Deducting Future Costs: Japanese Supreme Court on 'Cost of Sales' and Unfixed Liabilities

Date of Judgment: October 29, 2004

Case Name: Corporate Tax Act Violation Case (平成12年(あ)第1714号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

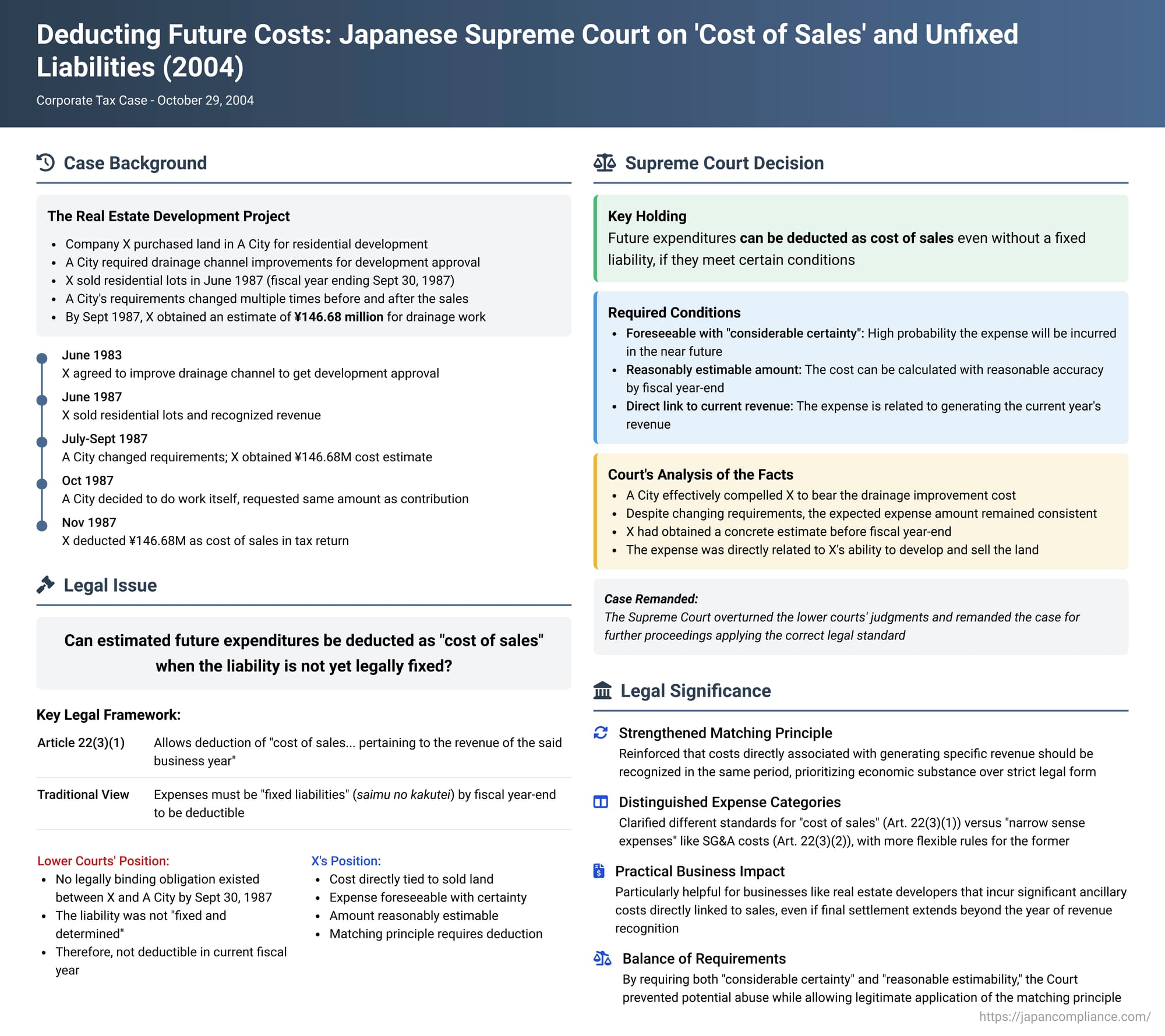

In a significant judgment on October 29, 2004, the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial clarification on the deductibility of estimated future expenditures as "cost of sales" under Article 22, paragraph 3, item 1 of the Corporate Tax Act. The ruling addressed whether a company could deduct such costs in the fiscal year revenue was recognized, even if the legal liability for these future expenditures was not yet definitively "fixed and determined" by the end of that year. This case, though arising from a criminal tax evasion prosecution, has important implications for how cost of sales is interpreted in civil tax matters as well, particularly concerning the matching of expenses with revenues.

The Developer's Dilemma: Shifting Demands and Uncertain Costs

The case involved a real estate development company, X, and its representative director. X had purchased land in a municipality, A City (then a town), with the intention of developing it into residential lots for sale.

The development project encountered several complexities related to local administrative guidance:

- Initial Condition for Approval: To obtain the necessary development approval from the prefectural governor, X needed the consent of A City, as stipulated by the Urban Planning Act (Article 32). A City leveraged this consent power to instruct X to undertake specific infrastructure improvements. This included the整備 (seibi - development/improvement) of a rainwater drainage channel located outside X's development area, approximately 400 meters long and involving the burial of a 2-meter diameter pipe (referred to as "Plan 1"). X agreed to these conditions and received the development approval in June 1983.

- Land Sales and Revenue Recognition: X proceeded with the land development and successfully sold the residential lots in June 1987. The revenue from these sales was recorded in its books for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1987 (referred to as "the current term").

- A City's Shifting Demands: Subsequent to the land sales, A City's guidance regarding the drainage channel underwent several changes:

- Around July 1987, A City officials altered their instructions, now requiring a 4-meter wide open channel instead of the piped one. This new design was estimated to cost approximately three times more than Plan 1. When X expressed reluctance due to the increased cost, A City officials proposed a compromise: X could partially construct the 4-meter open channel, but the expenditure would be kept within the original cost estimate for Plan 1. X accepted this and requested a construction company to prepare an estimate based on the original Plan 1 scope.

- Around September 1987 (still within "the current term"), the construction company provided an estimate of ¥146.68 million for the work under Plan 1's scope, and X communicated this figure to A City officials.

- Around October 1987 (just after "the current term" ended), A City changed its policy again. It decided that the municipality itself would undertake the improvement work as a public project. In turn, A City requested X to pay the previously estimated amount of ¥146.68 million (the Plan 1 cost) to A City as a "contribution for urban drainage channel improvement" (都市下水路整備負担金 - toshi gesuiro seibi futankin). X agreed to this arrangement.

- Tax Filing and Subsequent Non-Payment: In its corporate tax return for "the current term" (fiscal year ending September 30, 1987), filed on November 30, 1987, X deducted the ¥146.68 million as part of its cost of sales related to the land sold during that year.

- In reality, A City, while budgeting for a portion of this contribution from X in its fiscal 1988 budget (passed in March 1988) for a planned three-year construction project, never actually carried out the work due to concerns about potential resident opposition. Consequently, X also never paid the ¥146.68 million contribution.

This deduction led to X and its representative director being prosecuted for filing a false tax return and evading corporate income tax for "the current term". The lower courts (Mito District Court and Tokyo High Court) found them guilty, ruling that the ¥146.68 million could not be deducted as cost of sales in "the current term". The District Court reasoned that no legally binding rights or obligations concerning the work had been established between X and A City by year-end. The High Court held that for the contribution to be deductible as cost of sales, its payment must have been a "fixed and determined liability" (saimu toshite kakutei shiteita), meaning the content of the obligation was objectively and unequivocally clear, and the expense specific enough to be estimated, which it found was not the case.

The Legal Battleground: "Cost of Sales" vs. "Fixed Liability"

The central legal question that reached the Supreme Court was whether an estimated future expenditure, which is closely linked to revenue recognized in a particular fiscal year, can be deducted as "cost of sales" under Corporate Tax Act Article 22, paragraph 3, item 1 in that same year, even if the legal liability for that expenditure has not become "fixed and determined" by the end of the fiscal year.

Article 22, paragraph 3, item 1 of the Corporate Tax Act allows for the deduction of "the amount of cost of sales... pertaining to the revenue of the said business year". However, Japanese tax law often emphasizes the principle of "fixation of liability" (saimu no kakutei) for the deductibility of many types of expenses, particularly those falling under Article 22, paragraph 3, item 2 (often termed "narrow sense expenses" like selling, general, and administrative expenses). According to tax circulars (e.g., Corporate Tax Basic Circular 2-2-12), a liability is generally considered "fixed" if, by the end of the fiscal year: (i) the debt itself has been legally established; (ii) the event causing the specific payment obligation under that debt has occurred; and (iii) the amount of the obligation can be reasonably calculated.

The appellants' case hinged on whether this strict "fixation of liability" standard also applied to items claimed as "cost of sales," or if the direct link to realized revenue allowed for the deduction of a reasonably estimated, highly probable future cost.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification

The Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the lower courts and remanded the case, effectively ruling in favor of the principle that the ¥146.68 million could be deductible as cost of sales in "the current term," provided certain conditions regarding foreseeability and estimability were met, even without a legally "fixed and determined" liability by the year-end.

The Court's reasoning was based on a careful review of the factual circumstances:

- Effective Compulsion: A City had used its consent power under the Urban Planning Act as leverage to require X to undertake the improvement work (or bear its cost). This placed X in a position where it effectively had no choice but to incur the expense to proceed with its development project and sell the land.

- Consistent Cost Expectation: Despite the changes in A City's specific demands regarding the nature of the work, the amount of expenditure X was expected to bear remained consistently tied to the initial estimate for Plan 1 (¥146.68 million).

- Anticipation and Quantification by Year-End: X had already anticipated this expenditure and had taken concrete steps to quantify it by obtaining the construction estimate from a third party around September 1987, which was before the close of "the current term" (September 30, 1987).

Based on these points, the Supreme Court concluded that as of September 30, 1987 (the end of "the current term"):

- It was foreseeable with a "considerable degree of certainty" (sōtō teido no kakujitsusei) that X would have to incur this expense in the near future.

- The amount of this expense could be "reasonably estimated" (tekisei ni mitsumoru koto ga kanō de atta) based on the circumstances prevailing on that date.

The Key Holding: The Supreme Court ruled that when such circumstances exist—that is, when a future expenditure is foreseeable with considerable certainty and its amount is reasonably estimable by year-end—it is appropriate to deduct that estimated amount as "cost of sales pertaining to the revenue of the said business year" under Corporate Tax Act Article 22, paragraph 3, item 1, even if the liability for that specific expense has not become legally "fixed and determined" by the end of that fiscal year. The lower courts had therefore erred in their interpretation of the law regarding deductible cost of sales.

Understanding the Nuance: Cost of Sales vs. Other Expenses

Legal commentary on this decision emphasizes the distinction between different categories of deductible items under the Corporate Tax Act and how the "fixation of liability" principle applies:

- Cost of Sales (Article 22(3)(1)): The primary driver for recognizing cost of sales is the matching principle—costs directly associated with generating specific revenue should be recognized in the same period as that revenue. The Supreme Court's ruling affirms that for this category, if a future cost is inextricably linked to current sales (as the drainage contribution was effectively linked to X's ability to sell the developed lots), it can be accrued and deducted based on reasonable estimation and high probability, even if not yet a fixed legal debt. This is consistent with certain established accounting practices, such as the use of estimated standard costs in manufacturing, which are also accepted for tax purposes in Japan (Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order Art. 32(2)). Tax circulars had, in fact, moved away from a strict liability fixation requirement for cost of sales since a 1980 amendment (former Corporate Tax Basic Circular 2-1-4 was rescinded, and Circular 2-2-1 allowing for estimation was introduced).

- "Narrow Sense" Expenses (Article 22(3)(2)): For expenses like selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs, which often relate to a period rather than specific items of revenue, the "fixation of liability" rule (requiring debt establishment, a causal event for payment, and reasonable calculability of the amount by year-end) generally serves as a more stringent gatekeeper. This is to prevent premature or arbitrary deductions for costs that do not have a direct, individual correspondence with recognized revenue.

- Losses (Article 22(3)(3)): This category, which can include things like damage to assets from disasters, often does not involve a "liability" to a third party in the first place, so the concept of liability fixation is largely irrelevant.

Commentators suggest that the Supreme Court's emphasis on "considerable certainty" and "reasonable estimability" was particularly pertinent in this case due to the somewhat ambiguous nature of the ¥146.68 million expenditure. Given the shifting demands from A City and the fact it was ultimately framed as a "contribution" that was never paid, its character as a true "cost of sales" (directly and exclusively tied to the land sold) versus a more general business expense, a levy, or even a donation to a local government (which would fall under different deduction rules potentially requiring liability fixation) was debatable. Had the expenditure been more clearly argued as lacking a direct correspondence with the specific land sales revenue, the outcome might have differed.

Implications of the Ruling

This Supreme Court judgment has several important implications:

- It strongly reinforces the matching principle in the context of cost of sales, prioritizing the economic link between revenue and the costs incurred to generate that revenue.

- It provides clear judicial backing for the deduction of reasonably certain and estimable future costs as cost of sales when they are directly tied to current-year revenue, even if those liabilities are not yet legally "fixed and determined" in a strict sense. This moves beyond a rigid, universal application of the "fixation of liability" doctrine for this particular category of expense.

- While this specific case was a criminal tax matter involving allegations of tax evasion, the Supreme Court's interpretation of what constitutes a deductible "cost of sales" under the Corporate Tax Act is equally relevant and authoritative for civil tax disputes and general tax planning.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision offers a nuanced but clear pathway for deducting certain future costs as cost of sales. By focusing on the "considerable certainty" of the future expenditure and the "reasonable estimability" of its amount by the fiscal year-end, the Court prioritized the economic substance of matching costs with revenues over a strict, universally applied "fixation of liability" requirement for this specific category of deductions. This ruling is particularly important for businesses, like real estate developers, that may incur significant ancillary costs directly linked to sales, even if the final settlement of those costs extends beyond the year of revenue recognition. It underscores that when future obligations are effectively imposed as a condition of earning current revenue and can be reliably quantified, they can be appropriately accrued as part of the cost of generating that revenue.