Debtor's Possession After Seizure of Movables: A 1959 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Case Name: Objection to Compulsory Execution

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 32 (O) No. 1140

Date of Judgment: August 28, 1959

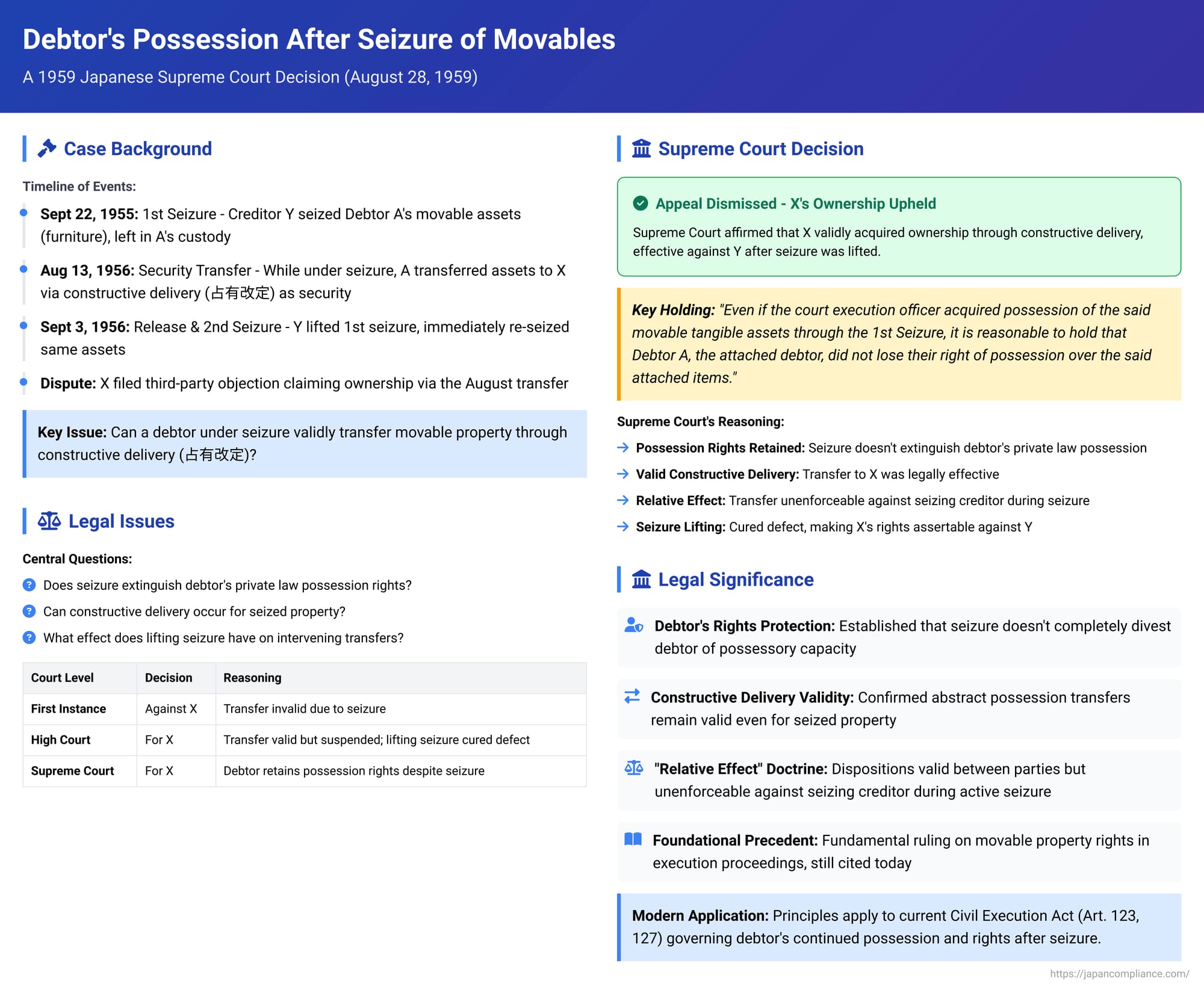

This article examines a foundational Japanese Supreme Court judgment from August 28, 1959. The case clarifies the extent of a debtor's possessory rights over movable property (such as household furniture) after it has been seized by a court execution officer, particularly when the property remains in the debtor's custody. It addresses whether the debtor can still validly transfer such property to a third party by way of constructive delivery (sen'yū kaitei).

Factual Scenario: Seizure, Transfer, Release, and Re-Seizure

The events leading to the Supreme Court's decision were as follows:

- First Seizure: On September 22, 1955, Creditor Y, holding an enforceable judgment against Debtor A, had Debtor A's movable tangible assets (furniture and other items) seized by a court execution officer (shikkōri, the term then used for what is now shikkōkan). This is referred to as the "1st Seizure." The seized items were presumably left in Debtor A's custody, marked as seized.

- Intervening Transfer for Security: On August 13, 1956, while the 1st Seizure was still in effect, Debtor A entered into an agreement with Mr. X (the plaintiff and respondent in the Supreme Court). To secure a debt owed to Mr. X (arising from a loan for consumption by way of novation, jun shōhi taishaku), Debtor A purported to sell the seized assets to Mr. X. Simultaneously, it was agreed that Debtor A would lease these assets back from Mr. X without charge. The "delivery" of these assets from A to X was effected by way of "constructive delivery" (sen'yū kaitei), a method where the transferor (A) continues to physically possess the goods but now does so on behalf of the transferee (X). This arrangement constituted a security assignment (jōto tanpo).

- Release and Second Seizure: On September 3, 1956, Creditor Y, reportedly for procedural reasons, had the 1st Seizure formally lifted. Immediately on the same day, Creditor Y initiated a new seizure of the very same assets based on the same enforceable judgment against Debtor A. This is referred to as the "2nd Seizure."

- Third-Party Objection: Mr. X filed a third-party objection lawsuit (daisansha igi no uttae) against the 2nd Seizure. Mr. X asserted his ownership rights over the assets, claiming these rights were established by the security assignment and constructive delivery from Debtor A on August 13, 1956. Creditor Y countered that the transfer from A to X was void because the assets were under the 1st Seizure at the time of the purported transfer, and the subsequent lifting of that seizure could not validate an initially void act.

The Legal Conundrum: Can a Debtor Under Seizure Transfer Possession?

The central legal questions were:

- Does a debtor lose their private law right of possession (sen'yūken) over movable property when it is seized by a court execution officer, especially if the property remains in the debtor's physical custody?

- Can a debtor validly transfer ownership and effect delivery of such seized property to a third party using constructive delivery (sen'yū kaitei)?

- What is the legal effect of the subsequent lifting of the initial seizure on such an intervening transfer?

The High Court's Reasoning

The Fukuoka High Court, overturning the first instance court, had ruled in favor of Mr. X. It determined that:

- The disposition of property under seizure is not absolutely prohibited nor is such a disposition absolutely void.

- While the disposition is valid, its effect cannot be asserted against the seizing creditor as long as the seizure remains in effect. This interpretation was supported by the intent of the (then) Code of Civil Procedure Article 650.

- If the seizure is lifted before an auction takes place, the third party's acquisition of ownership becomes assertable even against the creditor who initiated the (now lifted) seizure, as if the seizure had never occurred.

- The High Court also recognized the validity of the constructive delivery from Debtor A to Mr. X.

Creditor Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that since the execution officer possessed the seized items, Debtor A could not have effected a valid delivery to Mr. X.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

On August 28, 1959, the Supreme Court dismissed Creditor Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's judgment in favor of Mr. X.

The Supreme Court's key finding was:

"Even if the court execution officer acquired possession of the said movable tangible assets through the 1st Seizure, it is reasonable to hold that Debtor A, the attached debtor, did not lose their right of possession (sen'yūken) over the said attached items."

Based on this, the Court concluded:

"Therefore, the transfer of the said items between A and X, and the delivery thereof by way of constructive possession, while it could not be asserted against Creditor Y, the seizing creditor, during the subsistence of the seizure, is a separate matter. As a result of the 1st Seizure being lifted, X became able to assert against Y the acquisition of ownership of the said items through the aforementioned transfer and delivery. The High Court's judgment, being to the same effect, can be affirmed as just."

Analysis and Significance

This 1959 Supreme Court decision is a foundational ruling on the nature of a debtor's possession after movable property has been seized but left in their custody.

- Debtor's Enduring Possessory Rights: The judgment clearly establishes that the act of seizure by a court execution officer does not extinguish the debtor's underlying private law right of possession, particularly when the seized goods remain physically with the debtor (often under seal or other indication of seizure, as per then-current practice, now formalized in Civil Execution Act Art. 123(3)).

- Validity of Constructive Delivery (Sen'yū Kaitei): The Court affirmed that constructive delivery (Civil Code Art. 183) – where a seller/transferor retains physical control but holds the goods for the buyer/transferee – is a valid method for a debtor to transfer possession of seized movables to a third party. This is significant because constructive delivery is a highly abstract form of possession transfer.

- "Relative Effect" of Seizure (Procedural Unenforceability): The act of transferring seized property is not void ab initio. Instead, its effect is "suspended" or unenforceable against the seizing creditor while the seizure is active. This is often referred to as the "relative effect of seizure" (tetsuzuki sōtaikō), meaning the disposition is valid between the debtor and the third party but cannot prejudice the seizing creditor's rights under the ongoing execution.

- Effect of Lifting the Seizure: The lifting of the initial seizure is a critical event. Once the seizure is removed, the prior "defect" in assertability against the seizing creditor is cured. The third party's ownership, acquired through the earlier valid (though temporarily restricted) transfer, becomes fully effective and can be asserted even against the original seizing creditor if that creditor later attempts to re-seize the same goods based on the same debt.

- Theories on the Execution Officer's Possession: Legal commentary surrounding this decision often discusses two main theories regarding the legal nature of the possession acquired by the execution officer:The Supreme Court in this 1959 judgment did not explicitly adopt or reject either specific theory. However, its conclusion that the debtor does not lose their right of possession is compatible with outcomes under both general approaches, as both ultimately recognize that the debtor is not entirely divested of all possessory capacity. The practical outcomes regarding the debtor's ability to perform acts like constructive delivery or a third party's ability to acquire rights (subject to the seizure's effect) tend to converge regardless of the chosen theoretical label.

- Public Law Possession Theory: Historically the dominant view of the pre-war Great Court of Cassation. This theory holds that the officer's possession is a distinct act of public authority, entirely separate from and not affecting the debtor's private law possession.

- Private Law Possession Theory: This view posits that the officer's possession also has private law characteristics. Within this theory, variations exist: some argued the officer gains direct possession and the debtor becomes an indirect possessor; others, particularly for cases where goods remain with the debtor, suggest the debtor retains direct possession while the officer holds indirect possession, or that the debtor acts as a possessory assistant for the officer.

- Broader Implications: The principles from this case have broader implications. It is generally accepted that even after seizure of movables:

- The debtor can still effect a delivery that satisfies the requirements for transferring title under Civil Code Article 178.

- Acquisitive prescription running in favor of the debtor is not interrupted by the seizure (Civil Code Art. 164).

- The debtor can bring possessory actions (Civil Code Art. 197) if the seized goods are unlawfully taken by someone other than the execution officer.

(The current Civil Execution Act, in Art. 127, provides a mechanism for the execution officer to recover seized goods if a third party takes them, based on an order from the execution court.)

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1959 decision robustly affirmed a debtor's capacity to deal with seized movable property remaining in their custody, particularly through constructive delivery. While such dispositions are unenforceable against the seizing creditor as long as the seizure is active, they are not inherently void. The subsequent lifting of the seizure validates the transfer's effectiveness even against that creditor. This judgment underscores that seizure primarily imposes a procedural restriction on disposal relative to the execution proceedings, rather than completely extinguishing the debtor's underlying possessory rights and capacity to transfer those rights.