Categorical Offset Principle: Japan's Supreme Court on Social Insurance Deduction in Tort Claims (1987)

Japan’s Supreme Court held in 1987 that workers’‑comp and disability pensions may offset only lost‑earnings damages, not medical costs or pain‑and‑suffering, cementing the categorical‑offset rule.

TL;DR

In 1987, Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that social‐insurance payments can only offset the same category of tort damages they are meant to cover. Income‑replacement benefits may reduce lost‑earnings damages, but they cannot be deducted from medical expenses or pain‑and‑suffering. The decision established the “categorical offset” rule that still governs Japanese personal‑injury cases today.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Workplace Assault, Damages, and Benefits

- Lower Court Ruling: Lump‑Sum Offset Eliminates Claim

- Legal Framework: Son'eki Sōsai and the “Same Cause/Event” Requirement

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 10 1987): Emphasizing Homogeneity

- Remand for Recalculation

- Implications and Significance: The Principle of Categorical Offset

- Conclusion

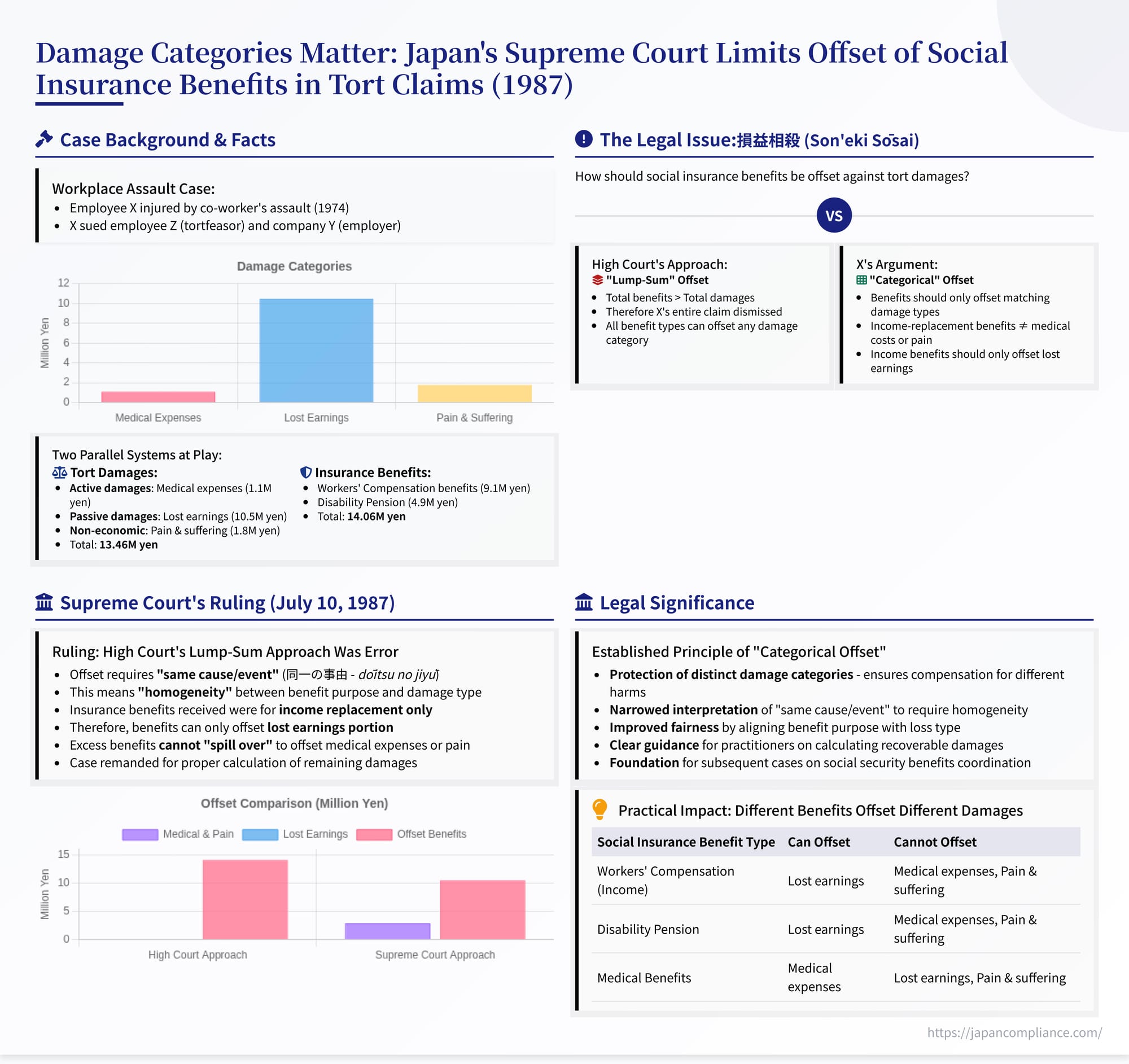

On July 10, 1987, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment clarifying the application of the principle of son'eki sōsai (損益相殺 - offsetting gains and losses) when coordinating tort damages with social insurance benefits (Case No. 1983 (O) No. 128, "Damages Claim Case"). The case involved an employee injured by a co-worker's assault who subsequently received various benefits under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act) and the Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act). The core issue was whether the entire amount of these social insurance benefits could be deducted from the total tort damages awarded, or if the deduction should be limited by matching the type of benefit to the type of damage it was intended to compensate. The Supreme Court decisively adopted the latter approach, ruling that income-replacement benefits can only offset damages for lost earnings, not other categories like medical expenses or pain and suffering. This principle of "categorical offset" based on homogeneity remains fundamental in Japanese tort law involving social security payments.

Factual Background: Workplace Assault, Damages, and Benefits

The facts underlying the legal dispute were as follows:

- The Incident: On December 19, 1974, Employee Z, acting in the course of his employment for Company Y, assaulted the appellant, X, causing injuries including cervical sprain and chest contusion ("the Accident").

- Tort Claim: X sued both Employee Z (direct tortfeasor) and Company Y (under employer liability principles) seeking damages for the harm caused by the assault.

- Assessed Damages: The High Court (acting as the lower appellate court) determined the categories and amounts of damages suffered by X due to the Accident:

- Active Damages (Medical/Related Expenses):

- Hospital Incidentals (入院雑費 - nyūin zappi): 15,500 yen

- Attendant Care Costs (付添看護費 - tsukisoi kango hi): 1,096,000 yen

- Passive Damages (Lost Earnings):

- Lost Income/Earnings Compensation (休業補償費 - kyūgyō hoshō hi): 10,545,465 yen

- Non-Economic Damages:

- Pain and Suffering (慰藉料 - isharyō): 1,800,000 yen

- Total Assessed Damages: 13,456,965 yen

- Active Damages (Medical/Related Expenses):

- Social Insurance Benefits Received: As a result of the work-related injury, X received benefits from two social insurance systems:

- Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act):

- Temporary Absence Compensation Benefit (休業補償給付 - kyūgyō hoshō kyūfu): 2,395,980 yen (compensates for lost wages during temporary disability)

- Injury and Disease Compensation Pension (傷病補償年金 - shōbyō hoshō nenkin): 6,720,384 yen (paid when injury/illness doesn't heal after 1.5 years and meets disability criteria, replacing temporary absence benefit)

- Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act, pre-1985 version):

- Disability Pension (障害年金 - shōgai nenkin): 4,946,022 yen (compensates for long-term loss of earning capacity due to disability)

- Total Social Insurance Benefits Received: 14,062,386 yen

- Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act):

Lower Court Ruling: Lump-Sum Offset Eliminates Claim

The High Court, having determined both the total damages and the total benefits received, proceeded to apply the principle of son'eki sōsai. It adopted a "lump-sum offset" approach:

- It viewed all damage categories (active, passive, non-economic) as arising from the single underlying cause – the physical injury inflicted by the assault.

- It considered all social insurance benefits received (WCAI and EPI) as essentially compensation for the overall loss resulting from this same injury.

- Therefore, it reasoned that the total benefits received (~14.06M yen) should be deducted from the total damages assessed (~13.46M yen).

- Since the total benefits exceeded the total damages, the High Court concluded that X's entire loss had already been fully compensated through the insurance payments.

- Consequently, it dismissed X's claim for damages entirely, including the claim for attorney fees (reasoning that no compensable damage remained to justify awarding litigation costs).

X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court erred in offsetting income-replacement benefits against damages for medical expenses and pain and suffering.

Legal Framework: Son'eki Sōsai and the "Same Cause/Event" Requirement

The appeal centered on the correct application of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses) in the context of social insurance benefits. This doctrine prevents double recovery by requiring that benefits received by the plaintiff due to the same event that caused their loss should be deducted from the tort damages award.

However, the deduction is not automatic or applied across the board. Legal provisions governing the coordination between tort damages and social insurance benefits (e.g., LSA Art. 84(2), WCAI Act Art. 12-4, EPI Act Art. 40) typically state that the insurance benefit substitutes for damages or that the right to damages is reduced only concerning the "same cause/event" (同一の事由 - dōitsu no jiyū). The interpretation of this phrase was key. Does it mean simply arising from the same accident, or does it imply a closer relationship between the purpose of the benefit and the nature of the specific damage item?

The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 10, 1987): Emphasizing Homogeneity

The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's lump-sum approach and adopted a more nuanced interpretation based on the nature and purpose of both the damages and the benefits. It partially overturned the High Court's decision.

1. Defining "Same Cause/Event" (Dōitsu no Jiyū):

The Court clarified that for an insurance benefit and a damages claim to relate to the "same cause/event" for offset purposes, it is not sufficient that they merely originate from the same accident. Instead, it requires that:

- The "purpose and objective" (shushi mokuteki) of the insurance benefit must coincide (itchi suru) with the purpose and objective of the specific category of civil damages being considered.

- This means the nature of the loss covered by the insurance benefit must be "homogeneous" (dōshitsu) with the nature of the loss compensated by that specific category of damages.

- In essence, the insurance benefit and the specific damage item must serve a "mutually compensatory" (sōgo hokansei o yūsuru) function, addressing the same type of harm.

2. Analyzing the Nature of the Benefits Received by X:

The Court examined the purpose of the WCAI and EPI benefits X received:

- WCAI Temporary Absence Compensation Benefit

- WCAI Injury and Disease Compensation Pension

- EPI Disability Pension

It concluded that all these benefits are primarily intended to compensate for economic loss resulting from the inability to work due to the injury or illness – i.e., passive damages (lost earnings or lost earning capacity).

3. Analyzing the Nature of Different Damage Categories:

The Court implicitly recognized the standard classification of tort damages into distinct categories representing different types of losses:

- Active Damages (積極損害 - sekkyoku songai): Out-of-pocket expenses incurred due to the tort (e.g., medical fees, nursing costs, hospital incidentals).

- Passive Damages (消極損害 - shōkyoku songai): Economic loss due to impaired ability to earn income (逸失利益 - isshitsu rieki).

- Non-Economic Damages (精神的損害 - seishinteki songai): Compensation for mental and physical pain and suffering (慰謝料 - isharyō).

4. Applying the Homogeneity Test:

Applying the "same cause/event" = "homogeneity" test, the Court determined the appropriate scope of the offset:

- The WCAI and EPI benefits received by X (which compensate for lost earning capacity) are homogeneous only with passive damages (lost earnings).

- These benefits are not homogeneous with active damages (expenses like hospital incidentals and attendant care costs) or with non-economic damages (pain and suffering). The purpose of these damage categories differs fundamentally from the income-replacement purpose of the benefits.

5. Limiting the Offset:

Therefore, the Court ruled that the offset must be performed categorically:

- The total amount of WCAI/EPI benefits received (~14.06M yen) should be deducted only from the assessed amount of lost earnings (~10.55M yen).

- Since the benefits exceeded the lost earnings in this case, the lost earnings portion of the damages was fully offset.

- However, the excess amount of benefits (~3.51M yen) cannot "spill over" to be deducted from the separate categories of active damages (hospital incidentals, nursing costs) or non-economic damages (pain and suffering).

- The right to compensation for these distinct types of losses remains unaffected by the income-replacement benefits received.

6. Consistency with Precedent on Pain and Suffering:

The Court explicitly noted that this conclusion aligns with its existing precedent, which had already established that WCAI benefits cannot be deducted from damages awarded for pain and suffering (慰謝料). This ruling extended that principle by clarifying that income-replacement benefits also cannot offset active damages like medical or nursing expenses.

Remand for Recalculation

Based on this reasoning, the High Court's decision, which had performed a lump-sum offset and dismissed X's entire claim, contained a clear error in the interpretation and application of the law regarding son'eki sōsai and the concept of "same cause/event." This error demonstrably affected the outcome.

The Supreme Court therefore partially overturned the High Court's judgment. It specified that the portion related to the claim for 2,493,050 yen (representing 70% of the non-offset damages [active + non-economic + attorney fees], reflecting X's self-admitted 30% comparative negligence) plus delay damages thereon, should be remanded. The case was sent back to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings to correctly calculate the final damages owed to X for active and non-economic losses, applying the offset only against lost earnings and taking into account the agreed-upon comparative negligence.

Implications and Significance: The Principle of Categorical Offset

The 1987 decision is a cornerstone ruling in Japanese tort law concerning the interaction with social insurance benefits:

- Establishment of Categorical Offset: It firmly established the principle that son'eki sōsai involving social insurance benefits must be applied categorically, based on the homogeneity between the purpose of the benefit and the nature of the specific damage item. A lump-sum offset across different damage categories is generally impermissible.

- Protection of Different Damage Heads: This ensures that compensation awarded for distinct types of harm, such as out-of-pocket expenses or pain and suffering, is not effectively nullified by benefits intended primarily for income replacement. It protects the integrity of each damage category.

- Defining "Same Cause/Event": It provided a crucial interpretation of the statutory phrase "same cause/event" (dōitsu no jiyū), clarifying that it requires a correspondence in the nature of the loss compensated, not just a common origin in the same accident.

- Foundation for Later Cases: This principle of homogeneity has become the foundation for numerous subsequent court decisions dealing with the complex interplay between various types of social security benefits (pensions, unemployment benefits, welfare payments) and different heads of tort damages.

- Clarity for Practitioners: It provides essential guidance for lawyers and courts in calculating net recoverable damages in personal injury and wrongful death cases where plaintiffs also receive social insurance benefits, requiring a careful matching of benefit types to damage categories before applying any offset.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 10, 1987, judgment clarified that when offsetting social insurance benefits against tort damages under the principle of son'eki sōsai, the deduction must respect the distinct nature of different damage categories. Benefits primarily aimed at compensating for lost earnings, such as those under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act and the Employees' Pension Insurance Act for disability or absence from work, can only be offset against the lost earnings (passive damages) portion of a tort award. They cannot be used to reduce compensation awarded for active damages (like medical or nursing expenses) or non-economic damages (pain and suffering), even if the total benefits received exceed the amount of lost earnings. This "categorical offset" approach ensures a fairer alignment between the purpose of the benefit and the specific type of loss being compensated.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Labour Standards: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Application Guidance for Foreign Workers (PDF)

- Pension Security — White Paper on Health, Labour and Welfare