Corporate Tenant, New Management: Does it Void the Lease? A Japanese Supreme Court Answer

Date of Judgment: October 14, 1996

Case Name: Building Removal and Land Surrender Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

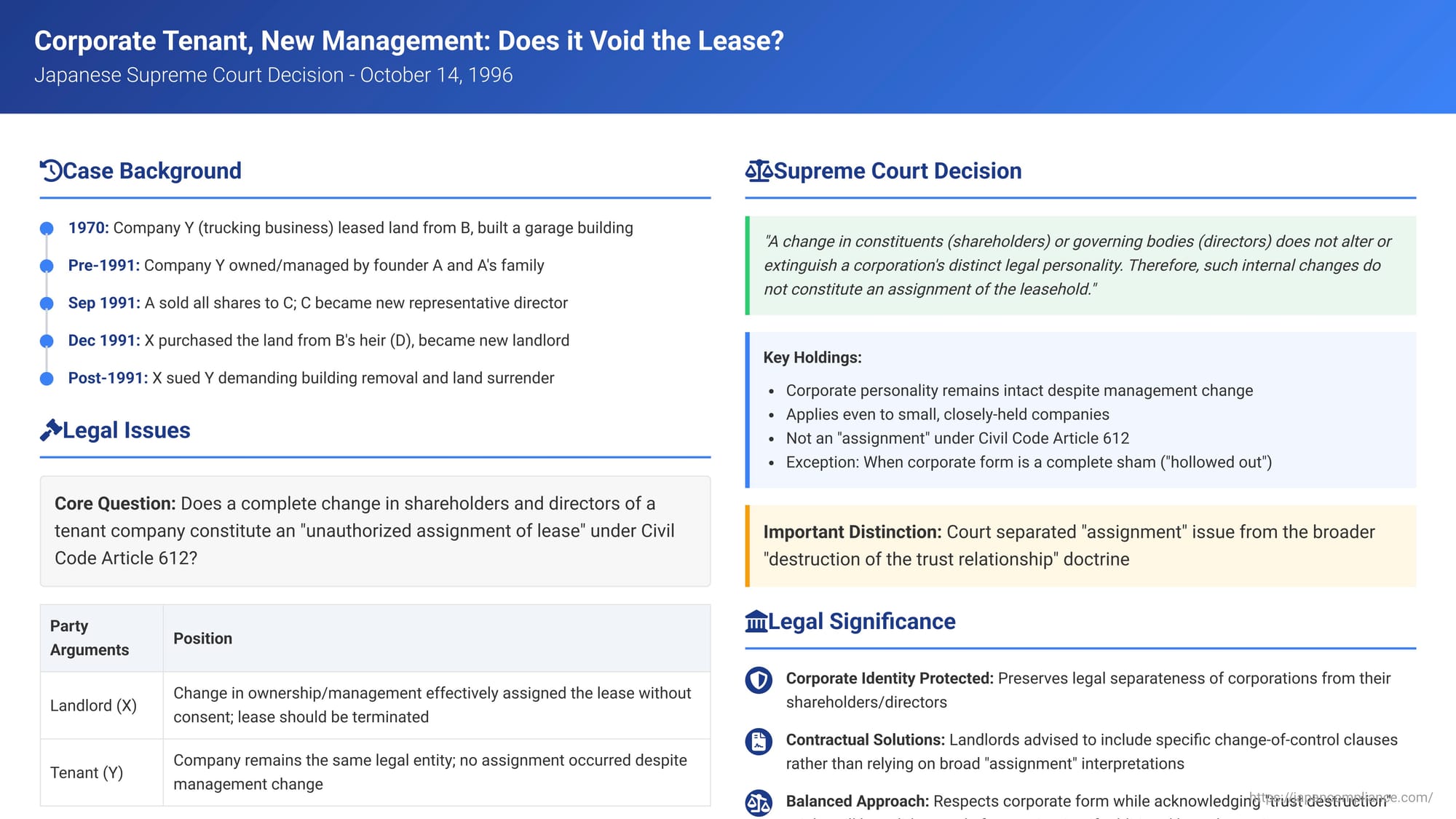

In the world of commercial real estate, the stability of lease agreements is paramount. A recurring question, particularly relevant in Japan, is what happens to a commercial lease when the tenant company undergoes a significant change in its ownership or management. Does a new captain at the helm mean the landlord can scuttle the existing lease? The Japanese Supreme Court addressed this intricate issue in a noteworthy decision on October 14, 1996, navigating the interplay between corporate personality, leasehold rights, and the foundational Japanese legal concept known as the "doctrine of destruction of the trust relationship."

The Setting: A Trucking Company's Lease and Change of Guard

The case revolved around the following factual scenario:

- The Tenant Company (Y): Y was a limited company engaged in the freight trucking business, with a stated capital of 20 million yen. From its inception, all its shares were owned by its founder and representative director, A, and A's family. The company's board of directors was also composed of A, A's family members, and other relatives.

- The Lease and Building: In 1970, Company Y entered into a lease agreement with B, the owner of a parcel of land (the "Subject Land"). The purpose of the lease was for Y to own a building on the site. Y subsequently constructed a building (the "Subject Building") on the Subject Land, which it used as a garage and operational base for its trucking business.

- Change in Ownership and Management of Y: On September 20, 1991, a significant change occurred. A and A's family sold all their shares in Company Y to C, an individual who also operated a personal trucking business. On that same day, A and all existing directors of Y resigned. C was appointed as the new representative director of Y, and C's family members filled the other directorial positions. Following this transition, C assumed control of Y's management. Company Y continued its trucking operations, integrating its pre-existing vehicles and employees with those from C's personal business, all while continuing to use the Subject Land and Subject Building.

- Change in Land Ownership: The original lessor, B, had passed away in 1985. B's child, D, inherited the Subject Land. Later, on December 4, 1991, X and others (collectively "X," the plaintiffs) purchased the Subject Land from D, becoming the new landlords.

- The Lawsuit: X, as the new owners of the Subject Land, filed a lawsuit against Company Y, demanding the removal of the Subject Building and the surrender of the Subject Land, based on their ownership rights.

- Defenses and Counter-Claims: Company Y defended its possession by asserting its valid leasehold rights to the Subject Land. In response, X, the new landlords, argued that the lease agreement had been terminated. They presented two main grounds for termination:

- An unauthorized assignment of the leasehold by Y.

- A destruction of the trust relationship between the landlord and tenant.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court found that there was no unauthorized assignment of the lease. It reasoned that although Y's representative director and shareholders had changed, Y's corporate personality remained the same, so the lease had not been "assigned" to a new entity. However, this court did find that the trust relationship between the landlord (D, at the time of the management change) and Y had been completely destroyed when A sold the management control of Y to C. On this basis, it ruled in favor of X.

- Company Y appealed. The High Court also ruled against Y but on different grounds. It held that while Y's corporate personality formally persisted, in the context of small, closely-held companies, land leases are typically founded on the personal trust between the landowner and the company's actual manager. Therefore, the High Court viewed the change in Y's management from A to C as, in substance, an assignment of the lease from A (the old manager) to C (the new manager). Since this "substantive assignment" occurred without the landlord's consent, it justified termination. Company Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Conundrum at the Supreme Court

The core issue before the Supreme Court was whether a complete change in the shareholders and active management of a lessee company—particularly a small, closely-held one—amounts to an "assignment of the leasehold" under Article 612 of the Japanese Civil Code. This article generally requires a landlord's consent for a tenant to assign a lease, and permits termination if this rule is breached.

The Supreme Court's Clarification

On October 14, 1996, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court provided the following clear reasoning:

- "Assignment of Leasehold" Defined: The Court began by examining Article 612 of the Civil Code. This article states that a lessee cannot assign the leasehold without the lessor's consent and that if the lessee violates this by allowing a third party to use or profit from the leased property, the lessor can terminate the lease. The Court emphasized that an "assignment of leasehold" inherently means a transfer from the lessee to a distinct third party.

- Corporate Personality and Internal Changes: When the lessee is a corporation, changes in its constituents (e.g., shareholders) or its governing bodies (e.g., directors) do not alter or extinguish the corporation's distinct legal personality. Therefore, such internal changes do not constitute an assignment of the leasehold from the corporation to someone else. The corporation, as the original lessee, remains the lessee.

- Application to Closely-Held Companies: This principle holds true even for small, closely-held limited companies where a particular individual effectively controls operations and the shareholders and directors are mainly that individual, their family, or close associates. A change in the de facto manager through share transfers and director resignations/appointments does not, in itself, constitute an "assignment of the leasehold" as contemplated by Article 612.

- Impropriety of Disregarding Corporate Personality: The Court stated that to interpret such a change in management as an assignment of the lease would be to improperly disregard the lessee company's distinct corporate personality. This is not justifiable unless the company's corporate form is found to be a complete sham or entirely "hollowed out" (a situation where the company has no real substance or independent activity).

- Landlord's Protective Measures: The Supreme Court pointed out that landlords are not without recourse if they place particular importance on the personal attributes, creditworthiness, or relationship with the individual(s) managing a corporate tenant. Landlords can:

- Choose to contract directly with the individual manager as the lessee, rather than with the company.

- Include specific clauses in the lease agreement with the company, stipulating, for example, that the lease can be terminated if the company changes its directors or its significant shareholding structure without the landlord's prior consent.

Given these available contractual safeguards, interpreting "assignment of lease" narrowly (as not including mere internal changes in corporate management) does not unfairly prejudice the landlord's interests.

- Application to the Facts: In Y's case, while it was a small, closely-held company whose effective management transitioned from A to C, Y clearly possessed the substance of a functioning limited company. It had assets, employees, and actively conducted its trucking business. Its corporate personality was not a mere shell. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the change in its management did not amount to an assignment of the lease. The High Court had erred in its interpretation of Article 612.

Distinguishing Lease Assignment from "Destruction of Trust Relationship"

Crucially, the Supreme Court drew a clear distinction:

- No Assignment: The change in Y's management was not an assignment of the leasehold under Article 612.

- Separate Issue of Trust: However, the Court noted that whether the fact of a change in a lessee company's management could be assessed as damaging the trust relationship between the landlord and tenant, and whether this, in conjunction with other circumstances, could become grounds for terminating the lease, is a separate legal question.

This references the well-established Japanese legal principle known as the "doctrine of destruction of the trust relationship" (信頼関係破壊の法理 - shinrai kankei hakai no hōri).

- Background of the Doctrine: Article 612 of the Civil Code allows lease termination for unauthorized assignment or subletting. This is traditionally understood to be because leases are ongoing relationships built on mutual personal trust, and such unauthorized acts are presumed to be "acts of bad faith" (背信的行為 - haishinteki kōi) that undermine this trust.

- Judicial Refinement: However, Japanese courts, in a landmark 1953 Supreme Court case (Sept. 25, 1953), established that even if there's an unauthorized assignment or sublease, the landlord cannot terminate if the tenant's act, in light of "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), does not amount to a betrayal of trust warranting termination.

- General Application: This principle evolved into a broader doctrine applicable to various grounds for lease termination: generally, a lease cannot be terminated unless the tenant's conduct (be it non-payment of rent, misuse of property, or other breaches) is severe enough to be deemed a destruction of the essential trust relationship between the parties.

- Implication of the 1996 Ruling: While the 1996 Supreme Court found no "assignment" in Y's case, its reference to the change of management potentially "damaging the trust relationship" when combined with "other circumstances" left the door open for termination on different grounds. Legal commentary suggests that these "other circumstances" would typically need to involve some breach of the tenant's obligations under the lease, whether explicit or implied by the principle of good faith. Mere change of management, absent such a breach, is unlikely to suffice on its own for termination even under the broader trust doctrine. The destruction of trust usually needs to be linked to a tenant's culpable act related to the lease.

The "Hollowed-Out Corporation" Exception

The Supreme Court did hint at a possible exception. If the lessee company had no real operational substance and its corporate personality was "entirely hollowed out" (法人格が全く形骸化している - hōjinkaku ga mattaku keigaika shiteiru), the situation might be viewed differently. In such extreme cases, where the corporate form is merely a shell being manipulated, a change in its control could potentially be treated as a de facto assignment of the lease by the individuals actually benefiting from it. However, this was not the situation with Company Y.

Why the Case Was Remanded

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the High Court because the record indicated that X (the landlords) had also alleged other grounds for termination besides the unauthorized assignment claim. The remand was for the High Court to examine these other grounds, presumably focusing on whether the change in management, coupled with any other relevant facts or alleged breaches by Y, constituted a destruction of the trust relationship sufficient to justify termination.

Implications for Commercial Leases

This 1996 Supreme Court decision provides important clarity:

- For corporate tenants, it affirms that internal restructuring, changes in shareholding, or management turnover do not automatically expose them to lease termination under the guise of an "unauthorized assignment," provided the company maintains its genuine corporate existence.

- For landlords, it underscores the importance of due diligence and contractual foresight. If the personal identity, financial strength, or specific management style of the individuals behind a corporate tenant is crucial, landlords should address this through specific lease clauses (e.g., change-of-control clauses) or by contracting with the individuals directly, rather than relying on a broad interpretation of "assignment" to later object to internal corporate changes.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1996 ruling strikes a balance. It respects the legal separateness of a corporate entity from its shareholders and managers, preventing lease terminations based solely on internal changes within a tenant company. At the same time, it acknowledges that the broader "doctrine of destruction of the trust relationship" remains a potential avenue for landlords if such changes, combined with other detrimental conduct by the tenant, genuinely undermine the foundation of the lease. This decision continues to be a key reference for navigating landlord-tenant disputes involving corporate entities in Japan.