Corporate Veil and Criminal Hands: When a Director's Crime Voids Company Life Insurance – A 2002 Japanese Supreme Court Case

Date of Judgment: October 3, 2002

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 310 (Ju) of 2002 (Insurance Claim Case)

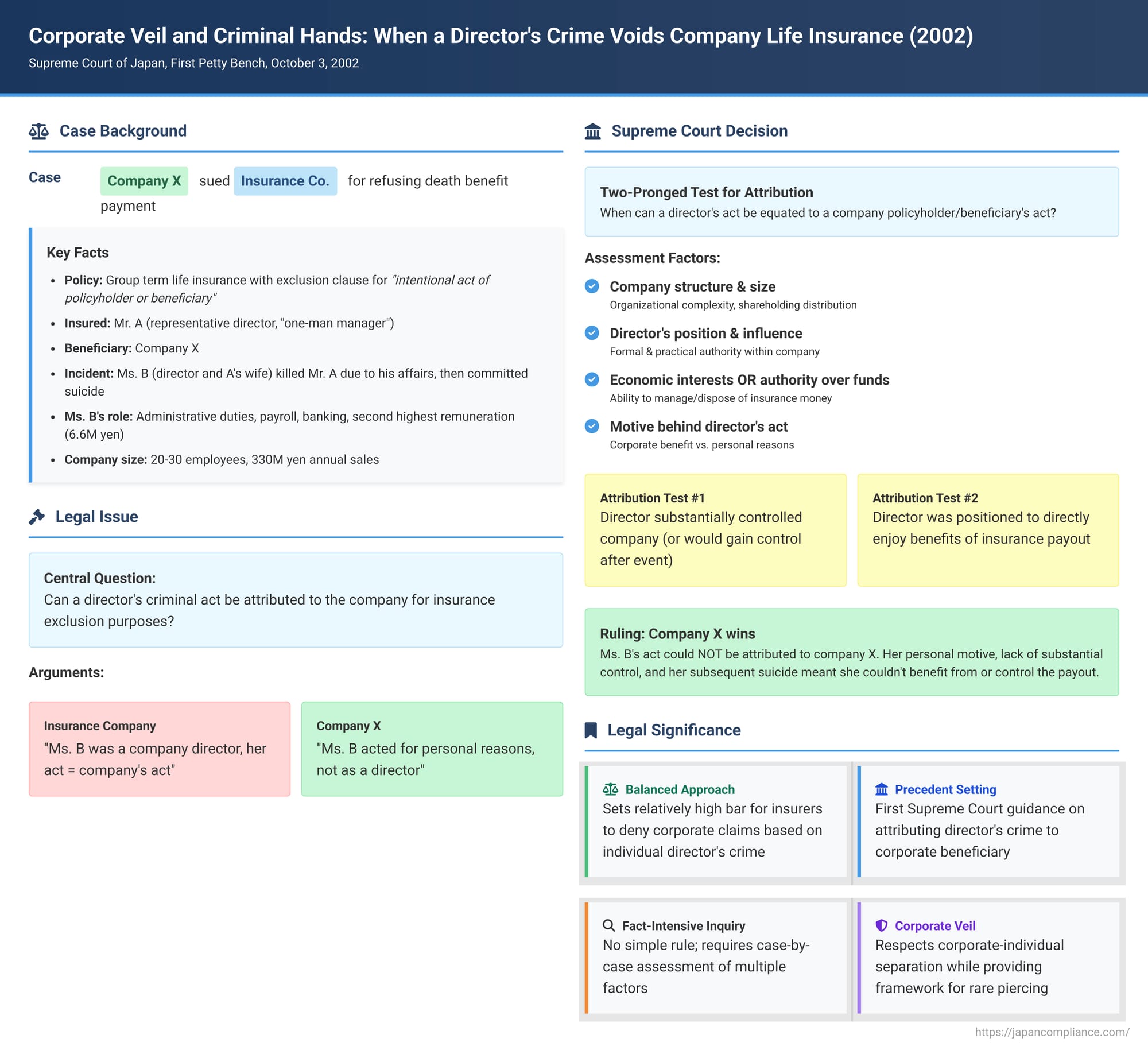

Life insurance policies taken out by companies on key personnel are a common business practice. These "key person" policies often name the company as the beneficiary, providing financial support in the event of the insured individual's death. However, a dark and complex legal question arises if a director or executive of that beneficiary company intentionally causes the death of the insured key person. Does the criminal act of an individual within the company trigger an exclusion clause that would otherwise void the policy payout to the company itself? This intricate issue was at the heart of a significant decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 3, 2002.

A Fatal Intersection of Business and Personal Tragedy: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff was a limited company, X (which later became a stock company), founded and largely managed by its representative director, Mr. A. Company X had entered into a group term life insurance contract with Y Insurance Company, the defendant. Under this policy, Mr. A was the insured, and company X was the designated beneficiary. The policy included a crucial exclusion clause: Y Insurance Company would not pay the death benefit if the insured (Mr. A) died as a result of the "intentional act of the policyholder or beneficiary" (i.e., company X).

The tragedy unfolded when Mr. A's wife, Ms. B, intentionally killed Mr. A by striking him on the head at their home. Mr. A died from a brain contusion resulting from the blow. Immediately after killing her husband, Ms. B committed suicide. The motive for Ms. B's actions was reportedly her distress over Mr. A's extramarital affairs.

Complicating the insurance matter was Ms. B's role within company X. At the time of the incident, the directors of company X were Mr. A (the representative director, described as a "one-man manager" who dominated most of the company's operations), Ms. B herself, their eldest son C, and Mr. A's younger brother D. Ms. B's involvement in X was primarily administrative; she handled tasks like employee payroll, social insurance paperwork, and was one of two people (along with A) who held a key to the company safe containing important documents like bill books, company seals, and title deeds. She also engaged with banks for loan rollovers, drew bills for financing, and accompanied Mr. A to the tax accountant's office during fiscal closings. However, her role was characterized as auxiliary to Mr. A's overall management, and she was not involved in the core business of securing or executing construction contracts.

Financially, company X had annual sales of around 330 million yen in the mid-1990s and employed 20 to 30 people, including those in affiliated companies. Its total capital was 15 million yen. Mr. A held the largest share (8.2 million yen), while Ms. B and Mr. D each held 1.6 million yen, and C held 1 million yen. In terms of remuneration for the fiscal year 1996, Mr. A received 11.4 million yen, Ms. B received 6.6 million yen (the second highest), Mr. D received 5.64 million yen, and Mr. C received 2.66 million yen.

Company X filed a claim for the disaster death benefit under the policy (120 million yen). Y Insurance Company refused to pay, asserting that Ms. B's intentional killing of Mr. A fell under the exclusion clause, as Ms. B was a director of X, the beneficiary company. Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of company X, compelling Y Insurance Company to pay. The insurer then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Challenge: Attributing a Director's Personal Crime to the Company

The pivotal legal question was whether Ms. B's act of killing Mr. A could be attributed to company X, thereby triggering the exclusion clause that nullified payment if the insured was killed by the "intentional act of the policyholder or beneficiary." This required the Court to determine the circumstances under which the personal criminal act of a director could be identified with the company itself for the purposes of such an insurance exclusion.

The Supreme Court's Two-Pronged Test for Attribution

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed Y Insurance Company's appeal, meaning company X was entitled to the insurance payout. In its reasoning, the majority laid out a general framework for when a director's intentional act of killing an insured can be equated to an act by the company policyholder/beneficiary.

The Court began by noting that the exclusion clause in question was similar in intent to provisions in the old Commercial Code (Article 680, paragraph 1, items 2 and 3), which dealt with intentional killing of the insured by the beneficiary or the policyholder. The fundamental purpose of such exclusions, the Court affirmed (citing its own 1967 precedent), is to prevent a situation where a policyholder or beneficiary could profit from the crime of murder. Allowing insurance payout in such cases would be contrary to public policy and the principle of good faith and fair dealing.

The Court stated that such an exclusion clause covers not only cases where the policyholder or beneficiary entity itself (as an abstract legal person) intentionally causes the insured event, but also extends to situations where a third party's intentional act can be equated to the act of the policyholder or beneficiary, when viewed in light of the exclusion clause's underlying purpose.

Specifically for cases where the policyholder or beneficiary is a company and one of its directors intentionally kills the insured, the Supreme Court established a two-pronged test. The director's act can be attributed to the company if a comprehensive assessment of various factors leads to the conclusion that the director's conduct should be treated as the company's conduct. These factors include:

- The company's size and organizational structure.

- The director's position and influence within the company at the time of the insured event.

- The commonality of economic interests between the director and the company, OR the director's authority to manage or dispose of the insurance money.

- The motive behind the director's act.

The Court then specified two particular situations where such attribution (equating the director's act with the company's) would occur:

- Substantial Control: The director substantially controlled the company, or was in a position to acquire such substantial control immediately after the insured event.

- Direct Enjoyment of Benefit: The director was in a position to directly enjoy the benefits flowing from the company's receipt of the insurance payout.

Applying the Test: Why Company X Still Got Paid

Applying this framework to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found that Ms. B's actions could not be equated to an act by company X:

- The Court noted company X's size (annual sales ~330 million yen, 20-30 employees) and the fact that Mr. A was the dominant "one-man manager." Ms. B, despite being a director and Mr. A's wife, held no representative authority and her role was primarily auxiliary, not managerial.

- Given Ms. B's personal motive (distress over Mr. A's affairs) and her immediate suicide after killing Mr. A, the Court concluded that she did not substantially control company X, nor was she in a position to gain such control after Mr. A's death.

- Similarly, she was not in a position to "directly enjoy" the insurance benefits that would be paid to company X.

- Therefore, the Court held that B's act, driven by personal motives, could not be deemed the act of company X for the purpose of the exclusion clause. The fact that Ms. B was involved in some financial administration, held a key to the safe, and received the second-highest director's remuneration did not alter this conclusion.

The Dissenting View: A Broader Interpretation of "Company Act"

Justice Fukazawa Takehisa issued a dissenting opinion. While agreeing with the general legal criteria set forth by the majority, he disagreed with their application to the specific facts of the case. Justice Fukazawa believed that Ms. B's actions should have been equated with an act by company X, thereby triggering the exclusion.

He emphasized the importance of considering public policy, the principle of good faith, and the requirement of the fortuity of the insured event. In his view, Ms. B's significant remuneration (second only to Mr. A and exceeding that of other directors), her possession of a company safe key, her role in financial matters (negotiating with banks, drawing bills), and the fact that her shareholding in the company would likely have become the largest after Mr. A's death (assuming she inherited his shares by statutory succession) all pointed to a strong commonality of economic interest with company X. He argued that these factors placed her in a position where she could have authority over the insurance money and directly benefit from its receipt, and potentially control the company after the event (he noted that the 1967 Supreme Court precedent held that even if a killer-beneficiary commits suicide without intent to personally acquire funds, the insurer is still exempt).

Unpacking the Test: "Substantial Control" and "Direct Enjoyment"

The Supreme Court's two main conditions for attributing a director's act to the company—"substantial control" and "direct enjoyment of benefit"—have been the subject of academic discussion.

The "direct enjoyment of benefit" prong likely means more than an indirect financial gain that any shareholder might experience if the company receives a large sum. It suggests a situation where the director and the company are so closely identified that the company's assets are, in effect, the director's personal assets, or where the director has the practical ability to appropriate or freely use the insurance money paid to the company.

The "substantial control" prong is perhaps more ambiguous. It could refer to a director who is the alter ego of the company, exercising pervasive operational control such that their actions are indistinguishable from the company's. Alternatively, it might mean control that allows the director to personally benefit from the insurance payout (linking it back to the "direct enjoyment" idea). The Court's inclusion of "or was in a position to... acquire such substantial control immediately after the insured event" is particularly debated, especially as some academic views suggest that if a director like a representative who concludes policies is to be identified with the company, their control at the time of the act should be paramount.

The role of the director's "motive" as a consideration is also complex. While the Court lists it, some scholars find it inconsistent with the principle established for natural person beneficiaries (as in the 1967 Supreme Court case) where the killer-beneficiary's motive for killing (e.g., not for insurance money) does not negate the exclusion. However, it's argued that determining whether a director's act can be equated to the company's act is a threshold question, distinct from whether motive should then be considered once attribution is established. If a director is effectively an owner-manager whose interests are identical to the company's, their motive for the killing might be irrelevant (the exclusion applies). But if the director's connection to the company is less absolute, their motive (e.g., killing the insured to benefit the company financially) might become a relevant factor in the initial determination of whether their act can be considered the company's act at all.

Significance and Ongoing Discussion

This 2002 Supreme Court decision was the first to provide comprehensive guidance from Japan's highest court on how to attribute a director's intentional killing of an insured person to the corporate policyholder/beneficiary for the purpose of an insurance exclusion clause.

The ruling establishes a fact-intensive inquiry, looking at a range of factors rather than a simple rule. This can lead to a degree of uncertainty in predicting outcomes, as the assessment involves a "comprehensive" consideration of "various circumstances."

The decision underscores the tension between recognizing the company as a legal entity separate from its directors and acknowledging that, in some situations, the actions of key individuals are so intertwined with the company's control or financial benefit that they must be deemed the company's own acts for the purpose of applying such exclusion clauses fairly.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court in this case set a relatively high bar for insurers seeking to deny claims to corporate beneficiaries based on the criminal act of one of the company's directors. The emphasis on whether the director had "substantial control" over the company or stood to "directly enjoy the benefits" of the insurance payout means that if the wrongdoing director's motives were purely personal and their ability to dominate the company or personally access the insurance funds was limited, the company itself may still be entitled to the policy proceeds. This decision highlights the judiciary's careful approach to balancing the prevention of unjust enrichment through crime against the legitimate claims of a corporate entity that may itself be a victim of, or at least not culpably involved in, the director's wrongdoing.