Crossing Borders Digitally: Japan Redefines Patent Territoriality for Network Systems

TL;DR

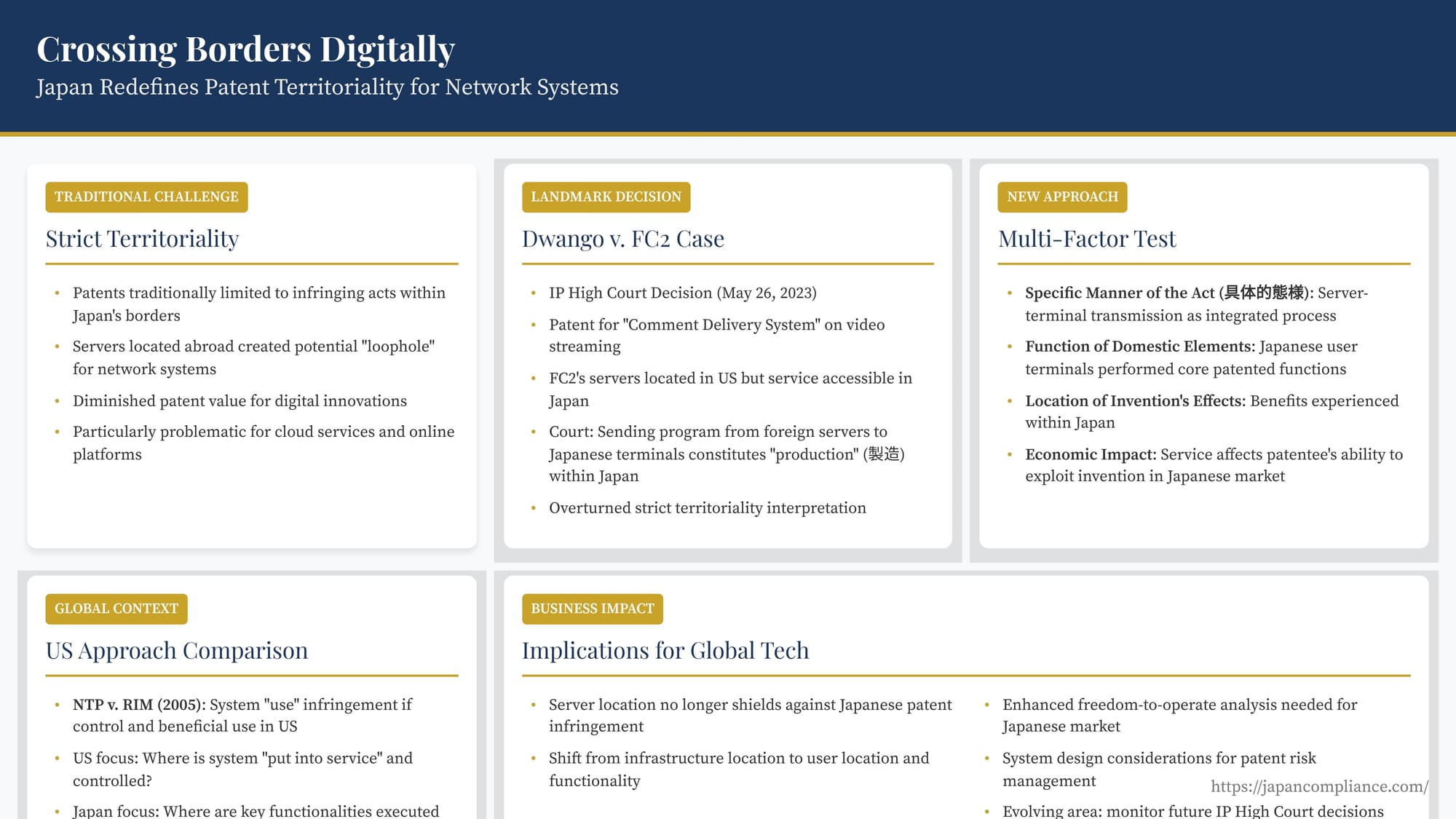

- Japan’s IP High Court (May 26 2023) adopted a multi-factor “substantive territoriality” test, letting patents reach digital systems whose servers sit abroad but whose core functions and effects occur in Japan.

- Key factors: manner of the act, domestic role of claim elements, place where effects arise, and economic impact on the patentee.

- Tech firms can no longer rely on offshore hosting to avoid Japanese infringement; robust FTO reviews for services accessible in Japan are essential.

Table of Contents

- The Traditional Hurdle: Strict Territoriality and Digital Services

- The Dwango v. FC2 Patent Infringement Case (System Patent)

- The IP High Court's New Approach: Substantive Territoriality (May 26 2023 Decision)

- Consistency and Context: A Developing Trend

- Comparison with US Patent Law

- Implications for Global Technology Businesses

- Conclusion: A New Standard for the Digital Age

The principle of territoriality lies at the heart of patent law: a patent granted in one country generally only provides protection against infringing acts occurring within that country's borders. While straightforward for traditional physical goods, applying this principle to globally distributed network systems, cloud services, and online platforms presents significant challenges. When servers are located in one country, software developers in another, and users accessing the service in yet a third (the patent-holding country), where does the "infringement" occur?

This complex question is forcing courts worldwide to reconsider traditional interpretations. A landmark decision by Japan's Intellectual Property (IP) High Court on May 26, 2023, in a case involving online video services (Dwango v. FC2), signals a significant evolution in Japanese patent law, moving towards a more flexible, substantive analysis that could have broad implications for technology companies offering services accessible in Japan, regardless of where their servers are physically located.

The Traditional Hurdle: Strict Territoriality and Digital Services

Historically, a strict application of territoriality often meant that if a key component of an allegedly infringing system, such as the main server processing data or delivering content, was located outside Japan, it could be difficult to establish patent infringement under Japanese law, even if the service was actively used by consumers within Japan. This created a potential loophole, allowing companies to arguably circumvent Japanese patents simply by hosting their infrastructure abroad, thereby undermining the economic value of patents covering network-based inventions used in the Japanese market.

The Dwango v. FC2 Patent Infringement Case (System Patent)

The case (IP High Court Case No. 2022 [Ne] 10046) involved Dwango Co., Ltd., a Japanese media and technology company, and FC2, Inc., a US-based web service provider, along with a related company. Dwango holds a Japanese patent (No. 6526304) for a "Comment Delivery System," which relates to technology for displaying user comments overlaid on streaming video in a way that prevents them from overlapping excessively.

Dwango alleged that FC2's video streaming service, accessible to users in Japan, infringed this patent. A key point of contention was whether FC2's actions constituted an infringing act within Japan. FC2's servers were located outside Japan (in the US). Dwango argued that the act of FC2 sending the necessary program files and data from its US servers to user terminals located within Japan, which then executed the software to display the video and comments according to the patented method, constituted "production" (生産 - seisan, one of the exclusive acts defined under Japan's Patent Act Art. 2(3)) of the patented system within Japan.

The Tokyo District Court initially dismissed Dwango's claim, adhering to a stricter view of territoriality – since the servers were abroad, the "production" was not completed within Japan. Dwango appealed to the IP High Court.

The IP High Court's New Approach: Substantive Territoriality (May 26, 2023 Decision)

The IP High Court reversed the District Court's decision, finding that FC2's actions could indeed constitute patent infringement within Japan. The court explicitly acknowledged the inadequacy of a rigid territoriality interpretation for modern network systems.

Rationale for Flexibility:

The court reasoned that:

- Locating servers abroad is now commonplace and doesn't inherently hinder the use or effectiveness of a network system within Japan.

- Allowing companies to easily avoid Japanese patents simply by placing servers offshore would fail to provide adequate protection for inventions whose economic value is realized through domestic use.

- Conversely, automatically finding infringement merely because a user terminal is located domestically could lead to overprotection and hinder legitimate economic activity.

The Multi-Factor Test for Domestic Infringement:

Based on this reasoning, the court established that even if parts of a system (like servers) are located outside Japan, the act of "producing" the system could be deemed to have occurred within Japan if, after comprehensively considering (総合考慮 - sōgō kōryo) various factors, the act can be substantively and overall evaluated as such. The court highlighted four key factors:

- The Specific Manner of the Act (具体的態様 - gutaiteki taiyō): How is the system brought into being or made available? In this case, the court focused on the integrated act of transmission from the foreign server and reception by the domestic user terminal, concluding that the system was only completed and functional upon reception within Japan. This integral trans-border process could be conceptually viewed as occurring domestically.

- The Function and Role of Domestic Elements within the Patented Invention (当該システムを構成する各要素のうち国内に存在するものが当該発明において果たす機能・役割 - tōgai shisutemu o kōsei suru kaku yōso no uchi kokunai ni sonzai suru mono ga tōgai hatsumei ni oite hatasu kinō/yakuwari): What essential parts of the patented invention are performed or located within Japan? The court found that the user terminals in Japan performed core functions claimed in Dwango's patent – specifically, the determination and control logic for displaying comments without overlap (corresponding to the patent's "determination part" and "display position control part").

- The Location Where the Invention's Effects are Obtained (当該システムの利用によって当該発明の効果が得られる場所 - tōgai shisutemu no riyō ni yotte tōgai hatsumei no kōka ga erareru basho): Where do the benefits or results of using the invention manifest? Here, the court determined that the system was used via terminals within Japan, and the invention's effect – enhancing user entertainment through interactive commenting – was primarily experienced by users located in Japan.

- The Impact on the Patentee's Economic Interests (その利用が当該発明の特許権者の経済的利益に与える影響 - sono riyō ga tōgai hatsumei no tokkyokenja no keizaiteki rieki ni ataeru eikyō): Does the use of the system within Japan affect the patent holder's ability to exploit their patent economically within the Japanese market? The court concluded that FC2's service, used by Japanese users, could directly impact the economic benefits Dwango could derive from its patented system in Japan.

Applying the Test: Weighing these factors, the IP High Court concluded that FC2's act of transmitting files to enable the comment overlay system on user terminals in Japan constituted "production" of the patented system within Japan's territory for the purposes of infringement analysis.

Consistency and Context: A Developing Trend

This May 2023 decision is not an isolated event. It builds upon a previous ruling by the same IP High Court division in a related case between the same parties (Dwango v. FC2, July 20, 2022, Case No. 2018 [Ne] 10077). That earlier case involved infringement allegations concerning a different Dwango patent related to a program (rather than a system) and the infringing act was argued as "provision" (提供 - teikyō) of the program (e.g., via transmission) rather than "production."

In the July 2022 decision, the court also adopted a flexible, substantive approach to territoriality for the act of "provision." It similarly held that even if not all elements of the act occur domestically, it can be considered infringement in Japan if it can be evaluated as such "substantively and overall." The factors listed in the 2022 decision for assessing "provision" were slightly different but conceptually related: (i) ability to clearly distinguish domestic/foreign parts of the provision, (ii) location of control over the provision, (iii) whether the provision targets customers in Japan, and (iv) whether the invention's effects manifest in Japan.

The May 2023 decision concerning "production" of a system confirms and refines this move away from rigid territoriality. While the specific factors enumerated may differ slightly depending on the type of invention (system vs. program) and the specific infringing act alleged (production vs. provision vs. use), the underlying principle of a comprehensive, substantive evaluation considering domestic elements, effects, and economic impact appears to be solidifying in Japanese IP case law for network-related inventions.

Comparison with US Patent Law

The challenge of applying territoriality to cross-border digital infringement is also well-recognized in the United States, although the legal doctrines differ. US patent law (35 U.S.C. § 271) addresses infringement through acts like making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the patented invention within the United States.

For system claims, the key question often revolves around whether the system has been "used" within the US under § 271(a). Case law, notably NTP, Inc. v. Research In Motion, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2005), established that the location of the entire system need not be within the US. Infringement can occur if control of the system is exercised and the system's beneficial use and function are obtained within the United States, even if some components (like servers) are located abroad. The focus is often on where the system as a whole is "put into service."

Other provisions address specific cross-border scenarios:

- § 271(f): Infringement by supplying components from the US with the intent that they be combined abroad to make a patented invention.

- § 271(g): Infringement by importing, selling, offering to sell, or using within the US a product made by a process patented in the US, even if the process was performed abroad.

Comparing the Japanese approach in Dwango v. FC2 with US law reveals both similarities and differences. Both systems grapple with adapting territoriality to distributed systems. However:

- The US "use" analysis under § 271(a), following NTP v. RIM, often centers on the location of control and beneficial use of the system as a whole.

- The Japanese IP High Court's multi-factor test appears potentially broader or at least differently focused, giving significant weight to where key functionalities defined by the patent claims are executed (even if on a user terminal) and where the effects and economic impact occur, alongside the manner of the act itself (like the server-terminal transmission completing the system in Japan). The Japanese test might find infringement even if overall system control resides abroad, provided essential claim functions and effects manifest domestically.

Implications for Global Technology Businesses

The Dwango v. FC2 decisions have significant practical implications for US and other foreign technology companies whose services or platforms are accessible in Japan:

- Increased Infringement Risk: Simply locating servers outside Japan is no longer a reliable shield against Japanese patent infringement claims for network-based systems or services actively used by Japanese consumers.

- Focus Shifts to Users and Functionality: The analysis shifts focus from server location to where the users are, where the essential functions of the patented invention are performed (potentially including user devices), and where the invention's benefits are enjoyed.

- Enhanced Due Diligence: Companies offering online services, cloud platforms, streaming media, or other network-based systems accessible in Japan need to conduct thorough freedom-to-operate (FTO) analyses considering relevant Japanese patents, even if their primary infrastructure is hosted elsewhere.

- System Architecture Considerations: While likely driven by many factors, the potential for Japanese patent infringement liability might become a consideration in designing system architectures, particularly regarding which functions are performed server-side versus client-side for the Japanese market.

- Need for Monitoring: This is an evolving area of law. Companies need to monitor future decisions from the IP High Court and potentially the Supreme Court of Japan to see how this substantive approach to territoriality is further developed and applied to different technologies and factual scenarios.

Conclusion: A New Standard for the Digital Age

The Japanese IP High Court's decisions in the Dwango v. FC2 cases represent a clear and important step in adapting patent law's traditional territorial boundaries to the realities of modern, globally distributed technology. By moving away from a rigid, location-of-components test towards a more substantive, multi-factor analysis considering domestic functions, effects, and economic impact, the court aims to provide meaningful protection for network-related inventions exploited in the Japanese market. For international technology companies, this signifies that engaging with Japanese users and delivering the effects of patented technology within Japan can trigger infringement liability, regardless of server geography. Proactive patent risk assessment and careful consideration of the Japanese legal landscape are now more critical than ever for businesses operating in the interconnected digital world.

- Patent Litigation Across the Pacific: Key Differences Between the US and Japanese Systems

- Beyond Design Patents: Protecting Product Shapes in Japan via Copyright and Unfair Competition Law

- Cross-Border Trade-Secret Protection: New Rules for Jurisdiction and Governing Law in Japan

- Japan Patent Office – IP High Court Decisions Digest (Japanese)

- IP High Court – Case Search Portal (Japanese)