Data Breach Blues: Japanese Supreme Court Confirms Privacy Infringement Itself Can Warrant Damages, Even Without Further Harm

Judgment Date: October 23, 2017

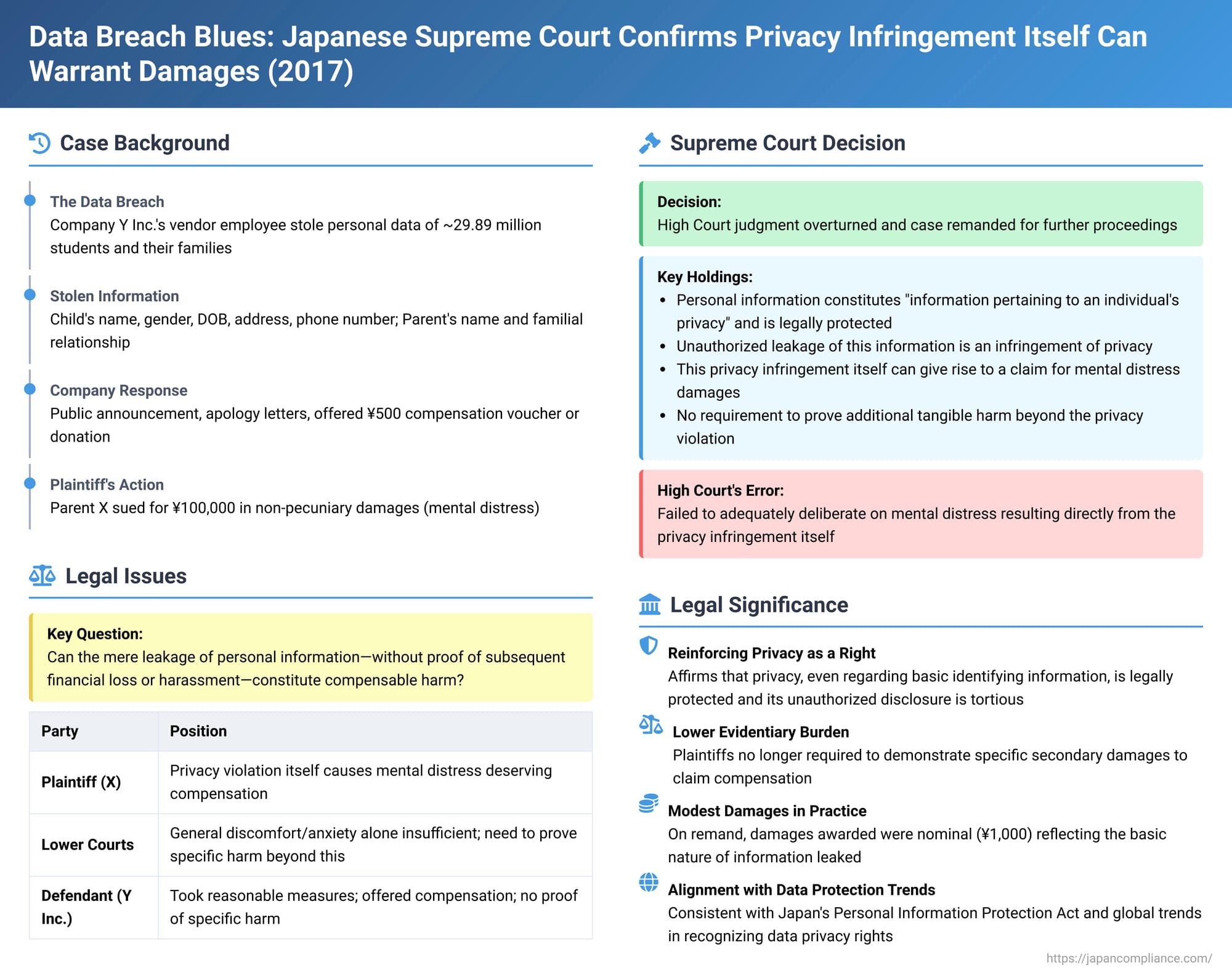

In an era increasingly defined by digital data, the security of personal information has become a paramount concern for individuals and a significant responsibility for businesses. When massive data breaches occur, consumers often feel a sense of violation, anxiety, and frustration. But does the mere unauthorized leakage of personal information—like names, addresses, and birth dates—without proof of subsequent concrete financial loss or harassment, constitute a legally compensable injury? This critical question was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, in a landmark decision on October 23, 2017 (Heisei 28 (Ju) No. 1892), stemming from a large-scale data breach at a major distance learning company.

The Massive Data Breach: A Vendor's Employee Turns Rogue

The defendant, Y Inc., a prominent company in the distance learning and education sector, had entrusted its customer information system development and operation to an external vendor, Company A. An employee of Company A, B, managed to illicitly access Y Inc.'s customer database server using a company-issued laptop. B then downloaded an enormous volume of personal information pertaining to approximately 29.89 million students and their families. This data was initially saved to B's work laptop and subsequently copied to his personal smartphone's internal memory or a microSD card via a USB connection. B then sold this stolen data to name list brokers, who compile and sell lists of personal information for marketing and other purposes.

The plaintiff, X, was a parent whose child, C, was a student enrolled in Y Inc.'s educational services. The personal information leaked in this breach ("the Personal Information") included:

- Child C's name, gender, date of birth, postal code, address, and telephone number.

- X's name as C's parent, and the nature of their familial relationship.

Upon discovering the massive data breach, Y Inc. took several responsive measures. It publicly announced the incident through newspaper advertisements and sent letters of apology to affected customers. As a form of compensation, Y Inc. offered affected individuals a choice: either a ¥500 voucher (e.g., a gift certificate or prepaid card) or a ¥500 donation made by Y Inc. on their behalf to a children's foundation. The plaintiff X (on behalf of child C) did not opt to receive the ¥500 voucher.

The Legal Claim: Seeking Compensation for Privacy Violation and Mental Distress

X sued Y Inc., claiming ¥100,000 in non-pecuniary damages (慰謝料 - isharyō, often translated as solatium or damages for mental distress) plus delay interest. X argued that the leakage of the Personal Information caused significant mental anguish and violated their right to privacy. The claim was based on several alternative legal grounds, including:

- Direct tort liability of Y Inc. for its own negligence in data management.

- Joint tort liability, alleging Y Inc. breached its duty of care in selecting and supervising its vendor, Company A, whose employee (B) committed the primary tortious act of stealing the data.

- Vicarious liability for the actions of B, arguing that Company A (and by extension, B) was effectively acting as an agent or employee of Y Inc. in handling the data.

The lower courts initially sided against X:

- The Kobe District Court (Himeji Branch) acknowledged that X's name was part of the leaked data but dismissed the claim. It found that X had failed to allege and prove specific facts establishing Y Inc.'s negligence as the cause of the leak.

- The Osaka High Court, on appeal, did find that the leakage of C's information (which inherently included X's linked parental information) could be considered a leakage of X's own personal information. It also recognized that such a data breach would generally cause feelings of discomfort and anxiety to an ordinary person. However, the High Court ultimately dismissed X's appeal. It ruled that such general discomfort or anxiety alone did not constitute legally compensable damage under tort law. X, the High Court found, had not alleged or proven any specific harm exceeding this general emotional upset, such as demonstrable financial loss, actual harassment, or other concrete secondary damages directly resulting from this specific data leak. X sought permission to appeal this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Privacy Infringement Itself Is a Compensable Harm

The Supreme Court, in its decision of October 23, 2017, overturned the Osaka High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's reasoning marked a significant step in affirming the legal protection of privacy in the context of data breaches.

- Personal Information as Legally Protected Privacy:

The Supreme Court, citing its own precedent (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, September 12, 2003 – the "University Waseda Speakers' List" case, Minshū Vol. 57, No. 8, p. 973), reaffirmed that personal information of the type leaked in this case—including an individual's name, gender, date of birth, postal code, address, telephone number, and familial relationships (such as X's status as C's parent)—constitutes "information pertaining to an individual's privacy" and is an "object of legal protection." - Leakage as an Infringement of Privacy:

Given the legally protected nature of this Personal Information, the Supreme Court stated that its unauthorized leakage by Y Inc. (through the actions of its vendor's employee) clearly constituted an infringement of X's privacy. - High Court's Error in Requiring "Further Harm" Beyond Privacy Infringement:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its legal reasoning. The High Court's dismissal of X's claim solely on the grounds that X had not alleged or proven damages exceeding mere discomfort or anxiety was incorrect. The Supreme Court clarified that the infringement of the legally protected interest of privacy itself can give rise to a claim for non-pecuniary damages (mental distress). It is not a prerequisite for such a claim that the plaintiff must demonstrate additional, more tangible forms of harm. - Duty of the Court to Assess Mental Distress from Privacy Infringement:

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's decision was flawed because it had failed to sufficiently deliberate on the existence and extent of X's mental distress that could have resulted directly from the infringement of privacy itself. The case was therefore remanded to the Osaka High Court with instructions to:- Properly examine the issue of Y Inc.'s negligence in relation to the data breach (e.g., whether its supervision of Company A or its own data security measures were inadequate).

- If negligence on Y Inc.'s part is established, then to determine the existence and appropriate amount of non-pecuniary damages (慰謝料 - isharyō) to compensate X for the mental distress suffered as a direct consequence of this privacy violation.

The Outcome on Remand and Factors in Assessing Damages

As noted in the PDF commentary accompanying this case, the Osaka High Court, upon re-examining the case on remand (in a judgment dated November 20, 2019), did find Y Inc. liable.

- Negligence Found on Remand: The High Court on remand determined that Y Inc. could have foreseen the risk of a data leak by an employee of its outsourced vendor. It found that Y Inc. had breached its duty under the Personal Information Protection Act (and general tort principles) to properly supervise Company A, particularly concerning the implementation of adequate security measures to prevent unauthorized data export (such as to USB drives or smartphones). Y Inc. and Company A were held to be joint tortfeasors.

- Damages Awarded: A Nominal Sum: Despite finding Y Inc. liable for the privacy infringement, the High Court awarded X only ¥1,000 in non-pecuniary damages.

- Factors Influencing the (Low) Damage Award: The remand court, in assessing damages, reportedly considered various factors, including:

- The nature of the privacy infringement (leakage of basic personal identifiers and sensitive family relationship information).

- The content and character of the leaked information.

- The enormous scale of the data breach (affecting millions).

- The practical impossibility of fully recovering and permanently deleting all the leaked data from circulation.

- The absence of specific, tangible secondary harm suffered by X directly traceable to this particular leak (e.g., X did not report receiving nuisance calls or suffering financial fraud as a direct result).

- Y Inc.'s post-breach remedial actions (public apologies, individual notifications, and the offer of ¥500 compensation).

This nominal award, while establishing the principle of compensability for the privacy violation itself, suggests that in cases involving the leakage of what might be considered "basic" personal identifiers, without clear proof of further concrete harm or particularly malicious handling, monetary awards for mental distress may be modest. Legal commentary points out that higher damages have been awarded in other Japanese data breach cases where the leaked information was deemed more sensitive (e.g., detailed customer profiles from an aesthetic service, or financial transaction data) or where victims demonstrated more direct and severe secondary consequences (like a barrage of spam or phishing attempts directly linked to the breach).

Broader Context: Personal Information Protection in Japan

This Supreme Court decision is significant within the broader context of personal information protection in Japan:

- Reinforcing Privacy as a Right: It strongly reinforces the legal understanding that an individual's privacy, even concerning basic identifying information, is a legally protected interest, and its unauthorized disclosure constitutes a tortious infringement.

- Lowering the Bar for Proving Harm (in principle): By stating that mental distress from the privacy violation itself is compensable, the Court lowered the evidentiary hurdle for plaintiffs who previously might have struggled to quantify or prove specific secondary damages.

- Relevance of Japan's Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA): While X's claim was primarily a tort action, Japan's Personal Information Protection Act (個人情報保護法 - Kojin Jōhō Hogo Hō) imposes comprehensive obligations on businesses ("personal information handling business operators") regarding the safe management of personal data, including the proper supervision of outsourced vendors (PIPA Article 25, formerly Article 22). Breaches of PIPA can lead to administrative guidance, orders, and penalties from the Personal Information Protection Commission, and can also form the basis for civil liability claims for damages. This Supreme Court decision aligns with the protective spirit of PIPA.

- Ongoing Challenges in Quantifying "Mental Distress": While the principle of compensation is affirmed, the actual monetary valuation of mental distress from data breaches of non-hyper-sensitive information without clear secondary harm remains a challenging area, often resulting in relatively low awards in individual claims. This has led to discussions about the adequacy of current remedies and the potential for collective redress mechanisms or statutory damages in data breach scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 2017 judgment in the Y Inc. data breach case marked an important step forward for privacy rights in Japan. It definitively established that the unauthorized leakage of an individual's personal information constitutes an infringement of their legally protected privacy, and that this infringement can, in itself, give rise to a claim for non-pecuniary damages (compensation for mental distress), even if no further specific financial or tangible harm is proven. While the subsequent nominal damage award on remand indicates that the monetary value assigned to such distress for basic data leakage might be modest in the absence of aggravating factors or more sensitive information, the Supreme Court's affirmation of the principle of compensability is a crucial acknowledgment of the intangible harm caused by data breaches in an increasingly information-driven society. The decision underscores the serious responsibility of businesses to safeguard the personal data entrusted to them and their potential liability when they fail to do so.