Data Portability & Antitrust: Lessons from Japan’s Crackdown on Restrictive Transfer Terms

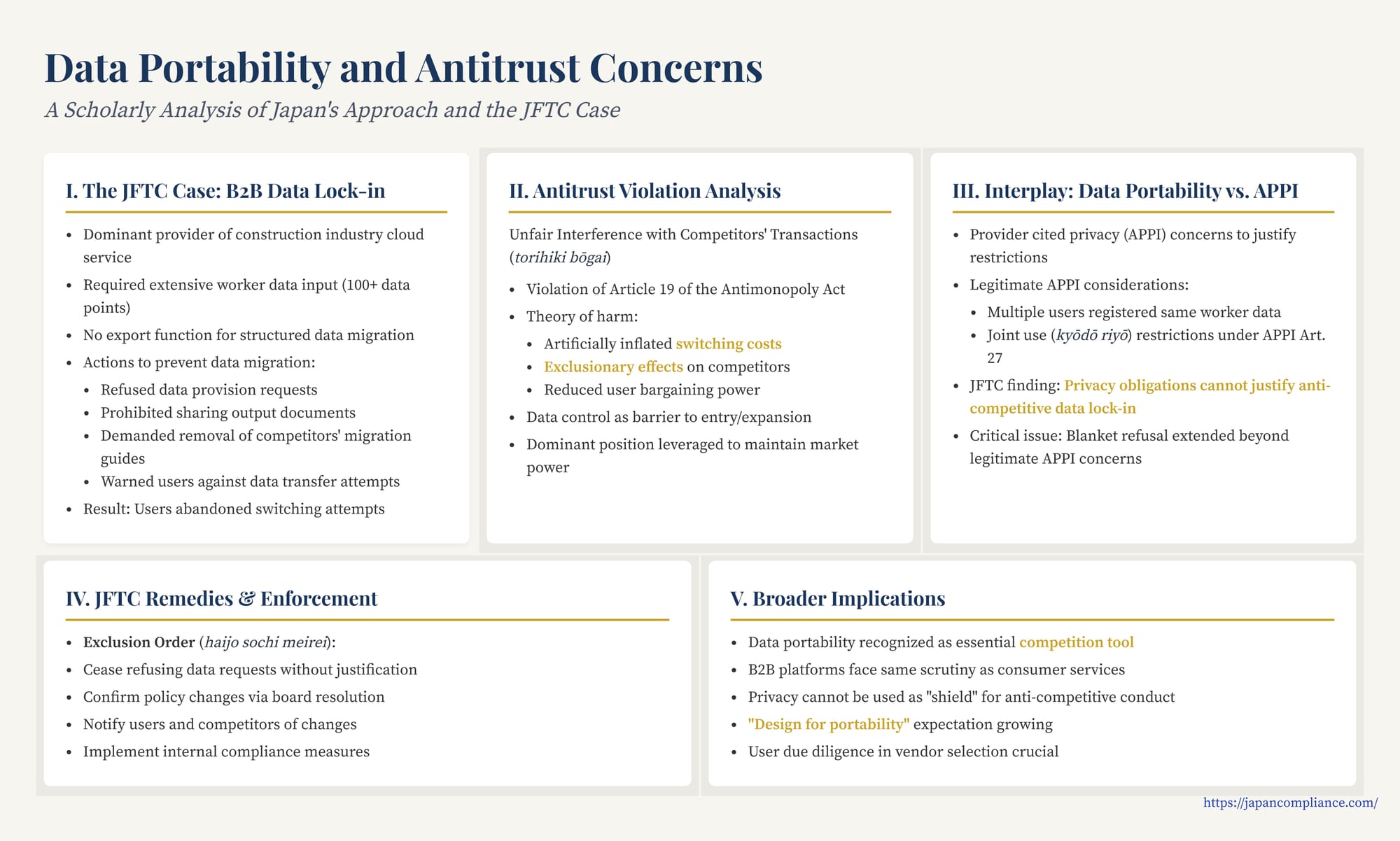

TL;DR: The JFTC’s 2024 exclusion order shows that blocking data portability—even citing privacy risks—can breach Japan’s Antimonopoly Act. Dominant platforms must enable users to export their own data while still complying with APPI.

Table of Contents

- JFTC Case: Data Lock-in in a Specialized B2B Cloud Service

- Antitrust Violation: Interference with Transactions

- The Interplay: Data Portability vs. Data Protection (APPI)

- JFTC Remedies and Enforcement Approach

- Broader Implications and International Context

- Conclusion: Data Flow and Fair Competition in Japan

In today's digital economy, data is often described as the new oil – a critical asset enabling innovation, efficiency, and competitive advantage. However, control over data can also become a significant source of market power, potentially leading to anti-competitive practices. One such practice gaining increasing attention from regulators worldwide, including in Japan, involves dominant platform providers restricting the ability of their users to transfer their data to competing services. This "data lock-in" can create high switching costs, stifle competition, and ultimately harm users.

A recent enforcement action by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) highlights the antitrust risks associated with impeding data portability, even in the complex B2B cloud services sector and amidst legitimate data protection considerations. This case offers valuable lessons for businesses operating in Japan, both as service providers and users, on the interplay between data control, competition law, and data privacy regulations.

The JFTC Case: Data Lock-in in a Specialized B2B Cloud Service

In December 2024, the JFTC issued an exclusion order (haijo sochi meirei) against a dominant provider (referred to here as "Provider A") of a specialized cloud-based service ("Service A"). Service A facilitates the management of legally mandated labor and safety documentation within the construction industry. Its users include both main contractors and numerous subcontractors who rely on the platform to exchange critical compliance information.

A key feature of Service A was the requirement for users to input extensive and detailed information about individual construction workers (potentially over 100 data points per worker). This data, essential for generating the required safety documents, represented a significant investment of time and resources for the user companies. While users could output formatted compliance documents (chōhyō) from the system, Provider A did not offer a function to easily export the underlying raw worker data in a structured, machine-readable format suitable for migration to a different platform.

As competitors ("Service B" and "Service C") emerged offering alternative labor/safety management platforms, users wishing to switch faced the daunting task of manually re-inputting vast amounts of worker data into the new system. Recognizing this friction, competitors sought ways to facilitate data migration. Service B, for example, published online guidance suggesting users could potentially extract data by providing the formatted documents (chōhyō) generated by Service A to Service B for processing.

The JFTC investigated allegations that Provider A took several steps, ostensibly to protect its market position, that actively hindered users' ability to switch and impeded competitors:

- Refusal of Data Provision: Provider A allegedly refused requests from its users to provide their own registered worker data in a transferable format, often citing privacy protection concerns under Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), but reportedly without sufficient justification in cases where the request pertained to the user's own data inputs.

- Restrictive Terms of Service: Provider A revised its user agreement to explicitly prohibit users from providing the outputted formatted documents (chōhyō) to third-party services. It also broadly forbade processing the worker data held within the system for purposes outside the defined scope of "joint use" (kyōdō riyō) under the APPI, effectively blocking data migration efforts.

- Pressure on Competitors: Provider A allegedly contacted Service B, demanding the removal of its online data migration guide, claiming it encouraged users to violate the newly revised terms of service.

- User Warnings: When Provider A became aware that some users were providing the outputted documents to Service C to facilitate switching, it allegedly posted notices on its service portal and sent emails to users, warning that such actions violated the terms of service.

According to the JFTC's findings, these actions had tangible anti-competitive effects. Some users reportedly abandoned attempts to switch services due to the difficulties in data transfer. Competitors Service B and Service C faced significant hurdles in acquiring new customers, as potential clients were deterred by the data lock-in. Service B also removed its migration guide, hindering its ability to compete effectively.

Antitrust Violation: Interference with Transactions

Based on this conduct, the JFTC concluded that Provider A had engaged in unfair interference with competitors' transactions (torihiki bōgai). This falls under the category of unfair trade practices prohibited by Article 19 of the Antimonopoly Act (AMA), typically defined further by the JFTC's General Designations (in this case, likely General Designation No. 14).

The theory of harm centers on the artificial inflation of switching costs and the exclusionary effect on competitors:

- Increased Switching Costs: By technically and contractually preventing easy data export, Provider A significantly raised the costs and complexity for users wanting to move to a competing service. This lock-in effect reduces users' bargaining power and insulates the dominant provider from competitive pressure, even if rivals offer superior products or pricing.

- Exclusionary Impact: Data portability is crucial for competition in markets where users invest heavily in platform-specific data. By blocking migration paths, Provider A effectively hindered the ability of Service B and Service C to compete on the merits, denying them the opportunity to onboard customers efficiently. This conduct leverages dominance in the service market to protect that position from competitive challenges.

While perhaps not explicitly framed as an abuse of dominance case in the exclusion order summary, the underlying principle is similar: a dominant firm using its control over essential data or platform functions to impede competition. This aligns with global antitrust scrutiny of dominant digital platforms and ecosystems where data control can function as a significant barrier to entry and expansion for rivals.

The Interplay: Data Portability vs. Data Protection (APPI)

A critical dimension of this case is the interaction between competition law principles favoring data portability and the requirements of data protection law (APPI). Provider A reportedly justified its refusal to provide data and its restrictive terms partly on the grounds of needing to protect the personal information of the workers whose details were registered in the system.

This raises a legitimate point: the worker data is indeed personal information under the APPI. Furthermore, within Service A's ecosystem, data about a specific worker might be registered or updated by multiple different users (e.g., a main contractor and various subcontractors the worker is associated with). Under the APPI, providing one user (User X) with personal data originally entered or controlled by another user (User Y) generally requires the data subject's consent or another valid legal basis, as User X would typically be considered a "third party" relative to User Y's data processing relationship. The concept of "joint use" (kyōdō riyō) under APPI (Art. 27(5)(iii)) allows data sharing among a predefined scope of users for a common purpose without requiring individual consent for each transfer within that scope, but exporting data outside that joint use framework to a competitor typically falls outside this exception.

Therefore, Provider A had a valid legal obligation under the APPI to prevent User X from extracting and transferring personal data belonging to other users (User Y, User Z) without appropriate consent or legal basis. A blanket export function providing User X with all worker data they could view within the system, regardless of its origin, could indeed lead to APPI violations.

However, the JFTC's action suggests that legitimate data protection obligations cannot be used as a pretext for anti-competitive data lock-in. The core issue appears to have been Provider A's blanket refusal and prohibition, which allegedly extended to situations where:

- The user was requesting only the data they themselves had registered.

- The user might have obtained necessary consents from data subjects (workers) for the transfer.

- Technical means could potentially distinguish between data "owned" by the requesting user and data belonging to others within the system.

The JFTC's stance implies that platforms, especially dominant ones, have a responsibility to design their systems and policies in a way that facilitates APPI compliance without unduly restricting a user's ability to access and port their own data or data for which they have a legitimate basis for transfer. Blanket technical barriers or overly broad contractual prohibitions that prevent legitimate data portability, even when justified by citing general privacy risks, can attract antitrust scrutiny if they serve to exclude competitors. Finding technical and policy solutions that enable granular data control and export, aligned with APPI requirements, becomes crucial.

(Note: Provider A reportedly amended its terms of service in July 2024, prior to the JFTC order, to permit data transfers where allowed under APPI, such as with the data subject's consent. The JFTC order reflects this by requiring confirmation that the blanket prohibition is no longer in effect ).

JFTC Remedies and Enforcement Approach

The JFTC's exclusion order (haijo sochi meirei) mandated specific actions by Provider A to remedy the situation and prevent recurrence:

- Cease Refusal: Stop refusing user requests for their registered worker data in their desired format without justifiable grounds.

- Confirm Policy Change: Formally confirm (via board resolution) that the blanket prohibition on users providing outputted documents (chōhyō) to third parties is no longer in effect and commit not to reintroduce such broad restrictions in the future.

- Notifications: Inform users and the specific competitors (Service B and C) about the cessation of the problematic conduct and the policy changes.

- Internal Compliance: Disseminate the details of the order internally, revise AMA compliance guidelines, and implement regular training and audits related to these issues.

This combination of behavioral remedies aims to restore the possibility of data migration, lower switching costs, and enable fairer competition in the market. The requirement for board resolutions and ongoing compliance measures signals the JFTC's intent to ensure long-term adherence. It's also worth noting that Provider A has reportedly filed a lawsuit seeking to revoke the JFTC's order, indicating potential ongoing legal battles over the interpretation of its conduct and the interplay between APPI and AMA.

Broader Implications and International Context

This JFTC case resonates with global trends in digital market regulation:

- Data Portability as a Competition Tool: Regulators worldwide (e.g., under the EU's GDPR and Digital Markets Act) increasingly view data portability not just as a consumer right but as a vital mechanism for promoting competition by reducing lock-in and facilitating entry for new players. The JFTC's action aligns with this perspective, applying it within the Japanese legal framework.

- B2B Platforms Matter: While consumer-facing platforms often dominate headlines, this case underscores that data lock-in and switching costs can be equally potent competitive issues in B2B cloud service markets, particularly where platforms become deeply integrated into industry workflows and hold essential operational data.

- Privacy as a Shield vs. Sword: The case highlights the delicate balance regulators must strike. While enforcing genuine data protection compliance is crucial, they must also remain vigilant against dominant firms potentially using privacy obligations as a "shield" to justify anti-competitive conduct. The JFTC's intervention suggests a move towards scrutinizing the proportionality and competitive intent behind data restriction measures justified on privacy grounds.

- Design for Portability: For platform providers, particularly those operating in concentrated markets or holding significant user data, there is a growing expectation to design systems with data portability in mind from the outset, rather than creating technical architectures that make later export difficult or impossible.

- User Due Diligence: For businesses relying on specialized B2B cloud services, this case serves as a reminder to carefully assess data ownership, access, and export capabilities during vendor selection and contract negotiation. Understanding potential switching costs and data lock-in risks is crucial strategic foresight.

Conclusion: Data Flow and Fair Competition in Japan

The JFTC's action against restrictive data transfer practices sends a clear signal: leveraging control over user data to create artificial lock-in and unfairly hinder competitors is likely to violate Japan's Antimonopoly Act. While compliance with data protection laws like the APPI is a non-negotiable requirement, it cannot serve as a blanket justification for anti-competitive strategies that prevent users from exercising reasonable control over their own information and switching service providers.

This case underscores the dynamic interplay between competition policy, data protection, and technological design in Japan's evolving digital economy. Businesses, whether providing or utilizing digital platforms and cloud services, must navigate this landscape carefully. This involves not only adhering to the APPI's requirements but also ensuring that data governance policies and technical architectures facilitate, rather than impede, legitimate data portability and fair competition. As the JFTC continues to focus on digital markets, scrutiny of data-related conduct that raises switching costs or excludes rivals is likely to remain a key enforcement priority.

- Antitrust Oversight in Japanese M&A: Understanding Merger Control and the Role of Monitoring Trustees

- Japan Targets Mobile Ecosystems: Inside the Smartphone Software Competition Promotion Act

- Data Privacy in Japanese Criminal Investigations: A Guide for US Multinationals

- JFTC — Guidelines on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position in Digital Markets

https://www.jftc.go.jp/en/policy_enforcement/docs/abuse_of_superior_bargaining_position_digital.pdf