Corporate Cash and Political Clout: The Yahata Steel Case and the Legality of Company Donations in Japan

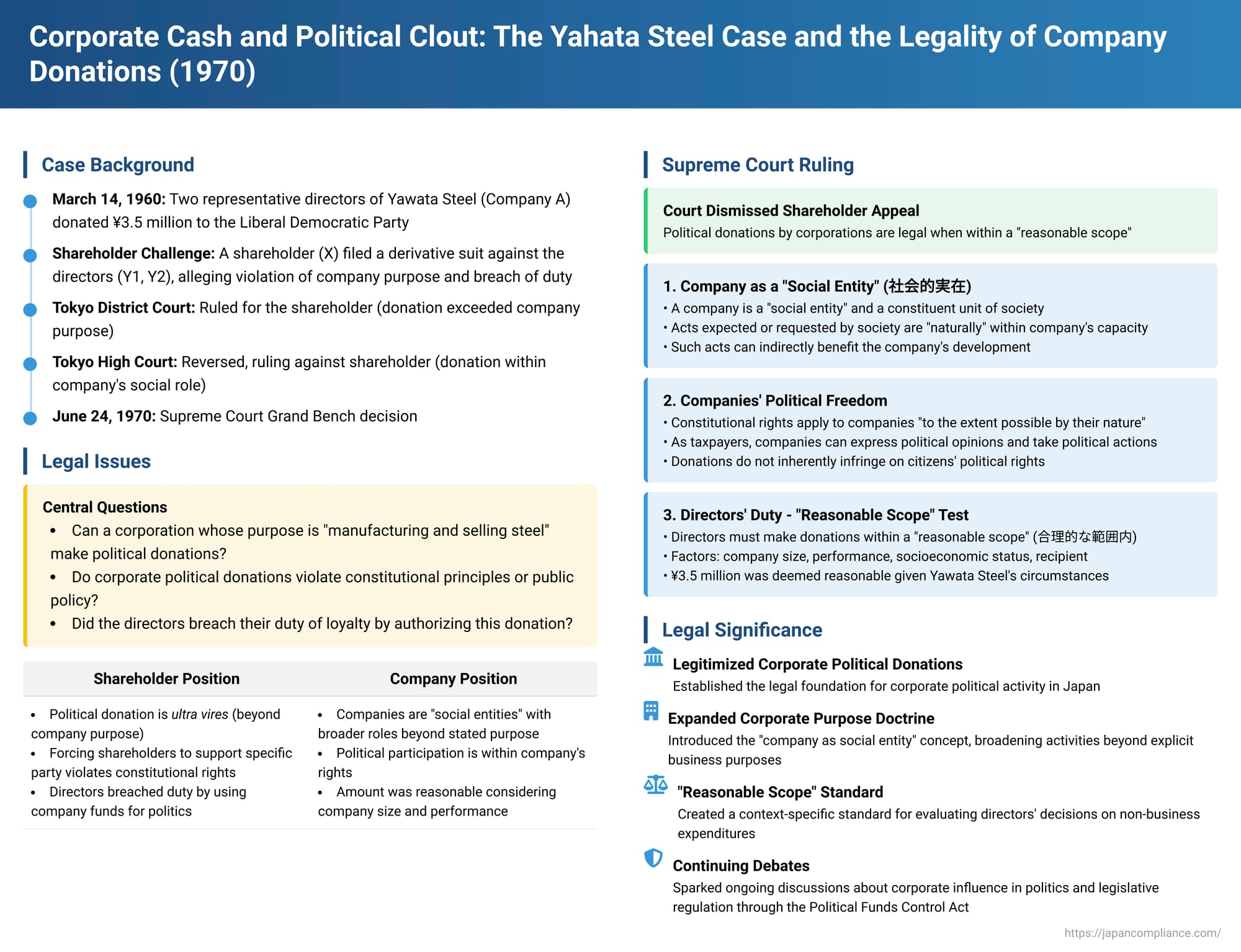

The role of corporations in the political sphere, particularly through financial contributions to political parties, is a contentious issue in many democracies. In Japan, a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court on June 24, 1970, famously known as the Yahata Steel Political Donation Case, addressed the fundamental questions of whether companies possess the legal capacity to make such donations, whether these contributions violate public policy, and the scope of directors' duties when authorizing them. This case has profoundly shaped the legal landscape surrounding corporate political involvement in Japan.

The Donation and the Shareholder Challenge

The case centered on Company A (a major steel manufacturer, Yahata Steel & Iron Co., Ltd.), whose articles of incorporation stated its business purpose as "the manufacture and sale of steel and businesses incidental thereto". On March 14, 1960, two of Company A's representative directors, Y1 and Y2 (the defendants/appellees), acting on behalf of the company, donated 3.5 million yen to the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

A shareholder of Company A, Mr. X (the plaintiff/appellant), initiated a derivative lawsuit against directors Y1 and Y2. Mr. X argued that this political donation was an act outside the scope of Company A's purpose as defined in its articles of incorporation (ultra vires). He further contended that the donation constituted a breach of the directors' duty of loyalty to the company, and sought damages on behalf of Company A for the amount donated.

Lower Court Decisions: Conflicting Views

The journey of the case through the lower courts revealed sharply contrasting judicial philosophies on the matter:

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court ruled in favor of the shareholder, Mr. X. It categorized corporate actions into "transactional acts" and "non-transactional acts." Political donations, it found, belonged to the latter category. The court reasoned that such donations were contrary to a company's inherent profit-making objective and therefore fell outside its stated purpose. Furthermore, it held that the donation could not be justified as a permissible "social obligation" of the company.

- Tokyo High Court (Second Instance): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision, ruling against Mr. X. It placed significant emphasis on the crucial role political parties play in a representative democracy. The High Court opined that since a company is recognized as a social entity ("social person"), any act that is beneficial to society, when viewed from the company's relationship with society, naturally falls within the scope of its corporate purpose.

Dissatisfied with the High Court's ruling, Mr. X appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Pronouncements

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its seminal decision, affirmed the High Court's judgment, thereby dismissing Mr. X's appeal. The Court's reasoning addressed three core legal issues: the company's capacity to make political donations, the conformity of such donations with public policy, and the directors' duties.

I. Political Donations and Corporate Purpose (Legal Capacity/Rights)

The Supreme Court extensively discussed whether a political donation falls within a company's legal capacity, which is traditionally understood to be limited by its stated purpose in the articles of incorporation.

- The Company as a "Social Entity": The Court declared that a company, much like a natural person, is a "social entity" (社会的実在 - shakaiteki jitsuzai) and a constituent unit of the state, local public entities, and the broader community. As such, it "inevitably bears social functions" or responsibilities.

- Socially Expected Acts: Based on this premise, the Court reasoned that even if a particular corporate act appears, at first glance, to be unrelated to the company's explicitly stated business purpose, it can still be within the company's capacity. If an act is something that is "socially expected or requested" (社会通念上、期待ないし要請される - shakai tsūnenjō, kitai naishi yōsei sareru) of the company, then responding to such expectations is something the company can "naturally do".

- Indirect Benefit to the Company: The Court further elaborated that engaging in such social activities is generally not "useless or without benefit" to the company. Instead, these actions can hold "considerable value and effect in promoting the smooth development of the enterprise". In this sense, such acts, though perhaps indirectly, can be considered "necessary for the achievement of the company’s purpose". Examples given by the Court included donations for disaster relief, contributions to the local community, and financial support for welfare projects.

- Application to Political Donations: The Supreme Court explicitly extended this reasoning to political donations made by companies to political parties. It argued that since parliamentary democracy, as established by the Constitution, cannot function effectively without political parties, parties are indispensable elements of the system. Cooperating in the sound development of political parties is, therefore, an act expected of companies as social entities, and political contributions are one form of such cooperation.

The PDF commentary highlights that this characterization of political donations as "socially expected or requested" and thus "naturally permissible" drew criticism, with one prominent scholar, Professor Suzuki Takeo, calling it an "outrageous overreach" for seemingly encouraging such donations. While the Court also mentioned the indirect benefit to the company's development, some commentators argue that the primary justification for allowing donations should lie in their utility to the company's business objectives, making the "indirect benefit" aspect the decisive factor rather than a supplementary one. In contemporary times, with an increased emphasis on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), the idea of companies undertaking socially expected actions has gained more traction. However, the direct link between political donations and a company’s profit-making purpose remains a point of debate, especially as the policy differences between major political parties on fundamental economic systems may have narrowed.

II. Political Freedom of Companies and Public Policy

The appellant had argued that corporate political donations were unconstitutional and therefore violated public order and morals (as per Article 90 of the Civil Code). The Supreme Court rejected this argument.

- Company's Right to Political Action: The Court asserted that since companies, like natural persons, bear the obligation to pay taxes and contribute to the national burden, there is no reason to prohibit them from expressing opinions or taking other actions regarding the policies of national or local governments from their standpoint as taxpayers.

- It went further to state that constitutional rights and duties stipulated in Chapter III of the Constitution apply to domestic corporations to the extent possible by their nature. Therefore, companies, similar to natural citizens, possess the freedom to engage in political acts, such as supporting, promoting, or opposing specific policies of the government or political parties. Political donations were framed as an exercise of this freedom.

- No Direct Infringement on Citizens' Political Rights: The Court found that donations to political parties do not, by their inherent nature, directly affect the exercise of individual citizens' voting rights or other rights of political participation. Potential misuses of party funds, such as for vote-buying, were characterized as "pathological phenomena" that are addressed by existing regulations, not as a direct consequence of the act of donation itself.

- Conclusion on Public Policy: Since corporate political donations were deemed not to contravene the Constitution, the argument that they violated public order and morals (Civil Code Article 90) on the grounds of unconstitutionality was dismissed for lacking its premise.

The PDF commentary notes the ongoing discussion surrounding this aspect. While the Constitution guarantees political rights primarily to individual citizens, and the presence of diverse political views among shareholders is undeniable, the Court did not see corporate donations as inherently coercive to shareholders who might disagree, implying they can express dissent or divest. This contrasts with some academic views that argue such donations can force shareholders to indirectly support political causes they oppose, thus raising public policy concerns. A key point of debate is whether large corporate donations, due to their potential financial clout, can disproportionately influence political processes, thereby undermining the principle of equal political participation by individual citizens. The Political Funds Control Act, which sets limits on corporate donations based on company size, is seen by some as a legislative attempt to keep such influence within acceptable bounds.

III. Directors' Duties in Making Donations (Duty of Loyalty)

The final issue was whether the directors, by authorizing the donation, breached their duty of loyalty to the company.

- Nature of Duty of Loyalty: The Court clarified that the directors' duty of loyalty (then under Article 254-2 of the Commercial Code, now Article 355 of the Companies Act) is essentially an elaboration and reinforcement of the general duty of care of a good manager (zenkan chūi gimu) that directors owe to the company, as derived from the principles of mandate in the Civil Code (Article 644). It is not a distinctly separate or inherently "higher" duty.

- Standard of "Reasonable Scope": The Court held that when directors make political donations on behalf of the company, they are obliged to determine the amount and other specifics within a "reasonable scope" (合理的な範囲内 - gōriteki na han'i nai). This reasonableness is to be judged by considering various factors, including "the company's scale, business performance, other socio-economic status, the recipient of the donation, and other circumstances".

- No Breach in this Case: Applying this standard to the facts, the Supreme Court, taking into account Company A's capital, net profit, and dividend payments at the time, concluded that the donation of 3.5 million yen did not exceed this "reasonable scope". Therefore, the directors had not breached their duty of loyalty. The Court dismissed arguments that the directors acted improperly by not earmarking the funds or by not having the donation approved by a board resolution, noting a lack of specific pleading or proof of concrete misconduct by the directors in this regard.

The PDF commentary mentions that there is an academic debate on whether the business judgment rule should apply to decisions regarding political donations. Some lower court rulings appear to lean towards its application. However, the prevailing scholarly view tends to reject the direct application of the business judgment rule to political donations because their benefit to the company is often abstract and indirect, unlike typical business decisions. Instead, a stricter test focusing on whether the donation falls within a "reasonable scope" is advocated.

Key Takeaways and Enduring Significance

The Yahata Steel Political Donation Case was a landmark decision with several lasting implications:

- Legitimization of Corporate Political Donations: The ruling provided a legal foundation for companies in Japan to make political donations, provided they are within the company's broadly interpreted purpose and the amount is reasonable in light of the company's circumstances.

- The "Company as a Social Entity" Concept: It introduced and emphasized the idea of the company as a "social entity" with societal roles and expectations extending beyond pure profit-making. This concept has influenced subsequent discussions on corporate social responsibility.

- Balancing Interests: The decision reflects a judicial attempt to balance various interests: the company's freedom of political expression, the protection of its business interests through engagement with the political environment, concerns about shareholder rights, and broader public policy considerations regarding the influence of money in politics.

- Continued Relevance of Regulation: While the Supreme Court affirmed the legality of corporate donations in principle, the case also implicitly underscores the importance of legislative frameworks like the Political Funds Control Act, which regulates the amounts and transparency of such contributions.

Conclusion

The Yahata Steel Political Donation decision of June 24, 1970, remains a pivotal judgment in Japanese corporate and constitutional law. It navigated the complex terrain of corporate rights, directors' responsibilities, and the role of business entities in a democratic society. By affirming a company's capacity to make political contributions as a "social entity" acting within a "reasonable scope," the Supreme Court acknowledged the realities of corporate engagement in the broader socio-political environment, while also setting parameters through the directors' duty of loyalty. The decision continues to fuel debate and shape the understanding of the appropriate boundaries of corporate political involvement in Japan.