Credit Card Debt in Bankruptcy: When Does "Malicious Intent" Make it Non-Dischargeable?

Date of Judgment: January 28, 2000 (Heisei 12)

Case Name: Claim for Damages (Main Action and Counterclaim)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

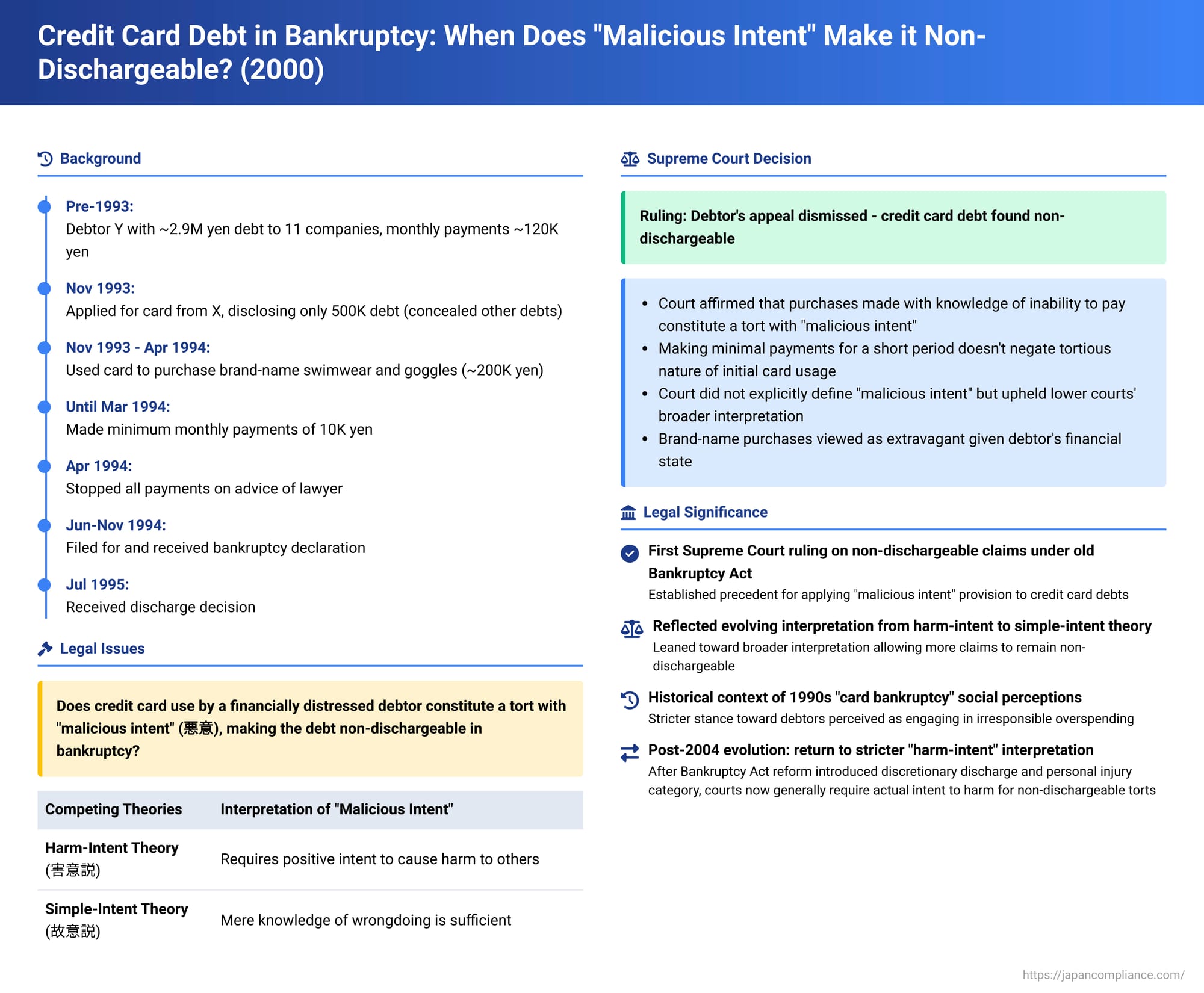

This blog post examines a 2000 Supreme Court of Japan decision concerning a common issue in personal bankruptcy: the dischargeability of debt accrued through credit card use when the cardholder was already financially distressed. The central legal question revolved around whether such credit card usage could be deemed a tort (wrongful act) committed with "malicious intent" (akui), which would render the resulting debt non-dischargeable under Japanese bankruptcy law.

Facts of the Case

The case focused on the main claim by X (plaintiff/appellee, a credit card company) against Y (defendant/appellant, the bankrupt cardholder). Y, born in 1952, divorced in 1986 and initially maintained her livelihood through financial assistance from her mother (200,000 yen/month) and income as an illustrator until around 1988. When her mother's aid ceased, she moved to an apartment with a monthly rent of about 30,000 yen and supported herself with her illustrator income and loans from banks and other sources. Around 1990, Y had defaulted on payments to another card company, A, and had returned that card.

In October 1993, upon a friend's recommendation, Y began working as a life insurance salesperson. She was told she could initially earn 150,000 yen per month, potentially rising to over 300,000 yen if she secured policies. However, her actual net monthly income was only about 130,000 yen. At that time, Y's debts totaled approximately 2.9 million yen from 11 companies, with monthly repayment obligations around 120,000 yen. She was also delinquent on national health insurance premiums since 1991.

In this financial state, on November 19, 1993, Y applied for a credit card (the "Card") from company X and a contract was concluded the same day. On her application, Y declared only a 500,000 yen debt to B Bank.

From the day the Card was issued until around April 1994, Y used the Card to purchase items such as brand-name competitive swimwear and goggles, totaling about 200,000 yen, for which X advanced payment. Y made monthly payments of 10,000 yen to X under a revolving payment plan until March 1994. However, from April 1994, following advice from a lawyer, she stopped payments to all her creditors.

On June 7, 1994, Y filed for bankruptcy. She quit her job as an insurance salesperson in August 1994, started a new job related to telegrams the following month, and on November 7, 1994, received a bankruptcy declaration and a decision for abolition of bankruptcy proceedings (due to lack of assets for distribution). Despite this, on December 22, 1994, X obtained a judgment against Y for the advanced sums. X did not object to Y's discharge application. Before Y was granted a discharge decision on July 4, 1995, X managed to garnish Y's salary, recovering just under 180,000 yen.

After Y obtained her discharge, X sued Y for damages. X alleged that Y, despite lacking the ability to pay, had obtained the Card, purchased goods, and had X advance the payments, constituting a tort. X claimed damages for the outstanding amount of the advanced payments and handling fees, totaling just over 110,000 yen.

Lower Court Rulings

The Tokyo District Court (court of first instance) found that Y's purchases using the Card were made under circumstances where default on the repayment obligation was clearly evident, and inferred that Y was fully aware that she would default. Thus, these purchases constituted a tort. The fact that Y made monthly installment payments of 10,000 yen until March 1994 did not negate this finding of tort. The court fully granted X's claim.

Y appealed. The Tokyo High Court largely affirmed the first instance court's reasoning, concluding that Y's purchases constituted a tort committed with "malicious intent" (akui) and dismissed Y's appeal. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal .

The Court's judgment was concise: "The original instance court's finding of facts regarding the points argued is affirmable in light of the evidence cited in the original judgment. Under these facts, the original instance court's determination that Y's purchases of the goods in question constituted a tort committed with malicious intent can be upheld. There is no illegality in the original judgment as argued. The appellant's arguments merely criticize the original instance court's discretionary weighing of evidence and findings of fact, advance a different view, or raise issues not argued in the original instance court, and thus cannot be adopted."

The Supreme Court, therefore, affirmed the lower courts' decisions without explicitly defining "malicious intent" or detailing its own analysis of the facts, effectively endorsing the conclusion that Y's conduct rendered the debt non-dischargeable.

Commentary and Elaboration

1. The System of Non-Dischargeable Claims and the Decision's Significance

Japanese bankruptcy law employs two mechanisms to reasonably limit the scope of a debtor's discharge:

- Grounds for Denying Discharge: The court examines whether any statutory grounds exist to deny discharge altogether (Bankruptcy Act Articles 250-252).

- Non-Dischargeable Claims: Even if a general discharge is granted, certain specific types of claims remain non-dischargeable, meaning the debtor is still liable for them (Bankruptcy Act Article 253, Paragraph 1).

The process first determines general eligibility for discharge, and then, if discharge is granted, its effect is tailored by excluding certain claims based on their nature.

This Supreme Court decision was the first by the highest court to rule on the applicability of non-dischargeable claim provisions, specifically concerning torts committed with "malicious intent" under the old Bankruptcy Act (pre-2004 reforms). As current bankruptcy and discharge rules have undergone some changes, the implications of this judgment must be understood within a broader context, including discussions on the granting or denial of discharge itself.

2. Credit Card Transactions and "Card Bankruptcy"

This case is a typical example of "card bankruptcy," where excessive credit card use leads to a member's insolvency.

- Basic Mechanism: A card company issues a card to a member. The member can use the card to purchase goods or services from affiliated merchants. The merchant sends sales slips to the card company and receives payment, usually less a merchant fee. The card company later collects the amount from the member. Often, if a member cannot pay the full amount by the due date (typically the following month), revolving credit plans allow them to make partial payments over time, with interest accruing on the outstanding balance, up to a certain credit limit. The revolving payments in this case were an example of such a plan.

- Underlying Premise and Risks: This system hinges on the member's ability to pay. Card companies conduct credit screening for applicants. However, screening is not foolproof, and a member's financial situation can deteriorate after a card is issued. The time lag in identifying such deterioration means defaults can occur. Card companies may factor a certain rate of default into their fee structures and still remain profitable. However, this can lead to a situation where the costs of misuse are dispersed (e.g., through higher merchant fees), potentially weakening incentives to prevent such misuse. Furthermore, if interest income from members unable to make full payments becomes a significant revenue source, it might even encourage card issuance to less creditworthy individuals. Card bankruptcy is one manifestation of these systemic issues.

3. Culpability in Card Bankruptcy and Social Context

- The societal perception of bankruptcy and discharge has evolved. In the 1980s, Japan faced a crisis with "sarakin" (loan sharks), whose high-interest loans and aggressive collection tactics led to tragic consequences like debtors absconding or committing suicide. Bankruptcy discharge gained social acceptance as a vital remedy in that context.

- In contrast, "card bankruptcies" of the 1990s were sometimes viewed more critically. Interest rates were generally not as high as those of loan sharks, and collection methods were less harsh. There was a perception, influenced by the "bubble economy" of the late 1980s, that many debtors, particularly younger people, had engaged in irresponsible overspending. This raised questions about the necessity of granting them relief through bankruptcy discharge.

- Two legal elements often underpinned criticism of card bankruptcies:

- Culpable Bankruptcy: Under the old Bankruptcy Act (Article 375, Item 1), causing significant depletion of assets or incurring excessive debt through extravagance could constitute the crime of "culpable bankruptcy" (katai hasan). Such conduct was also a ground for denying discharge (old Bankruptcy Act Article 366-9, Item 1). This was interpreted according to prevailing social norms; thus, purchasing expensive non-essential items on credit and accumulating debt could be seen as culpable by the then-majority who primarily used cash.

- Fraud: In the 1980s, several lower court rulings established that if a person used their own credit card to purchase goods without the ability or intent to pay the amount due, this could constitute fraud under Penal Code Article 246, Paragraph 1 (deceiving the merchant and fraudulently obtaining the goods). Based on these precedents, a card user lacking funds could readily be labeled a fraudster.

4. The Interpretation of "Malicious Intent" (akui) and the Supreme Court's Stance

- The direct legal issue in this case was the interpretation of "malicious intent" (akui) under Article 366-12, Item 2 of the old Bankruptcy Act (which corresponds to Article 253, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the current Act, making claims for damages from torts committed by the bankrupt with akui non-dischargeable). There was a doctrinal conflict:

- Harm-Intent Theory (害意説 - gai-i-setsu): Did akui require a positive intent to cause harm to others?

- Simple-Intent/Knowledge Theory (故意説 - koi-setsu): Or was mere knowledge of wrongdoing or simple intent (akin to general tortious intent) sufficient?

- The older prevailing view favored the harm-intent theory, aiming to limit non-dischargeable tort claims to situations involving clear personal culpability of the bankrupt.

- However, before the 2004 Bankruptcy Act reforms, the simple-intent/knowledge theory was gaining prominence. This shift had multiple drivers:

- One was a comparison with the U.S. Federal Bankruptcy Code, which specifically listed as non-dischargeable not only claims for willful and malicious injury but also, for example, certain claims for death or personal injury caused by the debtor's operation of a motor vehicle while intoxicated. The old Japanese law lacked an explicit provision for the latter, leading to attempts to cover such situations through a broader interpretation of akui.

- Another was the perceived need for balance with the grounds for denying discharge outright. A card bankruptcy like Y's could potentially be viewed as obtaining credit by fraudulent means (a ground for discharge denial, see current Bankruptcy Act Article 252, Paragraph 1, Item 5). If the same conduct was grounds for both denial of discharge and non-dischargeability of the specific debt, the differing severity of these outcomes (total denial vs. specific debt remaining) suggested a need for nuanced interpretation. Some argued for a stricter interpretation of grounds for denial of discharge, coupled with a more lenient (broader) interpretation of what makes a debt non-dischargeable.

- The Supreme Court in this 2000 judgment, while upholding the lower courts' conclusions (which were more aligned with the simple-intent/knowledge theory), did not explicitly define akui or provide its own detailed interpretation. This was similar to prior lower court rulings.

- The facts emphasized by the lower courts in Y's case included the purchase of brand-name swimwear (suggesting extravagance and thus culpability by contemporary standards) and Y's objectively dire financial situation (including a prior card default with company A, which made her continued card usage particularly questionable). Her making small revolving payments for a short period was deemed insufficient to negate the initially wrongful nature of her card usage.

- The commentary also notes that X's (the card company's) credit assessment of Y was arguably lenient. However, at that time, credit information bureaus in Japan were often segregated by industry, and information sharing was not comprehensive. This made it difficult for creditors to conduct thorough credit checks, leaving them somewhat reliant on the applicant's disclosures and good faith.

- Relevance Today: It's questionable whether similar card usage today would automatically be deemed tortious. Significant reforms, including the Money Lending Business Act amendment in 2006 and the Installment Sales Act amendment in 2008, led to the establishment of designated credit information bureaus and mandated their use by lenders during credit assessment. These changes likely reduce the scope for a credit provider to claim they were deceived solely by a debtor's partial non-disclosure of existing debts, if the provider did not make proper use of available credit information.

5. Developments After This Judgment (Post-2004 Bankruptcy Act Reforms)

The enactment of the new Bankruptcy Act in 2004 altered several premises underlying the 2000 decision and the surrounding debates:

- The definition of "culpable bankruptcy" as a crime was revised, and the term "extravagance" (rōhi) was removed from bankruptcy crime provisions. However, significant asset reduction through extravagance remains a ground for denying discharge (Bankruptcy Act Article 252, Paragraph 1, Item 4).

- Crucially, the new Act explicitly introduced the possibility of "discretionary discharge" (Bankruptcy Act Article 252, Paragraph 2). This allows courts to grant discharge even if grounds for denial exist, considering all circumstances. Current practice often leans towards granting discharge unless the misconduct is particularly severe, whether it's obtaining credit by fraudulent means (Item 5) or extravagance (Item 4).

- A new category of non-dischargeable claim was added: claims for damages arising from torts committed by the bankrupt that intentionally or through gross negligence caused harm to another person's life or body (Bankruptcy Act Article 253, Paragraph 1, Item 3).

- Following the 2000 Supreme Court decision and these legislative changes, there has been a renewed trend in lower court precedents to explicitly adopt the stricter harm-intent theory (gai-i-setsu) for "malicious torts" under Article 253, Paragraph 1, Item 2. The creation of the separate category for personal injury/death claims (Item 3) has removed one of the original arguments for a broader interpretation of "malicious intent" in Item 2. The increased availability of discretionary discharge also supports this trend; if discharge can be granted flexibly even with some misconduct, there is less need to rely on a broad interpretation of non-dischargeable claims to achieve a just outcome. Consequently, the harm-intent theory for Item 2 is arguably becoming the prevailing view again.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2000 decision affirmed that, under the specific facts presented, a bankrupt individual's continued use of a credit card despite clear inability to pay could constitute a tort committed with "malicious intent," rendering the debt to the card company non-dischargeable. While the Court did not explicitly define "malicious intent," its ruling came at a time when the interpretation of this term was evolving. Subsequent legislative reforms and judicial trends, particularly the introduction of discretionary discharge and a specific category for personal injury torts, have led to a resurgence of a stricter interpretation of "malicious intent" (requiring an intent to harm) for general torts to be deemed non-dischargeable. This case highlights the dynamic interplay between societal views on debt, debtor culpability, and the evolving framework of bankruptcy law aimed at balancing debtor rehabilitation with creditor protection.