Japan Supreme Court Approves Survivor Pension for Uncle‑Niece De Facto Marriage (2007)

TL;DR

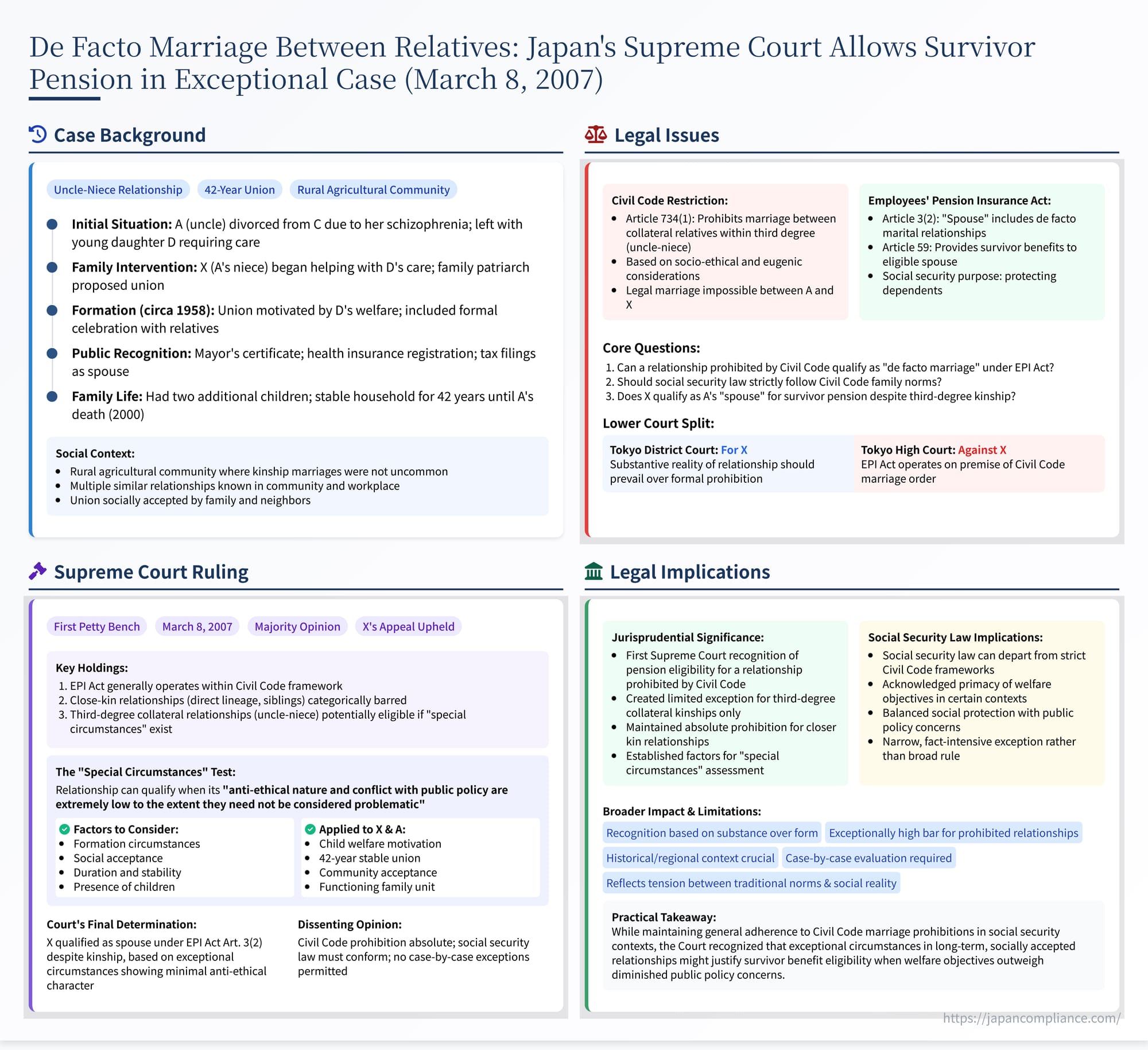

- Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 8 Mar 2007 (H17 (Gyo‑Hi) 354)

- Issue: Can an uncle‑niece de facto marriage qualify a surviving partner for Employees’ Pension Insurance benefits despite Civil Code Art. 734?

- Holding: Yes—in highly exceptional circumstances. The Court created a “special‑circumstances” test for third‑degree relatives where public‑policy conflict is “extremely low.”

- Key Factors: 42‑year stable union, child‑care motive, community acceptance, harmonious family life.

- Limit: No relaxation for closer kin (lineal relatives or siblings); test is fact‑intensive and narrow.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Union Born of Circumstance

- Legal Framework and the Dispute Over Survivor Benefits

- Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Interpretations

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 8, 2007)

- The Dissenting Opinion

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On March 8, 2007, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a highly significant and nuanced judgment concerning eligibility for survivor benefits under the Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act) (Case No. 2005 (Gyo-Hi) No. 354, "Survivor Employees' Pension Non-Payment Decision Revocation Case"). The case presented the difficult question of whether a person in a long-standing, stable de facto marital relationship could qualify as a surviving "spouse" for pension purposes, even though the relationship was between an uncle and niece – a kinship degree within which legal marriage is prohibited by Japan's Civil Code. Departing from a strict application of the Civil Code prohibition in the social security context, the Court found that under exceptional circumstances demonstrating minimal anti-ethical character and strong social acceptance, such a de facto spouse could indeed be eligible. This ruling delves into the complex interplay between family law norms, social realities, and the objectives of social security legislation.

Factual Background: A Union Born of Circumstance

The facts presented to the court painted a picture of a unique family situation shaped by hardship and community context:

- Initial Family Situation: A (born 19XX) lived in Town C, Prefecture A, with his parents (including father B, the appellant X's grandfather), brother, and sister. A married C in 19XX, and they had a daughter, D, later that year. However, around the time of D's birth, C began suffering from schizophrenia and returned to her parents' home, leaving D behind.

- Failed Divorce and Caregiving Challenges: A concluded that continuing the marriage with C was impossible and sought a divorce. However, negotiations proved difficult due to C's mental state and demands from C's parents (who wanted A to marry C's sister after the divorce, which A refused out of concern for C). This stalemate lasted for four years. During this time, A worked at employer E. Since A worked, including night shifts, the care of his young daughter D fell primarily to A's elderly parents (B and his wife), who were busy running the family farm and could not provide fully adequate care. D suffered from poor nutrition and lacked sufficient attention to her clothing and hygiene.

- X Steps In: The appellant, X (born 19XX), was A's niece (the daughter of A's older brother). During school holidays, X would visit her grandparents' (B's) home to help out. She began taking care of D, changing diapers, doing laundry, and providing attention. D became very attached to X, more so than to any other relative.

- The Proposal: A's father, B, acting somewhat as the family patriarch, observed D's attachment to X. Considering several factors – A's likelihood of inheriting the family farm (making a relative desirable as a spouse), X's age proximity to A, the difficulty A faced in finding a new wife given his circumstances (existing child, night shifts, the burden of caring for elderly parents and farm work) – B proposed that A and his niece X should marry or form a union.

- Formation of the De Facto Marriage: X, initially surprised by the proposal due to the close kinship, was moved by sympathy for D's condition (thin, neglected clothes). She decided to enter the union for D's sake. Around the end of Month XX, Showa XX (likely 1958, based on the later stated duration of 42 years), X and A began living together as husband and wife. They marked the beginning of their life together with a short honeymoon trip and a celebratory gathering with relatives, significantly mediated by the same relative who had mediated A's first marriage to C.

- Formal Divorce and Public Acknowledgment: A eventually finalized his divorce from C in Month XX, Showa XX. To facilitate practical matters like tax deductions and birth allowances for children they later had, A obtained a certificate from the mayor of Town C, attested to by two witnesses and A's workplace superior (the stationmaster), certifying that A and X were married. X was listed as A's spouse on his health insurance card and for spousal deductions on tax forms. When X gave birth, the relevant Mutual Aid Association (presumably related to employer E) provided maternity benefits.

- A Long and Stable Family Life: X and A lived together as a family continuously for approximately 42 years, until A's death in Heisei 12 (2000). They had two children together, F (born Showa XX) and G (born Showa XX), both of whom A legally acknowledged as his own. The household, consisting of A, X, A's daughter D, and their children F and G, was described as harmonious, supported by A's income, with X managing domestic affairs. X consistently fulfilled the role of A's wife, including acting as chief mourner at his funeral. A had also instructed X on how to handle pension procedures after his death, providing her with relevant documents.

- Social Context: The judgment noted the social context: the family lived in a region where agriculture was prevalent, and marriages between relatives were reportedly not uncommon, partly due to needs like keeping farmland within the family or finding suitable partners in rural communities. X was aware of other cousin marriages within her close relatives and at least three other uncle-niece de facto relationships (two at A's workplace, one among relatives).

Legal Framework and the Dispute Over Survivor Benefits

Following A's death in 2000, X applied for Survivor Employees' Pension benefits from the appellee, Y (the Social Insurance Agency Director-General, responsible for administering the EPI), claiming she qualified as A's surviving spouse.

The Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act) provides survivor benefits to certain dependents of a deceased insured person. Key provisions include:

- Eligible Survivors: Article 59(1) lists eligible survivors, primarily including the spouse, children, parents, etc., who were financially dependent on the deceased at the time of death.

- Definition of "Spouse": Article 3(2) defines "spouse" to include not only the legally registered spouse but also a person "in circumstances similar to a de facto marital relationship although the marriage has not been registered" (事実上婚姻関係と同様の事情にある者 - jijitsujō kon'in kankei to dōyō no jijō ni aru mono). This explicitly recognizes stable, marriage-like de facto relationships (内縁 - nai'en).

However, Japan's Civil Code imposes restrictions on who can marry. Article 734(1) prohibits marriage between lineal blood relatives and between collateral blood relatives within the third degree of kinship. An uncle-niece relationship falls under this third-degree collateral kinship prohibition.

Y denied X's application, citing the Civil Code prohibition. Y argued that because X and A could not have legally married, their de facto relationship, despite its duration and stability, was contrary to public order and morals inherent in the Civil Code's marriage framework, and thus could not be recognized as qualifying under EPI Act Art. 3(2).

Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Interpretations

The case saw conflicting outcomes in the lower courts:

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): Ruled in favor of X, finding that eligibility under EPI Act Art. 3(2) should depend on the substantive reality of the relationship (duration, stability, shared life, children, social acceptance) and the specific circumstances, rather than being automatically barred by the Civil Code prohibition. The court found X and A's 42-year relationship met the substantive requirements of a de facto marriage deserving protection.

- Second Instance (Tokyo High Court): Reversed the District Court's decision, siding with the Social Insurance Agency (Y). The High Court held that the EPI Act operates under the premise of the Civil Code's marriage order. Protecting a relationship explicitly prohibited by the Civil Code for public policy reasons (social ethics, eugenics) would be inconsistent with this premise. Therefore, X could not qualify as a de facto spouse under the EPI Act.

X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 8, 2007)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated March 8, 2007, overturned the High Court's ruling and ultimately found in favor of X, albeit based on specific, exceptional circumstances. The majority opinion carefully navigated the tension between the Civil Code's marriage prohibitions and the social security objectives of the EPI Act.

1. Balancing Social Security Goals and Civil Law Order:

The Court acknowledged that the EPI system, as a public pension scheme funded by compulsory contributions and state subsidies, generally operates within the framework established by the Civil Code regarding family relationships. It agreed with the High Court that, as a general rule,内縁 relationships that fundamentally contradict the Civil Code's marriage order cannot be recognized for survivor benefit purposes.

2. Rationale and Severity of Kinship Prohibitions:

The Court recognized that the Civil Code's prohibition on close-kin marriage (Art. 734) is based on significant public policy considerations involving "socio-ethical considerations and eugenic considerations." The Court explicitly stated that relationships between direct blood relatives (parent-child, grandparent-grandchild) and between siblings (second-degree collateral relatives) possess an "extremely high" degree of anti-ethical character and conflict with public policy under current Japanese social norms. Such relationships, the Court indicated, could not be recognized under EPI Act Art. 3(2), regardless of how stable or marriage-like they appeared externally.

3. Potential Exception for Third-Degree Collateral Kinship:

However, the Court drew a distinction when it came to third-degree collateral relationships (such as uncle-niece or aunt-nephew). While affirming that these relationships also generally carry the anti-ethical and anti-public policy character derived from the Civil Code prohibition, the Court opened the possibility for exceptions under specific conditions.

4. The "Special Circumstances" Test:

The Court established a test based on "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō). It held that even though a de facto marriage exists between third-degree collateral relatives (prohibited from marrying by Civil Code Art. 734(1)), the surviving partner can still be recognized as an eligible spouse under EPI Act Art. 3(2) if the relationship's "anti-ethical nature and conflict with public policy are extremely low to the extent that they need not be considered problematic" from the perspective of maintaining marriage order and other relevant public interests.

Determining whether these "special circumstances" exist requires a holistic evaluation of factors including:

- The circumstances and motivations leading to the formation of the relationship.

- The perception and acceptance of the relationship by relatives and the surrounding community.

- The duration of the shared life.

- The presence and upbringing of children.

- The overall stability and functioning of the relationship as a marital/family unit.

If these factors demonstrate that the relationship, despite the kinship impediment, functioned essentially as a socially accepted, long-term, stable family unit, and that its anti-ethical character is negligible in context, then the social security purpose of protecting the surviving family member should prevail over the general policy behind the marriage prohibition.

5. Application to X and A's Relationship:

Applying this test to the specific facts, the Court found that X and A's relationship did present such "special circumstances":

- Formation: It originated primarily from a need to care for A's young child, D, a motivation arguably mitigating the anti-ethical concerns.

- Social Acceptance: The relationship was publicly acknowledged through various means (celebratory gathering, mayor's certificate, workplace/insurance records) and seemingly accepted without significant resistance by relatives and the local community, potentially influenced by regional customs regarding kinship marriage.

- Duration and Stability: The relationship lasted approximately 42 years, demonstrating exceptional stability and permanence.

- Family Unit: They raised three children together (D, F, and G) in what was described as a harmonious family life, with X fulfilling the role of wife and mother.

- Conclusion: Based on this totality of circumstances, the Court concluded that the anti-ethical/anti-public policy nature of this specific uncle-niece de facto marriage was "extremely low to the extent that it need not be considered problematic."

Final Ruling on Eligibility: Therefore, the "special circumstances" warranted prioritizing the EPI Act's purpose of providing survivor protection. The fact that X and A were uncle and niece did not, in this specific case, bar X from being recognized as a person "in circumstances similar to a de facto marital relationship" under EPI Act Art. 3(2). X was thus deemed an eligible spouse entitled to survivor benefits.

The Dissenting Opinion

One Justice dissented, arguing for a stricter adherence to the Civil Code's prohibition.

- The dissent contended that Civil Code Art. 734(1) provides an absolute bar to marriage between third-degree collateral relatives, without exceptions.

- It argued that the EPI Act operates on the premise of this Civil Code order, and there is no explicit provision allowing this premise to be relaxed based on individual circumstances.

- The dissent questioned the majority's approach of evaluating the degree of anti-ethical character, suggesting the prohibition itself reflects a definitive public policy judgment that shouldn't be weighed against other factors on a case-by-case basis in the social security context.

- It concluded that since the relationship violated the Civil Code's marriage prohibition, X could not qualify under EPI Act Art. 3(2), and the agency's decision denying benefits was lawful.

Implications and Significance

This landmark 2007 decision marked a significant development in Japanese social security law concerning family relationships:

- First Recognition for Prohibited Kinship: It was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly recognize the possibility of survivor pension eligibility for a de facto spouse in a relationship prohibited by the Civil Code's kinship rules (specifically, third-degree collateral).

- Highly Exceptional Circumstances Required: The ruling is narrow and heavily fact-dependent. It does not create a general rule allowing pensions for all uncle-niece de facto relationships. Eligibility requires demonstrating "special circumstances" that render the relationship's conflict with public policy "extremely low" – a high bar likely met only in cases with long duration, stability, strong social acceptance (especially in specific historical/regional contexts), and often involving factors like child welfare.

- Reinforces Bar for Closer Kin: The Court explicitly distinguished third-degree collateral relationships from closer kinship ties (direct lineage, siblings), indicating that de facto relationships within those closer degrees remain absolutely barred from recognition for pension purposes due to their perceived severe conflict with public policy.

- Social Security Law's Autonomy: The decision affirms that while social security law generally respects the Civil Code framework, it can depart from strict civil law definitions when necessary to achieve its distinct social welfare objectives, particularly in interpreting terms like "spouse" to include de facto relationships.

- Ongoing Issues: The case highlights the ongoing legal and social challenges surrounding the definition of "family" and the recognition of diverse relationship structures within Japan's legal and social security systems. While providing a path for recognition in exceptional cases like X's, it maintains the general prohibition based on Civil Code norms.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 8, 2007 judgment demonstrated a willingness to look beyond strict legal formalities in exceptional circumstances to achieve the social protection goals of the Employees' Pension Insurance system. While upholding the general principle that relationships prohibited by the Civil Code's kinship rules are typically not recognized for survivor pension benefits, the Court carved out a narrow exception for third-degree collateral relationships (like uncle-niece). Where "special circumstances" – such as the relationship's formation history, long-term stability, social acceptance, and functioning as a family unit – render its conflict with public policy extremely low, the surviving de facto partner may be deemed eligible for survivor benefits. This decision underscores the careful balancing act between respecting established family law norms and fulfilling the social security mandate to protect vulnerable surviving family members based on the substantive reality of their lives.

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Japan Supreme Court 2017 Survivor‑Pension Case: Why Age Rules for Widowers Survived an Equality Challenge

- Student Disability Pension Gap: Why Japan’s Supreme Court Backed Voluntary Enrollment (2007)

- Supreme Court of Japan – Decision Database: Survivor Employees’ Pension Non‑Payment Case (March 8 2007)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare – Pension Policy Overview

- Outline of the Employees’ Pension Insurance Act (PDF, MHLW)