Cross-Border Data Access & Platform Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Tackles Online Obscenity Case (2021)

Investigating crimes in the digital realm often involves navigating complex jurisdictional issues and grappling with the responsibility of online platforms for user-generated content. A landmark decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on February 1, 2021, addressed both these frontiers. The case concerned the operators of a major internet site hosting obscene content and involved police conducting remote access searches on servers potentially located overseas. The ruling provides crucial insights into the legality of cross-border digital evidence gathering and the criminal liability of website administrators for illegal content shared on their platforms.

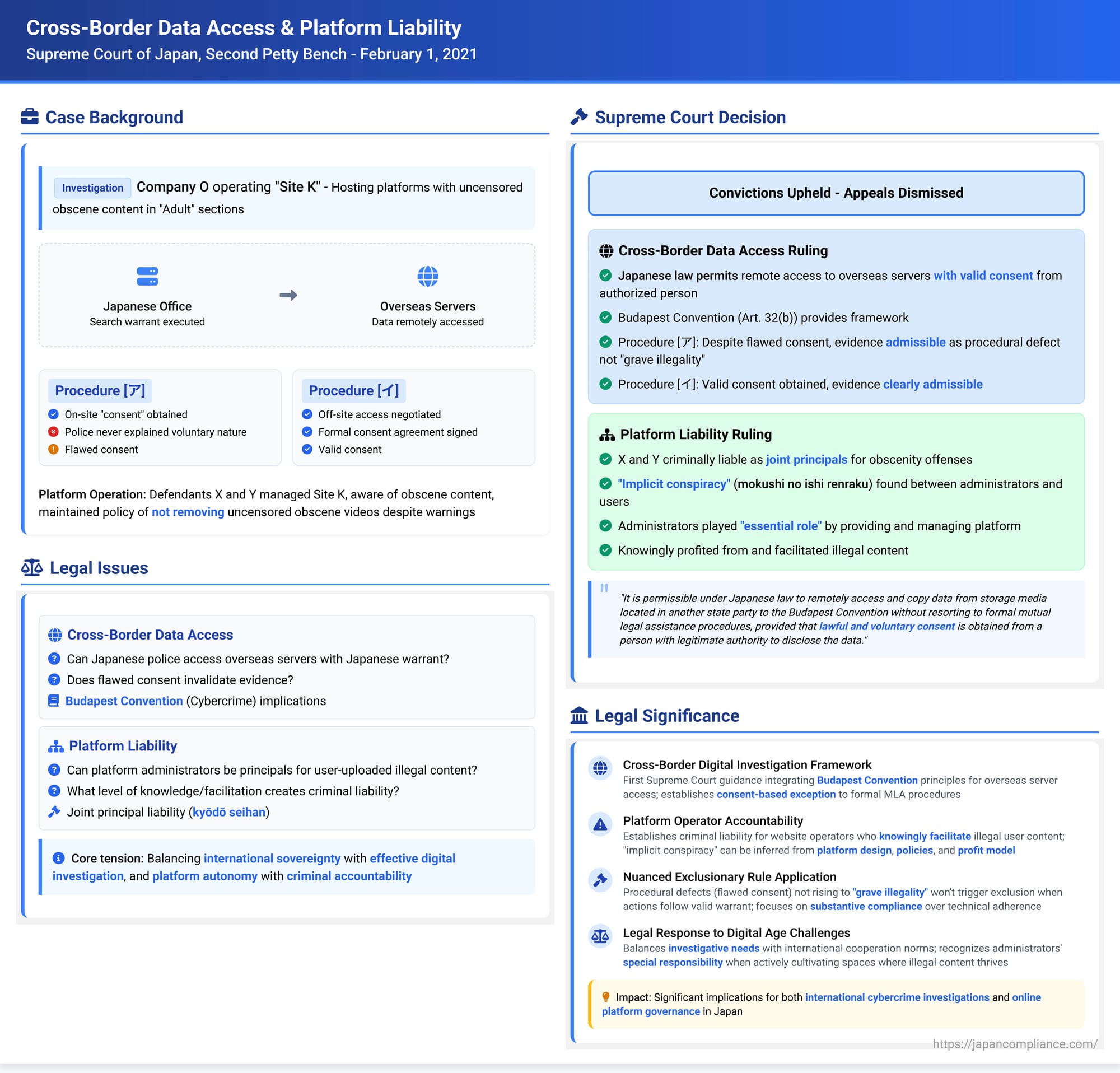

The Case: Obscenity on Site K and Overseas Servers

The case centered around two individuals, X and Y, who, along with a third person Z, managed the operations of "Company O," the company running the internet portal "Site K." Site K hosted user-generated content platforms, including "K Videos" (for uploaded videos) and "K Live" (for live streaming). Both platforms featured popular "Adult" categories.

The Investigation and Remote Access

Police suspected that X, Y, and Z were conspiring to aid public indecency and commit other violations related to Site K. Specifically, the "Adult" sections of K Videos and K Live were known to host a significant amount of uncensored obscene material (無修正わいせつ動画 - mushūsei waisetsu dōga), depicting explicit sexual acts.

- The Warrant: Investigators obtained a comprehensive search, seizure, and copying warrant targeting Company O's office. The warrant authorized the seizure of physical items like computers. Critically, it also explicitly permitted remote access copying of electromagnetic records (as allowed by Article 218, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure) from connected storage media, specifically identifying "recording areas of file storage servers accessible from the personal computers to be seized... used by the users of said personal computers" and similar recording areas on email servers containing user emails.

- Overseas Server Concerns: Before executing the warrant, police recognized a potential complication: Company O appeared to use services, including email, provided by "Company A," a major tech company headquartered in the United States. Accessing servers located in the US using a Japanese warrant could raise issues of violating foreign sovereignty.

- Investigative Strategy: To address this, the police internally decided that if they confirmed data resided on overseas servers, they would refrain from compelling remote access under the warrant's authority. Instead, they would attempt to obtain voluntary consent from the relevant computer users (employees and executives of Company O) to access the data.

- Procedure [ア] - On-Site "Consent": During the search of Company O's office starting September 30, 2014, police followed this strategy. They requested consent from personnel, including defendants X and Y, to access email and file servers remotely. After obtaining account credentials (usernames/passwords), they conducted remote access and copied data (emails, etc.). The computers used for this process were then obtained from defendant Y through voluntary submission. However, a key finding, later deemed "not unreasonable" by the Supreme Court, was that the police never clearly explained to the Company O personnel that this remote access was a voluntary procedure. The personnel likely misunderstood it as a compulsory part of the warrant execution. Therefore, the consent obtained under Procedure [ア] was considered legally flawed.

- Procedure [イ] - Off-Site Agreed Access: The initial on-site data copying proved extremely time-consuming and disruptive to Company O's business. Company O itself proposed a solution: they would provide the police with dedicated accounts allowing access to the necessary servers, enabling the police to download the required data from their own facilities (outside Company O's office). Extensive negotiations involving Company O executives, police, and Company O's lawyers followed. Ultimately, defendant Y signed a formal consent agreement on October 3, 2014. Based on this agreement, police conducted further remote access and data copying from their own locations.

- Server Location: The storage media accessed in both Procedure [ア] and Procedure [イ] were confirmed or highly likely to be located outside Japan. There was no evidence that any foreign nation objected to the access.

The Platform Liability Issue

Beyond the evidence gathering, the case also focused on the criminal responsibility of X and Y for the obscene content itself, which was uploaded or streamed by users of Site K (individuals anonymized as B, C, D, E, etc.). Key facts included:

- Site K, particularly its Adult sections, was highly profitable, largely due to the obscene content. X, Y, and Z were aware of this and the specific high-earning "agents" managing performers on K Live's adult section.

- While Site K removed extreme content like child pornography, it had an explicit policy of not removing uncensored obscene videos from the Adult categories.

- X, Y, and Z had been repeatedly warned by lawyers that this policy could lead to criminal prosecution in Japan, regardless of US law.

- Despite these warnings and even a police investigation into one user, they maintained the policy, effectively facilitating the continued display of illegal content.

- Users posted/streamed the content, motivated by the site's features and lack of enforcement against obscenity.

The Supreme Court's Rulings (February 1, 2021)

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions of X and Y, addressing both the admissibility of the remotely accessed evidence and their liability as principals.

1. Admissibility of Remotely Accessed Evidence

- Legality of Cross-Border Remote Access: The Court interpreted the relevant Code of Criminal Procedure provisions (Arts. 99(2), 218(2)) in light of their legislative history (enacted partly to implement the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime - the "Budapest Convention") and the Convention itself (specifically Art. 32(b)). It concluded:

- Japanese law does not limit remote access copying solely to domestic servers.

- It is permissible under Japanese law to remotely access and copy data from storage media located in another state party to the Budapest Convention without resorting to formal mutual legal assistance (MLA) procedures, provided that lawful and voluntary consent is obtained from a person with legitimate authority to disclose the data. This directly incorporates the consent-based exception allowed by the Convention.

- Admissibility of Procedure [ア] Evidence (Flawed Consent):

- The Court acknowledged the consent was flawed and thus didn't meet the Budapest Convention standard for consent-based access, nor was it valid as a purely voluntary investigation.

- However, the Court viewed Procedure [ア] as being conducted in substance based on the validly issued Japanese search/seizure/copying warrant. The police actions mirrored warrant execution, targeted evidence specified in the warrant, and did not exceed the scope authorized by the warrant.

- The police's initial decision to seek consent rather than use MLA for potential overseas servers was not deemed improper in itself.

- While failing to clarify the voluntary nature was a defect, there was no evidence of coercion or a deliberate intent to circumvent the warrant system's protections.

- Conclusion on [ア]: The procedural flaw did not amount to a "grave illegality" (jūdai na ihō) that would trigger the exclusionary rule. The evidence obtained was admissible.

- Legality of Wholesale Copying During Remote Access: The Court rejected the argument that copying data without confirming the relevance of each file violated particularity rules. It reaffirmed the principle from its 1998 decision (the Aum case): Where there is a probability that the target data contains relevant information, and on-site verification poses difficulties (like confirming relevance within vast data volumes) or risks (like data destruction or alteration), it is permissible to copy the data wholesale without individual checks. This applied here.

- Admissibility of Procedure [イ] Evidence (Valid Consent): The Court found no reason to overturn the lower court's finding that the consent obtained for Procedure [イ] (after negotiation with lawyers involved) was valid and voluntary. Given this valid consent, and the principles allowing consent-based cross-border access under the Budapest Convention framework, there was no grave illegality. This evidence was also admissible.

- Supplementary Opinion (Justice Miura): Justice Miura added a point clarifying that even if it's uncertain whether the server is in a Budapest Convention state party, admissibility should still be judged based on all circumstances, especially the validity of consent from an authorized person.

2. Criminal Liability of Platform Administrators (X and Y)

The Court found X and Y criminally liable as joint principals (kyōdō seihan) for the offenses of displaying obscene electromagnetic records/media (刑法175条1項後段 - Penal Code Art. 175(1), latter part) and public indecency (刑法174条 - Penal Code Art. 174), alongside the users who posted/streamed the content.

- Implicit Conspiracy: The Court determined there was an "implicit meeting of the minds" (黙示の意思連絡 - mokushi no ishi renraku) between the administrators (X, Y, Z) and the users. This was inferred from:

- The administrators' knowledge that obscene content was highly likely to be present.

- Their intent to profit from this content and make it publicly available via Site K.

- The site's design, features (rewards, rankings, etc.), and operational policies (specifically, not deleting uncensored obscenity) actively encouraged users to post/stream such content.

- The users responding to these incentives with the intent to display their content publicly.

- Essential Contribution (jūyō na yakuwari): The crimes were directly committed by the users posting or streaming. However, the administrators played an indispensable role by providing and managing the platform (Site K) that made the public display possible. Without their infrastructure and permissive policies, the users could not have committed the offenses. Furthermore, regarding the profit-driven live streaming (public indecency), the administrators shared the financial motive with the users/agents.

- Conclusion on Liability: Given the implicit conspiracy and the essential contribution of both parties, the Court held that convicting X and Y as joint principals alongside the users was justified under Japanese criminal law.

Key Legal Principles and Implications

This 2021 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for several reasons:

- Cross-Border Digital Investigations: It provides the first clear Supreme Court guidance on remote access searches targeting overseas servers. It integrates the framework of the Budapest Convention, recognizing that voluntary consent from an authorized party can, in cases involving other Convention states, bypass the need for slower, more formal MLA procedures. This offers a potentially more efficient route for international cybercrime investigations.

- Exclusionary Rule Application: The ruling demonstrates a nuanced application of the exclusionary rule. Even though the consent in Procedure [ア] was flawed, the Court focused on the substance of the action (it mirrored a warrant execution) and the lack of bad faith or grave procedural violation, declining to exclude the evidence. This suggests minor procedural defects, especially when actions are otherwise anchored to a valid warrant, may not automatically trigger exclusion.

- Bulk Digital Data Copying: It reinforces the precedent allowing comprehensive copying of digital data when relevance is probable but on-site verification is impractical or risky, solidifying a necessary tool for digital forensics in Japan.

- Platform Liability for User Content: This is perhaps the most impactful aspect for online businesses. The decision sets a strong precedent that website operators who knowingly create, manage, and profit from a platform that facilitates illegal user-generated content (like obscenity), and who maintain policies that allow such content despite warnings, can be held criminally liable as joint principals with the users. The finding of an "implicit conspiracy" based on site structure and operational choices sends a clear message about the responsibilities of platform administrators under Japanese criminal law.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 1, 2021, ruling significantly advances Japanese law's response to the challenges of the digital age. It clarifies the legal pathways for conducting cross-border remote access searches, balancing international cooperation norms with investigative needs. Concurrently, it establishes a robust standard for the criminal liability of online platform operators who actively cultivate and profit from environments where illegal user content thrives. This decision has profound implications for both international law enforcement cooperation and the responsibilities of internet businesses operating in or serving Japan.