Coordinating Benefits: Japan's Supreme Court on Health Insurer Subrogation vs. Auto Liability Payments (September 10, 1998)

TL;DR

The 1998 ruling by Japan’s Supreme Court held that payments made under Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI) extinguish the victim’s entire damages claim on a yen‑for‑yen basis, thereby limiting any subrogation rights of National Health Insurance (NHI) providers to amounts still outstanding at the exact time each health‑care benefit is delivered.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: An Accident, Insurance Payments, and a Subrogation Claim

- The Legal Dispute: NHI Subrogation vs. Prior CALI Payments

- Lower Court Decisions Favoring the NHI Insurer

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (September 10, 1998)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

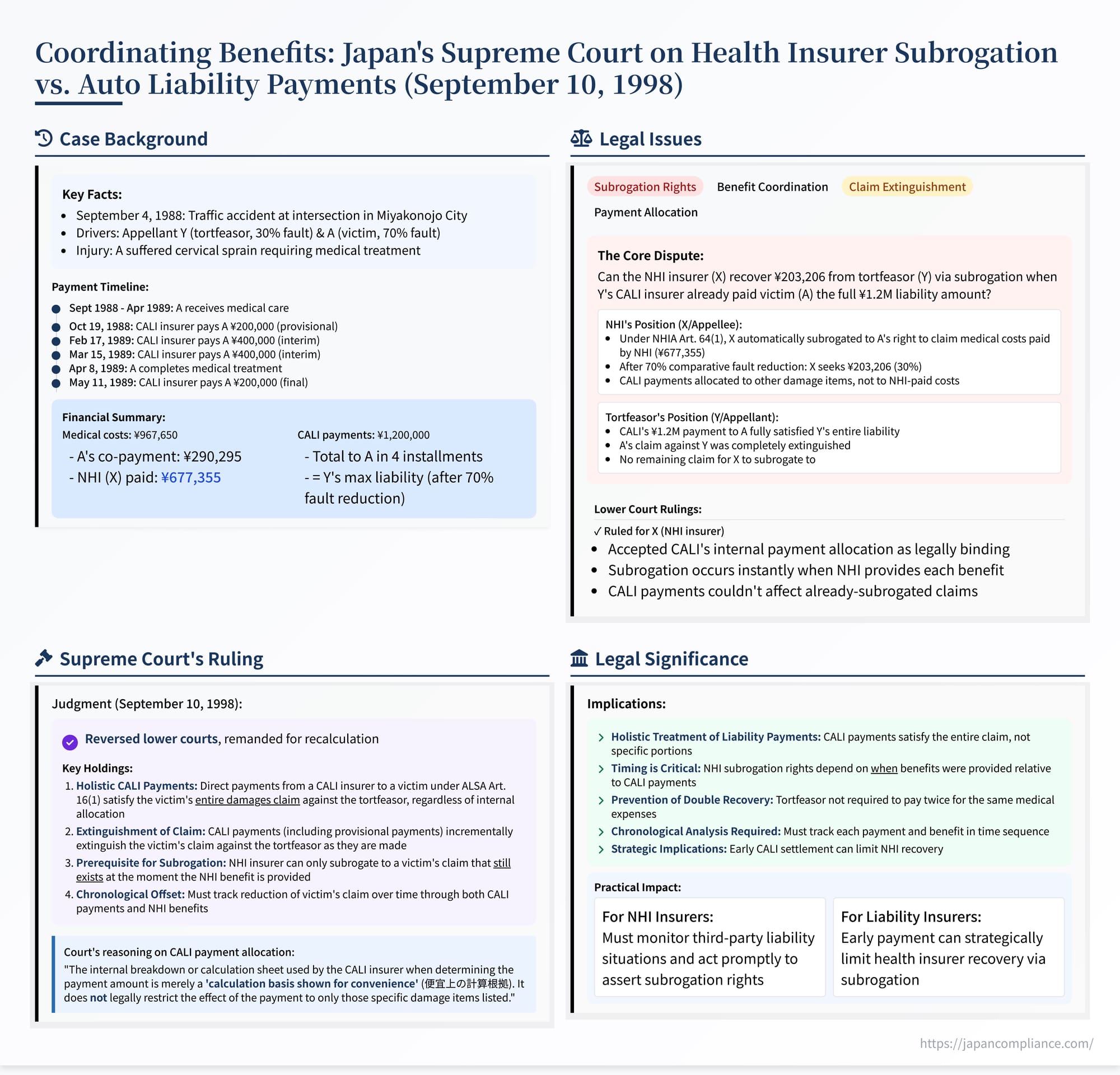

On September 10, 1998, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant judgment in a reimbursement claim case (1994 (O) No. 651). This decision addressed a critical intersection between Japan's National Health Insurance (NHI) system and its Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI, commonly known as jibaiseki hoken) system. Specifically, it clarified how payments made directly by a tortfeasor's CALI insurer to an injured victim impact the subrogation rights of the victim's NHI provider, who has covered the medical treatment costs. The Court established that CALI payments extinguish the victim's overall damages claim against the tortfeasor, regardless of internal allocations, potentially preempting the NHI insurer's ability to recover its costs via subrogation if the CALI payments are made before the NHI benefits are provided. This ruling has important implications for the coordination of benefits following traffic accidents and other third-party liability incidents involving insured individuals.

Factual Background: An Accident, Insurance Payments, and a Subrogation Claim

The case arose from a traffic accident with the following key facts established by the lower court:

- The Accident and Injury: On September 4, 1988, in Miyakonojo City, the appellant, Y, driving their passenger car, collided with a passenger car driven by A at an intersection. A suffered injuries, including cervical sprain, requiring medical treatment.

- Medical Treatment and NHI Benefits: A received inpatient and outpatient treatment from the date of the accident until April 8, 1989. A was insured under the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, administered by the appellee, X (likely the municipality or NHI association acting as the insurer). The treatment was provided as "Medical Care Benefits" (療養の給付 - ryōyō no kyūfu) under the National Health Insurance Act (NHIA). The total cost of this medical care amounted to 967,650 yen. Of this amount, A's statutory co-payment portion was 290,295 yen, while the insurer X paid the remaining 677,355 yen directly to the medical providers.

- CALI Insurance Payments to Victim: A, the injured party, made a direct claim against the insurance company providing Y's Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI or jibaiseki). Under the Automobile Liability Security Act (ALSA or Jibaihō), specifically Articles 16(1) (victim's direct claim right) and 17(1) (provisional payments), A received several payments directly from the CALI insurer:

- October 19, 1988: 200,000 yen (provisional payment - 仮渡金 kariwatashikin)

- February 17, 1989: 400,000 yen (interim payment against damages)

- March 15, 1989: 400,000 yen (further interim payment)

- May 11, 1989: 200,000 yen (final payment)

- Total CALI Payment: 1,200,000 yen (which corresponds to the statutory liability limit under CALI for injuries at that time).

- CALI Insurer's Internal Allocation: When making these payments, the CALI insurer internally calculated A's damages. Its breakdown allocated the payments primarily towards A's co-payment portion of medical expenses, lost wages, and pain and suffering (consolation money - 慰謝料 isharyō). Notably, this internal calculation did not explicitly allocate funds to cover the 677,355 yen portion of medical expenses paid by the NHI insurer, X.

- Comparative Negligence and Total Damages: The accident was found to be caused by the negligence of both parties failing to confirm safety at the intersection. Due to a stop sign facing A, A was assigned 70% fault, and Y (appellant tortfeasor) was assigned 30% fault. A's total damages from the accident were determined not to exceed 4 million yen. Consequently, after applying the comparative fault reduction (A recovering only 30% of total damages), Y's maximum legal liability to A did not exceed 1.2 million yen.

The Legal Dispute: NHI Subrogation vs. Prior CALI Payments

The NHI insurer, X, having paid 677,355 yen for A's medical treatment, initiated a lawsuit against the tortfeasor, Y. X's claim was based on the principle of statutory subrogation outlined in NHIA Article 64, Paragraph 1. This provision generally allows the NHI insurer, after providing medical benefits to an insured victim injured by a third party, to acquire (subrogate to) the victim's damages claim against that third party, up to the value of the benefits provided.

X argued that it had acquired A's right to claim damages from Y to the extent of the 677,355 yen it paid. Acknowledging A's 70% comparative negligence, X reduced its claim accordingly and sought reimbursement from Y for the remaining 30%, amounting to 203,206 yen.

Y defended against X's claim, arguing that the 1.2 million yen paid by Y's CALI insurer directly to A had completely satisfied Y's entire legal obligation to A (as A's recoverable damages, after comparative fault, did not exceed 1.2 million yen). Since A's claim against Y was fully extinguished by the CALI payments, Y contended, there was no remaining claim for the NHI insurer X to subrogate to under NHIA Article 64(1). Alternatively, Y argued that even if X initially acquired some subrogation right, it was subsequently extinguished by the full payment from the CALI insurer.

Lower Court Decisions Favoring the NHI Insurer

Both the court of first instance and the High Court (Fukuoka High Court, Miyazaki Branch) ruled in favor of the NHI insurer, X. Their reasoning was based on three main points:

- Payment Allocation: They accepted the CALI insurer's internal breakdown of the 1.2 million yen payment. Since this breakdown showed the payment covering A's co-payment, lost wages, and pain/suffering, but not the portion of medical expenses paid by X, the courts concluded that A's claim against Y specifically for the insurer-paid medical costs had not been satisfied by the CALI payment and thus remained available for X to subrogate to.

- Timing of Subrogation: They held that under NHIA Art. 64(1), the insurer's subrogation right arises automatically and transfers from the insured to the insurer incrementally each time a medical benefit (ryōyō no kyūfu) is provided. Since the CALI payments were made sequentially during and after the period X was providing benefits, these payments could not affect the portion of the damages claim that X had already acquired through subrogation at earlier points in time.

- Nature of Provisional Payments: They deemed the initial 200,000 yen provisional payment (kariwatashikin) under ALSA Art. 17(1) as not being, by its nature, a payment of damages, and therefore, it did not extinguish any part of A's underlying damages claim.

Based on this reasoning, the lower courts ordered Y to pay the amount sought by X. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (September 10, 1998)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated September 10, 1998, disagreed with the lower courts on all key points and overturned their decisions, remanding the case for recalculation.

1. Prerequisite for Subrogation: Existence of Victim's Claim:

The Court reaffirmed the fundamental principle of subrogation under NHIA Article 64(1): the NHI insurer (X) steps into the shoes of the insured victim (A) and acquires their damages claim against the third-party tortfeasor (Y) only if, and to the extent that, such a claim exists at the precise moment the NHI provides the medical care benefit. If the victim (A) receives compensation from the tortfeasor (or their insurer, like the CALI insurer) before receiving a specific NHI benefit related to the same injury, A's claim against the tortfeasor is extinguished (pro tanto) by the amount of that compensation. The NHI insurer can only subrogate to whatever portion of the claim remains at the time it provides its benefit.

2. Holistic Nature of CALI Damages Payments:

The Supreme Court crucially rejected the lower courts' reliance on the CALI insurer's internal allocation of the 1.2 million yen payment. It held that:

- Payments made by a CALI insurer directly to a victim under ALSA Article 16(1) are payments for damages arising from the bodily injury caused by the accident.

- These payments are intended to cover the victim's entire damages claim against the tortfeasor (up to the CALI policy limit), encompassing all relevant heads of damage, including medical expenses (both the victim's co-payment and the portion covered by health insurance), lost earnings, pain and suffering, etc.

- The internal breakdown or calculation sheet used by the CALI insurer when determining the payment amount is merely a "calculation basis shown for convenience" (便宜上の計算根拠 - bengijō no keisan konkyo). It does not legally restrict the effect of the payment to only those specific damage items listed.

- Therefore, the payment made by the CALI insurer extinguishes the victim's overall damages claim against the tortfeasor by the amount paid, regardless of the internal breakdown.

This holistic view means the 1.2 million yen CALI payment was applied against A's entire recoverable claim from Y (capped at 1.2 million yen due to comparative fault), including the portion related to medical expenses that X sought to recover.

3. Provisional Payments (Kariwatashikin) Also Extinguish the Claim:

The Court explicitly contradicted the lower courts regarding provisional payments. It stated that provisional payments made under ALSA Article 17(1) are clearly, by statutory interpretation, advance payments against the total damages ultimately payable under ALSA Article 16(1). Consequently, these advance payments also extinguish the victim's overall damages claim against the tortfeasor pro tanto as they are made. The initial 200,000 yen payment thus reduced A's claim against Y immediately upon payment.

4. Correct Calculation Method: Chronological Offset Required:

Based on these principles, the Supreme Court outlined the correct methodology for determining the amount, if any, recoverable by the NHI insurer (X) through subrogation:

- Determine Total Recoverable Damages: First, establish the total amount of damages A could legally recover from Y after accounting for comparative negligence (in this case, capped at 1.2 million yen).

- Chronological Tracking: Track the reduction of this total recoverable amount over time. As each payment is made by the CALI insurer (including provisional payments) or as each NHI benefit is provided by X (valued at X's cost, adjusted for A's comparative negligence), the remaining balance of A's claim against Y decreases.

- Subrogation Condition: X acquires a subrogation right only at the moment it provides a specific benefit, and only if A's claim against Y still has a positive balance at that exact moment. The amount X acquires at each instance is limited to the value of the benefit provided (adjusted for fault) or the remaining balance of A's claim, whichever is smaller.

The lower courts erred because they failed to perform this chronological analysis. They incorrectly assumed the CALI payments didn't affect the insurer-paid medical cost portion of the claim and wrongly treated the timing and nature of the payments. The Supreme Court noted that since 1 million yen was paid by the CALI insurer by March 15, 1989, while X was providing benefits until April 8, 1989, it was clear that not all CALI payments occurred after all NHI benefits were provided.

5. Remand for Recalculation:

Because the precise timing of each NHI benefit provided by X relative to the CALI payments was not clearly established by the lower courts, the Supreme Court could not definitively calculate the final subrogated amount. Therefore, the case was remanded to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings to establish the necessary facts and apply the chronological offset method correctly. The Supreme Court did note, however, that even assuming A's total claim was the maximum 1.2 million yen, given that 1 million yen was paid by CALI before the end of treatment, and X's total adjusted claim was approx. 203k yen, X could clearly subrogate to at least the first 200k yen of its claim (as this amount plus the 1M CALI payment equals the 1.2M cap). Whether X could recover the final 3k yen would depend on whether the specific NHI benefits corresponding to that amount were provided before the later CALI payments (specifically the payment on March 15, 1989) extinguished the remaining balance of A's claim.

Implications and Significance

This Supreme Court decision provides crucial guidance on the interplay between social health insurance subrogation and payments from third-party liability insurance, particularly compulsory auto insurance:

- Holistic View of Liability Payments: It establishes that payments from liability insurers like CALI providers are treated holistically as satisfying the victim's overall damages claim against the tortfeasor, irrespective of any internal allocation by the insurer. This prevents artificial segmentation of damages for subrogation purposes.

- Prior Payment Extinguishes Claim: It confirms that payments made by the tortfeasor or their liability insurer directly to the victim before the health insurer provides benefits for the same injury reduce or extinguish the victim's claim, thereby limiting or preventing the health insurer's subrogation right under NHIA Art. 64(1).

- Coordination of Benefits: The ruling underscores the importance of coordinating benefits. It prevents a potential "double recovery" scenario where the victim receives full compensation from the liability insurer, and the health insurer also recovers its costs from the same tortfeasor via subrogation, effectively making the tortfeasor pay twice for the same insured medical expenses when the initial payment already covered the full extent of their liability.

- Importance of Timing: The chronological offset method highlights the critical importance of timing. Early settlement and payment by the liability insurer can significantly impact the health insurer's ability to recover its costs.

- Burden on Health Insurers: This places a practical burden on NHI insurers to be aware of potential third-party liability situations, ascertain the status of any claims or payments between the victim and the tortfeasor/liability insurer, and act promptly to assert their subrogation rights if a claim balance exists when they provide benefits.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 10, 1998, judgment clarified that payments made under Japan's Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI) system directly to an injured victim extinguish the victim's overall damages claim against the tortfeasor on a yen-for-yen basis, regardless of how the CALI insurer internally allocates the funds among damage items. This extinguishment occurs chronologically as payments (including provisional payments) are made. Consequently, a National Health Insurance provider's right to subrogation under NHIA Article 64(1) only attaches to the extent that the victim's claim against the tortfeasor still exists at the moment the health benefit is provided. This ruling necessitates a careful chronological analysis when coordinating benefits between social health insurance and third-party liability payments following accidents.

Mapping the Limits of Transparency: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Preliminary Dam Site Information

Cross‑Border Data Access & Platform Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Tackles Online Obscenity Case (2021)

Indirect Victims in Japanese Tort Law: Implications for U.S. Businesses

Health Insurance Policy Information – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance Portal – Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

National Health Insurance Act (Unofficial English Translation) – Japanese Law Translation