Corroboration of Confessions in Japanese Law: The 1967 Unlicensed Driving Case

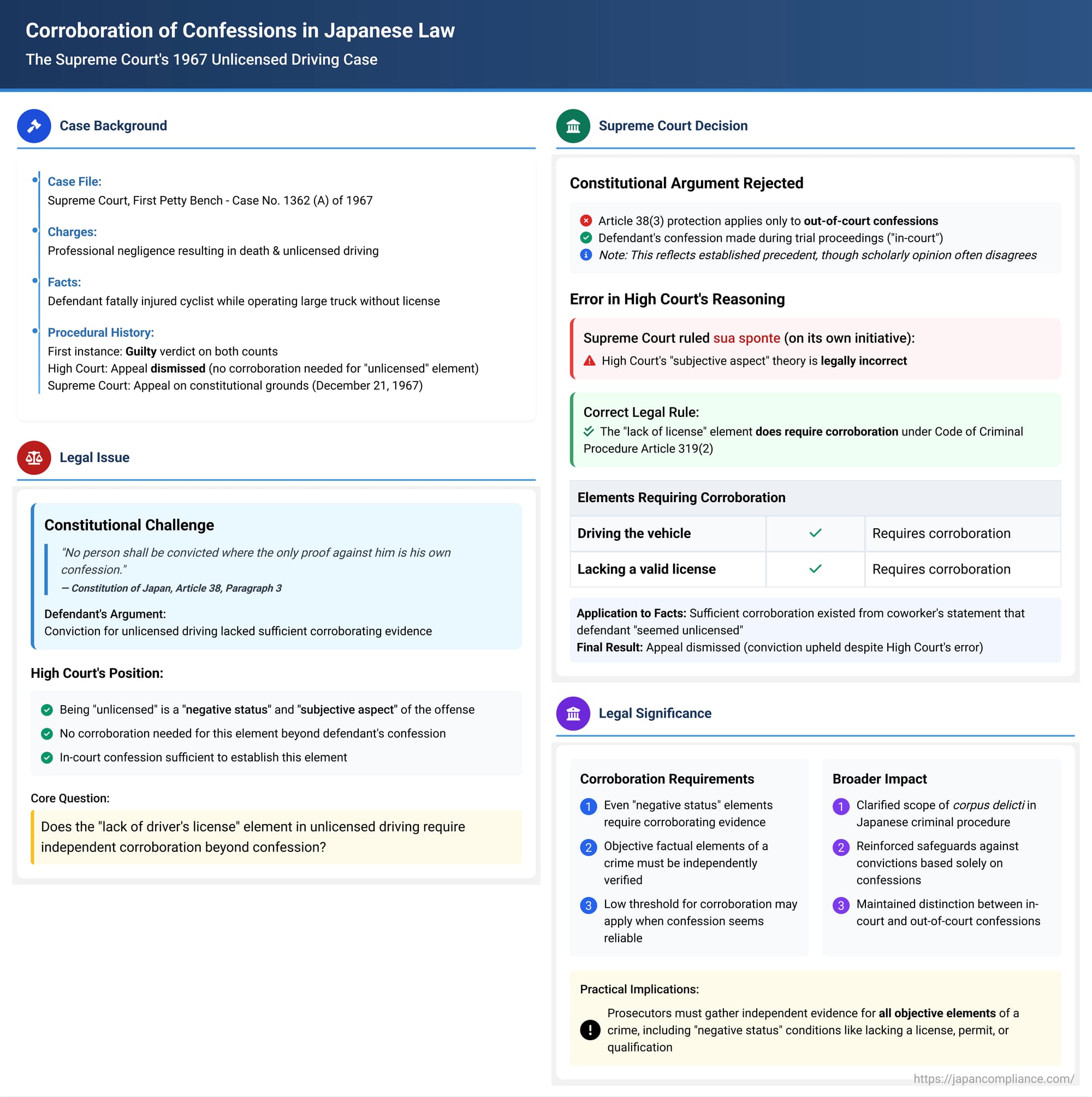

On December 21, 1967, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment (Case No. 1362 (A) of 1967) concerning a case of professional negligence resulting in death and violation of the Road Traffic Act, specifically driving without a license. While ultimately upholding the conviction, the court took the opportunity to clarify an important point regarding the corroboration required for confessions, particularly concerning the element of lacking a driver's license.

Background of the Case

The defendant, I. Y., was charged with fatally injuring a cyclist while negligently operating a large truck (professional negligence resulting in death) and, concurrently, with driving that truck without a valid driver's license, a violation of the Road Traffic Act.

The first instance court found the defendant guilty on both counts and sentenced him to imprisonment. The defendant appealed, arguing, among other points, that the finding of unlicensed driving lacked sufficient corroborating evidence and the judgment was therefore flawed.

The High Court dismissed the appeal. Regarding the unlicensed driving charge, it reasoned that being "unlicensed" represented a "negative status" and its subjective aspect could be established solely based on the defendant's own confession, particularly since the defendant had confessed to being unlicensed throughout the trial proceedings in the first instance court. Thus, the High Court concluded that no separate corroborating evidence was necessary for this specific element of the offense.

The defendant further appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily arguing a violation of Article 38, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution of Japan.

Constitutional Argument Regarding Confessions

Article 38, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution stipulates: "No person shall be convicted where the only proof against him is his own confession." This provision, along with Article 319, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, establishes the principle that a confession alone is insufficient for a conviction; independent corroborating evidence is required. This rule, often referred to as the "corroboration rule," serves as a crucial safeguard against wrongful convictions based on false or coerced confessions, acting as an exception to the principle of free evaluation of evidence. It aims to prevent miscarriages of justice that might arise if courts place undue weight on confessions, potentially overlooking their unreliability. It also implicitly encourages investigators to seek objective evidence beyond securing a confession.

The defendant argued that his conviction violated this constitutional protection. However, the Supreme Court swiftly dismissed this argument, citing established precedent from its own Grand Bench decisions. These precedents clarify that the term "his own confession" in Article 38, Paragraph 3 refers specifically to confessions made outside the courtroom (e.g., during police interrogation). Confessions made by the defendant in open court during the trial are not considered to fall under the scope of this constitutional restriction. Since the defendant I. Y. had confessed to the charges in the first instance court proceedings, the constitutional argument was deemed inapplicable.

It is worth noting, however, that while this remains the established legal precedent, many legal scholars argue that the distinction between in-court and out-of-court confessions lacks a strong theoretical basis, as interrogation influences can extend into the courtroom, and even voluntary confessions may be false. Therefore, many scholars contend that the constitutional requirement for corroboration should apply equally to in-court confessions.

The Supreme Court's Clarification on Corroboration for Unlicensed Driving

Despite rejecting the main constitutional appeal point, the Supreme Court addressed, sua sponte (on its own initiative), the High Court's reasoning regarding the unlicensed driving charge and the need for corroboration under Article 319, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The High Court had suggested that the "negative status" of being unlicensed was a "subjective aspect" provable by confession alone. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected this interpretation. It ruled that for the crime of unlicensed driving, corroborating evidence is required not only for the physical act of driving the vehicle but also for the factual element of the defendant not possessing a valid driver's license at the time. A confession alone is insufficient to prove this lack of license; independent evidence confirming this fact is necessary.

This finding aligns with the prevailing interpretation of the corroboration rule, which generally requires corroboration for the objective elements of a crime (the corpus delicti, or the essential facts showing a crime occurred), while often deeming corroboration unnecessary for purely subjective elements like intent (e.g., malice aforethought in murder) or knowledge (e.g., knowing goods are stolen in receiving stolen property cases). The fact of lacking a license, while describing a status, is an objective factual condition essential to the crime of unlicensed driving, distinct from the driver's mental state. The court determined it requires independent verification beyond the defendant's admission.

Application to the Facts and Final Decision

Although the Supreme Court found that the High Court had misinterpreted Article 319, Paragraph 2 by stating that the lack of a license required no corroboration beyond the confession, this legal error did not ultimately affect the outcome of the appeal.

The Supreme Court noted that the record contained sufficient corroborating evidence. Specifically, the first instance judgment referenced a statement given by M. S., a coworker of the defendant, to a judicial police officer. In this statement, the coworker indicated that, based on their working relationship, he believed the defendant did not possess a driver's license. The Supreme Court deemed this coworker's statement sufficient to corroborate the defendant's own in-court confession about being unlicensed.

Therefore, while the High Court's legal reasoning on the specific point of corroboration for the "unlicensed" element was flawed, the conviction itself was supported by both the defendant's in-court confession and the coworker's statement serving as adequate corroboration. Consequently, the error in legal interpretation did not impact the final judgment, and the Supreme Court dismissed the defendant's appeal.

Commentary suggests that while the coworker's statement ("doesn't seem to have a license") might seem somewhat speculative or weak as corroboration, its acceptance by the court might be understood in the context of the defendant having confessed in open court and not actively disputing the fact of being unlicensed. This potentially reflects the "relative theory" often seen in precedent, where the required strength of corroboration can vary depending on the perceived reliability of the confession itself.

Conclusion

The 1967 Supreme Court decision in the case of I. Y. is significant for its clarification regarding the application of the confession corroboration rule under the Code of Criminal Procedure. It firmly established that the objective fact of lacking a driver's license in an unlicensed driving charge requires independent corroborating evidence beyond the defendant's confession, rejecting the notion that such a "negative status" is merely a subjective element exempt from this rule. While upholding the established (though academically debated) principle that in-court confessions fall outside the scope of Article 38, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution, the ruling underscored the importance of objective verification for core factual elements constituting a crime, even when admitted by the defendant.