Data Privacy in Japan’s DX Era: Balancing Utilization & Protection

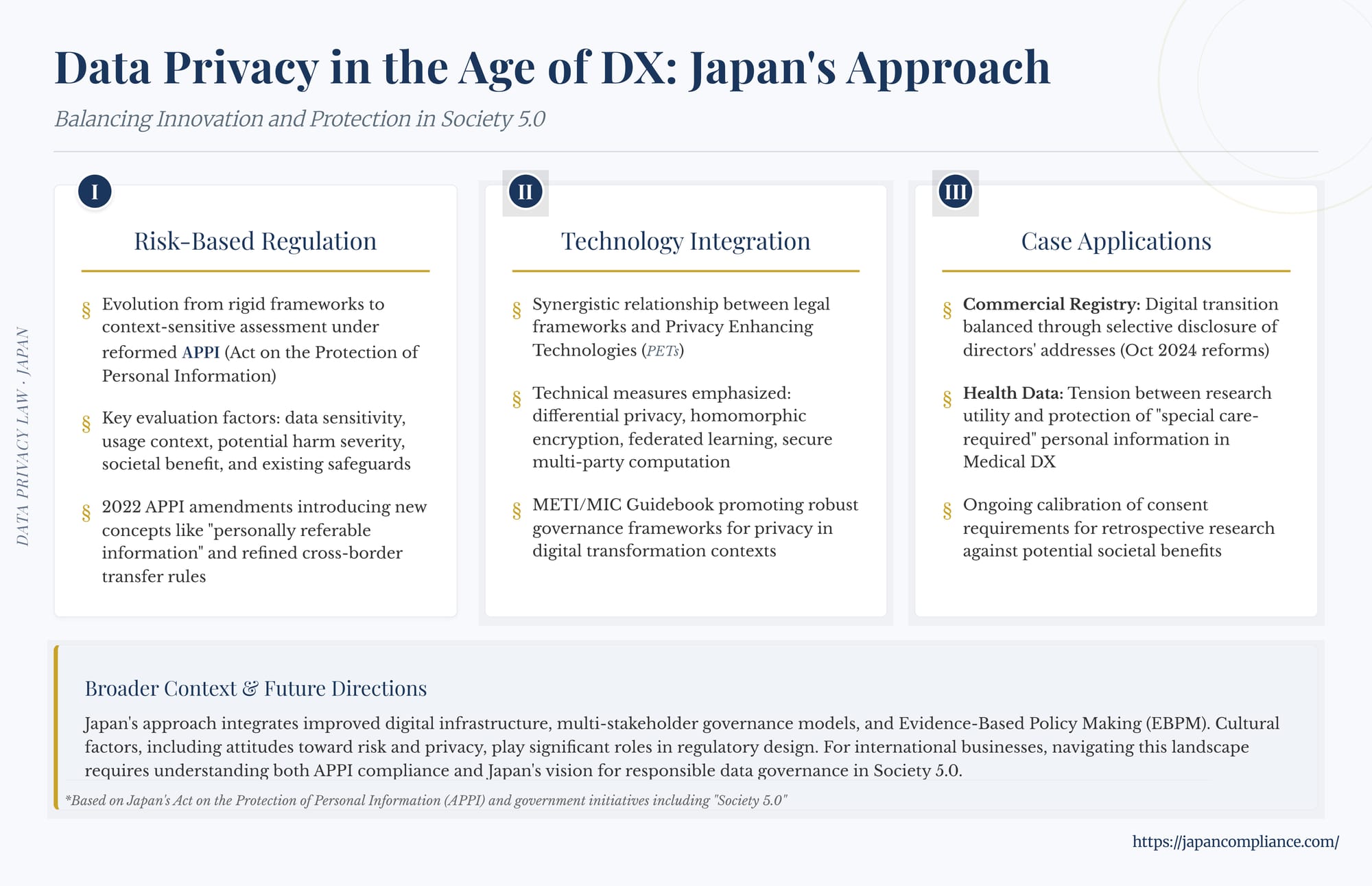

TL;DR: Japan is pivoting to a risk-based data-privacy model under the APPI while pushing Digital Transformation (DX) and Society 5.0. Businesses must weigh data-driven innovation against heightened duties on consent, cross-border transfers, and sensitive-data safeguards—and monitor new rules on AI training and personally referable information.

Table of Contents

- The Core Tension: Innovation Fuel vs. Individual Rights

- Japan’s Evolving Risk-Based Regulatory Philosophy

- Integrating Technology and Law

- Case Study 1: Digitising the Commercial Registry

- Case Study 2: Healthcare Data and Research

- Broader Context: Infrastructure, Governance, Culture

- Conclusion: Practical Takeaways

Digital Transformation (DX) is reshaping industries worldwide, promising unprecedented efficiency, innovation, and personalized services through the power of data. Japan, actively promoting its "Society 5.0" vision for a data-driven future, is deeply engaged in harnessing DX's potential. However, this transformation fundamentally challenges existing paradigms of data privacy. As businesses collect, analyze, and share vast amounts of information, particularly personal data, navigating the evolving legal and ethical landscape is paramount. Japan's approach, underpinned by its Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) and influenced by ongoing governmental reviews, reflects a concerted effort to balance the immense benefits of data utilization with the critical need for robust privacy protection. Understanding this dynamic approach is essential for any organization operating within Japan's digital economy.

The Core Tension: Innovation Fuel vs. Individual Rights

At the heart of the DX and privacy debate lies an inherent tension. On one hand, data is the fuel for innovation. Analyzing large datasets enables businesses to optimize operations, develop new services, conduct vital research (especially in areas like healthcare), and offer highly personalized customer experiences. DX initiatives often depend on the seamless flow and linkage of diverse data sources.

On the other hand, the increased collection and use of personal data amplify privacy risks. Unauthorized access, misuse, discrimination based on data profiles, and the chilling effect of pervasive surveillance are legitimate concerns. Traditional privacy frameworks, often developed in an analog era, may struggle to adequately address the speed, scale, and complexity of data processing in the digital age.

Japanese legal and policy discussions often frame privacy protection not just as an individual right but as a crucial preventative mechanism. The goal is to mitigate the risk of potential harm before it materializes by establishing rules around data collection, handling, and use. This preventative perspective shapes how Japan is approaching the re-evaluation of privacy norms in the face of DX.

Japan's Evolving Regulatory Philosophy: Towards a Risk-Based Approach

Recognizing that rigid, one-size-fits-all privacy rules could stifle beneficial DX initiatives, Japan is increasingly moving towards a more nuanced, risk-based approach to data protection regulation. This shift has been evident in recent governmental deliberations and updates to guidelines surrounding the APPI. Instead of relying solely on abstract principles or strict compliance checklists, this approach emphasizes evaluating privacy risks in context.

Several key factors are considered in this rebalancing act:

- Data Sensitivity: Information requiring special care (e.g., health data, race, beliefs) necessitates stricter safeguards than less sensitive data. The APPI specifically defines "special care-required personal information."

- Context of Use: The purpose of data processing significantly influences risk. Using data for beneficial medical research under strict controls presents different risks than using it for opaque targeted advertising.

- Likelihood and Severity of Harm: Regulators assess the realistic probability of misuse and the potential impact on individuals if privacy is compromised.

- Public Interest vs. Private Harm: The societal benefits derived from data utilization (e.g., public health, efficient administration) are weighed against potential individual privacy intrusions.

- Existing Safeguards: The presence of technical security measures, organizational policies, ethical oversight, and legal accountability mechanisms influences the overall risk assessment.

This risk-based philosophy acknowledges that not all data processing activities carry the same level of risk and allows for more tailored regulatory responses. It encourages organizations to proactively assess and mitigate risks specific to their data handling practices, rather than merely adhering to formalistic rules. Recent amendments to the APPI (effective April 2022) reflect this, introducing concepts like "personally referable information" and refining rules around consent and cross-border transfers, demanding a more context-aware approach from businesses. Furthermore, ongoing discussions for potential future APPI amendments consider measures like administrative fines and enhanced collective redress mechanisms, suggesting a continued focus on effective enforcement based on risk and impact.

Integrating Technology and Law

A crucial aspect of Japan's modern approach is the recognition that legal rules alone are insufficient. Effectively protecting privacy in the DX era requires integrating legal frameworks with technical solutions. There's growing interest in:

- Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs): Techniques like differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, federated learning, and secure multi-party computation allow data analysis and collaboration while minimizing the disclosure of raw personal information. While global adoption faces challenges related to standardization, complexity, and demonstrating regulatory compliance, PETs are seen as potentially valuable tools.

- Robust Security Measures: Encryption, access controls, anonymization, and pseudonymization techniques are fundamental requirements under the APPI. Government guidance emphasizes implementing appropriate security standards, particularly when using third-party services like cloud platforms.

- Data Governance Frameworks: Internal organizational policies, data mapping, impact assessments, and designated privacy officers are essential for managing data responsibly. Guidelines, such as the "Guidebook on Corporate Governance for Privacy in Digital Transformation (DX)" jointly formulated by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), encourage businesses to embed privacy considerations into their governance structures.

The idea is not to replace law with technology, but to use them synergistically. Technology can help implement legal principles effectively (e.g., minimizing data exposure), while law provides the necessary framework, accountability, and redress mechanisms.

Case Study 1: Digitizing the Commercial Registry

A pertinent example of this rebalancing act involves Japan's commercial registry. Traditionally, accessing company information, including the names and home addresses of representative directors, required physical visits to registry offices. DX initiatives aimed to make this information accessible online for greater transparency and efficiency, aiding processes like legal discovery, service of process in litigation, and due diligence.

However, putting directors' home addresses online presented significantly amplified privacy risks compared to the analog system. The ease of digital access and replication raised serious concerns about potential misuse for stalking, harassment, or other illicit purposes. These risks were highlighted as being particularly acute for certain groups, such as female entrepreneurs, who might face disproportionate threats.

This led to considerable debate and policy adjustments. While the benefit of transparency for legal accountability was acknowledged, the heightened privacy risks in the digital context necessitated a re-evaluation. Consequently, measures were implemented in October 2024 allowing representative directors, upon application and meeting certain criteria (such as demonstrating a risk of harm), to have the specific street address portion of their registered home address withheld from publicly available certificates and online services. This represents a practical compromise, attempting to preserve the necessary function of the registry while mitigating the most severe privacy risks amplified by digitization. It illustrates the move away from simply replicating analog rules online towards a more risk-sensitive digital governance approach.

Case Study 2: Balancing Health Data Utility and Privacy

The healthcare sector is another critical area where the tension between data utilization and privacy is prominent. Japan, facing an aging population and rising healthcare costs, sees enormous potential in using health data (including electronic health records and genomic information) for medical research, personalized medicine, and improving public health outcomes. Government initiatives actively promote "Medical DX" and the establishment of platforms for secure data linkage and utilization.

However, health information is among the most sensitive categories of personal data, classified as "special care-required personal information" under the APPI. Its use raises significant privacy concerns. While utilizing aggregated or anonymized data poses fewer issues, research often benefits from access to detailed, individual-level data.

The regulatory challenge lies in facilitating beneficial research while preventing misuse or discrimination. The APPI generally requires explicit consent for handling sensitive data and for providing personal data to third parties (including researchers in many cases). The 2022 APPI amendments, in some interpretations, have been seen as potentially restricting certain types of retrospective research using existing patient records without specific, renewed consent for each research project, creating hurdles for researchers.

The debate involves weighing the potential societal benefits of health research against the privacy rights of individuals. Proponents of greater data access argue that when data is handled by reputable research institutions under strict ethical guidelines and robust security protocols, the actual risk of harm to individuals (e.g., discriminatory treatment based on disclosed health status) is often low compared to the potential benefits of medical breakthroughs. This aligns with the risk-based approach: evaluating the necessity of strict consent requirements based on the actual, contextual risk of harm versus the opportunity cost of hindering potentially life-saving research. Finding the right balance – potentially through mechanisms like secure research environments, advanced anonymization techniques (potentially leveraging PETs), and clear governance frameworks for data access – remains an ongoing challenge central to Japan's data strategy.

Broader Context: Infrastructure, Governance, and Culture

Effectively managing data privacy and utilization in the DX era also depends on broader factors:

- Digital Infrastructure: Japan is working to improve its underlying digital infrastructure, including establishing reliable base registries for corporations and potentially real estate, and promoting secure digital identities (like the GbizID for businesses). Consistent, reliable, and linkable foundational data is crucial for enabling DX efficiently and securely, though challenges related to legacy systems and data inconsistencies persist.

- Governance Models: The complexity of DX requires collaborative governance. Expert discussions in Japan have highlighted the need for multi-stakeholder approaches, bringing together government agencies, industry players, academic experts, and civil society representatives to co-design rules and best practices. Concepts like "Agile Governance," which emphasize iterative, flexible, and data-informed regulation, are being explored to keep pace with technological change.

- Evidence-Based Policymaking (EBPM): There is a growing push within the Japanese government, formalized since the mid-2010s, to adopt EBPM principles. This involves using objective data and evidence to design policies, monitor their effectiveness, and make necessary adjustments. In the context of data privacy and DX, EBPM means assessing the real-world impact of regulations, ensuring they achieve their intended goals without imposing unnecessary burdens or stifling innovation. Challenges remain in fully implementing EBPM, often related to data availability and analytical capacity within government.

- Cultural Factors: Societal attitudes towards risk and privacy also play a role. Some analyses suggest a tendency towards a "zero-risk" mentality in Japan, which can sometimes lead to overly cautious regulations that hinder beneficial data use. Furthermore, ensuring that regulatory design considers diverse perspectives and potential disparate impacts (e.g., the privacy risks faced by female entrepreneurs) is crucial for creating truly inclusive and equitable digital systems.

Conclusion: Navigating the Dynamics

Japan's journey into the age of DX involves a continuous effort to adapt its data privacy framework. The approach is characterized by a shift towards risk-based assessment, recognizing that context matters and that different data uses entail different levels of risk. There is a clear move to integrate legal rules with technological solutions, leveraging tools like PETs and robust security alongside updated regulations like the APPI.

Crucially, the process involves rebalancing – weighing the benefits of data utilization against privacy risks, considering public interest, individual rights, and societal values. Case studies like the digitalization of the commercial registry and the evolving policies around health data illustrate this ongoing calibration.

For international businesses, understanding this dynamic landscape is key. It requires not only compliance with the letter of the law (APPI) but also an appreciation of the underlying principles: risk assessment, the importance of technical safeguards, the specific sensitivities around certain data types (like health information), and the broader push towards responsible data governance within Japan's Society 5.0 vision. Engaging with Japan's digital economy necessitates a proactive, context-aware, and technologically informed approach to data protection.

- Privacy in Japan: Navigating Tort Law and Data Protection for US Companies

- Data Privacy in Japanese Criminal Investigations: A Guide for US Multinationals

- Bridging the Atlantic Again? Understanding the EU-US Data Privacy Framework

- Personal Information Protection Commission — APPI Q&A (English)

https://www.ppc.go.jp/en/legal/decisions/faq/