Constitutionality of Bankruptcy Discharge in Japan: A Landmark Supreme Court Decision

Date of Decision: December 13, 1961 (Showa 36)

Case Name: Special Appeal Against Dismissal of Appeal Regarding Bankrupt's Discharge Decision

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

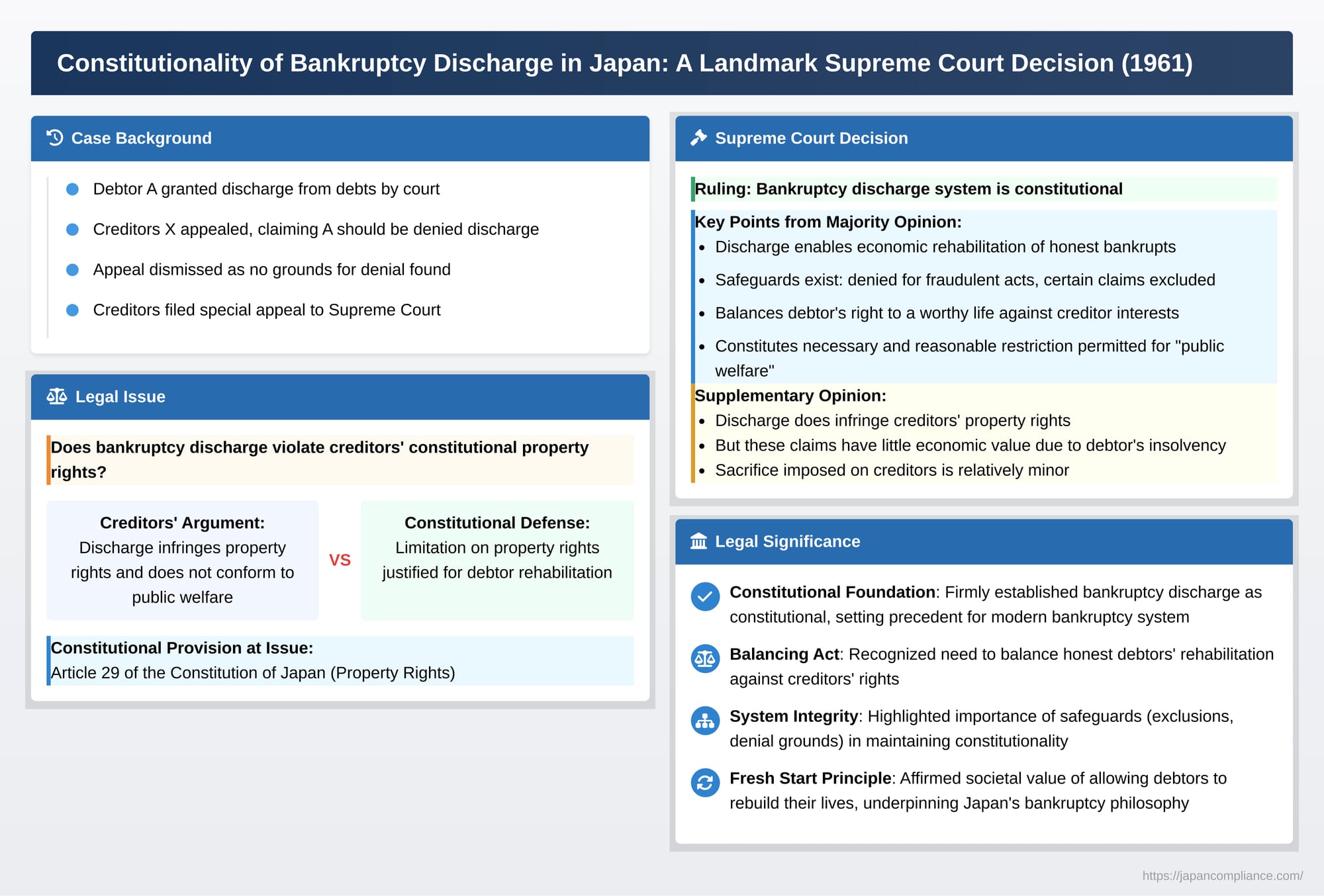

This blog post delves into a foundational 1961 decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan that addressed the constitutionality of the bankruptcy discharge system. The central question was whether releasing a debtor from their unpaid debts after bankruptcy proceedings unacceptably infringes upon creditors' property rights as guaranteed by Article 29 of the Constitution of Japan.

Facts of the Case

A debtor, A, was granted a discharge from debts by a court decision. Creditors X and others (the appellants) appealed this decision, arguing that A should not be granted discharge due to alleged grounds for denial, including breach of the duty to provide explanations, submission of a false list of creditors, and failure to prepare commercial books. Their appeal was dismissed on the basis that no grounds for denying discharge were found to exist for A.

X and the other creditors then filed a special appeal with the Supreme Court. They contended that the bankruptcy discharge system itself was unconstitutional because it infringed upon the property rights of bankruptcy creditors, did not conform to the public welfare, and lacked provisions for just compensation, thereby violating Article 29 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court's Decision (Majority Opinion)

The Supreme Court dismissed the special appeal, upholding the constitutionality of the bankruptcy discharge system .

The Court reasoned as follows:

- Purpose of Bankruptcy Discharge:

The discharge granted to a bankrupt under the Bankruptcy Act is a benefit bestowed upon an honest bankrupt. It releases them from liability for debts that could not be satisfied from the bankruptcy estate during the bankruptcy proceedings, with the exception of certain specified claims. The objective of this system is that if bankrupts were to be pursued indefinitely for their debts after the conclusion of bankruptcy proceedings, their economic rehabilitation would become exceedingly difficult, potentially leading to a complete breakdown of their lives. Therefore, to enable the rehabilitation of honest bankrupts, it is necessary to shield them from such pursuit by creditors. - Safeguards for Honesty and Reasonable Scope:

- The Bankruptcy Act (Article 366-9 of the old Act, now Article 252, Paragraph 1 of the current Act) stipulated that if the debtor committed acts constituting fraudulent or culpable bankruptcy, or other acts of bad faith listed in the article, the court could deny discharge. This indicates that discharge is intended for honest bankrupts.

- Furthermore, Article 366-12 of the old Act (now Article 253, Paragraph 1 of the current Act) excluded certain types of claims from discharge, such as taxes and employee wages, recognizing that it would be inappropriate to discharge these. This limited the discharge to other general bankruptcy claims.

- The Court viewed these provisions as reasonably regulating the scope of the discharge's effect.

- Balancing Interests and "Public Welfare":

- While it is clear that discharging a bankrupt from general bankruptcy claims is disadvantageous to creditors, the Court emphasized the necessity of rehabilitating bankrupts and guaranteeing their right to live a life worthy of a human being.

- Moreover, the Court noted that if discharge were not permitted, debtors would generally tend to conceal the deterioration of their financial situation, often leading to a worst-case scenario that could ultimately cause greater harm to creditors. Thus, discharge can also serve as a means for creditors to avoid the most severe outcomes.

- Considering these points, the Supreme Court concluded that the provisions for discharge are a necessary and reasonable restriction on property rights, permitted under the Constitution for the "public welfare". Therefore, these discharge provisions do not violate Article 29 of the Constitution.

Supplementary Opinion by Certain Justices

Several justices joined in a supplementary opinion, concurring with the majority's conclusion but offering additional perspectives on the balance of interests .

- They agreed that the discharge system exists to give honest bankrupts a chance for economic rebirth and rehabilitation .

- However, they explicitly acknowledged that discharge undoubtedly infringes upon creditors' property rights by extinguishing a portion of their claims .

- Crucial Consideration: The justices in the supplementary opinion highlighted that the claims being discharged are against a debtor who is insolvent. Therefore, at the time of discharge, these claims have little, if any, substantial economic value . Consequently, the actual sacrifice imposed on creditors is not very large .

- Basis for Reasonableness: The reasonableness of the bankruptcy discharge system, in their view, could be affirmed by impartially considering both the opportunity for the bankrupt's rehabilitation and the relatively minor nature of the sacrifice borne by the creditors .

- They cautioned that the rehabilitation of an honest bankrupt, while important, does not by itself justify imposing substantial sacrifices on creditors under the guise of public welfare . Ultimately, it is a matter of impartially weighing the interests of both sides. If the disadvantage to creditors is of this limited extent (due to the prior insolvency of the debtor), then it can be accepted as an unavoidable restriction for the sake of the public welfare .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Bankruptcy Discharge and the Constitutional Guarantee of Property Rights

- Bankruptcy proceedings are a form of collective enforcement, during which individual enforcement of claims by creditors is prohibited (Bankruptcy Act Article 100, Paragraph 1). However, discharge from debts after the proceedings conclude is not an automatic consequence. The bankruptcy discharge system was not originally part of Japan's old Bankruptcy Act but was introduced in 1952, concurrently with the enactment of the Corporate Reorganization Act (old Bankruptcy Act Article 366-2 et seq.), and has been carried over into the current law.

- A bankrupt individual can apply for discharge during a specific period, from the filing of the bankruptcy petition until one month after the bankruptcy commencement decision becomes final (Bankruptcy Act Article 248, Paragraph 1). If a discharge order becomes final, the bankrupt is released from liability for their bankruptcy claims, except for any amounts paid through dividends in the bankruptcy proceeding and certain non-dischargeable claims (Bankruptcy Act Article 253). For creditors, this means they can no longer enforce their claims against the debtor, resulting in a substantive loss of rights, regardless of whether this is viewed as an extinguishment of the debt itself or merely of the debtor's liability.

- From the creditors' perspective, bankruptcy discharge can be seen as a judicial deprivation of substantive interests, potentially infringing on their property rights protected by Article 29 of the Constitution. However, such an infringement may be deemed constitutional if it conforms to the "public welfare". The established judicial test for this involves a comparative balancing of factors, including the purpose of the regulation, its necessity, its content, the type and nature of the property right being restricted, and the extent of the restriction.

2. "Public Welfare" and the Tension Between Constitutional Values

- In the case of corporations, the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings is a cause for dissolution, and upon the conclusion of the proceedings, the corporation's legal personality ceases to exist, leading to the creditors losing their rights (Companies Act Article 471, Item 5; General Incorporated Associations and General Incorporated Foundations Act Article 202, Paragraph 1, Item 5).

- For individual debtors, however, if they could not obtain a discharge, they would face unending pursuit from creditors (unless the debts were fully paid or otherwise extinguished), potentially leading to a state of "debt slavery". From the perspective of debtor rehabilitation and ensuring a life worthy of a human being, the discharge system is indispensable.

- While it can be argued that a debtor's minimum living standards are protected by "free assets" (property exempt from the bankruptcy estate under Bankruptcy Act Article 34, Paragraph 3) and by seizure-exempt property rules in individual enforcement proceedings (Civil Execution Act Articles 131, 152; National Pension Act Article 24; Public Assistance Act Article 58, etc.), the constant threat of creditor pursuit without the prospect of discharge could crush a debtor's motivation to rebuild their life and could also negatively impact their family's right to pursue happiness.

- Leaving more assets with the debtor (expanding "free assets") would aid their rehabilitation, but this would correspondingly reduce the bankruptcy estate available for distribution to creditors, creating a direct conflict of interest. Credit, such as housing or business loans, is often extended based on the debtor's anticipated future income and assets. Creditors might argue that these future assets should be part of the bankruptcy estate, while a focus on debtor rehabilitation would suggest they should remain with the debtor as a basis for a fresh start. The Japanese Bankruptcy Act adopts the "fixed estate principle" (固定主義 - kotei-shugi, where the estate is generally fixed at the time of bankruptcy commencement), which is considered more conducive to the debtor's economic rehabilitation.

- Furthermore, if individuals cannot achieve economic rehabilitation, it could dampen entrepreneurial spirit and labor motivation, thereby affecting the broader economy. The discharge system can thus be seen as necessary for the foundation of a capitalist society and may also prevent an increase in public welfare costs.

- Discharge is a privilege granted to bankrupts. It would not be justifiable to grant discharge to those who have acted against the order of the transactional community or who have been uncooperative in the proceedings and harmed creditors' interests. For this reason, the law provides grounds for denying discharge (Bankruptcy Act Article 252, Paragraph 1), reflecting the need to limit discharge to appropriate cases. Discussions in practice around conditional or partial discharge concern the possibility and necessity of limiting the scope of discharge to achieve a balance with creditor interests.

3. The Nature and Extent of Infringed Property Rights

- In assessing constitutionality, the extent of the infringed interest is a key consideration. While discharge clearly imposes a significant disadvantage on creditors by extinguishing their claims, the substantive value of these bankruptcy claims is entirely dependent on the debtor's actual ability to pay.

- Bankruptcy proceedings are designed to liquidate all of the bankrupt's non-exempt assets, and creditors are entitled to receive dividends from these proceeds. Through participation in the bankruptcy process, creditors have the opportunity to realize the present economic value of their claims. If the system did not, even in principle, aim to realize this substantive value before granting a discharge, the discharge system could hardly be justified and would likely be unconstitutional. This point was particularly emphasized by the supplementary opinion in the 1961 case. The principle of "liquidation value guarantee" (清算価値保障原則 - seisan kachi hoshō gensoku), known in corporate reorganization law, is also relevant to the interplay between bankruptcy proceedings and discharge.

- The proper execution of bankruptcy proceedings to realize the substantive value of bankruptcy claims is therefore crucial. In consumer bankruptcies, it is not uncommon for proceedings to be closed simultaneously with their commencement due to a lack of sufficient assets to cover procedural costs (同時廃止 - dōji haishi), resulting in no distribution to creditors. This outcome, while meaning no actual payout, is generally considered an unavoidable consequence of the debtor's financial state, and the "real value" of the claims is, in a sense, deemed to have been realized (or confirmed as nil).

- The Bankruptcy Act also specifies certain categories of claims as non-dischargeable (Bankruptcy Act Article 253, Paragraph 1), which restricts the scope of the discharge order to maintain a reasonable balance between the bankrupt and creditors. While the exact scope of non-dischargeable claims is a matter of legislative policy, it must be justifiable from the perspective of public welfare.

4. Procedural Guarantees for Creditors

- If creditors could only stand by and watch their rights be extinguished, it would raise procedural due process concerns. However, bankruptcy creditors are given the opportunity to state their opinions during the discharge proceedings (Bankruptcy Act Article 251) and can file an immediate appeal against a discharge permission order (Bankruptcy Act Article 252, Paragraph 5). This allows creditors to participate in the discharge process, providing procedural safeguards.

- Furthermore, even after a discharge order becomes final, the question of whether a specific creditor's claim is actually covered by the discharge (i.e., whether it is a dischargeable debt) is a matter of substantive right and can be determined through separate litigation if disputed.

5. Summary from the Commentary

The Japanese Bankruptcy Act aims not only to liquidate the financial affairs of an economically failed debtor but also to secure an opportunity for their economic rehabilitation (Bankruptcy Act Article 1). Bankruptcy discharge is an indispensable system for achieving this latter objective. While the constitutionality of the discharge system itself is generally not in doubt, it cannot be justified solely by the need for debtor rehabilitation. Rather, the constitutionality of the discharge system is supported by the overall rationality of the entire framework, including provisions for grounds for denial of discharge, the categories of non-dischargeable claims, and procedural safeguards for creditors.

Conclusion

The 1961 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision firmly established the constitutionality of Japan's bankruptcy discharge system. It recognized discharge as a vital tool for the economic rehabilitation of honest debtors, deeming it a necessary and reasonable restriction on creditors' property rights justifiable under the "public welfare" clause of the Constitution. The decision, particularly when read with the supplementary opinion, underscores a careful balancing act: providing a fresh start for debtors while acknowledging the impact on creditors, whose claims are often of little practical value by the time of discharge due to the debtor's insolvency. This landmark ruling continues to underpin the modern Japanese bankruptcy system's dual aims of equitable liquidation and debtor rehabilitation.