferred 7,700 of their shares in Y Company (the "Shares in Question") to a group of 20 individuals, A et al. This transfer was done by endorsing the share certificates with only a seal imprint (natsu-in nomi no uragaki), a method whose validity was contested. Shortly thereafter, on February 13 and 18, 1958, A et al. presented these endorsed share certificates to Y Company and requested that the shares be transferred to their names on the company's shareholder register. Y Company took custody of the certificates but, according to the courts, refused the name transfer request without justifiable reason.

- Lack of Notice to New Shareholders: Subsequently, when Y Company convened the three shareholders' meetings mentioned above, it failed to send convocation notices to A et al., the purported new owners of the Shares in Question.

- X's Lawsuit: X filed a lawsuit to cancel the resolutions passed at these three meetings. X's argument was that because Y Company had wrongfully refused to register the transfer of the Shares in Question to A et al., Y Company could not deny the validity of that transfer. Consequently, Y Company was obligated to send convocation notices for the meetings to A et al. The failure to do so, X claimed, constituted a defect in the convocation procedure for each meeting, rendering the resolutions passed therein liable for cancellation.

- Y Company's Defenses: Y Company raised several defenses, including:

- Convocation notices only need to be sent to shareholders listed on the official shareholder register. Since A et al. were not registered, no notice was required for them.

- The share transfer itself (by endorsement with only a seal) was invalid, providing a justifiable reason for refusing the name transfer.

- X had attended the meetings and exercised voting rights for all their shares (including those purportedly transferred to A et al.) and therefore should be estopped from claiming procedural defects.

- Even if A et al. did not receive notice, their inability to vote would not have affected the outcome of the resolutions.

- (During the High Court appeal) Y Company added that a final Supreme Court judgment in a separate lawsuit between A et al. and Y Company had found Y Company's refusal of the name transfer to be justified, and the res judicata effect of this judgment should extend to X.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The Tokyo District Court (first instance) fully accepted X's claim and cancelled the resolutions.

- The Tokyo High Court (appellate instance) first determined that the res judicata effect of the separate Supreme Court judgment did not apply to X. It then found that, under the specific circumstances, Y Company had wrongfully refused the name transfer to A et al. Therefore, the failure to send convocation notices to A et al. rendered the convocation procedure for the meetings illegal. The High Court also found no merit in Y Company's other defenses and dismissed Y Company's appeal. Y Company then appealed to the Supreme Court. (The Supreme Court, in its judgment, noted that the underlying issue regarding the validity of share transfers by seal-only endorsement had since been resolved by a 1966 legislative amendment to the Commercial Code, which allowed registered shares to be transferred by mere delivery of the share certificate. Thus, the Supreme Court focused on the other aspects of the appeal).

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Shareholder Standing Affirmed

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal. In doing so, it affirmed the High Court's findings on the wrongfulness of refusing the name transfer and the inapplicability of res judicata. Crucially, regarding X's standing to sue based on defects affecting A et al., the Supreme Court stated:

"A shareholder may file an action for cancellation of a resolution even if there is no defect in the convocation procedure with respect to themselves, if there is a defect in the convocation procedure with respect to other shareholders. Therefore, X's filing of this action for cancellation of the resolutions on the grounds of defective convocation procedures with respect to shareholders A et al. is legitimate, and there is no illegality as alleged [by Y Company]."

The Court also noted that, based on the facts found by the High Court, there was no evidence to suggest that the inability of A et al. to exercise their voting rights (due to the lack of notice) did not influence the outcome of the resolutions. Furthermore, while acknowledging that a court has the discretion to dismiss a cancellation suit if, considering all circumstances, cancellation is deemed inappropriate (a principle now in Company Law Art. 831(2)), the Court found no such circumstances warranting discretionary dismissal in this particular case.

Analysis and Implications: Upholding Collective Shareholder Interests

This 1967 Supreme Court decision is a key affirmation of a shareholder's broad standing to challenge procedurally flawed resolutions, even if the flaw did not directly impact their own ability to participate.

1. The Central Question and the Court's Stance:

The core issue was whether a shareholder can sue to cancel a shareholders' meeting resolution based on defective convocation procedures that affected other shareholders. The Supreme Court's answer was a clear "yes." This stance was consistent with an old precedent from the Great Court of Cassation (Japan's highest court before World War II) dating back to March 25, 1909, which held that the failure to notify each shareholder of a meeting was a defect that any shareholder could use as a basis to seek the nullification of the meeting's resolutions. A later Supreme Court decision (September 9, 1997) also touched upon a similar theme, suggesting that failing to notify a particular shareholder of a meeting can constitute a breach of duty by the directors in relation to all shareholders, as it undermines the fair decision-making process of the shareholders' meeting, which is the company's ultimate decision-making body.

2. Historical Context of Shareholder Standing:

The evolution of Japanese company law reflects a broadening of shareholder standing in such matters. While an early 20th-century amendment to the Commercial Code had imposed some restrictions on which shareholders could sue for resolution cancellation (e.g., those who attended a meeting and did not object were barred), a 1938 amendment removed these limitations. This broader approach to standing was carried forward into the Commercial Code provisions applicable at the time of the 1967 judgment and is reflected in the current Company Law (Article 831(1)). The 1967 Supreme Court decision aligns with this post-1938 legislative stance favoring broader shareholder access to such remedies.

3. Academic Perspectives:

The question of standing in such scenarios has been debated among legal scholars:

- Affirmative View (Majority/Prevailing Theory): This view, which supports the Supreme Court's 1967 decision, is the dominant one in Japanese legal scholarship. The primary rationale is that a lawsuit to cancel a shareholders' meeting resolution is fundamentally aimed at ensuring the company operates in compliance with applicable laws and its own articles of incorporation. It serves as an important instrument of corporate governance, allowing shareholders to police the legality of corporate actions.

- Negative View: A minority of scholars argued that shareholders, unlike directors or corporate auditors (who have a duty to act in the interest of all shareholders), should only be able to challenge procedural defects that personally affect them. If a shareholder received proper notice and was able to participate, they should not, according to this view, have standing to sue based on a lack of notice to other shareholders.

4. Evaluation of the Supreme Court's Position:

While the negative view (that a shareholder should only sue for personal harm) has a certain logical appeal, the reasons for allowing resolutions to be cancelled due to convocation defects go beyond merely penalizing the procedural error itself. The underlying concern is that such defects might have prevented a fair and proper formation of the collective will of the shareholders.

The Company Law (Art. 831(1)) grants the right to sue for cancellation to "shareholders" in general, without imposing additional requirements such as proof of personal harm or having voiced an objection at the meeting. Given this statutory language and the fundamental nature of the resolution cancellation suit as a means to enforce lawful company operations and as a vital tool for shareholder-driven corporate governance, the Supreme Court's 1967 decision to allow shareholders to sue based on defects affecting others is widely considered appropriate and well-founded.

5. Related Considerations:

It's important to note a couple of related points:

- Curing of Defects: If the shareholders who were directly affected by the procedural defect (e.g., those who did not receive notice) subsequently take actions that indicate approval or waiver of the defect (for example, by attending the meeting and participating in the resolutions without raising an objection), the defect might be considered "cured," potentially precluding a cancellation suit based on that specific flaw.

- Waiver by Directly Affected Shareholder: However, even if a shareholder who was directly affected by a lack of notice decides to waive their personal right to sue for cancellation, the underlying procedural defect in the convocation process still technically exists. Such a personal waiver by one shareholder should not, therefore, affect the right of other shareholders to initiate a cancellation suit based on that same objective defect in the company's procedures.

Conclusion: Protecting the Integrity of Shareholder Meetings

The 1967 Supreme Court judgment robustly affirms that any shareholder has the standing to challenge a shareholders' meeting resolution if the convocation process was flawed with respect to any other shareholder, even if the suing shareholder personally received proper notice. This decision underscores the principle that all shareholders have a collective interest in ensuring that general meetings are conducted lawfully and that the resolution-making process is fair and transparent for everyone. By allowing such challenges, the Court reinforces the role of shareholders in upholding corporate governance standards and the overall integrity of company decision-making. The potential for discretionary dismissal by the court in cases where cancellation is deemed inappropriate serves as a check against purely vexatious litigation, but the fundamental right of shareholders to police procedural correctness remains intact.