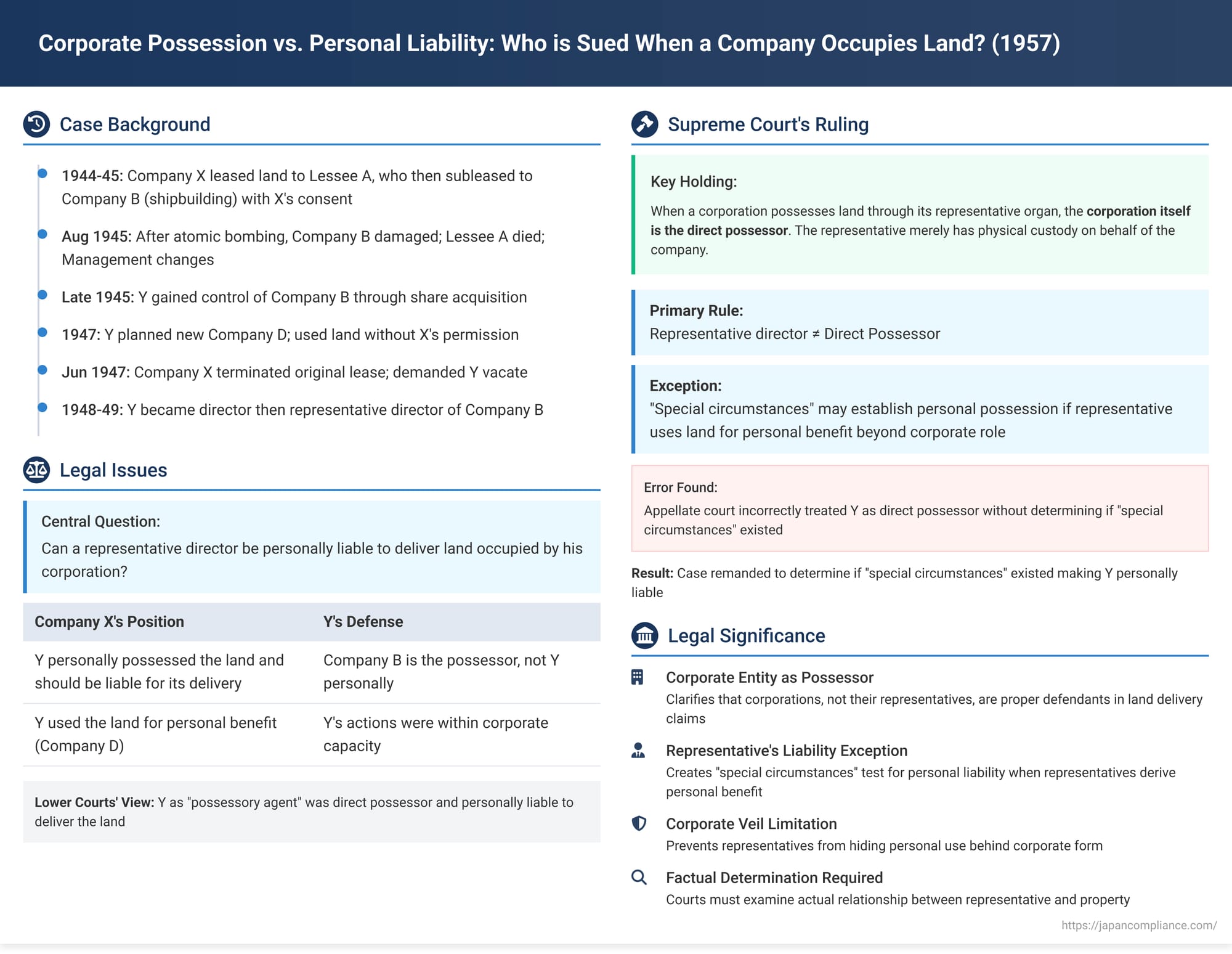

Corporate Possession vs. Personal Liability: Who is Sued When a Company Occupies Land?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of February 15, 1957 (Showa 32) (Case No. 920 (O) of 1954 (Showa 29))

Subject Matter: Claim for Land Delivery and Damages (土地引渡並びに損害金請求事件 - Tochi Hikiwatashi narabi ni Songaikin Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

This article examines a 1957 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that delves into the nuanced legal concept of possession (占有 - sen'yū) when land is occupied by a corporation. Specifically, the case addresses whether the individual who acts as a representative organ of a company, such as its representative director, can be held personally liable for the delivery of land that the company occupies. The Court's decision clarifies that, generally, the corporation itself is considered the direct possessor, while its representative organ merely has physical custody. However, it also carves out an exception where "special circumstances" might render the representative personally liable as a possessor.

The dispute involved Company X (appellee/plaintiff), the landowner, and Y (appellant/defendant), an individual who had gained effective control and later became the representative director of Company B, the entity that was physically using the land.

Factual Background

Around 1944, Company X leased the land in question (the "Land") and other properties to Original Lessee A. On February 23, 1945, Original Lessee A, upon becoming a director at the incorporation of Company B (a shipbuilding company), subleased the Land to Company B. Company B used the subleased land as a shipyard and ship repair facility. Company X consented to this sublease.

Following the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, Company B's office and factory were damaged, and Original Lessee A passed away. Director C, who was the representative director of Company B, transferred all his shares to Y (the appellant), entrusted Y with the entire management of Company B, and returned to his hometown. The remaining two directors also effectively resigned by the end of 1945, transferring their shares to Y. As a result, Y came to own the majority of Company B's shares and wielded effective control over the company.

Around early 1947, Y, along with five others, planned to establish a new company, Company D, intending to use the Land and Company B's facilities on it for building and repairing wooden ships. Around April or May 1947, construction of fishing boats began in the name of the yet-to-be-incorporated Company D, and the Land was used for this purpose without Company X's permission. Concerned about this unauthorized use, Company X, around June 7, 1947, mutually agreed with Heir E (who had succeeded to Original Lessee A's position) to terminate the original lease agreement for the Land and subsequently demanded that Y vacate the Land. Due to this dispute over land use, Company D's establishment objectives became unattainable by around November 1947. Later, Y officially became a director of Company B on January 14, 1948, and its representative director on October 20, 1949.

Company X sued Y personally, seeking delivery of the Land and damages equivalent to rent from April 1, 1947, to November 12, 1947. Y contested the claim, arguing, among other things, that Company B had the right to possess the land (arguing that a sub-lessee with the original lessor's consent does not lose their right to possess merely because the main lease is terminated by agreement) and that, in any event, the possessor of the Land was Company B, not Y personally.

The appellate court had dismissed Y's appeal from a first-instance judgment that had found Y liable. The appellate court reasoned that:

- Initially, after Y took over management of Company B based on Director C's entrustment, Y possessed the Land as an agent for Company B (代理占有 - dairi sen'yū, meaning Y was a "possessory agent directly possessing").

- When Y planned to establish Company D and used the Land in Company D's name, Y's possession became possession for himself (自己占有 - jiko sen'yū, meaning "possession for oneself, not for Company B").

- After Company D's establishment failed and Y became the representative director of Company B, Y possessed the Land as the representative organ of Company B.

The appellate court concluded that Y, as a "possessory agent" (占有代理人 - sen'yū dairinin) of Company B, was directly possessing the Land. Since it also found that Company B had no valid right to possess (rejecting the argument that the sublease survived the termination of the main lease under these circumstances of unauthorized use), Y was personally obligated to deliver the Land.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court found the appellate court's reasoning regarding Y's personal liability for possession as a representative organ to be flawed and remanded the case to the Hiroshima High Court.

The Court's key points were:

- Possession by a Corporation through its Representative Organ:

The appellate court found that Y was possessing the Land as the representative director of Company B, i.e., as its representative organ (代表機関 - daihyō kikan). If this is the case, then the actual possessor (占有者 - sen'yūsha) of the Land is Company B itself. Y, in his capacity as a representative organ, merely has physical custody or control (所持 - shoji) of the land on behalf of the company.

Therefore, in such a relationship, the direct possessor (直接占有者 - chokusetsu sen'yūsha) of the Land is Company B, and Y personally is not the direct possessor. - Exception: "Special Circumstances" for Personal Possession:

The Court acknowledged an exception: "However, if there are special circumstances indicating that Y possessed the Land not merely as an organ of Company B but also for Y's own personal benefit or purposes, then Y could also hold the status of a direct possessor, and in such a case, the claim [against Y personally] would be well-founded." - Appellate Court's Error:

The appellate court, having found that Y was possessing as Company B's representative organ, had simply labeled Y a "direct possessor as a possessory agent" and ordered Y personally to deliver the land. This was deemed an error in the legal interpretation of corporate possession. The appellate court had not made any findings regarding the "special circumstances" that might justify treating Y as a personal direct possessor in addition to or instead of Company B, particularly for the period after Y formally became representative director.

The Supreme Court concluded that this misapplication of the law concerning corporate possession constituted an insufficient deliberation and inadequate reasoning, clearly affecting the judgment. The judgment was therefore quashed and the case remanded for a new trial to determine, among other things, if such "special circumstances" existed that would make Y personally liable as a direct possessor, especially considering the different phases of Y's involvement with the land.

Analysis and Implications

This 1957 Supreme Court decision is fundamental in clarifying the distinction between a corporation's possession and the physical control exercised by its human representatives.

- Corporation as the Direct Possessor: The general rule established is that when a corporation occupies land, the corporation itself is considered the legal possessor. Its representative organs (like directors) who physically manage or control the property on behalf of the corporation are not, by virtue of their representative status alone, considered personal possessors of the property. They are merely instruments through which the corporation exercises its possession.

- Action Against the Corporation, Not Usually the Individual Representative: Consequently, if a landowner seeks to recover possession of land unlawfully occupied by a corporation, the proper defendant for a claim demanding delivery of the land is generally the corporation itself, not its individual directors or employees in their personal capacity, assuming they are acting solely as organs of the company.

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception: The crucial exception introduced by the Court is where "special circumstances" exist that show the individual representative is possessing the land not merely as an organ of the company but also for their own personal account or benefit. In such cases, the individual can also be deemed a direct possessor and thus be a proper defendant in an eviction action.

- The PDF commentary on this case suggests that an example of "special circumstances" could be where a representative director uses the company's property (e.g., a house on the land) as their personal family residence.

- The judgment's phrasing "Y is directly占有者たる地位をも有するから" (Y also possesses the status of a direct possessor) implies that, under special circumstances, the individual's personal direct possession can co-exist with the corporation's direct possession.

- Importance of Factual Determination of "Special Circumstances": The remand highlights that whether such "special circumstances" exist is a factual question that requires careful examination by the lower courts. It's not enough to simply be a director; there must be evidence of personal use or benefit distinct from, or in addition to, the corporate purpose.

- Distinction from Possessory Agents (占有代理人 - Sen'yū Dairinin): The appellate court's terminology was somewhat confused. A "possessory agent" (who possesses on behalf of another, the principal, allowing the principal to have indirect possession) is different from a "representative organ" (who is the company for the purpose of its actions, with the company itself being the direct possessor). The Supreme Court corrected this by emphasizing that if Y was acting as an organ, Company B was the direct possessor.

This judgment provides essential clarity on who to sue when seeking to recover land occupied by a corporation. While the corporation is the primary target, the "special circumstances" exception allows for claims against individuals if their personal use and control of the property can be established, preventing individuals from improperly shielding their personal occupation behind a corporate veil. The case underscores the need for precise factual findings regarding the nature and purpose of the individual's physical control over the property.