Dating Scams in Japan: When a Void Sale Poisons the Credit Agreement – A Tale of Two Court Cases

Judgment Dates: October 25, 2011 (Supreme Court) and October 30, 2014 (Tokyo District Court)

"Dating scams," known in Japan as デート商法 (dēto shōhō) or 恋人商法 (koibito shōhō), are a predatory sales tactic where a salesperson feigns romantic interest in a target to build trust and emotional dependency, ultimately manipulating them into purchasing expensive goods or services. When the underlying sales contract in such a scam is deemed void as being against public policy, a critical question arises: what is the legal fate of the credit or loan agreement used to finance the purchase? Two notable Japanese court cases, one reaching the Supreme Court, shed light on this complex interaction between void sales and linked financing agreements.

Understanding "Dating Scams" and Their Collision with Public Policy

Dating scams typically involve a salesperson (often instructed by their company) approaching a target, initiating communication that mimics the development of a romantic relationship. Over time, by expressing affection, creating a sense of exclusivity, and sometimes isolating the target, the salesperson cultivates an emotional vulnerability. Once this emotional leverage is established, the salesperson introduces a product or service – frequently high-priced items like jewelry, art, or investment schemes – and pressures the target into making a purchase, often implying that the continuation of the "relationship" hinges on the sale.

Such sales contracts are often challenged in court as being void under Article 90 of the Japanese Civil Code, which nullifies legal acts that are contrary to "public policy and good morals" (公序良俗違反 - kōjo ryōzoku ihan). The manipulative and exploitative nature of dating scams, which prey on an individual's emotions and impair their rational judgment, frequently leads courts to find the resulting sales contracts void. These can be seen as a type of "exploitative transaction" (暴利行為 - bōri kōi), where a gross imbalance in the value exchanged is coupled with the exploitation of the consumer's vulnerability, ignorance, or distress.

It's worth noting that Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA) was later revised (in 2018) to specifically address dating scams, adding a provision (Article 4, Paragraph 3, Item 4) that allows consumers to cancel contracts concluded under such manipulative circumstances, provided certain conditions are met. However, the cases discussed here were adjudicated before or without primary reliance on this specific amendment, focusing instead on general public policy principles and existing consumer protection laws.

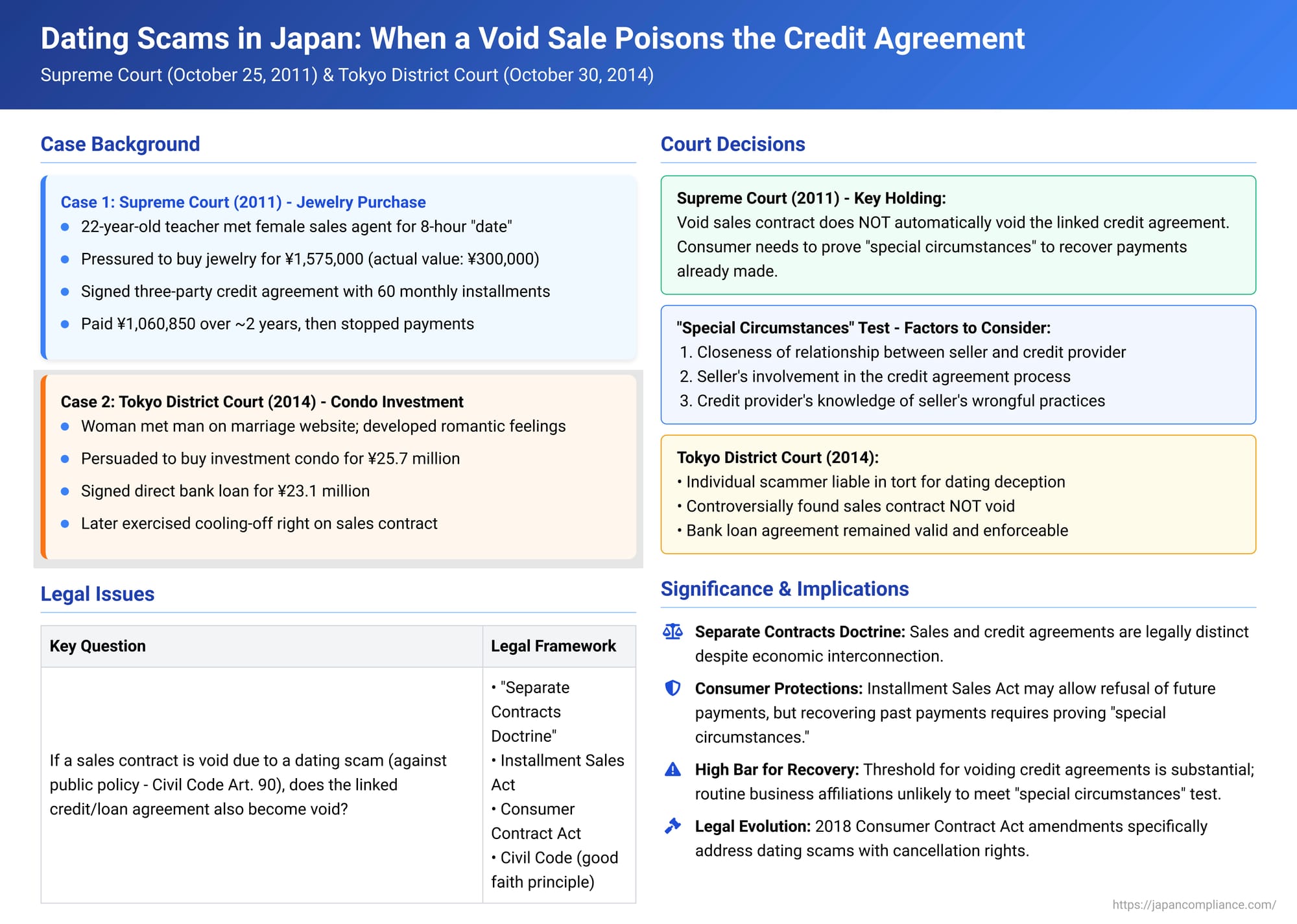

Case Study ①: The Overpriced Jewelry and Three-Party Credit (Supreme Court, October 25, 2011)

This case (Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 1096) involved a young man, X, and his unfortunate entanglement in a dating scam leading to the purchase of jewelry financed through a three-party credit agreement.

- The Scam: X, a 22-year-old who had recently secured a teaching position, was contacted by Company A, a jewelry seller. On March 29, 2003, he met with C, a 21-year-old female salesperson from Company A, at a family restaurant. Over an exhausting eight-hour period, C described jewelry items while engaging in affectionate behavior, such as holding X's hand and cuddling up to him. During this time, other colleagues of C joined them. Eventually, another individual, D, described as wearing sunglasses and a black suit, appeared and aggressively pressured X to make a purchase. X expressed his unwillingness but felt intimidated and unable to leave. He was told the items were a good value as they were handcrafted by foreign artisans. Ultimately, X agreed to purchase three jewelry items for a total price of ¥1,575,000. A later appraisal revealed the items were non-brand and collectively worth only around ¥300,000.

- The Financing: To pay for the jewelry, X signed a credit agreement application presented by C. This was a three-party credit agreement (立替払契約 - tatekaebarai keiyaku, an installment payment agreement where the creditor pays the seller and the consumer repays the creditor). Company B was the original credit provider. Under the terms, B would pay Company A the purchase price, and X would repay B a total of ¥2,189,250 in 60 monthly installments (this sum included ¥614,250 in interest and fees). X made payments from May 2003 to September 2005, totaling ¥1,060,850, but then ceased payments. Company B later assigned its credit business to Y, who became the defendant in X's lawsuit.

- Lower Courts' Divergence: X sued Y, seeking (among other things) the return of payments already made, arguing the credit agreement was void because the underlying sales contract with Company A was void against public policy due to the dating scam. The first instance court dismissed X's claims. However, the Nagoya High Court found in X's favor. It declared the sales contract void against public policy and, significantly, ruled that this voidness caused the credit agreement to "lose its purpose and become ineffective." The High Court allowed X not only to refuse further payments but also to recover the payments already made to the credit company. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

- Supreme Court's Ruling on the Credit Agreement:

The Supreme Court, while not disturbing the High Court's finding that the sales contract was void against public policy (as this specific point wasn't appealed by the relevant party, Company A, which was not directly involved in this appeal between X and Y), reached a different conclusion regarding the credit agreement.The Court reiterated the principle that in a three-party individual installment purchase finance arrangement, the sales contract (between consumer and seller) and the credit agreement (between consumer and credit provider) are legally separate contracts. Even if they are economically and practically closely linked, problems or defects arising in the sales contract (such as its voidness) cannot automatically be asserted by the consumer against the credit provider to invalidate the credit agreement itself or to reclaim payments already made under it.The Court acknowledged that the Installment Sales Act (割賦販売法 - kappu hanbai hō, specifically Article 30-4 of the pre-2008 version) grants consumers the right to assert defenses arising from the sales contract against the credit provider when faced with demands for unpaid installments (a concept known as 抗弁の接続 - kōben no setsuzoku, or connection of defenses). However, this statutory right primarily addresses the refusal of future payments, not the recovery of past payments.For the credit agreement itself to be deemed void (which would then allow the consumer to reclaim payments already made to the credit provider as unjust enrichment), the Supreme Court stated that "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) must exist. These special circumstances would need to be such that it would be contrary to the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku) to hold the consumer to the terms of the credit agreement. The Court outlined factors to consider in determining if such special circumstances exist:

* (a) The relationship between the seller and the credit provider: (e.g., close capital ties, exclusive dealing).

* (b) The extent and nature of the seller's involvement in the credit agreement conclusion process: (e.g., did the seller act as a mere conduit, or did the credit provider independently assess the consumer?).

* (c) The credit provider's awareness (or constructive knowledge) of the seller's wrongful acts or the illicit nature of the sale.Applying these factors to X's case, the Supreme Court found no such "special circumstances":Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the voidness of the sales contract with Company A did not, in this instance, lead to the voidness of the separate credit agreement with Company B (and by extension, Y). Consequently, X could not recover the payments already made to the credit company under the theory that the credit agreement was void. (X's alternative claim to cancel the credit agreement under the Consumer Contract Act was also found by the Supreme Court to be time-barred due to X's failure to exercise the cancellation right within the statutory period after he could have recognized the grounds for cancellation). The part of Y's appeal concerning unpaid installments was dismissed because Y failed to submit the required reasons for appeal on that point, effectively leaving the High Court's decision (allowing X to refuse further payments based on the void sale) undisturbed for those unpaid amounts.- Company A was merely one of many affiliated merchants of Company B; there was no evidence of an unusually close or problematic relationship.

- Company B did not entirely delegate the credit application process to Company A. B's staff had directly telephoned X to confirm his intention to enter the credit agreement and its terms, during which X raised no objections.

- X had made payments under the credit agreement for a considerable period (over two years) without protest.

- There was no evidence that Company B, prior to concluding the credit agreement with X, had received complaints about Company A's sales practices from other consumers or had been alerted to issues with Company A by consumer protection agencies.

Case Study ②: The Condo Investment Scam and a Direct Bank Loan (Tokyo District Court, October 30, 2014)

This case (Heisei 25 (Wa) No. 13712) involved a female plaintiff, X, who was ensnared in a dating scam leading to the purchase of an investment condominium, financed by a direct loan from a bank.

- The Scam: In October 2012, X registered on a marriage introduction website. She was contacted by Y2, a male member of the site. They began communicating via email and phone, eventually meeting in person in early December 2012 and having meals together. On December 15, Y2 introduced X to the idea of investing in a condominium. X, who had developed romantic feelings for Y2 and wished to maintain their connection, complied with Y2's requests to provide personal documents like pay slips and her driver's license. On December 24, X accompanied Y2 to a coffee shop where they met with employees of Company A, a real estate firm. X was presented with a sales contract for a condominium priced at ¥25.7 million, told that an agreement had been reached, and was urged to sign various documents, including the sales contract and a sublease agreement. She paid Company A ¥100,000 in cash as a deposit.

- The Financing: Immediately after signing the sales documents, X was taken to a branch of Y1 Bank, located in the same building. There, she signed a loan agreement (金銭消費貸借契約 - kinsen shōhi taishaku keiyaku) with Y1 Bank for the remaining ¥23.1 million of the purchase price.

- X's Subsequent Actions: On December 31, X exercised her cooling-off right under the Real Estate Brokerage Act to cancel the sales contract with Company A; this cancellation was accepted. Later, on February 12, 2013, X notified Y1 Bank of her intention to cancel the loan agreement under the Consumer Contract Act.

- X's Lawsuit: X sued Y2 for tort damages (solatium) due to the emotional distress caused by his deceptive conduct leading to the sales contract. She also sued Y1 Bank, primarily seeking a confirmation that she had no outstanding debt under the loan agreement (arguing for its cancellation under the CCA or its voidness against public policy) and, preliminarily, for tort damages against the bank for an alleged breach of its duty of explanation under the principle of good faith.

- Tokyo District Court's Rulings:

- Liability of Y2 (the individual scammer): The Court found Y2 liable in tort. It determined that Y2 had, from the outset, intended to solicit X for the purchase of a condominium of questionable investment value by feigning romantic interest. Y2 exploited X's hopes for a relationship and deprived her of the opportunity to make a calm, rational judgment. This conduct was deemed a serious breach of the principle of good faith, warranting an award of solatium to X.

- Validity of the Sales Contract with Company A: In a somewhat controversial finding, the Court, while acknowledging Y2's tortious solicitation methods, held that X had sufficiently understood the contents of the sales contract when she signed it. Therefore, the Court concluded that the sales contract itself was not void against public policy. (Legal commentary has criticized this aspect, suggesting it might implicitly condone the results of illegal solicitation if the consumer formally understands the terms despite the manipulation).

- Liability of Y1 Bank: Consequently, X's claims against Y1 Bank for the nullification of the loan agreement or for damages were dismissed. The judgment implies that since the primary sales contract was not found to be void, and in the absence of any specific wrongdoing directly attributable to the bank itself or the kind of "special circumstances" that would closely tie the bank to the seller's misconduct (as discussed in the Supreme Court's Case ① framework), the loan agreement remained valid and enforceable.

Analyzing the Courts' Approach to Linked Financing in Dating Scams

These two cases, particularly the Supreme Court's decision in Case ①, illustrate the prevailing judicial approach in Japan to the "domino effect" of a void sales contract on related financing agreements:

- The "Separate Contracts" Doctrine (別契約論 - bekkeiyaku ron): The judiciary, led by the Supreme Court, generally maintains that a sales contract between a consumer and a seller, and a financing agreement (be it a three-party credit plan or a two-party loan) between the consumer and a financial institution, are legally distinct and separate contracts. This holds even if they are economically intertwined and concluded as part of a single overall transaction from the consumer's perspective.

- Voidness of Sale Does Not Automatically Void Financing: As a consequence of the separate contracts doctrine, the fact that a sales contract is void (e.g., for being against public policy due to a dating scam) does not, in itself, automatically render the related financing agreement void.

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception for Voiding Financing: For a consumer to successfully argue that the financing agreement is also void (and thus be entitled to recover payments already made to the financier), they must demonstrate the existence of "special circumstances." These circumstances must be compelling enough to make it contrary to the principle of good faith and fair dealing to enforce the financing agreement. As outlined by the Supreme Court in Case ①, this involves scrutinizing:

- The nature and closeness of the relationship between the seller and the financier.

- The degree of the seller's involvement in facilitating the financing agreement.

- The financier's knowledge (actual or constructive) of the seller's illegal or unconscionable practices.

The threshold for establishing these "special circumstances" appears to be quite high. Routine business affiliations or standard procedures where the financier independently confirms the consumer's intent are unlikely to meet this bar.

- Statutory Defenses for Unpaid Installments (Installment Sales Act): Consumers often have a statutory right under the Installment Sales Act to raise defenses against the financier that they could have raised against the seller, but this primarily applies to refusing payment of outstanding installments. It generally does not, without more, provide a basis for reclaiming payments already made, unless the financing contract itself is found to be void or specific provisions of the current (post-2008 reforms) Installment Sales Act concerning refunds in cases like cooling-off or certain types of mis-selling apply.

Criticism and the Path Forward

The "separate contracts" doctrine and the high bar for "special circumstances" have been subjects of considerable academic discussion and criticism. Many legal scholars argue for a more integrated approach that recognizes the functional unity of these transactions from the consumer's standpoint. They contend that the current doctrine can place a disproportionate risk of seller misconduct on the consumer, especially when a third-party financier, who often has a close and ongoing relationship with the seller and benefits from the overall sales system, is insulated from the fallout of the seller's wrongdoing. Theories proposing joint enterprise liability or heightened duties of care and investigation for financial institutions that regularly finance sales for particular merchants are often advocated as means to enhance consumer protection.

The evolution of consumer law, including the 2018 amendments to the Consumer Contract Act specifically targeting dating scams with cancellation rights and clarifying rules for the return of payments upon cancellation, reflects an ongoing effort to address these challenges. However, the fundamental tension between the legal separateness of contracts and the economic reality of interconnected transactions in consumer finance remains a key area of legal development.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's decision in the 2011 jewelry dating scam case clarifies that while a sales contract procured through such manipulative tactics may be void against public policy, the associated credit agreement is not automatically nullified. Consumers seeking to invalidate the credit agreement and recover payments already made must prove "special circumstances" that demonstrate a sufficiently close link or culpability on the part of the credit provider concerning the seller's illicit practices. While consumers may generally refuse to pay outstanding installments to the creditor if the underlying sale is void (due to statutory connected defense rights), reclaiming past payments from the financier remains a significant hurdle unless the financing agreement itself can be directly impugned or newer specific statutory refund rights apply. These cases highlight the critical importance for consumers to be wary of high-pressure sales tactics, especially those intertwined with emotional manipulation, and underscore the ongoing legal dialogue about how best to allocate risks and protect consumers in complex, multi-party transactions.