Dividend Withholding in Japan: Do You Meet the 6-Month Treaty Holding-Period Rule?

TL;DR

- Japan’s bilateral tax treaties can slash dividend withholding tax, but parent companies must often meet strict share-holding-period tests.

- A 2022 Tokyo District Court case on the Japan–Luxembourg treaty shows how Japanese courts calculate the six-month period—looking to the end of the subsidiary’s fiscal year, not the dividend entitlement date.

- U.S. multinationals should audit treaty language, deemed-dividend events, and NTA guidance to secure reduced rates.

Table of Contents

- Withholding Tax on Dividends and the Role of Tax Treaties

- Preventing Treaty Abuse: Understanding Holding Period Requirements

- Interpreting Tax Treaties: International Principles and Japanese Practice

- The Tokyo District Court Case (Feb 17 2022): A Holding Period Dispute

- Significance of the Court's Methodology

- Implications for U.S. Businesses

- Conclusion

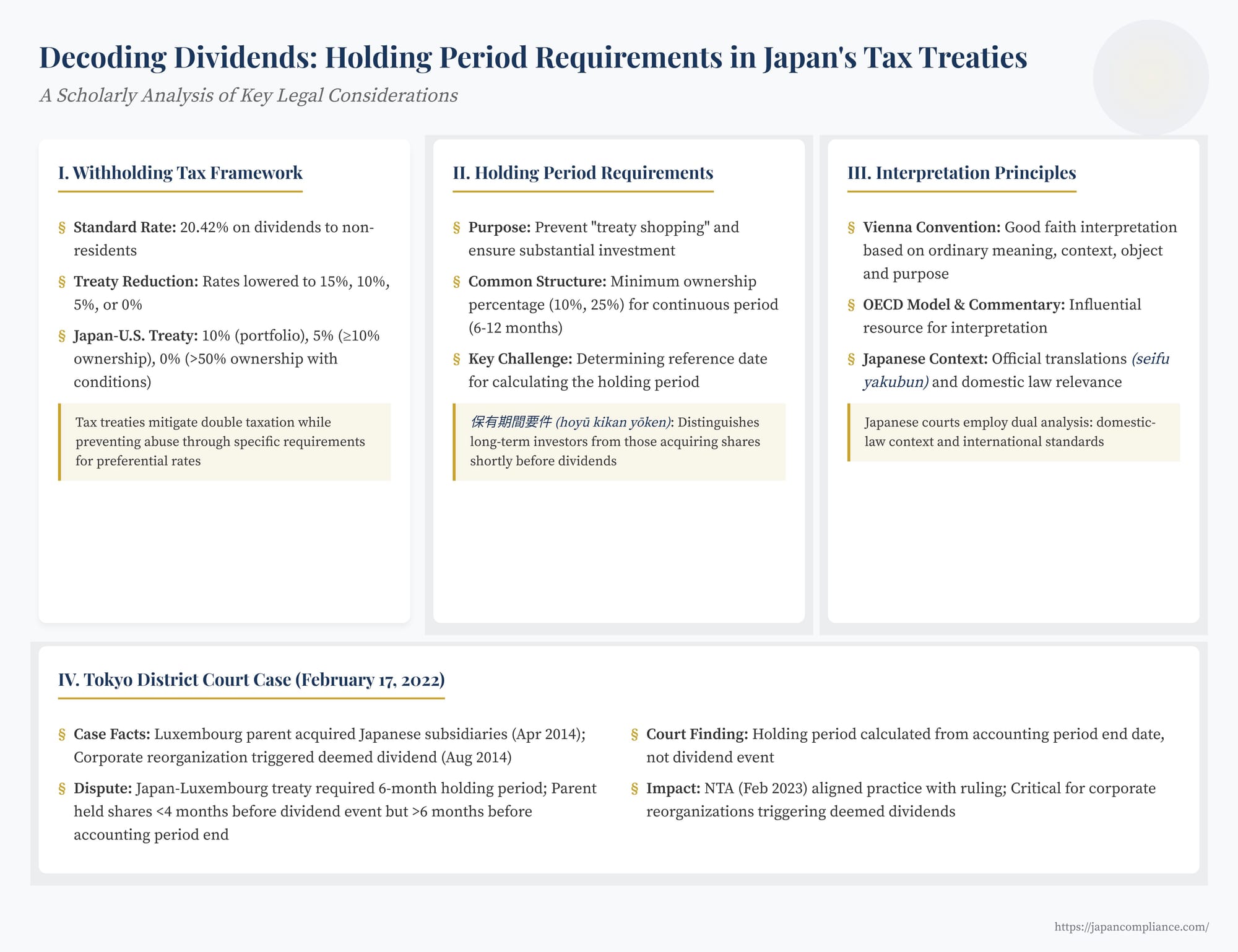

For U.S. corporations with Japanese subsidiaries, receiving dividends is a common way to repatriate profits. However, these cross-border payments are typically subject to Japanese withholding tax. Bilateral tax treaties between Japan and other countries, including the United States, often play a crucial role in mitigating this tax burden by providing for reduced withholding tax rates. Yet, accessing these preferential rates isn't automatic; treaties frequently contain specific conditions designed to prevent abuse, such as minimum holding period requirements for the parent company's shares in the subsidiary.

The precise interpretation of these requirements can sometimes become a point of contention, involving complex interactions between international treaty language, domestic law, and established principles of treaty interpretation. A Tokyo District Court judgment on February 17, 2022 (Reiwa 4), involving the Japan-Luxembourg tax treaty, provides a significant case study on how Japanese courts approach the interpretation of such holding period clauses, offering valuable insights for multinational businesses navigating dividend payments from Japan.

Withholding Tax on Dividends and the Role of Tax Treaties

Under Japan's domestic tax law, dividends paid by a Japanese company to a non-resident shareholder (like a U.S. parent company) are generally subject to a withholding tax. The standard rate is currently 20.42% (comprising 20% national income tax and 0.42% special reconstruction income tax).

However, Japan has an extensive network of bilateral tax treaties designed to prevent double taxation and fiscal evasion. A key function of these treaties is often to reduce the withholding tax rate imposed by the source country (Japan, in this case) on dividends paid to residents of the treaty partner country. Depending on the specific treaty and the circumstances, the rate on dividends can be reduced to 15%, 10%, 5%, or even 0% (full exemption). For example, the current Japan-U.S. tax treaty generally provides for a 10% rate on portfolio dividends and a 5% rate for dividends paid to a parent company holding at least 10% of the voting stock, with a potential 0% rate if the parent holds more than 50% of the voting stock for at least 12 months and meets other stringent conditions.

Preventing Treaty Abuse: Understanding Holding Period Requirements

These reduced treaty rates are intended to benefit genuine investors with substantial economic ties between the two countries. To prevent "treaty shopping" – where investors structure arrangements primarily to gain access to favorable treaty rates without a significant underlying economic connection or investment duration – modern tax treaties often include specific anti-abuse provisions.

One common type of anti-abuse rule, particularly relevant for accessing the lowest "parent-subsidiary" dividend rates (e.g., 5% or 0%), is the holding period requirement (保有期間要件 - hoyū kikan yōken).

- Purpose: The fundamental goal of a holding period requirement is to ensure that the parent company receiving the reduced tax rate has maintained a significant and relatively stable investment in the subsidiary for a specified duration before becoming entitled to the dividend. This helps distinguish long-term investors from those who might acquire shares shortly before a dividend payment solely to exploit the lower treaty rate and then quickly dispose of them.

- Common Structure: Typically, these clauses require the recipient company (the parent) to have held a certain minimum percentage of the paying company's (the subsidiary's) capital or voting power (e.g., 10%, 25% or more) for a continuous minimum period (e.g., 6 months, 12 months) ending on or spanning the date the entitlement to the dividend is determined.

The precise wording and the specific duration vary from treaty to treaty, making careful examination of the applicable convention essential.

Interpreting Tax Treaties: International Principles and Japanese Practice

Tax treaties are international agreements, and their interpretation is governed by principles of international law, primarily codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

- Vienna Convention Article 31: This key article mandates that a treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.

- OECD Model and Commentary: The OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and its accompanying Commentary are highly influential resources used globally as aids to treaty interpretation. While not legally binding in themselves, the OECD Commentary provides crucial context and explanations regarding the intended meaning and purpose of provisions commonly found in treaties based on the Model. Japanese courts, including the Supreme Court, have previously acknowledged the importance of the OECD Commentary as a supplementary means of interpretation (as per Vienna Convention Article 32) or as relevant context shedding light on the ordinary meaning and purpose under Article 31.

- Language and Domestic Law: A practical challenge arises when the authentic text(s) of a treaty are in languages other than Japanese (often English and/or French), yet the treaty must be applied within Japan. Japanese tax authorities and courts often refer to the official Japanese translation (seifu yakubun) prepared by the government during the ratification process. Furthermore, many treaties contain a clause similar to Article 3(2) of the OECD Model, stating that any term not defined in the treaty shall, unless the context otherwise requires, have the meaning it has under the domestic law of the state applying the treaty concerning the taxes to which the treaty applies. This necessitates considering the interplay between international treaty terms and their potential counterparts or interpretations within Japanese tax law.

The Tokyo District Court Case (Feb 17, 2022): A Holding Period Dispute

The February 17, 2022, Tokyo District Court decision provides a concrete example of these interpretive principles in action, specifically concerning a holding period requirement in the Japan-Luxembourg Tax Treaty.

- The Factual Scenario:

- A Luxembourg-resident parent company acquired 100% of the shares of two Japanese subsidiaries on April 29, 2014.

- On August 1, 2014, the Japanese subsidiaries underwent a corporate reorganization (a spin-off, 分割型分割 - bunkatsu-gata bunkatsu). This reorganization triggered a "deemed dividend" (minashi haitō) under Japanese tax law, which was treated as a dividend payment from the subsidiaries to the Luxembourg parent.

- Japan withheld tax on this deemed dividend at the standard domestic rate.

- The Luxembourg parent sought a refund, arguing that the lower 5% rate under the Japan-Luxembourg treaty should apply.

- The Treaty Provision and Dispute:

- Article 10(2)(a) of the Japan-Luxembourg treaty stipulated a 5% withholding tax rate for dividends if the beneficial owner was a company holding at least 25% of the paying company's voting power "throughout the period of six months ending on the date on which entitlement to the dividends is determined" (this is the typical OECD phrasing, though the court focused on the specific wording related to the accounting period).

- The parent company clearly met the 25% ownership threshold. The dispute centered on the six-month holding period.

- The parent had held the shares for less than six months before the deemed dividend event occurred (August 1, 2014).

- However, the parent had held the shares for more than six months before the end of the Japanese subsidiaries' accounting period during which the dividend distribution took place (October 31, 2014).

- The critical interpretive question was: What is the reference date for calculating the six-month holding period backwards? The treaty text (specifically, the official Japanese translation thereof: 「利得の分配に係る事業年度の終了の日」 - ritoku no bunpai ni kakaru jigyō nendo no shūryō no hi) referred to "the end of the accounting period for which the distribution of profits takes place."

- The Japanese tax authority argued this phrase should effectively mean the date the dividend entitlement itself was determined (the date of the spin-off).

- The taxpayer argued it should be interpreted literally as the end date of the subsidiary's accounting period during which the distribution occurred.

- The Court's Interpretive Approach and Decision:

The Tokyo District Court sided with the taxpayer, finding that the 5% reduced rate applied. The court's methodology was notable:- No Definition in Treaty: It first confirmed that the treaty itself did not define the specific phrase in question.

- Context - Domestic Law via Official Translation: It then invoked Article 3(2) of the treaty (directing reference to domestic law for undefined terms) and looked at the official Japanese government translation (seifu yakubun) of the treaty text to understand the term's meaning within the Japanese legal context. Based on this, it concluded the phrase meant "the end date of the accounting period related to the distribution of profits."

- Object and Purpose / Ordinary Meaning: The court did not stop there. It also explicitly applied the general rule of interpretation from Vienna Convention Article 31, examining the "ordinary meaning" of the terms (based on the authentic English text) in light of the treaty's "object and purpose." In doing so, it considered the purpose of holding period requirements generally (to prevent short-term share acquisitions for tax avoidance) and referred to the OECD Model Convention and its Commentary as key interpretive aids. This analysis also led the court to conclude that the ordinary meaning, aligned with the treaty's purpose, pointed to "the end of the accounting period in which the distribution of profits (dividend) takes place."

- Consistency and Conclusion: Finding that both the interpretation derived from the domestic context (via the official translation) and the interpretation based on ordinary meaning/object and purpose (via the authentic text and OECD materials) yielded substantially the same result, the court confirmed its interpretation. Since the Luxembourg parent had held the shares for more than six months prior to the end of the relevant accounting period (October 31, 2014), it met the holding period requirement.

Significance of the Court's Methodology

This decision is significant not just for its specific outcome regarding the Japan-Luxembourg treaty, but for its clear articulation of an interpretive methodology:

- Dual Analysis: The court systematically employed both a domestic-law contextual analysis (using the official translation) and an international-standard analysis (using ordinary meaning, object/purpose, and OECD materials).

- Elevation of OECD Commentary: It notably used the OECD Commentary not just as a supplementary means (Article 32) but as integral to discerning the ordinary meaning in light of the treaty's object and purpose (Article 31), arguably giving it a more central interpretive role than some previous jurisprudence might have suggested.

- Consistency Check: The court validated its conclusion by demonstrating consistency between the results derived from the domestic context and international standards.

Implications for U.S. Businesses

This case offers several important pointers for U.S. companies receiving dividends from Japanese subsidiaries:

- Scrutinize Treaty Requirements: Reduced withholding tax rates under treaties are valuable but often contingent on specific conditions like ownership percentages and holding periods. These must be carefully reviewed based on the precise wording of the applicable treaty (e.g., the Japan-U.S. treaty).

- Understand Holding Period Calculations: The critical date for calculating holding periods can vary based on treaty language. While many modern treaties refer to the date of dividend entitlement or span the payment date, older treaties or specific clauses (like the one in the Japan-Luxembourg treaty) might use different reference points, such as the end of the accounting period. This requires careful analysis, especially in the context of corporate reorganizations triggering deemed dividends.

- Navigating Interpretive Issues: Be aware that treaty interpretation can lead to disputes. Understanding the interpretive tools used by Japanese authorities and courts – including the Vienna Convention, the role of official Japanese translations, and the weight given to OECD materials – can help in assessing risks and formulating arguments.

- Deemed Dividends from Reorganizations: Remember that transactions like spin-offs, mergers, or share buybacks under Japanese law can result in deemed dividends subject to withholding tax. Ensure that treaty benefits, including holding period compliance, are considered for these events as well.

- Post-Judgment Developments: Following this Tokyo District Court decision, the Japanese National Tax Agency (NTA) issued a notice in February 2023 clarifying its administrative practice. It stated that for treaties with holding period language similar to the Japan-Luxembourg treaty (referencing "the end of the accounting period for which the distribution of profits takes place"), the holding period should indeed be calculated based on the end of that accounting period, aligning with the court's decision. This provides greater certainty for taxpayers under similarly worded treaties.

Conclusion

Tax treaties provide essential relief from double taxation and reduce withholding taxes on cross-border dividend flows, facilitating international investment. However, unlocking these benefits often requires careful navigation of specific treaty provisions, such as minimum holding period requirements designed to prevent abuse. The interpretation of these requirements demands a close reading of the specific treaty language and an understanding of applicable interpretive principles. The Tokyo District Court's February 2022 decision regarding the Japan-Luxembourg treaty offers a valuable illustration of a methodical approach, integrating domestic legal context with international standards derived from the Vienna Convention and OECD guidance. While the NTA's subsequent clarification provides helpful administrative certainty for similarly worded clauses, the case serves as a reminder for U.S. businesses of the importance of meticulous planning and seeking expert advice when managing dividend repatriations from Japan to ensure compliance and secure intended treaty benefits.