Deceiving the Court: A Japanese Ruling on the Limits of Litigation Fraud

Can you commit fraud by tricking a court? The concept of "litigation fraud"—using lies, forged evidence, or false testimony to obtain a favorable judgment and thereby take property from an opponent—is a recognized crime in many legal systems. In Japan, it is typically prosecuted under the general fraud statute. However, the unique nature of the court as the "deceived party" creates complex legal questions about the crime's proper scope.

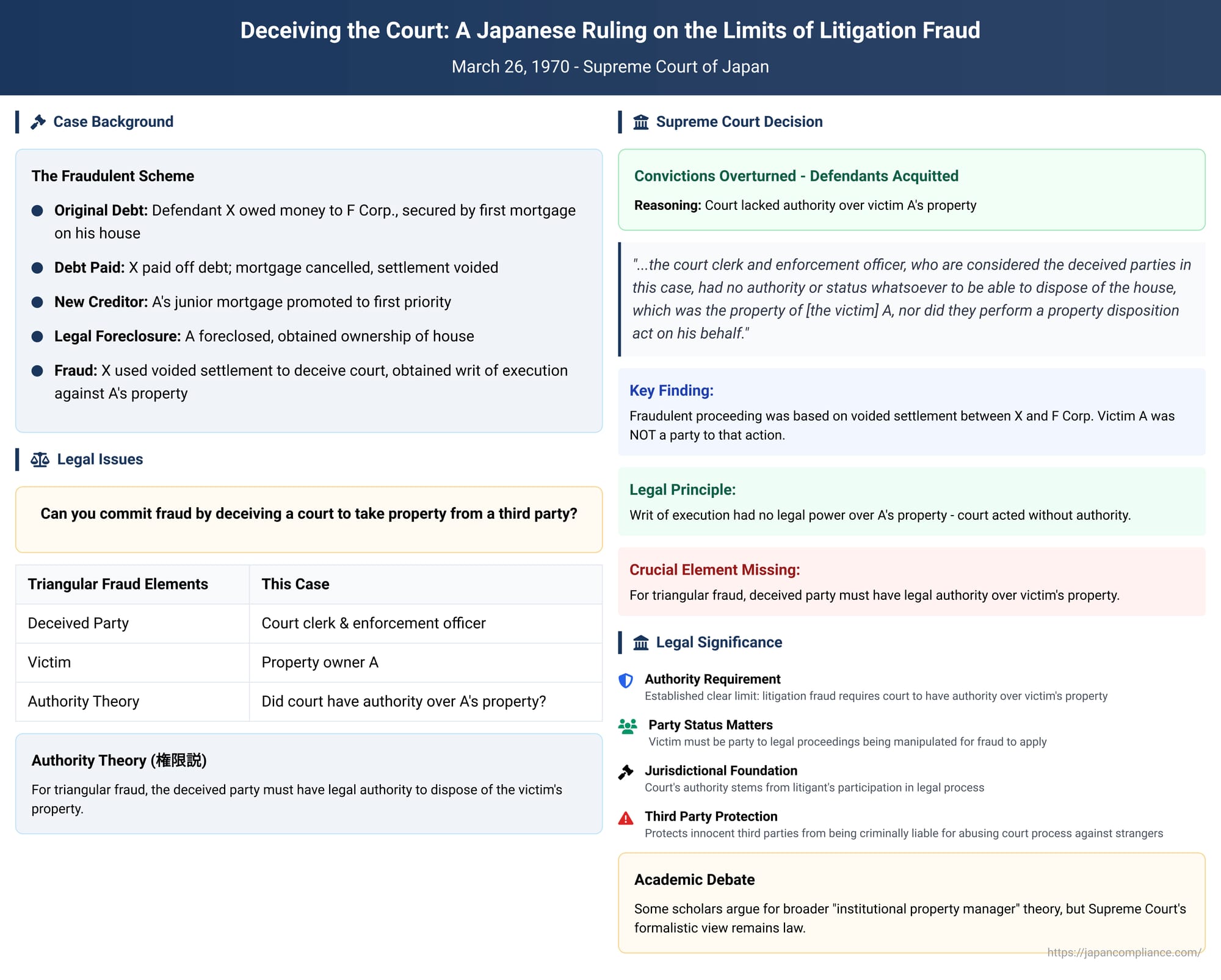

A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 26, 1970, established a crucial limit on the crime of litigation fraud. The case, which involved an elaborate scheme to fraudulently repossess a house, hinged on a subtle but powerful legal question: for the crime of fraud to be established, must the deceived party (the court) have the legal authority to dispose of the victim's property? The Court's answer was a resounding "yes," and its reasoning provides a foundational framework for understanding this unique form of fraud.

The Facts: An Elaborate Scheme to "Retake" a House

The facts of the case are complex, involving a chain of property rights and a clever manipulation of the legal process.

- The Original Debt: A man, defendant X, had previously owed money to a company, F Corp. This debt was secured by a first mortgage on his house and was formalized in a court-mediated settlement.

- The Debt Paid: X later paid off this debt in full. As a result, the mortgage was cancelled, and the court settlement document became legally void and unenforceable.

- A New Creditor: In the meantime, a second creditor, A, had secured a junior mortgage on the same house. When the first mortgage to F Corp. was cancelled, A's mortgage was automatically promoted to first priority.

- The Legal Foreclosure: A, now the primary mortgage holder, legally foreclosed on the property due to his own claims against X. Through proper court proceedings, A obtained an ownership transfer registration and took legal possession of the house. At this point, the house legally belonged to A.

- The Fraudulent Scheme: Defendant X, now with no legal claim to the house, conspired with his wife and others to "retake" it. They took the old, voided settlement document between X and F Corp. and went back to court. They presented this defunct document to a court clerk, B, pretending it was still a valid debt. Deceived, the clerk issued a "writ of execution." They then presented this fraudulent writ to a court enforcement officer, C. Deceived in turn, the officer initiated a forcible execution. Acting under the color of law, the officer went to the house and transferred possession from the true owner, A, to F Corp. (who was now colluding with X).

The defendants were charged with and convicted of fraud for having "defrauded" A of his house. They appealed, arguing that their actions did not legally constitute fraud.

The Legal Framework: "Triangular Fraud" and the "Authority Theory"

This case is a classic example of what is known in criminal law as "triangular fraud" (sankaku sagi). This is a scenario where the person who is deceived is different from the person who suffers the financial loss. Here, the deceived parties were the court officials (the clerk and the enforcement officer), but the victim who lost his property was the true owner, A.

To determine if such a scenario constitutes fraud, Japanese law often applies the "Authority Theory" (kengen-setsu). This theory holds that for triangular fraud to be established, the deceived party must have the legal authority or status to dispose of the victim's property. For example, a bank teller who is tricked into giving away the bank's money commits fraud because the teller has the authority to dispose of the bank's assets. If a person with no such authority is deceived, the crime of fraud is not established.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Authority, No Fraud

Applying the "Authority Theory" to the facts, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions and acquitted the defendants. The Court's reasoning was a precise application of legal principles.

- The Deceived Parties: The court clerk and the enforcement officer.

- The Victim: The true owner of the house, A.

- The Fatal Flaw: The fraudulent legal proceeding was based on an old, voided settlement between X and F Corp. The victim, A, was not a party to that original action. The writ of execution that the court officials acted upon was legally effective only against the named debtor, X. It had no legal power or effect whatsoever over A or A's property.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded:

"...the court clerk and enforcement officer, who are considered the deceived parties in this case, had no authority or status whatsoever to be able to dispose of the house, which was the property of [the victim] A, nor did they perform a property disposition act on his behalf."

Because the deceived party (the court) lacked the necessary legal authority over the victim's property, a crucial element of triangular fraud was missing. The defendants' actions were wrongful, but they did not fit the legal structure of the crime of fraud.

Analysis: The Court's Role in Litigation Fraud

This 1970 decision establishes a vital principle: for litigation fraud to be established, the victim must be a party to the legal proceedings that are being manipulated. When a person is a defendant in a lawsuit, they are subject to the court's jurisdiction. If their opponent uses deception to win that lawsuit, the court has the legal authority to issue a judgment that disposes of the losing party's property. In that common scenario, litigation fraud is clearly established.

However, this case involved a different and more insidious scheme. The defendants manipulated the court system to take action against a person, A, who was a complete stranger to the legal proceedings they were abusing. The court was acting on a case between X and F Corp.; its power did not extend to A.

The theoretical underpinning of this is the idea that a court's authority to dispose of a litigant's property stems from the litigant's participation—whether voluntary or not—in the legal process. By being a party to a lawsuit, one implicitly submits to the court's power to render a binding judgment. But when the victim is not a party, no such submission or grant of authority exists.

Some scholars have critiqued this view, arguing for a broader understanding of the court's role. They suggest that courts function as "institutional property managers" for society, and that deceiving this institutional manager should always be a crime, regardless of whether the victim was a formal party to the specific action. However, the Supreme Court's narrower, more formalistic view remains the law in Japan.

Conclusion: A Crucial Limit on the Crime of Litigation Fraud

The Supreme Court's 1970 ruling is a foundational decision that sets a clear and logical boundary for the crime of litigation fraud. It affirms that to convict a person for deceiving a court, the prosecution must show not only that the court was tricked, but that the court had the legal authority to dispose of the actual victim's property.

This authority exists when the victim is a legitimate party to the lawsuit being manipulated. But when a perpetrator abuses the legal system to take action against a third party who is a stranger to those proceedings, the court acts without authority, and the perpetrator's act, while wrongful, does not constitute the crime of fraud. The decision ensures that the powerful charge of fraud is correctly applied only when the deceived party and the victim are linked by a legally recognized relationship of authority.