De Facto Divorce & Survivor Pensions: Japan Supreme Court’s Landmark 1983 Ruling

TL;DR

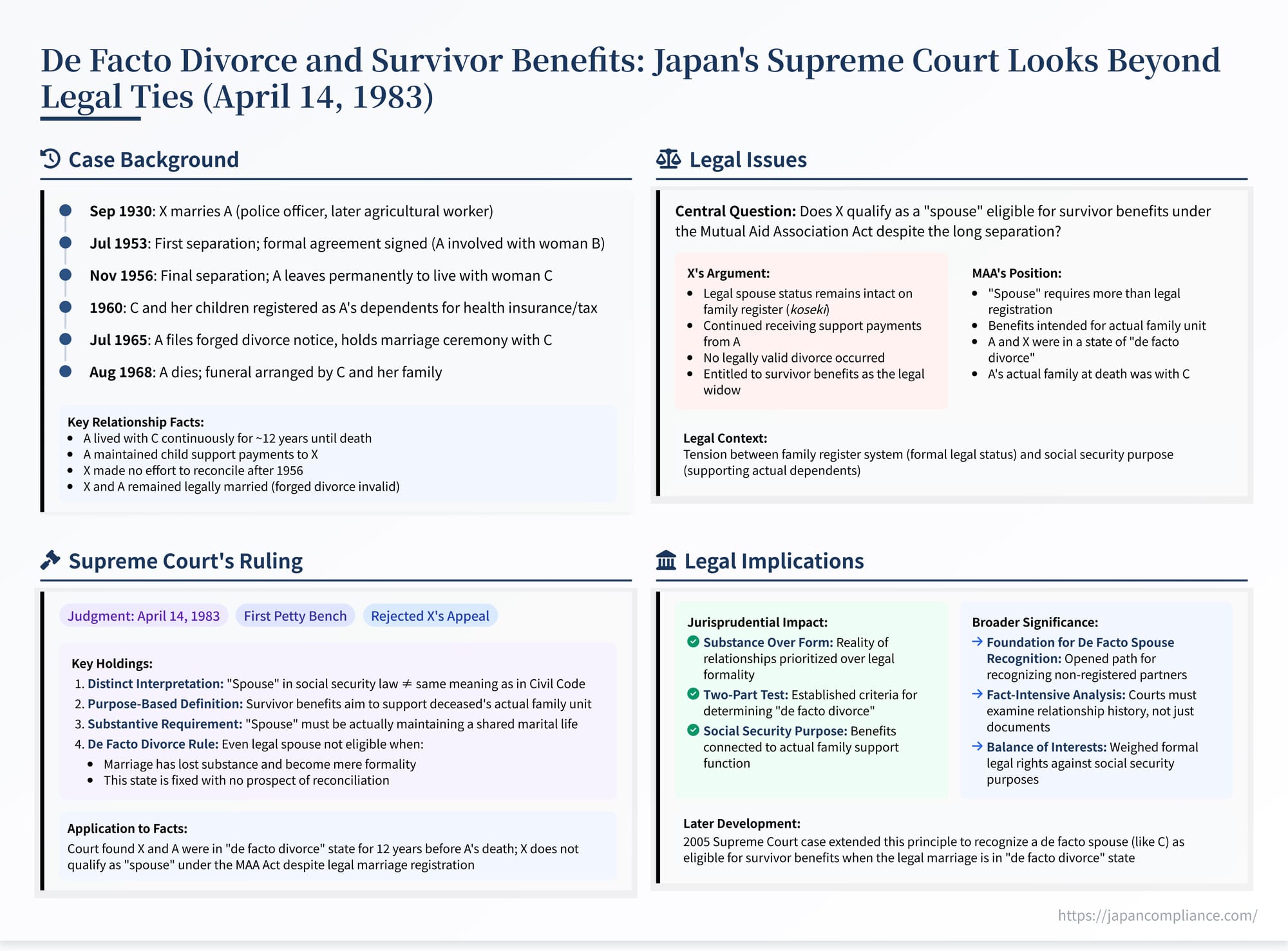

In 1983 the Supreme Court of Japan denied survivor benefits to a legally married but long‑separated spouse, holding that “spouse” in social‑security statutes requires a living marital relationship. The ruling introduced the “de facto divorce” doctrine, prioritising substance over legal form when assessing pension eligibility.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Long and Broken Marriage

- The Legal Framework and Dispute

- Lower‑Court Decisions: De Facto Divorce Disqualifies

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (April 14 1983)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On April 14, 1983, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment addressing a poignant and legally complex issue: Can a legally married spouse who has been separated from the deceased for years and living in a state of de facto divorce still qualify for survivor benefits under a public mutual aid pension system? (Case No. 1979 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 109, "Survivor Pension Rejection Revocation Case"). The Court concluded that under the specific social security law governing the mutual aid association, the term "spouse" requires more than just a legal registration; it necessitates a substantive marital relationship. Where the legal marriage has become a mere shell, devoid of substance and with no prospect of reconciliation, the legally recognized spouse may be disqualified from receiving survivor benefits intended to support the deceased's actual family unit. This decision established an important principle in Japanese social security law, prioritizing the reality of relationships over pure legal formality in certain contexts.

Factual Background: A Long and Broken Marriage

The case presented a long history of marital breakdown, separation, and the formation of new relationships:

- Initial Marriage and Family: The appellant, X, married A in September 1930. At the time, A was a police officer. They had four children together. A later worked for the Tokyo Agricultural Association.

- First Separation: Around May 1952, A became involved with another woman, B, and began neglecting his family life with X. The marital relationship deteriorated, leading A and X to sign a formal separation agreement on July 13, 1953. This agreement stipulated that A would leave the household, provide child support, assign part of his police pension entitlement to X, and that they would mutually refrain from interfering in each other's lives, although they would remain legally married ("maintain the current status on the family register"). A subsequently left and began living with B.

- Attempted Reconciliation and Continued Estrangement: X initiated divorce mediation proceedings in September 1953, but they ended unsuccessfully in December 1953. Around that time, A returned to live with X and the children. The family moved together to public housing in Fuchu City in August 1954. However, according to the findings, marital intimacy between A and X had already ceased around 1951 (reportedly due to A transmitting an STD to X, after which X refused relations following medical advice) and did not resume. A remained isolated within the family and frequently stayed out overnight.

- Second and Final Separation: Around June 1956, A met another woman, C, who lived in Atami at the time, and formed a close relationship. By November 1956, A decided to leave X permanently. Relatives (A's brother D and X's brother E) attempted to mediate and persuade A to stay, but his decision was firm. A and X exchanged words indicating mutual agreement to separate eventually ("Let's separate someday," "Let's do that"). As there was no prospect of reconciliation, they discussed practicalities for the separation, including A's child support obligations until the youngest child reached 18.

- A's New Life with C: A left the family home in Fuchu City around November 21, 1956. He briefly stayed elsewhere, wrote a document expressing his desire for divorce mediation (citing lack of marital relations, discord, alleged abuse), but then, on November 30, 1956, provided X with a written consent form authorizing her to directly receive his entire police pension from that date until November 1964. He also reaffirmed his promise to send child support until the youngest child turned 18. Soon after, A began cohabiting with C. He lived with C and her children (N and K) continuously from that time until his death on August 4, 1968. During this nearly 12-year period, A never returned to stay overnight at X's home.

- Financial Ties and Formal Changes: Throughout the separation, A fulfilled his promise of sending child support and allowed X to receive his police pension. After A's death, the police pension ceased, but X began receiving a survivor's allowance (扶助料 - fujoryō), equivalent to about three-fifths of the pension amount, which continued at the time of the lawsuit. However, other formal ties were severed: in August 1960, X and her children were removed as dependents from A's health insurance and tax records. In December 1960, C and her children were registered as A's dependents instead.

- A and C as a Family Unit: A and C lived together as a family from around 1957, first in Atami, then moving to Mitaka in 1959 and Tachikawa in 1964. C worked (doing piecework, working as a dispatched helper) to help A meet his financial obligations to X. As noted, C was treated as A's spouse for health insurance and tax purposes. Around February 1964, A took C to his hometown in Fukuroi, Shizuoka Prefecture, and introduced her to his mother and relatives as his "new wife." Furthermore, after A submitted a forged notification of divorce from X in July 1965, A and C went through a formal marriage registration ceremony, and A legally adopted C's children. Upon A's death in 1968, his funeral was arranged by C and her family, and his remains were interred by C.

- X's Lack of Intent to Reconcile: Since the final separation in late 1956, X lived with her children and received financial support from A. However, she made no effort to end A's relationship with C or to restore her own marriage with A to a normal state. Around 1962 or 1963, A's former superior, F, advised X to take A back and reconcile, but X demurred and effectively refused the suggestion.

The Legal Framework and Dispute

After A's death, X applied for survivor benefits from the appellee, Y, the Mutual Aid Association for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Organization Personnel (the "MAA"), under the relevant MAA Act (the version applicable at the time). A had presumably become a member of this association through his later employment. Survivor benefits under such systems are generally intended to provide financial support for the family of a deceased member.

Y rejected X's claim. X appealed to the MAA's internal review board, which upheld the rejection. X then filed suit in court seeking the revocation of Y's decision, asserting her right to benefits as A's legally registered spouse.

The core legal question was the interpretation of "spouse" (配偶者 - haigūsha) as used in Article 24, Paragraph 1 of the governing MAA Act, which defined the scope of eligible survivors. Did it refer strictly to the person legally registered as the spouse on the family register (koseki), or did it imply a requirement for a substantive marital relationship to exist at the time of the member's death?

Lower Court Decisions: De Facto Divorce Disqualifies

Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled against X, finding that her claim was rightly rejected. They concluded that, based on the long separation, the circumstances surrounding it (including the separation agreement and A's formation of a new family unit with C), and X's own lack of intent to reconcile, the marital relationship between X and A, despite remaining legally intact, had become entirely defunct and amounted to a de facto divorce. They reasoned that a spouse in such a situation did not fit the intended profile of a survivor eligible for benefits under the MAA Act. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (April 14, 1983)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated April 14, 1983, affirmed the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X's appeal. The Court laid out its reasoning on the interpretation of "spouse" within the context of social security law:

1. "Spouse" in Social Security Law vs. Civil Code:

The Court first established that the concept of "spouse" under the MAA Act (a social security statute) is not necessarily identical to the concept of "spouse" under the Civil Code. While legal registration is the basis for marriage under the Civil Code, social security laws, given their distinct purposes, may allow for interpretations tailored to their specific social welfare objectives. There is room to interpret "spouse" in the MAA Act in light of its underlying social security philosophy and goals.

2. Purpose of MAA Survivor Benefits:

The Court characterized survivor benefits provided by mutual aid associations like Y as public benefits with a social security nature. These associations are typically formed through compulsory membership of individuals working in the same sector (agriculture, forestry, fisheries) and operate on principles of mutual aid. Survivor benefits are paid upon a member's death with the primary aim of guaranteeing the livelihood of the deceased member's family, thereby promoting family stability and welfare, which in turn contributes to the efficient operation of the associated workplaces.

3. Focus on Substantive Reality ("Living Situation"):

Given this purpose, the Court reasoned that the scope of eligible survivors should be understood based on the actual living situation (seikatsu no jittai) of the member and their family, viewed from a realistic perspective. Eligibility should reflect the substantive relationships and dependencies the benefits are meant to support.

4. Defining "Spouse" for Benefit Eligibility:

Applying this purposive approach, the Court concluded that a "spouse" eligible for survivor benefits under the MAA Act refers to someone who, in relation to the deceased member, was mutually cooperating and actually maintaining a shared life constituting a marital relationship in accordance with social norms (shakai tsūnenjō fūfu to shite no kyōdō seikatsu o genjitsu ni itonande ita mono).

5. The De Facto Divorce Exception:

Building on this definition, the Court articulated the key principle: Even a spouse who is legally registered on the family register may not qualify for survivor benefits if:

- The marital relationship has lost its substance and become a mere formality (jittai o ushinatte keigaika shi); AND

- This state has become fixed and stabilized with no prospect of dissolution (reconciliation) in the near future (sono jōtai ga koteika shite chikai shōrai kaishō sareru mikomi no nai toki);

- In other words, when the parties are in a state of de facto divorce (jijitsujō no rikon jōtai).

Such an individual, the Court held, is no longer the type of spouse intended to receive the support provided by survivor benefits.

6. Affirmation of Factual Findings:

The Supreme Court then reviewed the detailed factual findings of the High Court concerning the relationship between X and A (summarized above). It found that the High Court's conclusion – that the marriage was indeed in a state of de facto divorce by the time of A's death, having lost its substance and become permanently fixed – was justified and supported by the evidence presented. The Court found no errors in the lower court's fact-finding process or its legal evaluation of those facts.

Conclusion on X's Eligibility: Based on the finding that X and A were in a state of de facto divorce, the Supreme Court concluded that X did not fall within the definition of a "spouse" eligible for survivor benefits under Article 24, Paragraph 1 of the MAA Act. Therefore, the lower court's judgment upholding the MAA's denial of benefits was correct.

Implications and Significance

This 1983 Supreme Court decision was groundbreaking in formally recognizing the concept of "de facto divorce" within the context of Japanese social security law and allowing it to override formal legal marital status for survivor benefit eligibility.

- Substance Over Form: The ruling established a significant precedent prioritizing the substantive reality of a marital relationship over its legal form when determining eligibility for survivor benefits under public pension/mutual aid systems designed for family support.

- Defining the Eligible "Spouse": It clarified that the purpose of survivor benefits requires the recipient spouse to have been part of an actual functioning marital community life with the deceased member near the time of death. A long-term separation where the marriage has become an empty shell does not meet this requirement.

- The "De Facto Divorce" Doctrine in Social Security: This case effectively introduced the "de facto divorce" doctrine into this area of law. While formal divorce terminates legal rights, this doctrine recognizes that a marriage can cease to function meaningfully long before legal dissolution, and social security benefits tied to the functioning family unit may cease to apply even while the legal marriage persists.

- Implications for "Heavyamous De Facto Marriages": While this case focused on disqualifying the legal spouse, the principle laid the groundwork for later developments. By holding that a defunct legal marriage does not necessarily entitle the legal spouse to benefits, it opened the door for considering the eligibility of a de facto spouse who was living with the deceased in a marital-like relationship (as C was with A in this case). Subsequent case law (notably a 2005 Supreme Court decision) has indeed confirmed that if the legal marriage is deemed to be in a state of de facto divorce, a long-term de facto spouse may be recognized as the eligible "spouse" for survivor pension purposes.

- Fact-Intensive Inquiry: Determining whether a "de facto divorce" exists requires a careful, fact-intensive inquiry into the history of the relationship, including the reasons for and duration of separation, the existence of any intent or effort to reconcile, the nature of ongoing economic ties (distinguishing support based on marital obligation from divorce-like settlements), and the formation of new, stable family units by either party.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 14, 1983, judgment established that under Japan's public mutual aid survivor benefit schemes, eligibility for a "spouse" requires more than just legal marital status. When a marriage has, in reality, completely broken down, lost all substance, and become permanently defunct with no prospect of reconciliation – constituting a "de facto divorce" – the legally recognized spouse may be disqualified from receiving survivor benefits. This ruling emphasizes the social security purpose of such benefits, focusing on supporting the individuals who actually formed the functioning family unit with the deceased member, thereby looking beyond legal formalities to the substantive reality of the relationship.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Overview of the Japanese Pension System — Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Supreme Court of Japan — English Top Page