Court's Own Fact-Finding in Japanese Administrative Cases: A Power, Not a Duty

Judgment Date: December 24, 1953

Case Number: Showa 24 (O) No. 333 – Claim for Revocation of Administrative Appeal Decision

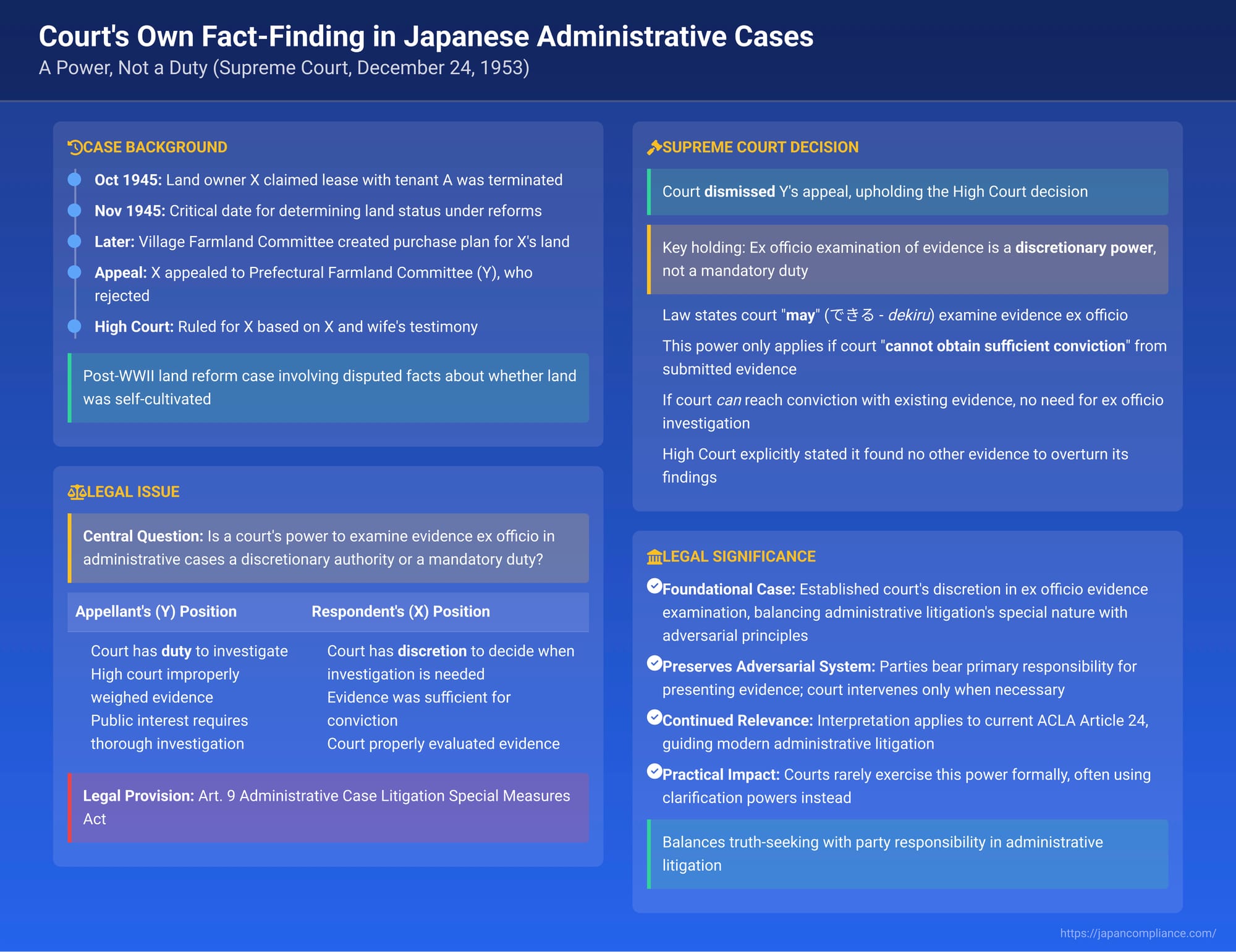

In legal systems based on the adversarial principle, courts typically rely on the parties involved in a lawsuit to present evidence and build their respective cases. However, Japanese administrative litigation has a provision that allows courts to examine evidence on their own initiative (ex officio). A key question addressed by the Supreme Court in a 1953 land reform case was whether this power constitutes an obligation for the court or remains a discretionary tool.

The Land Reform Dispute: Conflicting Testimonies

The case originated from the post-World War II land reforms in Japan. X (the Plaintiff, Segawa Ichisuke) was a landowner whose fields had been leased to a tenant, A. X claimed that he and A had mutually agreed to terminate the lease at the end of October 1945, and X had taken back the land for self-cultivation.

Despite this, the local B Village Farmland Committee subsequently established a compulsory purchase plan for X's fields, apparently deeming X an absentee landlord and the land eligible for redistribution under the land reform laws. X filed an administrative appeal against this purchase plan with the Iwate Prefectural Farmland Committee (the Defendant, Y). Y rejected X's appeal. The written decision of this rejection was later referred to in court as Exhibit Ko No. 1.

X then sued in court to have Y's rejection decision revoked. The Sendai High Court (second instance) ruled in favor of X. It found that as of the critical date for determining land status under the reforms (November 23, 1945), X was indeed cultivating the land himself, meaning the lease with A had been terminated prior to this date. The High Court based this finding on the testimony of X and X's wife, while discounting conflicting testimony from the chairman and secretary of the B Village Farmland Committee.

Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court. Among Y's arguments were:

- The High Court had improperly weighed the evidence, giving undue credence to the testimony of X and his wife (who had a direct interest in the outcome) over the testimony of the Farmland Committee officials (who Y argued were more neutral and responsible parties).

- The High Court had dismissed Exhibit Ko No. 1 (the Prefectural Farmland Committee's own appeal rejection decision, which presumably contained findings unfavorable to X) without providing adequate reasons, thereby violating empirical rules of evidence assessment.

- Crucially, Y argued that Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Special Measures Act (ACSLSMA)—the law then governing such lawsuits and a precursor to Article 24 of the current Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA)—empowered the court to examine evidence ex officio (on its own initiative). Y contended that given the significant public interest involved in land reform, the High Court had a legal duty to exercise this power to thoroughly investigate the facts and reach a firm conviction, especially when it was choosing to reject the official findings. Y claimed the High Court's failure to do so was an illegal omission.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (December 24, 1953): Ex Officio Examination is Discretionary

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the High Court's decision. The most significant part of its reasoning concerned the nature of the court's power to examine evidence ex officio.

The Court addressed Y's argument that the High Court's failure to conduct an ex officio investigation under ACSLSMA Article 9 was unlawful. It noted that:

- The High Court had considered Exhibit Ko No. 1 but had ultimately set it aside, explicitly stating in its judgment that "there is no other evidence sufficient to overturn the aforementioned finding" (i.e., the finding that X was owner-cultivating the land).

- Y's contention essentially amounted to a criticism of the High Court's discretionary evaluation and weighing of the evidence presented.

- ACSLSMA Article 9 stipulated that the court may (できる - dekiru) examine evidence ex officio if, from the evidence already submitted, it cannot obtain a sufficient conviction (shōko ni tsuki jūbun no shinshō o erarenai baai) regarding the facts.

- The Supreme Court clarified that if the court is able to obtain a sufficient conviction based on the evidence presented by the parties, then there is no necessity for it to further examine evidence on its own initiative.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Y's arguments regarding the High Court's handling of evidence and its alleged failure to conduct an ex officio investigation were without merit.

Significance of the Ruling

This 1953 decision is a foundational case in Japanese administrative law for several reasons:

- Discretionary Power, Not a Duty: It established that the court's power to examine evidence ex officio in administrative lawsuits is a discretionary authority, not a mandatory obligation. The court can choose to exercise this power, but it is not required to do so if it feels confident in its findings based on the evidence already before it.

- Preserving Adversarial Principles: While acknowledging the special nature of administrative cases (which often involve public interest and an imbalance of information between the state and individuals), this ruling preserves the fundamental adversarial nature of court proceedings. Parties bear the primary responsibility for presenting their evidence, and the court intervenes with its ex officio powers mainly when the presented evidence is insufficient for it to reach a clear understanding.

- Continuing Relevance: Although decided under the old ACSLSMA, this interpretation remains highly relevant for Article 24 of the current ACLA, which contains a similar provision for ex officio examination of evidence (though the explicit reference to "maintaining public welfare" as a condition was removed in the ACLA). Legal commentary confirms this as a leading case on the subject.

The Role of Ex Officio Examination in Practice

Legal commentary provides further context on how this power operates:

- Relationship to the Adversarial Principle (弁論主義 - Benron Shugi): Japanese administrative litigation, through Article 7 of the ACLA, generally adopts the adversarial principle from civil procedure, where parties present facts and evidence. Article 24 ACLA serves as a specific exception, allowing the court a more active role in evidence gathering, reflecting the public interest often inherent in administrative disputes and the potential for an "inequality of arms" between citizen plaintiffs and the well-resourced state.

- Distinction from Full Ex Officio Fact-Finding (職権探知主義 - Shokken Tanchi Shugi): It's crucial to understand that Article 24 ACLA (and its predecessor, ACSLSMA Article 9) authorizes the ex officio examination of evidence primarily concerning facts already alleged or put into contention by the parties. It generally does not grant the court full shokken tanchi powers, which would involve the court independently searching for and introducing entirely new facts not raised by any party. Full inquisitorial fact-finding was a characteristic of Japan's pre-war administrative courts but is not a general feature of the post-war judicial system, barring specific statutory provisions in certain fields (e.g., family law).

- Actual Usage in Court: In practice, courts rarely make formal use of their power under ACLA Article 24 to directly call for evidence ex officio. Instead, the function of clarifying ambiguities or prompting further evidence is often achieved through the court's power to seek clarification (釈明権 - shakumeiken) from the parties, a tool available under the Code of Civil Procedure (Article 149).

- Addressing "Inequality of Arms": While the ex officio examination power is sometimes seen as a means to address the informational imbalance between individuals and the state, other legal mechanisms also contribute to this goal. For instance, rules concerning orders for document production have been debated and, in general civil procedure, expanded. Furthermore, the 2004 ACLA amendments introduced Article 23-2, which provides a special clarification procedure, allowing courts to request the administrative agency (even one not a party to the suit) to submit materials that clarify the reasons for a disposition or records from an administrative review. This aims to enhance the fullness and speed of trials by facilitating earlier clarification of disputes and evidence. This is distinct from ex officio evidence gathering under Article 24 but serves a complementary purpose.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1953 Supreme Court decision in this land reform case provides an enduring interpretation of the court's role in evidence gathering within Japanese administrative litigation. While empowered to take the initiative in examining evidence when necessary to form a clear conviction, the court is not under an obligation to do so if it can confidently decide the case based on the materials and arguments presented by the litigants. This approach seeks to balance the court's duty to ascertain the truth with the fundamental responsibility of the parties to build and present their own cases, allowing for judicial intervention to ensure fairness and clarity without fully supplanting the adversarial nature of the proceedings.