Defamation and Obstruction in Condominiums: When Do They Harm "Common Interests"? A 2012 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: January 17, 2012

Case Number: 2010 (Ju) No. 2187 (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench)

Introduction

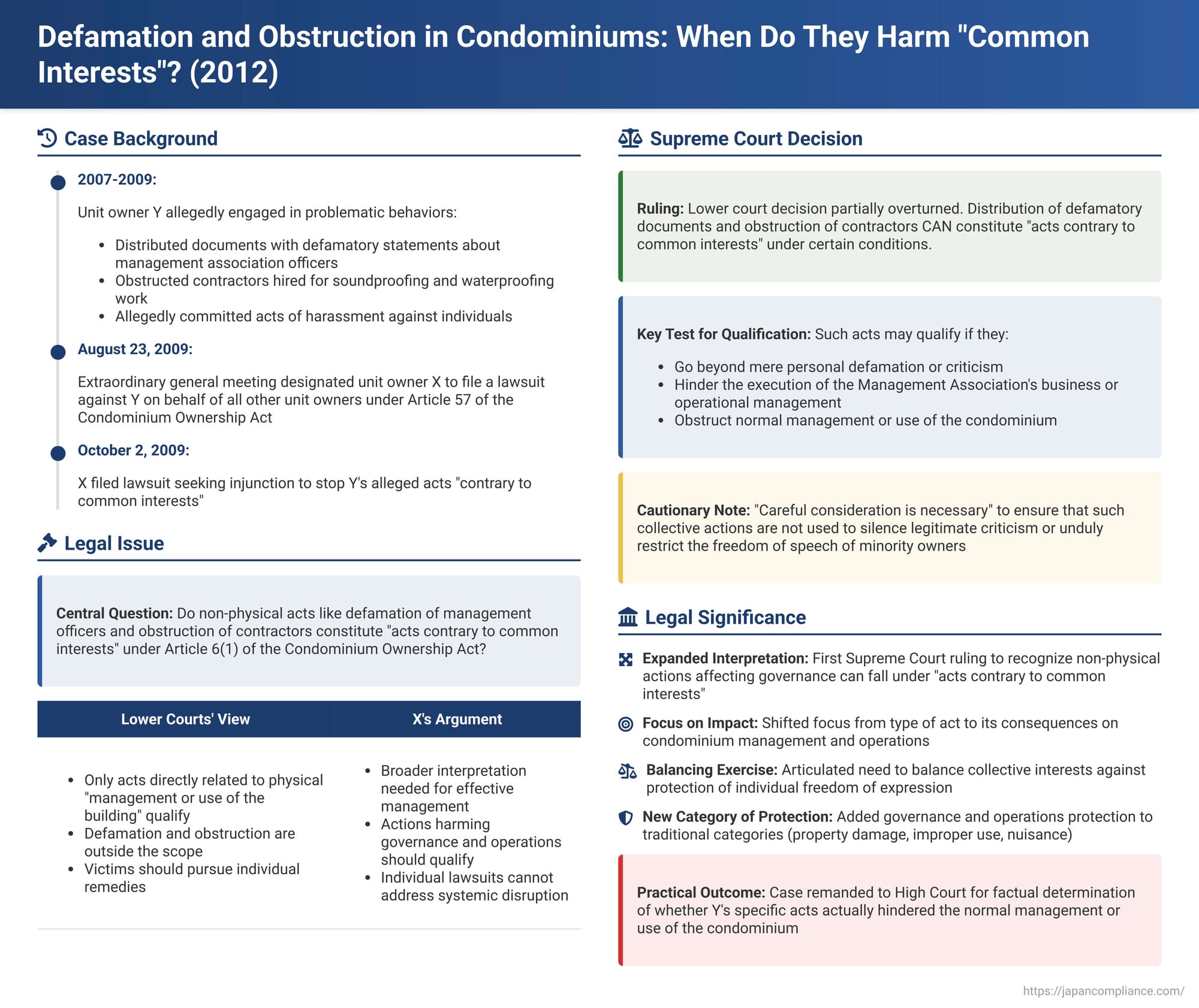

Life in a condominium community thrives on cooperation and adherence to rules designed to protect the collective well-being of all residents. However, disputes can arise, and occasionally, the actions of a single unit owner can disrupt the peace, hinder management, or create a hostile environment. Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA) provides mechanisms for addressing conduct by a unit owner that is "contrary to the common interests" of all owners. A key provision, Article 57, allows for legal action to stop such behavior.

A Supreme Court decision on January 17, 2012, significantly clarified the scope of what constitutes an "act contrary to the common interests of unit owners" under Article 6, Paragraph 1 of the COA. The case specifically examined whether actions like distributing defamatory documents about management association officers or obstructing contractors could fall under this category, even if they didn't involve direct physical misuse or damage to the condominium property.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved X and Y, both unit owners in "the Condominium."

Designation of X to File Suit:

On August 23, 2009, an extraordinary general meeting of the Condominium's unit owners passed a resolution. This resolution, made by all unit owners except Y, designated X to file a lawsuit against Y on behalf of all other unit owners. The purpose of the suit was to seek an injunction to stop certain actions by Y that were alleged to be "contrary to the common interests of unit owners" as defined in Article 6, Paragraph 1 of the COA. This collective action was authorized under Article 57, Paragraph 3 of the COA. X subsequently filed this lawsuit on October 2, 2009.

X's Allegations Against Y:

X alleged that Y, since around 2007, had repeatedly engaged in the following disruptive behaviors:

- Distribution of Defamatory Documents: Y allegedly distributed and posted documents containing defamatory statements about the elected officers of the Condominium's Management Association ("the Association"). These documents included accusations that the officers were misusing or arbitrarily managing the repair reserve funds. X claimed that Y engaged in these actions without first raising these concerns or expressing opinions through proper channels, such as at general meetings of the Association.

- Obstruction of Contractors' Business: Y was accused of actively obstructing contractors who had been legitimately hired by the Association to perform necessary soundproofing and waterproofing work on the Condominium. This alleged obstruction included sending the contractors unclear or harassing documents and making phone calls demanding that they cease their work or withdraw from their contracts.

- Assault and Harassment: X also alleged that Y had committed various acts of assault and harassment against individuals connected with the Condominium.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court (Yokohama District Court): The District Court dismissed X's claims.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court also dismissed X's appeal. Its reasoning was pivotal to the Supreme Court's later review. The High Court acknowledged that "acts contrary to the common interests of unit owners" under COA Article 6(1) typically include:However, the High Court found that the specific actions alleged against Y (distributing defamatory documents, obstructing contractors, alleged harassment) were not acts directly related to the physical "management or use of the building itself." It distinguished Y's alleged conduct from traditional nuisance issues like noise or smells. Therefore, the High Court concluded that these actions did not fall within the scope of COA Article 6(1). It suggested that individuals who were directly harmed by Y's specific actions (e.g., the defamed officers, the obstructed contractors, or harassed individuals) should pursue their own individual legal remedies, such as personal lawsuits for defamation, business interference, or damages for assault, rather than X seeking a collective injunction under COA Article 57.

- Improper damage to the building (e.g., unauthorized alterations to common elements).

- Improper use of the building (e.g., using a residential unit for a prohibited commercial purpose).

- Nuisance-type activities (e.g., excessive noise, vibrations, emission of foul odors, or other actions that are detrimental to other residents' property or health, or cause significant annoyance).

Dissatisfied with this narrow interpretation, X appealed to the Supreme Court. X argued that "acts contrary to common interests" should be interpreted more broadly to include any conduct that causes disadvantage to the lives of condominium residents, whether physically or psychologically, and asserted that individual lawsuits by various affected parties would not lead to a fundamental or comprehensive resolution of the ongoing disruption caused by Y.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of January 17, 2012, partially overturned the High Court's ruling. It found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of COA Article 6, Paragraph 1, and remanded the case for further proceedings concerning the injunction sought under COA Article 57. (The appeal on other grounds was dismissed).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. A Note of Caution: Protecting Freedom of Expression:

The Court began with an important cautionary note. It stated that when considering a request for an injunction under COA Article 57 (which allows the collective body of unit owners to sue an individual owner), "careful consideration is necessary" to ensure that the requirements for such an injunction are met. This is particularly true to avoid such legal actions being used to "silence, in the name of the majority, the speech and conduct of those pointing out alleged improprieties within the condominium" or to "unduly restrict the freedom of speech of minority owners." A balance must be struck.

2. Broadening the Interpretation of "Acts Contrary to Common Interests" (COA Article 6, Paragraph 1):

Despite this initial caution, the Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's narrow interpretation of COA Article 6(1).

- It held that actions by a condominium unit owner, such as distributing documents that defame the officers of the Management Association who are engaged in their duties, or obstructing the business of contractors hired for condominium works (like soundproofing), can potentially fall within the scope of "acts contrary to the common interests of unit owners" as defined in COA Article 6, Paragraph 1.

- The Key Condition for Qualification: For such acts to qualify, they must:

- Go beyond the realm of mere personal defamation or criticism directed at specific individuals.

- And, as a result of these actions, **hinder the execution of the Management Association's business or its operational management, or otherwise obstruct the normal management or use of the condominium. **

3. The High Court's Error in Legal Interpretation:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of COA Article 6, Paragraph 1.

- The High Court had too narrowly focused on whether Y's alleged acts directly involved the physical aspects of "management or use of the building" (like noise or physical damage).

- X, in the lawsuit, had specifically argued that Y's conduct was not merely a series of personal attacks but was actively causing disruptions to the Management Association's ability to carry out its duties and was impeding the smooth progress of legitimately approved condominium works (such as soundproofing projects).

- The High Court failed to properly deliberate on the factual questions of whether Y had actually engaged in the alleged conduct and, crucially, whether these actions had, in fact, resulted in the obstruction of the Condominium's "normal management or use." Dismissing X's claim based solely on the nature of Y's alleged acts, without fully examining their impact on the collective interests of the condominium community, was an error of law.

4. Remand for Further Deliberation:

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's judgment concerning the claim for an injunction under COA Article 57 must be overturned.

- The case was remanded back to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court was instructed to conduct a thorough examination of the facts to determine:

- Whether Y had indeed engaged in the alleged conduct (distribution of defamatory documents, obstruction of contractors, etc.).

- If so, whether this conduct, by its nature and consequences, hindered the normal management or use of the Condominium to such an extent that it constituted an "act contrary to the common interests of unit owners" under COA Article 6(1).

Only after these factual determinations could a proper judgment be made on whether X's request for an injunction under COA Article 57 was justified.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2012 decision is significant for expanding the understanding and application of what constitutes an "act contrary to the common interests of unit owners" in Japanese condominium law.

1. Significance of Broadening COA Article 6(1):

This was a landmark ruling as it was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly recognized that non-physical actions—such as the systematic defamation of management association officers or the deliberate obstruction of legitimate association business (like contracts for building maintenance)—could indeed fall under the COA Article 6(1) definition. This interpretation moves beyond a purely property-centric or traditional nuisance-based understanding of "common interests." It acknowledges that the smooth functioning and governance of the management association are themselves vital common interests of all unit owners.

2. Focus on Impact, Not Just the Type of Act:

The critical factor highlighted by the Supreme Court is the consequence or impact of the disruptive behavior on the collective. It's not merely the type of act (e.g., distributing flyers versus making excessive noise) that determines whether it's contrary to common interests, but whether that act genuinely obstructs or impairs the "normal management or use of the condominium."

3. What Constitutes "Obstruction of Normal Management or Use"?

While the Supreme Court did not provide an exhaustive list, legal commentary following the decision suggests that such obstruction could include a variety of scenarios, such as:

- Actions that make it difficult to find or retain individuals willing to serve as unpaid officers of the management association due to a hostile or defamatory environment.

- Conduct that delays, prevents, or makes more costly the conclusion or performance of necessary contracts with third-party vendors for building maintenance, repairs, or improvements.

- Behavior that generally disrupts the peaceful living environment or the orderly and effective administration of the condominium by the management association.

4. Balancing Collective Interests with Freedom of Expression:

The Supreme Court's initial cautionary note about protecting the freedom of speech of unit owners, especially those in a minority or those raising potentially legitimate concerns about management, is profoundly important. The ruling does not mean that any criticism of the management association or its officers will automatically be deemed an "act contrary to common interests." A high bar is set: the conduct must go beyond reasonable criticism or expressions of discontent and must genuinely impede the association's essential functions or the normal use of the condominium to a significant degree. This requires a careful, fact-sensitive balancing act by the courts.

5. Relationship with Individual Legal Remedies:

The High Court had suggested that individual victims of Y's alleged actions should pursue their own separate lawsuits. The Supreme Court, by allowing the COA Article 57 claim (a collective action) to potentially proceed, implicitly acknowledged that some disruptive behaviors have a broader, collective dimension of harm that may not be adequately or efficiently addressed by a series of individual lawsuits. An Article 57 action, initiated by a resolution of the general meeting (or by the management association itself if it has legal personality and appropriate authorization), aims to protect the common interest of all (or all other) unit owners in the proper management and peaceful use of their shared living environment. This collective remedy can exist alongside, and does not necessarily preclude, individual legal actions by those who have suffered specific personal harm (e.g., a defamed officer suing for personal damages).

6. Expanding the Categories of Prohibited Conduct:

Historically, "acts contrary to common interests" under COA Article 6(1) were often categorized by legal scholars and in court precedents into:

- Improper physical damage to the building (e.g., unauthorized structural alterations, damage to common elements).

- Improper use of the building or private units (e.g., using a residential unit for a prohibited commercial purpose, unauthorized construction on balconies or other common areas).

- Nuisance or infringement of privacy (e.g., persistent excessive noise, creation of unsanitary conditions like feeding pigeons that cause widespread mess, keeping prohibited animals that disturb neighbors).

This Supreme Court ruling effectively adds a new dimension, clarifying that conduct primarily targeting the governance, operations, and legitimate business activities of the management association can also fall under this provision if the negative impact on the collective is sufficiently severe.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2012 decision significantly broadened the interpretation of "acts contrary to the common interests of unit owners" within the framework of Japan's Condominium Ownership Act. It established that disruptive conduct, including non-physical actions like the systematic defamation of management association officers or the deliberate obstruction of essential contractors, can be subject to collective injunctive relief if such actions go beyond personal grievances and demonstrably hinder the normal management, operation, or use of the condominium. However, this expanded scope is carefully counterbalanced by the imperative to protect the legitimate freedom of expression of unit owners. Courts are tasked with a nuanced, fact-based assessment to ensure that collective legal actions are used to address genuine harm to the community's common interests, rather than to suppress dissent or reasonable criticism within the condominium. This ruling provides an important tool for condominium communities to address serious internal disruptions while reminding them of the need for careful judgment in its application.