Correcting Tax Credit Errors: Japanese Supreme Court on 'Declaration Requirements' and Reassessment Requests in the Minami Kyushu Case

Date of Judgment: July 10, 2009

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Disposition of No Reason to Make Reassessment (平成19年(行ヒ)第28号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

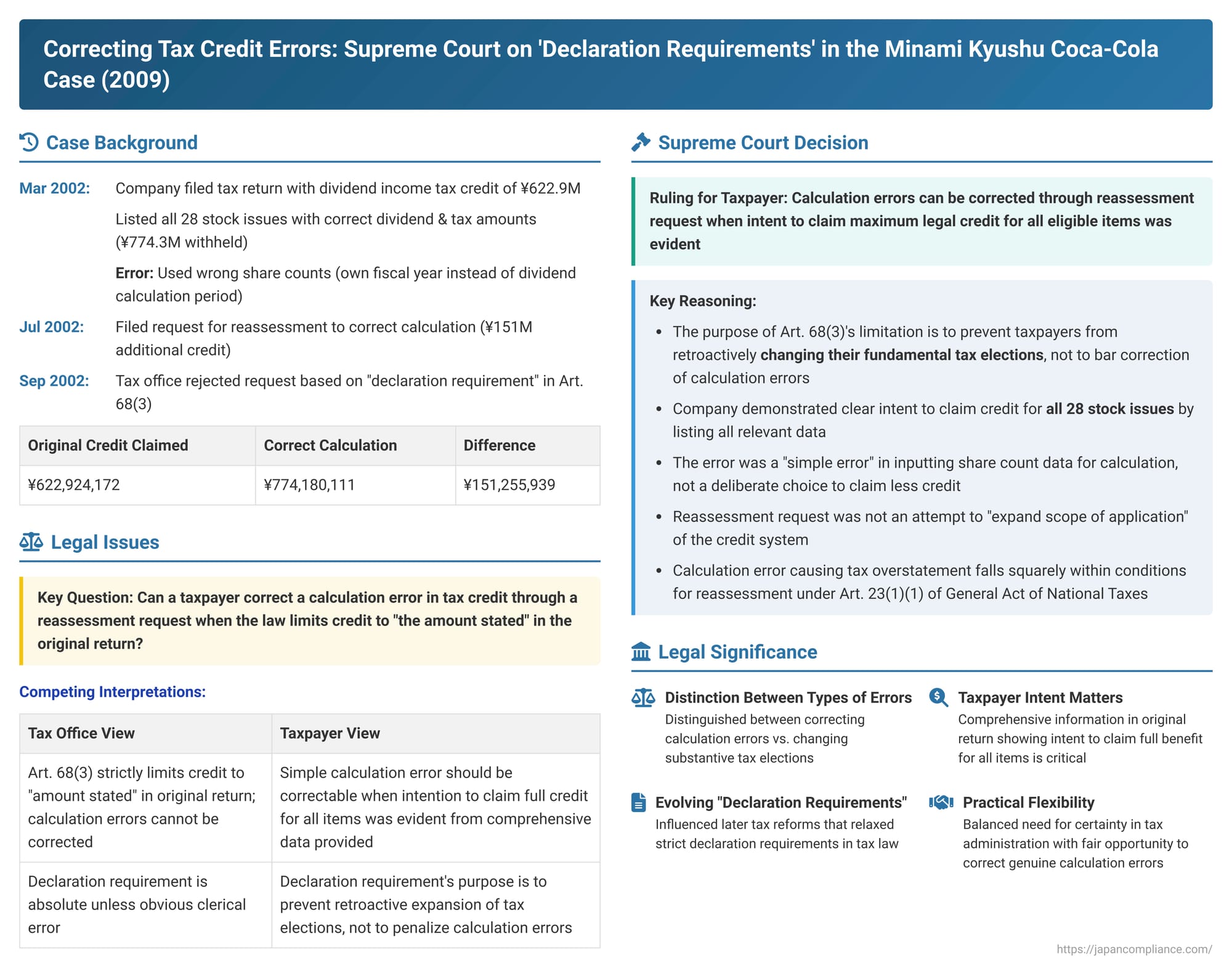

In a significant decision on July 10, 2009, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified the extent to which a taxpayer could correct errors made in claiming tax credits on an original tax return. The case centered on whether a company that had clearly intended to claim the full, legally permissible income tax credit for taxes withheld on dividends—and had provided all necessary underlying data to that effect—but made a simple calculation error resulting in an under-claimed credit amount, was barred from correcting this error through a "request for reassessment" (更正の請求 - kōsei no seikyū) due to restrictive wording in the then-applicable tax law. The Court ultimately sided with the taxpayer, emphasizing the difference between correcting a calculation error and attempting to retroactively change a fundamental tax election.

The Dividend Tax Credit and a Costly Miscalculation

The appellant, X , was a company engaged in the manufacturing and sale of soft drinks. For its corporate income tax return for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2001 ("the subject fiscal year"), filed on March 29, 2002, X sought to apply the income tax credit available under Article 68, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act (CTA). This credit allows a domestic corporation to deduct from its corporate tax liability the amount of income tax that was withheld at source on dividends and similar distributions it received during the year, thus preventing double taxation of the same income stream at the corporate level.

To calculate the creditable amount, X utilized a method known as the "simplified method by issue" (銘柄別簡便法 - meigarabetu kanben hō), as prescribed by Article 140-2, paragraph 3 of the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order (the version prior to a 2006 amendment). In the schedule attached to its tax return (Schedule 6(1), "Detailed Statement on Income Tax Credit"), X meticulously listed all 28 stock issues it owned from which it had received dividends. For each of these 28 issues, X correctly stated the total amount of dividends received (totaling approximately ¥3.87 billion) and the total amount of income tax withheld at source on those dividends (totaling approximately ¥774.3 million).

However, a critical error occurred in applying the simplified method. This method required inputting the number of shares held at the beginning and end of the dividend calculation period of the respective dividend-paying companies (which was generally the calendar year 2000). Instead, X mistakenly entered the number of shares it held at the beginning and end of its own fiscal year (the subject fiscal year, ending December 2001). This error in the share count data for 8 out of the 28 stock issues led to an incorrect calculation of the allocable income tax credit under the simplified method. As a result, X claimed an income tax credit of ¥622,924,172 in its original return, whereas the correctly calculated creditable amount, based on the data it had otherwise accurately provided, should have been ¥774,180,111. This was an under-claim of approximately ¥151 million.

Upon discovering this error, X, on July 10, 2002, filed a "request for reassessment" with the head of the competent tax office, Y, pursuant to Article 23, paragraph 1, item 1 of the General Act of National Taxes. This provision allows taxpayers to request a correction if the tax base or tax amount stated in their return was not in accordance with tax laws or if there was an error in the calculation. X sought to claim the correct, higher credit amount and thereby reduce its corporate tax liability.

The tax office (Y) rejected X's request, issuing a notice on September 25, 2002, stating that there was "no reason to make a reassessment" ("the subject notice disposition"). Y's primary argument was based on Article 68, paragraph 3 of the Corporate Tax Act (the version applicable at the time). This paragraph stipulated that the income tax credit under paragraph 1 would only apply if the tax return included a statement of the amount to be credited and details of its calculation, and critically, that "the amount to be credited under the provisions of paragraph 1 shall be limited to the amount stated as such amount" in the return. Y contended that this provision strictly limited X to the ¥622.9 million originally declared, regardless of the error.

Subsequently, Y issued a corrective assessment to X for the subject fiscal year on an entirely separate matter. X then amended its lawsuit to seek cancellation of this new reassessment to the extent that it failed to incorporate the corrected, higher income tax credit X had claimed in its request for reassessment. The Fukuoka High Court ruled against X on the income tax credit issue, interpreting CTA Article 68(3) strictly and finding that a mere calculation error did not generally warrant a reassessment request unless there were exceptional circumstances like obvious clerical errors or unavoidable reasons for the mistake, which it deemed not present in X's case. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Wrangle: Strict Wording vs. Evident Intent

The core legal issue before the Supreme Court was whether the restrictive wording of Article 68, paragraph 3 of the Corporate Tax Act (old version)—limiting the income tax credit to "the amount stated as such amount" in the originally filed tax return—prevented a taxpayer from correcting a clear calculation error through a request for reassessment, especially when the taxpayer's overall intention to claim the maximum legally allowable credit for all eligible income items was evident from the comprehensive data provided in the original return and its accompanying schedules. The High Court had favored a strict interpretation of the limitation, while X argued for the right to correct a manifest error.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Intent and Nature of Error Prevail

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision on this point and ruled in favor of X, concluding that X was entitled to correct the calculation error and claim the full, correctly calculated income tax credit through its request for reassessment.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose of the Income Tax Credit (CTA Article 68(1)): The Court began by reaffirming the purpose of the income tax credit for domestic corporations: it is to eliminate the double taxation that would otherwise occur when corporate income is taxed first as income of the dividend-paying company, then again when income tax is withheld at source from the dividends paid to the recipient corporation, and finally when those dividends are included in the recipient corporation's income for corporate tax purposes.

- Interpreting the "Declaration Requirement" in CTA Article 68(3) (Old Version): The Court then carefully analyzed the intent behind the limiting language in Article 68(3). This provision required the tax return to state the amount claimed for credit and details of its calculation, and limited the creditable amount to that "stated as such amount." The Court interpreted the primary purpose of this limitation not as an absolute bar to correcting any and all errors, but rather as a rule to prevent a taxpayer who, in their original return, had made a conscious choice not to apply the income tax credit for all or part of their eligible withheld tax, from later reversing that substantive election and seeking to retroactively expand the scope of application of the credit system through a request for reassessment. In essence, it was about the finality of the taxpayer's initial choice or election regarding which income items to subject to the credit mechanism, not necessarily about uncorrectable minor errors in calculating the amount once that choice was made for all eligible items.

- X's Evident Intent in the Original Return: The Supreme Court found that X's original tax return, particularly the attached Schedule 6(1) ("Detailed Statement on Income Tax Credit"), provided clear evidence of X's intentions. By listing all 28 stock issues it owned, the total dividends received from each of these issues, and the total amount of income tax that had been withheld on those dividends for each specific issue, X had demonstrated an unambiguous intent to apply the income tax credit system to the entirety of the income tax withheld on dividends from all of its eligible stockholdings. The Court inferred that X's intention was to claim the full, correctly calculated amount based on the comprehensive data presented.

- Nature of the Error: The mistake made by X was a "simple error" (tanjun na ayamari) in inputting the incorrect share numbers (using its own fiscal year-end/start numbers instead of the dividend calculation period numbers) into the formula for the simplified method of calculation for some of the stock issues. There were no circumstances suggesting that X had deliberately chosen to claim a lesser amount of credit for any specific reason or that it intended to exclude certain dividends from the credit calculation. The error was within the mechanical process of calculation, not a fundamental choice to forego a portion of the credit.

- Reassessment Request Was Not an Improper Expansion of Choice: Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that X's request for reassessment was not an attempt to "additionally expand the scope of application" of the income tax credit system in a way that Article 68(3) was designed to prevent. X was not trying to change its mind about which dividends to claim credit for; rather, it was seeking to correct a calculation error within the framework of its clearly manifested original intent to claim the full available credit for all eligible dividends.

- Qualification for Reassessment Request: Therefore, the fact that X had under-declared the creditable amount due to this calculation error, which in turn resulted in an overstatement of its corporate tax liability, clearly fell under the conditions permitting a request for reassessment as stipulated in Article 23, paragraph 1, item 1 of the General Act of National Taxes (i.e., "the calculation of the tax base, etc., or tax amount, etc., stated in the return was not in accordance with the provisions of national tax laws, or there was an error in the said calculation"). The tax office's refusal to allow this correction was, therefore, illegal.

Key Principles and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision in the case is a significant precedent in Japanese tax procedure, particularly concerning the correction of errors in tax returns that involve specific declaration requirements:

- Distinction Between Correction of Calculation Errors and Change of Taxpayer Election: This is the central takeaway from the ruling. The Court drew a crucial distinction:

- If a taxpayer demonstrates a clear intent in their original return to apply a beneficial tax provision to all eligible items and provides all necessary data, a subsequent request to correct a mere calculation error that led to an under-claim of that benefit is generally permissible through a request for reassessment.

- This is different from a taxpayer attempting to retroactively change a fundamental choice or election made in the original return (e.g., deciding to now claim a credit they had initially chosen not to claim for certain income items, or wishing to switch from one mutually exclusive tax accounting method to another after the fact). Such changes in election are more likely to be barred by restrictive "declaration requirement" provisions like the old Article 68(3).

- Importance of Comprehensive Information in Original Return: The fact that X had meticulously listed all 28 stock issues and provided the full details of dividends received and tax withheld for each was instrumental in the Supreme Court's ability to infer X's clear intention to claim the maximum legally allowable credit for all those items. This comprehensive disclosure supported the argument that the under-claim was a mere calculation error, not a deliberate choice to partially waive the credit.

- Evolution of "Declaration Requirements" in Tax Law: "Declaration requirements" (当初申告要件 - tōsho shinkoku yōken), which mandate that certain tax benefits or treatments must be explicitly claimed or elected in the original tax return to be valid, have historically been a feature of Japanese tax law, sometimes leading to harsh outcomes for inadvertent omissions or errors. This Supreme Court ruling provided a more taxpayer-favorable interpretation in cases involving clear calculation errors within an otherwise evident intent to claim a benefit. It is important to note that many such strict declaration requirements in the Corporate Tax Act and other tax laws were subsequently relaxed or abolished in later tax reforms (e.g., the 2011 tax reform). For instance, the current version of Corporate Tax Act Article 68, paragraph 4 explicitly allows the income tax credit to be claimed not only in the original tax return but also in an amended return or a request for reassessment, making the specific issue litigated in this case largely moot for the income tax credit itself today. However, the principles established regarding the interpretation of such declaration requirements and the critical distinction between correcting errors versus impermissibly changing past elections remain relevant for other tax provisions where similar requirements might still exist.

- Refining Earlier Precedents: This case can be seen as refining or distinguishing earlier, potentially stricter, Supreme Court precedents. For example, a Showa 62 (1987) judgment had denied a taxpayer's request for reassessment when they sought to switch from an elected "estimated expense" method to an "actual expense" method for calculating medical practitioners' necessary expenses, after realizing the initial choice was less favorable. The current case is distinguishable because X was not trying to change the fundamental choice of applying the income tax credit system (its intent to do so for all items was clear), but rather to correct a mechanical error in the calculation of the amount under the chosen simplified method, within that overarching choice.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision in the case is an important landmark that underscores a degree of flexibility in correcting errors in Japanese tax returns, even when specific "declaration requirements" are in place. The ruling clarified that such requirements are primarily intended to prevent taxpayers from retroactively altering substantive tax elections, not to bar the correction of clear calculation errors when the taxpayer's original intent to claim the full, legally permissible benefit for all eligible items is evident from the comprehensive information provided in the filed return. This decision emphasizes the importance of discerning the taxpayer's true intent from the totality of their declaration and provides a pathway for rectifying genuine calculation mistakes through a request for reassessment.