Deception, Consent, and Homicide: A Deep Dive into Japan's "Feigned Suicide Pact" Ruling

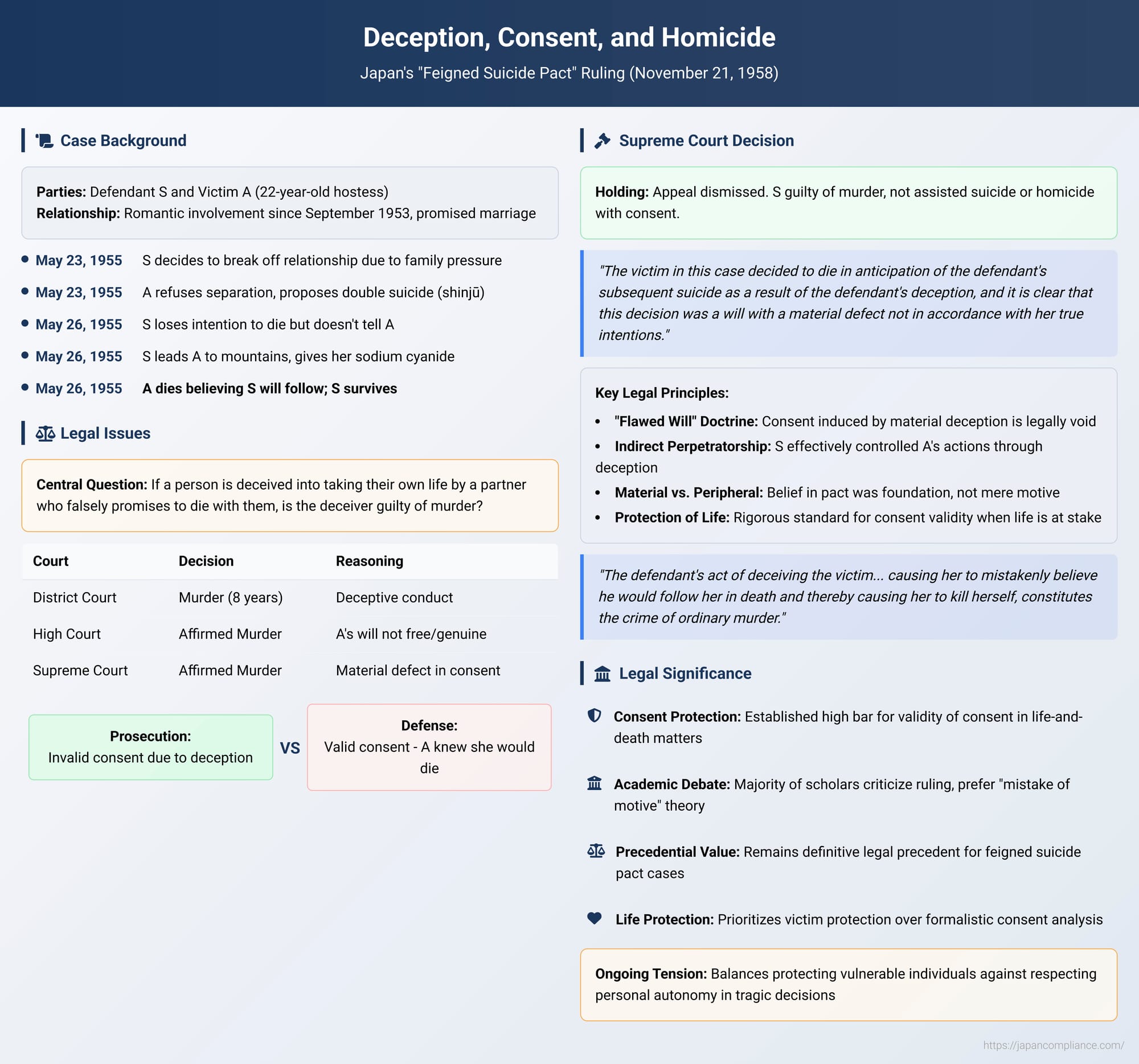

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of November 21, 1958. Case No. (A) 2220 of 1956.

Introduction

On November 21, 1958, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment that continues to be a cornerstone in the nation's criminal law jurisprudence, particularly concerning the concepts of consent and homicide. The case, involving a "feigned suicide pact," forced the judiciary to navigate the murky waters between murder and assisted suicide. It addressed a profound legal and ethical question: If a person is deceived into taking their own life by a partner who falsely promises to die with them, is the deceiver guilty of murder? The court's answer was a resounding yes, establishing a stringent standard for the validity of consent when a human life is at stake. This article explores the facts of this landmark case, the court's detailed reasoning, and the complex legal debates it has fueled for decades.

Factual Background

The case arose from a relationship between the defendant, a man referred to as S, and a 22-year-old woman, A, who worked as a hostess at a restaurant. Their involvement began around September 1953 and evolved into a serious romance, with the two eventually promising to marry. However, their relationship was fraught with difficulties. S had accumulated significant debt through his indulgent lifestyle, and his parents, strongly disapproving of his relationship with A, were pressuring him to end it.

Bowing to this pressure, S decided to break off the relationship and reform his life. Around May 23, 1955, he approached A to end their affair. A, however, refused to accept the separation. Instead, she passionately implored him that they should die together in a double suicide, or shinjū.

Caught between his family's demands and A's emotional plea, S found himself in a difficult position. He initially, and reluctantly, agreed to discuss the suicide pact, swayed by A's fervor. However, by May 26, his resolve had completely dissolved; he no longer had any intention of killing himself. Yet, he did not communicate this change of heart to A.

Instead, S saw an opportunity in A's unwavering belief that he loved her enough to die with her. He decided to exploit this trust. While feigning a shared commitment to death, he planned to have her die alone. On the afternoon of May 26, 1955, S led A to a mountainous area. He had purchased a lethal dose of sodium cyanide beforehand, which he carried with him. Believing that S would soon follow her, A accepted the poison from him and ingested it. She died from cyanide poisoning at the scene. S, having never intended to take his own life, survived.

Procedural History and the Lower Courts

The case was first heard at the Tanabe Branch of the Wakayama District Court. The court found S guilty of murder, not the lesser offense of assisting suicide. It sentenced him to eight years in prison, also considering a separate charge of embezzlement. S appealed the decision.

The Osaka High Court upheld the lower court's verdict. The High Court affirmed that S's actions constituted murder. The reasoning centered on the deceptive nature of his conduct. The court determined that A's decision to die was not a product of her own free and genuine will. Rather, it was induced by S's calculated deceit. He had orchestrated her death by creating a false reality. The defense, unsatisfied with this outcome, appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The defense's appeal to the Supreme Court rested on a central argument: A was fully aware that she was taking an action that would result in her own death. She recognized and consented to the act of dying. Therefore, her consent was legally valid, and S should have been convicted, at most, of a lesser offense like homicide with consent, not murder. The defense claimed the lower court had misinterpreted the law by classifying S's actions as murder.

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 21, 1958, unequivocally rejected this line of reasoning and dismissed the appeal.

The Court's rationale was meticulous. It began by distinguishing the present case from prior precedents. For instance, it referenced a 1933 case where a victim was deceived into believing that self-strangulation would only lead to a temporary state of suspended animation, not death. It also referenced a 1934 case involving a child who was incapable of understanding the concept of suicide. In those cases, the victims lacked a fundamental understanding of the fatal consequences of their actions, making a murder conviction straightforward.

The defense argued that the present case was different because A did understand she was going to die. Her mistake was merely about a collateral matter—S's subsequent action. The Supreme Court disagreed profoundly.

The core of the Court's ruling was its assessment of A's consent. It stated:

"The victim in this case decided to die in anticipation of the defendant's subsequent suicide as a result of the defendant's deception, and it is clear that this decision was a will with a material defect not in accordance with her true intentions."

The Court declared that A's consent was fundamentally vitiated by S's fraud. The belief that S would join her in death was not a mere "motive" or peripheral reason for her decision. It was the very foundation of her resolve. Had she known that S had no intention of dying, she would not have consented. The deception went to the heart of her decision-making process, creating what the Court deemed a "material defect" in her will.

Therefore, because her consent was legally invalid, it could not be used to mitigate the charge from murder. The Court concluded:

"Thus, the defendant's act of deceiving the victim, despite having no intention of committing suicide himself, causing her to mistakenly believe he would follow her in death and thereby causing her to kill herself, constitutes the crime of ordinary murder... The original judgment is correct, and the appellant's argument is without merit."

The Court held that using deception as a tool to bring about another's death is functionally equivalent to other methods of killing. S's scheme was merely the means by which he executed the act of murder.

In-Depth Legal Analysis: The Contours of Consent in Japanese Criminal Law

The 1958 ruling has become a seminal case because it delves deep into the interpretation of Article 202 of the Japanese Penal Code, which sets out lesser penalties for homicide committed upon request or with the consent of the victim, as well as for aiding or instigating suicide. The conviction hinges on the presence of a "valid consent" from the victim. This case essentially defined the boundaries of what constitutes such consent.

The "Flawed Will" Doctrine vs. "Mistake of Motive"

The Supreme Court's decision established what can be called the "flawed will" doctrine. It posits that consent induced by deception regarding a matter material to the decision is legally void. The court viewed A's belief in the "pact" not as a simple motive, but as an indispensable condition for her consent.

However, this position has been the subject of extensive academic debate. A prominent counterargument is the "mistake of motive" theory. Proponents of this view argue that the court's analysis was flawed. In their view, A made a conscious and informed decision to end her life. She understood the act and its irreversible consequence. Her reason for doing so—her motive—was the belief that her lover would follow. While this motive was based on a falsehood, the core consent to the act of dying remained intact. According to this theory, the mistake pertained to a future event external to the act of self-termination, and thus should not invalidate the consent itself. Following this logic, S's crime should have been homicide with consent or assisting suicide under Article 202, which carries a significantly lighter sentence than murder under Article 199.

Another related academic perspective is the "legal interest" theory. This theory argues that for consent to be invalidated by a mistake, the mistake must concern the legal interest being harmed. In this case, the legal interest was A's own life. The mistake she made was about S's intentions regarding his life. Since the error did not pertain directly to her own physical existence, her consent to end it should be considered valid.

The Second Hurdle: The Doctrine of Perpetratorship

Even if one accepts the Court's position that A's consent was invalid, a second legal question arises: Was S the actual perpetrator of the murder? After all, A was the one who performed the physical act of swallowing the poison. This introduces the complex legal doctrine of the "indirect perpetrator" (kansetsu seihan).

The theory of indirect perpetratorship holds a person (the "principal") criminally liable for an act committed by another person (the "instrument") if the principal effectively controlled the instrument's actions. This typically applies when the instrument lacks criminal capacity (e.g., is a child or mentally incapacitated) or criminal intent.

The Supreme Court's ruling implicitly treats S as an indirect perpetrator. It views his deception as a form of control so complete that it rendered A a mere instrument in the commission of her own death. He masterminded the entire event, and his fraudulent promise was the weapon he used to achieve the fatal result.

However, this aspect of the ruling is also heavily debated. Many legal scholars argue that for indirect perpetratorship to apply in a case of suicide, the level of control or coercion must be exceptionally high, effectively negating the victim's free will. Critics question whether S's deception, while morally reprehensible, rose to this level. A was an adult with full mental capacity. She made a choice, albeit one based on tragic misinformation. Some argue that this scenario is more accurately described as instigating or aiding a suicide, where the final, autonomous act of the victim remains central. They contend that only in cases involving extreme psychological manipulation, exploitation of a vulnerability, or coercion could the deceiver be classified as a murderer.

The Legacy and Modern View

The 1958 "feigned suicide pact" judgment remains the definitive legal precedent in Japan for such cases. It stands for the principle that the law will rigorously protect the sanctity of life by refusing to recognize consent that is procured through material deception. It reflects a judicial posture that prioritizes the protection of the victim over a more formalistic analysis of consent.

Despite its status as binding precedent, a significant portion, if not a majority, of contemporary legal academics in Japan are critical of the ruling. The arguments that the victim's error was one of motive and that the criteria for indirect perpetratorship were not met are widely supported in scholarly circles. This ongoing debate highlights the dynamic tension in criminal law between protecting vulnerable individuals and respecting the autonomy of personal decisions, even when those decisions are tragic and ill-advised.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1958 decision is far more than a simple murder conviction. It is a profound statement on the nature of human will and the legal limits of consent. By classifying the act of feigning a suicide pact as murder, the court established an exceptionally high bar for the validity of consent in matters of life and death. It determined that consent cannot be divorced from the circumstances and beliefs under which it is given. When deception fundamentally shapes the decision to die, the law will view the deceiver not as an assistant to a suicide, but as the author of a homicide. The case continues to serve as a crucial, if controversial, landmark, raising enduring questions about autonomy, deception, and where ultimate responsibility lies when one person's lie leads to another's death.