Supreme Court Narrows Correction Rights over Medical Receipts – Kyoto City Case (Japan, 2006)

TL;DR

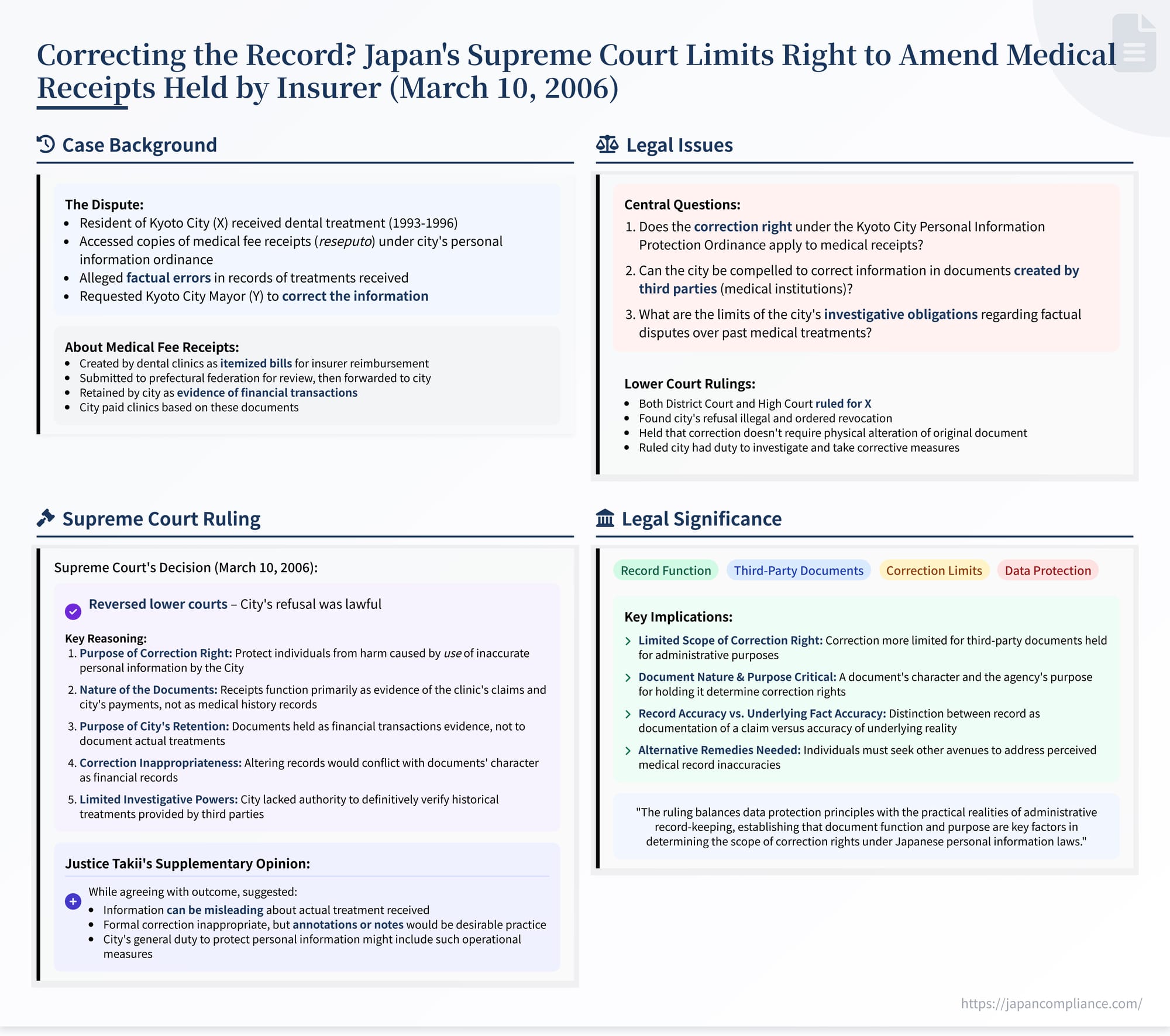

Japan’s Supreme Court (Mar 10 2006) held that an insured person cannot compel Kyoto City to “correct” dental treatment details on National Health Insurance receipts because the city keeps those receipts solely as financial evidence, not as medical records. The ruling clarifies the narrow scope of data‑correction rights where information originates from third parties and is retained for bookkeeping purposes.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Disputed Dental Records and a Correction Request

- The Ordinance and Lower Court Rulings

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (March 10 2006)

- The Supplementary Opinion

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On March 10, 2006, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the scope of an individual's right to request correction of personal information held by public bodies (Case No. 2001 (Gyo-Hi) No. 289, "Personal Information Non-Correction Decision Revocation Case"). The case specifically addressed whether an individual insured under the National Health Insurance system could compel the municipal insurer (Kyoto City) to correct alleged factual inaccuracies regarding dental treatments recorded on medical fee receipts (reseputo) that originated from the treating clinics. The Court ultimately ruled that the city's refusal to correct the information was lawful, drawing important distinctions based on the nature of the document, the purpose for which the city held the information, and the intended scope of the correction right under the applicable local data protection ordinance. This analysis explores the case's background, the legal framework under the Kyoto City ordinance, and the Supreme Court's reasoning and its implications.

Factual Background: Disputed Dental Records and a Correction Request

The appellee, X, an individual residing in Kyoto City, utilized the access rights granted under the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance (hereinafter "the Ordinance," referring to the version pre-dating later national harmonization) to obtain copies of National Health Insurance medical fee receipts (reseputo - レセプト) related to dental treatments received between October 1993 and February 1996. These receipts detail the services provided and associated fees, forming the basis for reimbursement claims by medical providers.

Upon reviewing the disclosed receipts, X believed that the information recorded concerning the dental treatments actually received contained factual errors. Asserting these inaccuracies, X submitted a formal request to the implementing agency under the Ordinance – the appellant, Y (the Mayor of Kyoto City, representing the municipal government) – demanding correction of the allegedly erroneous personal information contained within the receipts, pursuant to Article 21, Paragraph 1 of the Ordinance.

On May 30, 1997, Y issued a decision refusing X's correction request (hereinafter "the Disposition"). The stated reasons for the refusal were twofold: first, that Kyoto City, as the insurer holding the receipts, lacked the legal authority to alter or correct these specific documents (which originated from the dental clinics), and second, that the Mayor (Y) lacked the authority to conduct the investigation necessary to verify X's claims about the actual treatment received.

Understanding the Medical Fee Receipt (Resepto): It's crucial to understand the nature and lifecycle of the resepto in this context:

- Origin: The receipts were created by the dental clinics that treated X. They served as itemized bills submitted by the clinics to claim reimbursement from the insurer (Kyoto City) for the costs of medical care provided under the National Health Insurance system.

- Submission and Review: The clinics submitted these receipts, attached to a claim form, not directly to the City, but to the Kyoto Prefectural National Health Insurance Federation ("the Federation"). The Federation, acting under delegation from the City, reviewed these claims for compliance with insurance rules and fee schedules.

- Payment and Retention by the City: After the Federation's review, the receipts were forwarded to the City. The City then paid the approved reimbursement amounts to the clinics via the Federation. Subsequently, the City retained the resepto documents. From the City's perspective, these receipts served primarily as evidentiary documents supporting its financial expenditures – proof of payment for the claimed medical services.

The Ordinance and Lower Court Rulings

The legal battle centered on the interpretation of the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance, which aimed to protect individuals' rights regarding their personal data held by city agencies. Key relevant provisions included:

- Definition of Personal Information: Information related to an individual by which the individual is or can be identified (Art. 2(1)).

- Right of Access: Individuals had the right to request disclosure of their personal information held by implementing agencies (Art. 18(1)).

- Right to Request Correction: An individual who received disclosure and believed there was a factual error in the content of their personal information could request the implementing agency to correct it (Art. 21(1)).

- Agency's Duty: Upon receiving a correction request, the agency must conduct necessary investigations and decide whether to make the correction within 30 days (Art. 23(1)).

Lower Court Decisions: X challenged Y's refusal in court. Both the first instance court (Kyoto District Court) and the appellate court (Osaka High Court) ruled in favor of X, finding the City's refusal illegal and ordering its revocation. The High Court, in particular, reasoned that:

- The purpose of the correction request under the Ordinance was to clarify factual errors concerning the individual.

- The Ordinance established a right to demand corrective measures to achieve this clarification, which did not necessarily require physically altering the original document itself (e.g., annotations could suffice).

- The implementing agency (Y) had a duty under the Ordinance to investigate the alleged error and take appropriate corrective measures if an error was confirmed.

- This duty existed regardless of whether the City possessed the authority to directly modify the original resepto document created by the clinic. Y could not refuse correction solely on the grounds of lacking authority over the original document or investigation.

Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 10, 2006)

The Supreme Court, delivering its judgment on March 10, 2006, disagreed with the lower courts' interpretation and ultimately overturned their rulings, dismissing X's original claim. The Court meticulously analyzed the purpose of the correction right in relation to the specific nature and context of the resepto documents held by the City.

1. Purpose of the Correction Right:

The Court began by affirming the fundamental purpose of the correction request system under the Ordinance: to protect individuals' rights and interests from potential harm caused by the use of inaccurate personal information managed by the City.

2. Nature and Purpose of the Held Information:

The Court then emphasized the specific characteristics of the resepto information as held by the City:

- The resepto was created by a third party (the medical institution) as a claim for reimbursement, detailing the treatment the institution asserted it performed.

- The City acquired these documents after review by the Federation and subsequent payment.

- The City's primary purpose for retaining the resepto was as evidence of financial transactions – supporting documentation for its income and expenditure records related to paying the claimed medical fees.

3. Correction Inconsistent with Document's Character:

Given this context, the Court reasoned that demanding the City (as the implementing agency) correct the content of the treatment recorded on the resepto based on allegations that the actual treatment differed would be inappropriate. Such correction would fundamentally conflict with the document's character as a record of the clinic's claim and the basis upon which the City made its payment. Altering this record would misrepresent the transaction the City was documenting.

4. Limited Relevance to Individual Rights & Use Limitation:

The Court further noted that under the Ordinance (Art. 8(1)), personal information collected by an agency should generally be managed and used only within the scope necessary to achieve the administrative purpose for which it was collected. Given the City's purpose for holding the resepto (financial record-keeping), the information recorded about X's treatment was not, at the time of the correction request, being managed by the City for the direct purpose of reflecting the actual medical treatment X received. Therefore, the Court found it difficult to conclude that the information, as held and used by the City, directly pertained to X's rights and interests in a way that would trigger the Ordinance's correction mechanism.

5. Limited Investigative Powers:

The Court also pointed to the practical limitations on the implementing agency's (Y's) investigative powers. While the Ordinance required necessary investigation, it did not grant Y special powers to compel information or conduct inquiries externally, particularly concerning the verification of historical medical treatments performed by third-party clinics. The inherent limits on Y's ability to definitively establish the "true facts" of past treatment were a relevant consideration.

6. Correction Not Envisioned by the Ordinance:

Considering all these points – the fundamental nature of the resepto as a third-party claim document held as a financial record, the City's specific purpose for holding it, the limited direct impact on X's rights in that context, and the practical limits on investigation – the Supreme Court concluded that the Ordinance's correction request system was not intended to apply to this type of situation. Correcting the substantive medical details recorded on these receipts was deemed outside the scope envisioned by the Ordinance's correction mechanism.

Conclusion on Legality: Consequently, the Supreme Court held that Y's decision to refuse X's correction request (the Disposition) was not illegal under the Ordinance.

The Supplementary Opinion

A supplementary opinion was added by one Justice, agreeing with the outcome but offering slightly nuanced reasoning.

- This opinion emphasized that the direct meaning of the information on the resepto is the fact that the clinic submitted a claim for reimbursement based on the listed treatments. In this narrow sense, the record of the claim itself contains no factual error.

- However, it acknowledged that this information strongly suggests or implies that the individual actually received the listed treatments. In this respect, the information can be misleading and potentially constitute incorrect information about the individual. This was the basis of X's request.

- While conceding the information qualified as "personal information" under the Ordinance, this opinion agreed that "correction" (in the sense of altering the record to reflect the "true" treatment) was inappropriate given the document's nature as a claim record. It found no basis in the Ordinance to compel such alteration.

- It also found no clear basis in the Ordinance to compel alternative "corrective measures" (like annotation) for documents that are not inherently inaccurate as records of a claim, even if they contain potentially misleading personal information.

- Crucially, however, the supplementary opinion suggested that public bodies like the City, under their general duty to take necessary measures to protect personal information (Ordinance Art. 3(1)), should consider taking practical steps when faced with claims of factual inaccuracy in the personal information contained within such third-party documents. It proposed that "appropriate measures, such as adding a note to the document... so that it will be known if the information is used thereafter," would be a desirable operational practice to mitigate potential harm from misleading information, even if not legally mandated as a "correction" under Article 21.

Implications and Significance

This 2006 Supreme Court decision provides important clarification on the boundaries of the right to request correction of personal information held by public entities in Japan, particularly concerning records originating from third parties.

- Scope of Correction Right Limited: The ruling significantly limits the scope of the correction right when applied to documents created by third parties and held by a public body primarily for documenting its own transactions or administrative processes (like payment verification and financial record-keeping). It suggests that the right primarily targets inaccuracies in information generated by or directly reflecting the actions or status determined by the holding agency itself.

- Nature and Purpose of Document is Key: The decision underscores the importance of considering the specific nature of the document and the purpose for which the public body holds the information when assessing a correction request. Correction is less likely to be mandated if it conflicts with the document's essential character or the agency's holding purpose.

- Distinction Between Record Accuracy and Underlying Fact Accuracy: The case highlights a critical distinction: the accuracy of a record as a record of a specific event (e.g., a claim being made) versus the accuracy of the information contained within that record concerning an underlying reality (e.g., the actual treatment provided). The correction right under the ordinance, in this context, was found not to extend to forcing the holder of the claim record to adjudicate and alter its record based on disputes about the underlying reality.

- Practical Challenges for Individuals: For individuals seeking to correct perceived errors in medical records reflected in insurance claims held by insurers, this ruling indicates that the data protection correction request route may be ineffective for altering the substance of the treatment recorded on the original claim document held by the insurer. Alternative avenues (e.g., directly addressing the medical provider, separate legal actions if financial harm resulted) might be necessary.

- Relevance to National Law: While this case dealt with a local Kyoto ordinance, the principles discussed regarding the purpose of correction rights, the nature of third-party documents, use limitations, and investigative powers are relevant to interpreting similar provisions in Japan's national Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), especially as it applies to public sector bodies after recent amendments aimed at harmonization.

- Importance of Annotation/Operational Measures: The supplementary opinion, while not binding law, points towards a recommended best practice: even if formal correction isn't mandated, agencies holding potentially misleading third-party information should consider operational measures like annotation to prevent future misuse and protect individual rights, aligning with their broader data protection duties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 10, 2006 judgment concluded that under the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance, an individual could not compel the City, acting as the insurer, to correct alleged factual errors concerning medical treatments recorded on medical fee receipts (reseputo) submitted by the treating clinics. This decision was based on the nature of the resepto as primarily a claim document and financial record in the hands of the City, the City's specific purpose for holding it, and the interpretation that the Ordinance's correction mechanism did not extend to altering such third-party records to reflect disputed underlying facts. While denying the right to compel correction in this specific context, the ruling, particularly through the supplementary opinion, acknowledged the potential for such records to be misleading and hinted at the desirability of alternative administrative measures to mitigate potential harm.