Defamation Damages in Bankruptcy: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Exclusively Personal" Claims

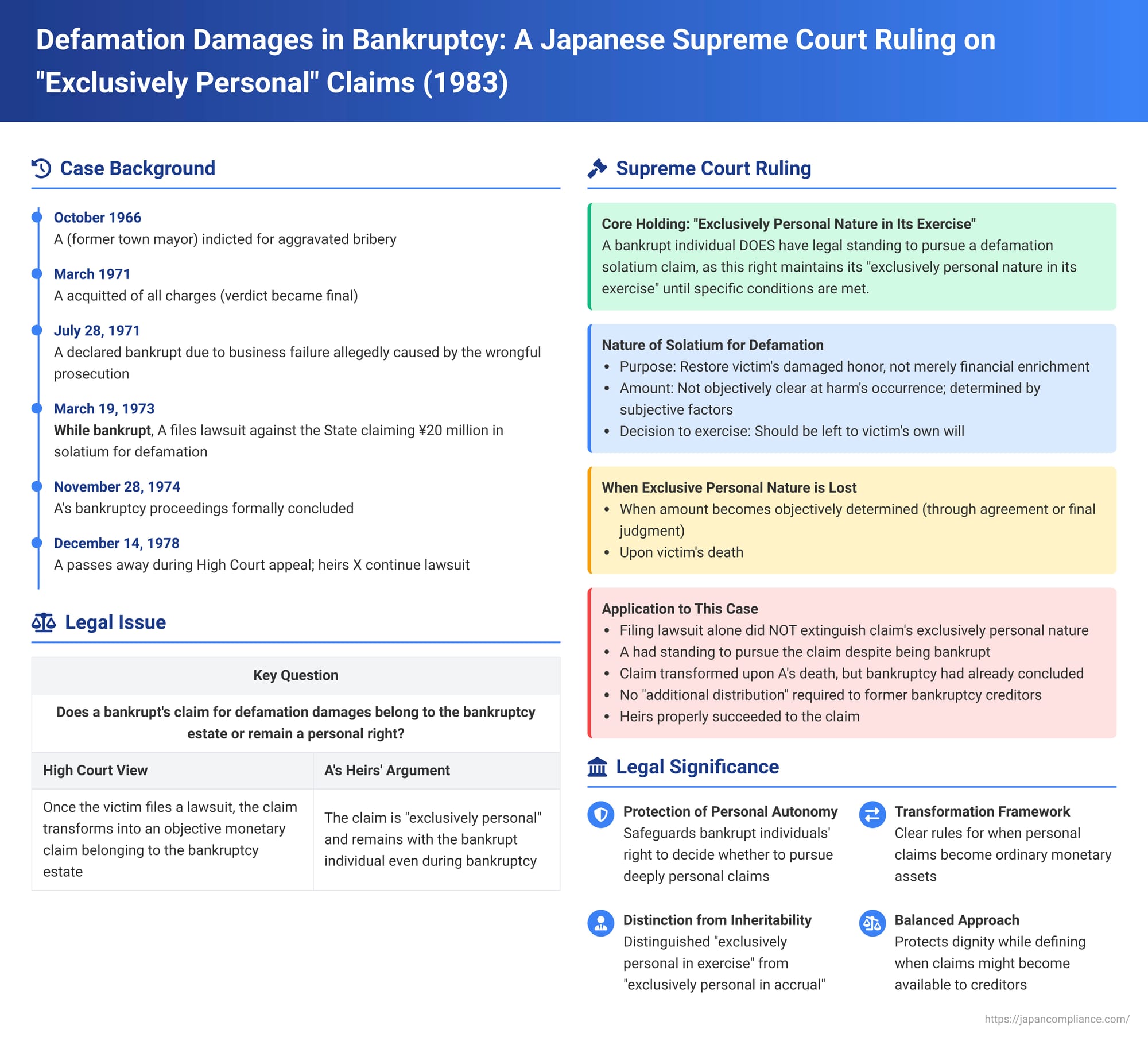

On October 6, 1983, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a key judgment concerning whether a bankrupt individual's claim for non-pecuniary damages (慰謝料 - isharyō, or solatium) arising from defamation belongs to the bankruptcy estate or remains a personal right of the bankrupt. The Court's decision hinged on the concept of the "exclusively personal nature in its exercise" of such claims, providing a nuanced framework for when these rights might become accessible to creditors.

Factual Background: Wrongful Prosecution, Bankruptcy, and a Claim for Solatium

The case originated with A, a former town mayor who was indicted in October 1966 for aggravated bribery. He was eventually acquitted in March 1971, and this acquittal became final. However, A contended that the wrongful prosecution had severely damaged his social reputation and caused his business to fail, leading to his declaration of bankruptcy on July 28, 1971, under Japan's old Bankruptcy Act.

While still undergoing bankruptcy proceedings, on March 19, 1973, A initiated a lawsuit against the State (Y). He claimed 20 million yen in solatium, alleging that his defamation resulted from the prosecutor's negligent and unlawful exercise of public authority in bringing the indictment. Subsequently, A's bankruptcy proceedings were formally concluded by a court order on November 28, 1974, while his defamation lawsuit against the State was still pending in the first instance court.

The Wakayama District Court (first instance) found that A had the legal standing to pursue the claim, affirmed the illegality of the prosecution, and ordered the State to pay A 2 million yen in solatium. The State appealed this decision. During the appeal proceedings at the Osaka High Court, A passed away on December 14, 1978. His heirs, X and others, took over (succeeded to) the lawsuit.

The Osaka High Court, however, took a different view on A's standing. It dismissed A's original lawsuit, reasoning that A, as a bankrupt, lacked the standing to bring it. The High Court opined that while a claim for solatium is personal, once the victim manifests an intent to exercise this right (e.g., by filing a lawsuit), it transforms into an objective monetary claim. If the victim is bankrupt at that point, such a claim would belong to the bankruptcy estate, and only the bankruptcy trustee would have the authority to manage and pursue it. Since A was bankrupt when he initiated the suit, the High Court concluded he lacked the necessary standing. A's heirs then appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Dilemma: Personal Rights vs. Bankruptcy Estate Assets

Under Japanese bankruptcy law, generally all property belonging to a bankrupt individual at the time bankruptcy proceedings commence forms the "bankruptcy estate" (破産財団 - hasan zaidan), which is then administered by a trustee for the benefit of creditors. However, an important exception exists for assets that are legally unattachable (差押禁止財産 - sashiosae kinshi zaisan). Rights that are "exclusively personal" to an individual (一身専属権 - isshin zenzokuken) are typically considered unattachable and thus do not become part of the bankruptcy estate.

The central legal question was whether a claim for solatium due to defamation qualifies as such an exclusively personal right, and if so, whether and when it might lose this characteristic and become an ordinary asset available to creditors.

The Supreme Court's Analysis of Solatium Claims

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision, finding that A did have standing to initiate the lawsuit.

- Nature of Solatium for Defamation: The Court began by analyzing the nature of a solatium claim for defamation. It acknowledged that it is a claim for monetary payment, similar to other monetary claims. However, its fundamental purpose is not the acquisition of financial wealth per se. Rather, it is a method to restore the victim's damaged personal value—their honor—by requiring the perpetrator to pay a sum of money that quantifies the mental distress suffered by the victim. Given this, the decision of whether or not to exercise such a right should, in principle, be left entirely to the victim's own will.

- Exclusively Personal Nature in Its Exercise (行使上の一身専属性 - kōshijō no isshin senzokusei): The Court emphasized that the specific monetary value of a solatium claim is not objectively clear at the moment the harm occurs. It is determined by a comprehensive assessment of various uncertain factors, including the degree of the victim's mental suffering, their subjective feelings and emotions, the attitude of the perpetrator, and other surrounding circumstances. Consequently, as long as a specific amount has not been objectively determined between the parties (for instance, through a settlement agreement or a final court judgment fixing the amount), it is appropriate to allow the victim to autonomously decide whether to continue pursuing the claim. During this phase, the right retains its "exclusively personal nature in its exercise." This means that the victim's creditors cannot attach the claim, nor can they exercise it on the victim's behalf through a creditor's subrogation action.

- Loss of Exclusively Personal Nature in Exercise: This exclusively personal nature in exercise is not permanent. The Court identified two situations in which it would be lost:

- When a specific monetary amount of solatium becomes objectively determined, either through an agreement between the victim and the perpetrator or by a final and binding court judgment ordering such payment. At this point, the claim becomes a straightforward monetary obligation awaiting fulfillment, and there is no special reason to leave its receipt solely to the victim's discretion.

- When the victim dies, even if the amount had not yet been objectively determined. Upon the victim's death, there is no longer a compelling reason to uphold the personal nature of its exercise for the successors to the claim.

In either of these scenarios, the solatium claim transforms into an objective monetary claim, detached from the victim's subjective will, and can then be subject to attachment by creditors or pursued via subrogation.

Application to the Bankrupt's Standing and the Bankruptcy Estate

Applying these principles to A's case:

- The mere fact that A, the original plaintiff, had manifested his intent to exercise his solatium claim by filing the lawsuit was not sufficient to extinguish the claim's exclusively personal nature in its exercise.

- Therefore, even though A was under bankruptcy proceedings at the time he initiated the lawsuit, this did not deprive him of the legal standing to do so. The High Court's decision to the contrary was erroneous.

- Impact of A's Death After Conclusion of His Bankruptcy: A passed away while the case was pending in the High Court. Upon his death, his solatium claim lost its exclusively personal nature in exercise. However, a critical fact was that A's personal bankruptcy proceedings had already been formally concluded in 1974, well before his death in 1978.

- The Supreme Court ruled that a solatium claim which loses its exclusively personal nature after the formal conclusion of the victim's bankruptcy proceedings is not subject to "additional distribution" (追加配当 - tsuika haitō) to the creditors of the former bankrupt under the provisions of the old Bankruptcy Act (Article 283, paragraph 1, latter part, now Article 215, paragraph 1 of the current Act).

- Consequently, A's solatium claim did not revert to his bankruptcy estate upon his death. Instead, the right to pursue the lawsuit was properly succeeded to by his heirs, X and others.

Significance and Implications

This 1983 Supreme Court judgment is highly significant for several reasons:

- It clearly established and defined the "exclusively personal nature in its exercise" for solatium claims arising from defamation. This provided crucial protection for a victim's autonomy in deciding whether to pursue such deeply personal claims, even if they are bankrupt.

- The decision distinguished this concept from the "exclusively personal nature in accrual" (帰属上の一身専属性 - kizokujō no isshin senzokusei). A prior 1967 Supreme Court decision had largely denied the latter for solatium claims in wrongful death cases, ruling them inheritable even if the victim had not manifested an intent to claim before death. The 1983 ruling clarified that even if a claim might be inheritable (not exclusively personal in accrual), its exercise could still be exclusively personal to the victim while alive and before the amount is fixed.

- The judgment provides a clear framework for determining when a solatium claim loses its personal character and becomes an ordinary monetary asset: upon objective determination of its amount or upon the victim's death. If this transformation occurs before or during bankruptcy proceedings (and prior to their conclusion), the claim could then potentially become part of the bankruptcy estate.

- The ruling on additional distributions is also noteworthy. By stating that a claim transforming into an ordinary asset after the bankruptcy proceedings have concluded does not become available for additional distribution to the former bankrupt's creditors, the Court, in such specific timing scenarios, effectively allows the victim's heirs to benefit rather than the creditors of the long-concluded bankruptcy.

- There remains some academic debate on whether solatium, given its purpose as compensation for purely personal suffering, should ever become part of a bankruptcy estate available to creditors, even if its amount becomes fixed.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1983 decision offers a carefully balanced approach to the treatment of solatium claims for defamation in the context of bankruptcy. It safeguards a bankrupt individual's autonomy and personal interest in deciding whether to pursue such claims, recognizing their intimate connection to personal dignity and mental suffering, at least until the claim is objectively monetized or the victim passes away. Simultaneously, it defines the conditions under which such a claim might transition into an ordinary asset. The ruling on the non-applicability of additional distribution for claims that transform post-bankruptcy conclusion further refines the boundaries between a concluded bankruptcy estate and the subsequent personal affairs of the former bankrupt or their heirs.