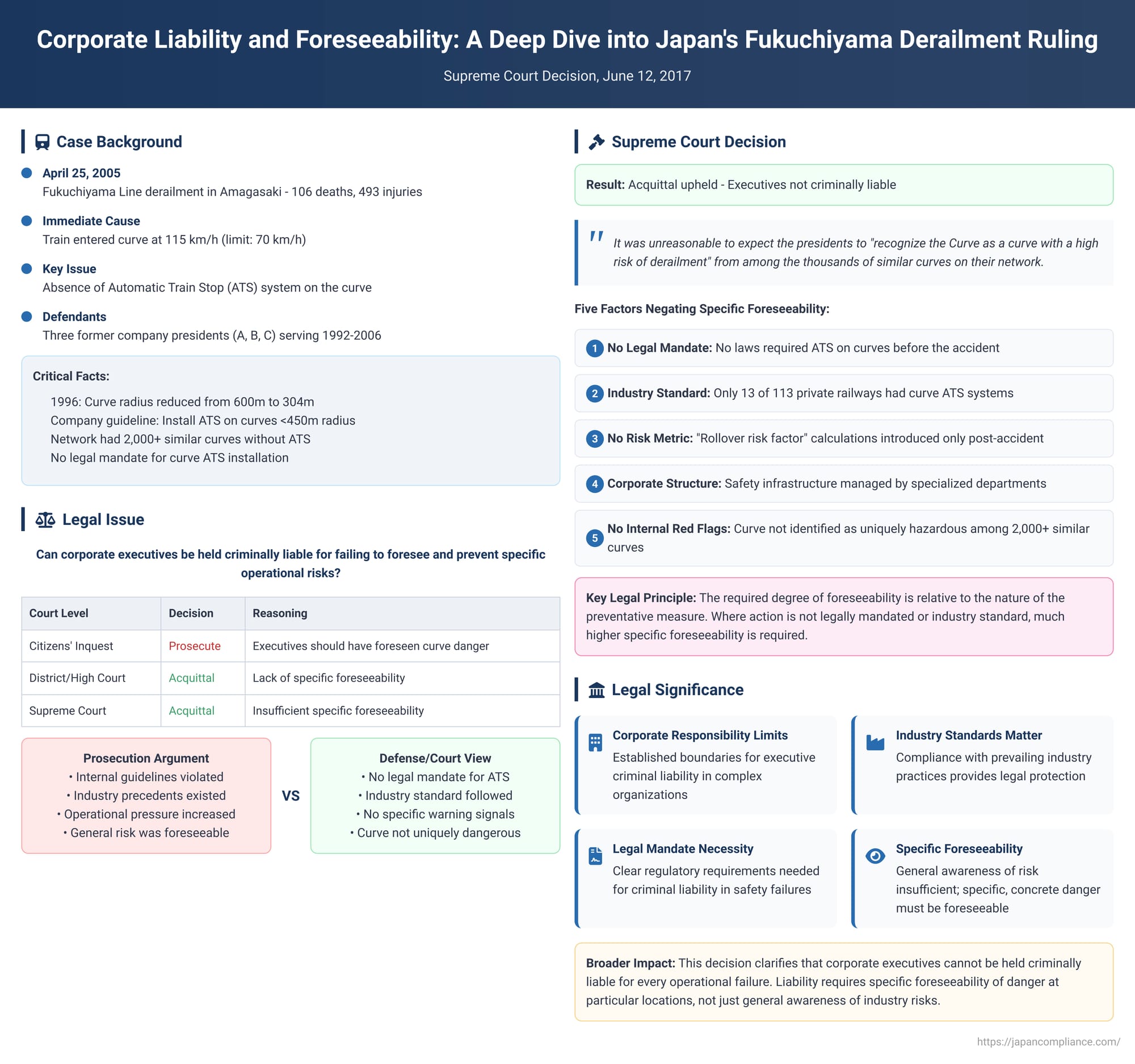

Corporate Liability and Foreseeability: A Deep Dive into Japan's Fukuchiyama Derailment Ruling

Introduction

On April 25, 2005, a horrific tragedy struck the city of Amagasaki, Japan. A seven-car rapid commuter train on the Fukuchiyama Line derailed while entering a curve, smashing into a nearby apartment building. The devastating accident resulted in the deaths of 106 people, including the young driver, and left 493 others injured. The immediate cause was clear: the train had entered the curve at approximately 115 km/h, far exceeding both the 70 km/h speed limit and the track's physical rollover limit.

This event set the stage for one of Japan's most significant legal battles over corporate criminal liability in recent history. While the driver was directly at fault, a critical question emerged: were the top executives of the major railway operator criminally responsible for the disaster? The specific point of contention was the absence of an Automatic Train Stop (ATS) system on the curve where the derailment occurred—a safety device that could have automatically slowed the train and prevented the accident.

Prosecutors initially declined to indict the company's three former presidents. However, a citizens' inquest panel, a unique feature of the Japanese legal system, twice voted to compel their prosecution for professional negligence resulting in death and injury. The ensuing legal odyssey culminated in a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 12, 2017, which ultimately acquitted the executives. This final ruling provides a nuanced and powerful examination of corporate executive responsibility, the crucial legal concept of foreseeability, and the significant role that industry standards and government regulations play in defining the scope of a corporation's duty of care.

The Incident and the Indictment

To understand the court's decision, one must first grasp the specific circumstances that led to the prosecution's argument. The case against the three former presidents—let us call them A, B, and C, who served consecutively from 1992 to 2006—was not about their direct involvement but about their alleged failure to proactively manage a known risk.

The Curve: The section of track in question, referred to as "the Curve," had undergone significant changes. In 1996, construction work related to a new rail link (the Tozai Line) altered the track's geometry. The Curve's radius was sharply reduced from a gentle 600 meters to a much tighter 304 meters. This engineering change necessitated a reduction in the speed limit on the Curve from 95 km/h to 70 km/h. Complicating matters, the long, straight section of track immediately preceding the Curve had a speed limit of 120 km/h. This created a scenario where trains would approach a sharp, speed-restricted bend at very high speeds, requiring significant and timely braking by the driver.

The Missing Safeguard: The Automatic Train Stop (ATS) system is a critical safety feature designed to prevent accidents caused by human error. Early versions were developed to halt trains that ran through red signals. However, more advanced versions incorporate a speed-checking function that can monitor a train's velocity and automatically apply the brakes if it exceeds a preset limit at a specific location, such as a sharp curve. The Curve at Amagasaki was not equipped with this type of advanced ATS.

The Prosecution's Argument: The designated attorneys acting as prosecutors built their case on the principle of foreseeability. They argued that the three former presidents, as the ultimate authorities on operational safety, could and should have foreseen the specific danger posed by the Curve and, therefore, had a professional duty to order the installation of a speed-checking ATS. Their argument rested on several key points:

- The Engineering Changes: The presidents were aware, or should have been aware, of the 1996 construction that made the Curve significantly sharper and more dangerous.

- Internal Standards: The railway company itself had an internal guideline to install ATS on curves with a radius of less than 450 meters. The Curve, at 304 meters, fell well within this self-imposed danger category.

- Increased Operational Pressure: A 1997 timetable revision substantially increased the number of rapid trains on the Fukuchiyama Line. Prosecutors argued this heightened the pressure on drivers to maintain tight schedules, making it more likely they would enter the Curve at excessive speeds.

- Industry Precedents: There had been prior derailment accidents on curves at other railway companies in Japan caused by excessive speed, establishing that such events were a known type of operational risk.

Based on these factors, the prosecution contended that the risk of a high-speed derailment on the Curve was not a remote possibility but a concrete, foreseeable danger. They argued that this foreseeability created a clear duty of care for the presidents, which they negligently breached by failing to instruct the head of the Railway Headquarters to prioritize and install an ATS on the Curve.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Lack of Specific Foreseeability

In its final judgment, the Supreme Court upheld the acquittals from the lower courts. The core of its reasoning was that while the accident was a foreseeable tragedy in a general sense, the presidents could not be expected to have possessed the specific foreseeability required to single out the Curve as a point of exceptional danger demanding their direct intervention.

The court systematically dismantled the prosecution's argument by focusing on the operational and regulatory realities at the time of the accident. It articulated five crucial factors that negated the claim of specific foreseeability for the top executives:

- Absence of a Legal or Regulatory Mandate: Critically, before the accident, there were no laws or government regulations in Japan that required railway operators to install ATS systems with speed-checking capabilities on curves. While ATS for signal-passing prevention was standard, its application to curves was a voluntary, not a mandatory, safety enhancement.

- Prevailing Industry Practice: The court found that the railway company's practice was in line with the industry norm. At the time, the overwhelming majority of railway operators in Japan had not installed ATS on curves. Out of 113 private railway companies, only 13 had done so, and among the national Japan Railways (JR) Group companies, only three, including the one in question, had started the process. The failure to equip the Curve was not an outlier but was consistent with the prevailing standard of care across the entire Japanese railway industry.

- No Standardized Risk-Assessment Metric: The concept of using a "rollover risk factor"—a scientific calculation to determine a curve's danger level—was only introduced into transport ministry regulations after the Fukuchiyama derailment. Before the accident, neither the defendant company nor any other operator used this method to identify and prioritize which curves needed ATS installation. Without a uniform, objective metric, it was difficult to argue that one specific curve should have been seen as exceptionally dangerous.

- Corporate Structure and Information Flow: The court recognized the realities of a large corporate structure. The responsibility for planning and implementing safety infrastructure like ATS was delegated to a specialized department, the Railway Headquarters. The presidents, as top executives, were responsible for broad safety policy and strategy. They were not, however, routinely briefed on the specific engineering characteristics or potential risks of every individual curve on the network. There was no established channel for information about the danger of one particular curve to reach the president's desk.

- No Internal Red Flags: Perhaps most persuasively, the court noted that there was no evidence that the Curve was ever recognized internally as being uniquely hazardous. The company's network contained over 2,000 curves with a radius of 300 meters or less. Nothing had occurred prior to the accident to elevate the Curve in question above any of these others in the eyes of the company’s safety and engineering experts. It had simply not been identified as a priority.

In light of these facts, the court concluded that it was unreasonable to expect the presidents to "recognize the Curve as a curve with a high risk of derailment" from among the thousands of similar curves on their network.

Foreseeability, Duty of Care, and "Accepted Risk"

The Supreme Court's decision delves deep into the relationship between foreseeability and the duty of care, a central pillar of negligence law. The prosecution had attempted to draw an analogy to precedents from large-scale fire cases in Japan. In those cases (e.g., hotel fires), courts had found that the mere fact that a fire, if one were to start, could easily lead to deaths was sufficient to establish foreseeability and a strict duty on owners to have robust fire prevention systems in place. The argument was that, similarly, the knowledge that a driver could speed on the Curve and cause a derailment should be enough to establish the presidents' duty to install an ATS.

The Supreme Court explicitly rejected this analogy. It drew a sharp distinction between the two scenarios. In the fire cases, there were often extensive and specific laws and regulations already in place that mandated fire safety equipment and procedures. The negligence in those cases stemmed from violating a clear, pre-existing duty. In the Fukuchiyama case, as the court repeatedly emphasized, no such legal or regulatory duty to install ATS on curves existed.

This distinction highlights a sophisticated legal principle: the required degree of foreseeability is not absolute but is relative to the nature of the preventative measure being considered.

- Where a preventative action is clearly defined, legally mandated, or a well-established industry standard, even a low probability of an accident may be enough to trigger a duty of care. The path to avoiding the result is clear.

- However, where a preventative action is not legally required, is not standard industry practice, and would impose a significant burden if applied universally (such as retrofitting thousands of curves with expensive ATS technology), the law requires a much higher, more specific, and more concrete level of foreseeability of danger at a particular location before it will impose a duty to act.

The court effectively ruled that, based on the technological and safety standards of the time, operating the line without an ATS on the Curve fell within the bounds of "accepted risk." To convict the presidents would be to retroactively apply the safety standards of the post-accident era and hold them criminally liable for failing to be ahead of their time. It would impose an immense burden, suggesting they had a duty to simultaneously upgrade all 2,000+ similar curves—a task deemed beyond what could be reasonably and legally required of them at the time.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's acquittal of the three former executives in the Fukuchiyama derailment case is a sobering yet legally sound decision. It does not absolve the railway company of its moral responsibility for the tragedy, but it carefully defines the stringent requirements for establishing individual criminal guilt for professional negligence at the executive level.

The judgment powerfully illustrates that corporate liability is not an abstract concept. It is anchored in the concrete realities of the operating environment. The court's decision was not a single-factor analysis but a holistic assessment of the legal landscape, prevailing industry-wide safety practices, the established scientific and technical standards of the day, and the internal realities of corporate governance and information flow. It affirmed the principle that foreseeability in the context of corporate negligence must be specific and concrete, not merely general or abstract. For a duty of care to arise for a top executive regarding a specific operational risk, that risk must be something that they could, and should, have reasonably been able to identify and act upon based on the information and standards available at the time.