Creditor's Reach vs. Policyholder's Shield: Japanese Supreme Court on Seizing Life Insurance Cash Surrender Value

Date of Judgment: September 9, 1999

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 456 (Ju) of 1998 (Claim for Collection of Attached Debt)

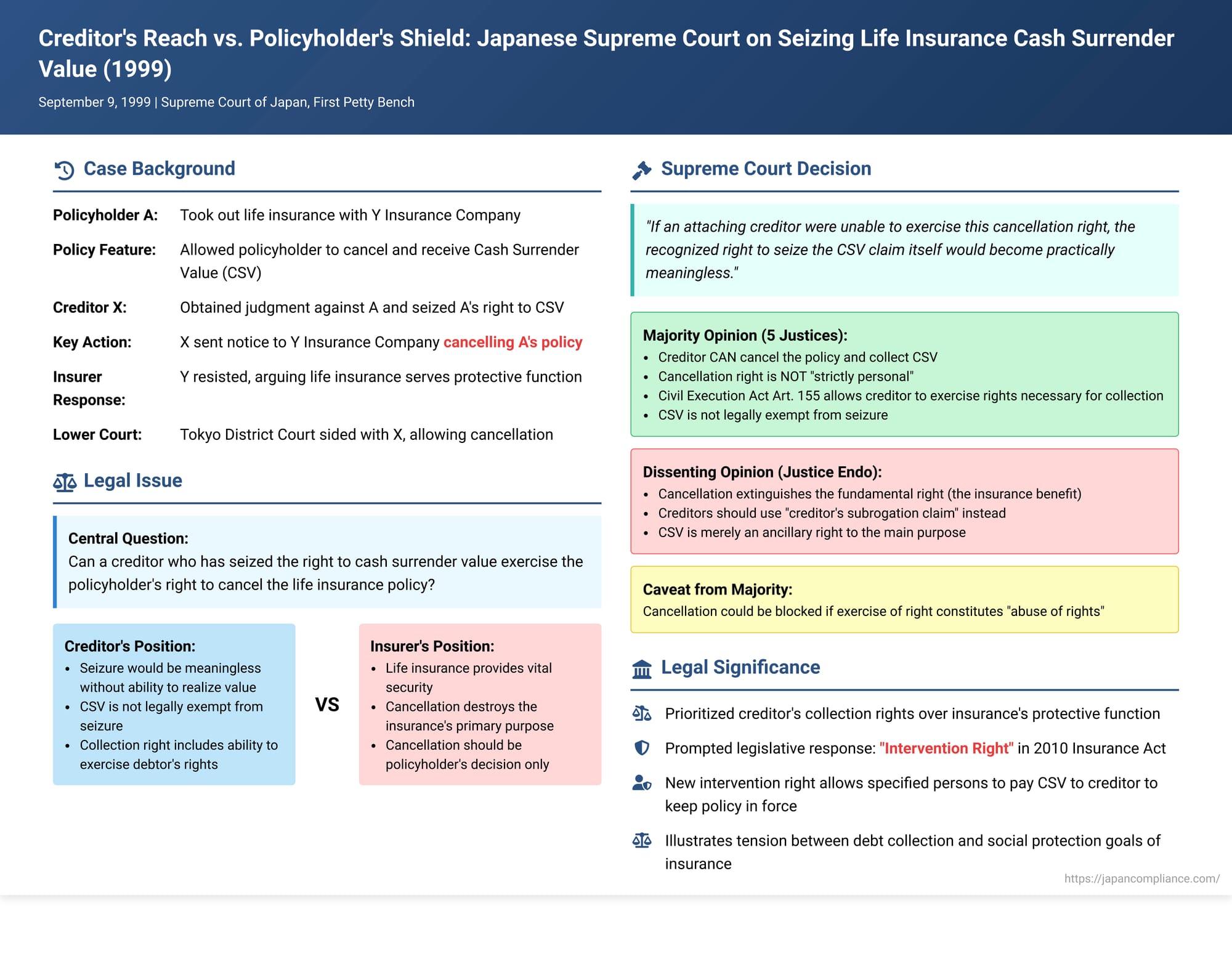

Life insurance policies often accumulate a cash surrender value (CSV), which the policyholder can access by canceling the policy. This CSV represents an asset, and like other assets, it can attract the attention of the policyholder's creditors. A crucial legal question then arises: can a creditor, having legally seized the policyholder's right to this CSV, then take the further step of forcing the cancellation of the life insurance policy to actually collect that value? This issue, pitting a creditor's right to recover a debt against the protective and personal nature of life insurance, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on September 9, 1999.

The Debtor, The Creditor, and The Insurance Policy: Facts of the Case

Mr. A was the policyholder of a life insurance contract with Y Life Insurance Company, where Mr. A himself was the insured. A key provision of this policy allowed Mr. A, as the policyholder, to cancel the contract at any time. Upon such cancellation, Y Insurance Company was obligated to pay a predetermined cash surrender value.

Mr. A had a creditor, X, who held a final court judgment confirming A's debt. To satisfy this debt, X obtained a seizure order from the court against A's right to claim the cash surrender value from Y Insurance Company. This formal seizure order was duly served on both Y Insurance Company (the third-party debtor in this context) and Mr. A (the original debtor).

After waiting for more than a week (a period relevant under Japan's Civil Execution Act, specifically Article 155, paragraph 1, concerning a creditor's right to collect), X took a decisive step. Based on its seizure of the CSV claim, X sent a formal notice to Y Insurance Company declaring its intention to cancel Mr. A's life insurance policy. This notice of cancellation was received by Y Insurance Company.

X subsequently filed a collection lawsuit against Y Insurance Company. X argued that as an attaching creditor, it had the right to exercise Mr. A's right to cancel the policy as part of its legally granted collection authority, thereby making the CSV payable. Y Insurance Company resisted this claim on several grounds. It argued that life insurance contracts serve a vital function in providing livelihood security for the insured and any death beneficiaries, and therefore, a creditor should not be able to unilaterally force their cancellation. Additionally, Y pointed out that Mr. A had taken out policy loans against the contract, and this outstanding loan amount should, in any event, be deducted from any payable CSV.

The Tokyo District Court, at the first instance, sided with X. It recognized the attaching creditor's right to exercise the policyholder's cancellation right and ordered Y to pay the CSV to X, after deducting the principal and interest of the outstanding policy loan. Both X and Y then agreed to waive their right to appeal to the High Court, and Y instead filed for a "leapfrog" appeal directly to the Supreme Court, a procedure permissible under specific conditions in Japanese civil procedure.

The Legal Standoff: Creditor's Collection Right vs. Nature of Life Insurance

The case presented several layered legal questions, though the primary one for the Supreme Court was the creditor's power to force cancellation:

- Seizure of Pre-Cancellation CSV Claim: Can a creditor even seize a policyholder's right to a cash surrender value before the policy has actually been cancelled? The general consensus in Japanese legal theory and lower court precedents was yes. The CSV claim, though conditional upon cancellation, is considered a specifiable property right and, unless specifically exempted by law (which life insurance CSV generally was not), it is subject to seizure. Both the majority and dissenting opinions in this Supreme Court case proceeded on the acceptance of this premise.

- Nature of the Cancellation Right: Is the policyholder's right to cancel their life insurance policy a "strictly personal right" (isshin senzoku-teki kenri)? Such rights, deeply tied to an individual's personal status or choices (like certain family law rights), cannot typically be exercised by third parties, including creditors. The prevailing view was that the right to cancel a life insurance policy does not fall into this category.

- Creditor's Exercise of Cancellation Right via Collection Authority: This was the core of the dispute. Assuming the CSV claim is seizable and the cancellation right isn't strictly personal, can the creditor, having seized the CSV claim, then actively exercise the debtor's cancellation right as part of the collection process outlined in Article 155 of the Civil Execution Act? Academic opinion was divided on this point, though some lower courts had affirmed this right.

The Supreme Court's Majority View: Creditor Can Cancel

The Supreme Court, by a majority decision, dismissed Y Insurance Company's appeal, thereby affirming the creditor X's right to cancel A's policy and collect the CSV.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Creditor's Collection Right: Article 155, paragraph 1, of the Civil Execution Act grants a creditor who has seized a monetary claim the right to collect that claim. The Supreme Court interpreted this collection right broadly, stating that it allows the attaching creditor to exercise, in their own name, all of the debtor's rights necessary for the collection of the seized claim, with the explicit exception of rights that are strictly personal to the debtor.

- Cancellation Right Not Strictly Personal: The Court found that the right to cancel a life insurance policy is different in nature from rights based on family law and that there were no compelling reasons why its exercise should be confined solely to the will of the policyholder. Therefore, it is not a strictly personal right.

- Cancellation as Essential for Collection: The right to the cash surrender value only comes into existence and becomes payable upon the condition that the policyholder (or someone empowered to act for them) exercises the right to cancel the policy. Thus, exercising the cancellation right is an indispensable act to make the seized CSV claim a tangible, collectible asset. The Court reasoned that if an attaching creditor were unable to exercise this cancellation right, the recognized right to seize the CSV claim itself would become practically meaningless. Therefore, exercising the cancellation right is an act properly within the scope and purpose of collecting the seized CSV claim.

- Life Insurance and Livelihood Protection: The Court acknowledged that life insurance contracts often serve as a means of livelihood protection for the debtor and their family, and that canceling a policy could lead to the debtor losing valuable benefits like potential severe disability coverage or hospitalization benefits. However, it pointed out that the CSV claim of a life insurance policy is not legally designated as an asset exempt from seizure, unlike certain other types of property specifically protected by law. The Court saw no compelling reason to treat CSV claims differently from other seizable assets that might also serve protective functions, such as bank deposits.

- Safeguards Against Abuse: While affirming the creditor's right to cancel, the majority opinion did note that this right is not entirely unfettered. It mentioned that if the seizure order itself were to be revoked (under Article 153 of the Civil Execution Act, which allows for cancellation or modification of execution measures under certain circumstances), or if the exercise of the cancellation right in a particular case amounted to an "abuse of rights," then the creditor's action might not be upheld.

The Dissenting Voice: Protecting the Policy's Core Purpose

Justice Endo Mitsuo issued a dissenting opinion, arguing that a creditor who has seized a CSV claim should not be permitted to exercise the cancellation right based solely on their collection authority under the Civil Execution Act.

His key arguments were:

- Conditional vs. Unconditional Rights: It is inappropriate to allow a creditor who has seized a conditional right (the CSV claim, which is conditional upon cancellation) to, by their own action of cancellation, transform it into an unconditional right to payment, thereby achieving the same effect as if they had seized an already existing, unconditional monetary claim.

- Ancillary vs. Fundamental Rights: The CSV claim is merely an ancillary right arising from the insurance contract. It is inappropriate for a creditor who has seized this ancillary right to be empowered to extinguish the fundamental right and purpose of the life insurance contract, which is the insurance benefit claim (e.g., death benefit) itself.

- Harm to Debtor's Expectations: Allowing creditors to unilaterally cancel policies could severely undermine the expectations and security that policyholders seek from life insurance.

- Alternative Creditor Remedy: Justice Endo argued that even without allowing cancellation via the collection right, the seizure of the CSV claim is not meaningless. Creditors could still potentially access the CSV by exercising the cancellation right through a different legal mechanism: a "creditor's subrogation claim" (saikensha dai-iken). This procedure, however, typically requires the creditor to prove the debtor's insolvency, offering a greater degree of protection to the debtor than the direct exercise of the cancellation right under the collection authority.

Unpacking the Implications and Debates

The Supreme Court's 1999 decision was significant in clarifying the power of creditors over a debtor's life insurance assets. It effectively prioritized a creditor's right to collect on a valid debt from non-exempt assets, even if that asset was tied to a life insurance policy.

- Balancing Interests: The majority opinion attempted to balance competing interests by allowing cancellation but acknowledging that principles like "abuse of rights" could act as a check. However, as legal commentators have noted, it might be practically difficult for an insurer (who is a third party to the creditor-debtor dispute) to successfully argue "abuse of rights" on behalf of the debtor, unless the circumstances are particularly extreme (e.g., forcing cancellation for a very small CSV relative to the debt, causing disproportionate harm).

- Criticism of "Collection Right" Approach: Those who opposed allowing cancellation via the collection right often emphasized the unique social and personal value of life insurance, arguing that its termination should not be lightly permitted, especially without the procedural safeguards of a creditor's subrogation claim, which requires demonstrating the debtor's insolvency. They feared that allowing easier cancellation could jeopardize the livelihood security that life insurance is intended to provide.

- Arguments Supporting the Court: Proponents of the Court's view stressed that life insurance CSV, not being a statutorily protected asset, should be treated like other seizable assets such as bank deposits, which also contribute to livelihood security. Furthermore, denying creditors the right to force cancellation would render the seizure of CSV claims largely ineffective, as the creditor would have to wait for the debtor to voluntarily cancel the policy, which might never happen. Also, a CSV claim is inherently precarious; if an insured event (like death) occurs before cancellation, the CSV claim typically disappears, replaced by the death benefit claim (payable to the beneficiary, not necessarily available to the policyholder's creditor).

The Evolution of Protection: The "Intervention Right" in the New Insurance Act

It is important to note that the legal landscape regarding this issue has evolved since the 1999 Supreme Court decision. The current Insurance Act of Japan (which came into full effect in 2010, replacing older Commercial Code provisions) introduced a significant new protection for policyholders and beneficiaries called the "intervention right" (kainyūken).

This intervention right (stipulated in Articles 60-62 for death benefit policies and Articles 89-91 for personal accident and fixed-benefit sickness/injury insurance) provides a mechanism for certain parties to prevent the forced cancellation of an insurance policy by a creditor. If an attaching creditor (or similar party) exercises a right to cancel a life insurance policy that has an accumulated premium reserve (which funds the CSV), the law now provides that the cancellation will only take effect one month after notice is given. During this one-month period, specified persons—typically relatives of the policyholder or insured, or an insured person who is also the beneficiary—can, with the policyholder's consent, pay the attaching creditor an amount equivalent to the CSV (as of the date the cancellation right was exercised) and notify the insurer of this payment. If these steps are taken, the creditor's cancellation is nullified, and the insurance policy remains in force.

This statutory intervention right offers a more structured and specific way to balance the legitimate interests of creditors with the desire to maintain valuable insurance coverage for the protection of policyholders and their families. It addresses some of the concerns raised by the dissent in the 1999 case by providing a clear path for beneficiaries to rescue a policy from forced cancellation by a creditor, provided they can compensate the creditor for the value of the seized CSV claim. In situations where the policyholder is aware that a creditor has seized the CSV and exercised the cancellation right, but the beneficiary (or other eligible person) does not exercise this intervention right, the insurer would likely proceed to pay the CSV to the creditor after the notice period, unless the cancellation is clearly an abuse of rights.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1999 decision gave considerable power to creditors seeking to recover debts from the cash surrender value of a debtor's life insurance policy, effectively treating CSV as a seizable asset akin to others like bank deposits, despite its role in livelihood protection. While the Court acknowledged the potential for hardship and pointed to general legal principles like "abuse of rights" as potential safeguards, the ruling leaned towards ensuring the efficacy of creditors' collection efforts. The subsequent enactment of the statutory "intervention right" in the Insurance Act reflects a legislative refinement of this balance, offering more specific and targeted protection to maintain insurance coverage when desired by those closely connected to the policy, while still acknowledging the creditor's claim to the policy's cash value.